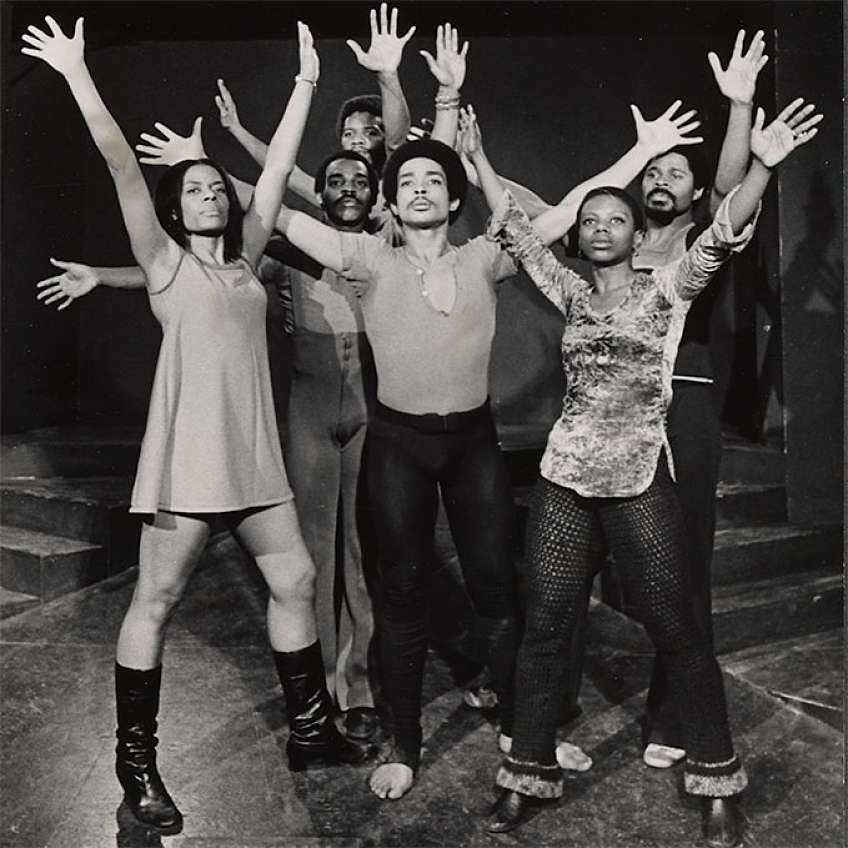

Multitalented Hope Clarke (she/her) is a rare gem in the artistic world. Over the course of her stellar five-decade career, she acquired professional credits as an acclaimed dancer, actress, choreographer, and director. She not only worked with notable directors, from Vinnette Carroll to George C. Wolfe, she also trained and danced with legendary choreographers. She directed and choreographed for the stage while also acting in film, television, and theatre.

While we kept our pandemic-mandated social distance, she was kind enough to sit down and talk with me last year about her long and diverse career.

NATHANIEL G. NESMITH: What first enthralled you about dance, and how did you get started in it?

HOPE CLARKE: I had a lot of energy. I would do the boogie-woogie to my records at 3 years old, and they decided that maybe I should go to dance classes. That is what they did. My sister and I were at the Alma Davis Dance School.

In 1959, you were a senior in high school in Washington, D.C., when your sister, who lived in New York City, sent you a newspaper announcement for an audition. Would you finish the rest of the story?

It was West Side Story, and the company was on tour. Ella Thompson was leaving—I think a couple of people were leaving, so they had to have auditions. My sister saw it in the newspaper, and she called me. She said, “Why don’t you come up and do the audition and see just what goes on in the professional world, how it happens?” I said, “Okay.” I was with Doris Jones; I was the lead dancer at that time. I came up and I did the audition and it was a good audition—and I got the job. But I had not intended to leave my dance class, because we were getting ready for our big concert. I told them, “Look, I cannot do this, I just wanted to have the experience.” And they said, “You are going to join the company.” And I said, “Oh no, you don’t understand,” and they said, “No, you don’t understand, you will be joining West Side Story.” It was in Chicago at that time. They wanted to know if I had ever flown. I said no. They said, “We’re flying you home so you can get all of your stuff and then we will fly you to Chicago to join West Side Story.” And I’m thinking: I don’t want to do this. That is how it happened.

When I arrived, Jerome Robbins was there. He was there to terrorize people, and he loved it, to clean house and whatever else. When I came to my first rehearsal, he was my first teacher, not the dance captain or anybody else. That was quite interesting. I didn’t know anything about Jerome Robbins. It was a little bit nerve-wracking having this person teach me—I think it was the cha cha. His way was different from most people in the world. When you do this dance, it is done on one-two, one-two, one-two-three-four. He did it on one. I had to get used to that. That was my beginning with West Side Story.

In 1961, Brock Peters, Robert Guillaume, and Rex Ingram were in the Broadway production of Kwamina, which did not run too long but tackled a controversial topic at the time: an interracial love story. Agnes de Mille was the choreographer, and three of the dancers in the production got my attention: Louis Johnson, Barbara Ann Teer, and you. Of course, Teer went on to become the founder of the National Black Theatre in Harlem. What was it like to work with Agnes de Mille?

Oh, it was fascinating working with her. See, I was a kid. I was only about 20 then, and I worried her to death. She did not do African dance—you know, she was Agnes de Mille. Her thing was, she could look at the stage with people and see exactly what it was supposed to be. It was wonderful to watch her work. I remember one time she was giving us notes or something, and she said, “All I see is Hope Clarke over there chewing that chewing gum.” She was very easy to get along with. You learned a lot from her. That was fun.

In the 1960s, you were a dancer with the Katherine Dunham Company and the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater. In retrospect, what did you get from working with those companies, and how did dancing with them prepare you for your future?

I got a tremendous amount from the Dunham company. Her technique was as good as anybody’s. It was difficult, but you had to just knuckle down and learn it and do it. She was very easy to get along with and she always spoke quietly, very quietly. She brought in different people from different African areas for The Blue Women, Little Haiti Girl, and The Moroccans. It was an education, to say the least, working with her.

In 1967, you were in Hallelujah, Baby! Robert Hooks was Clem; Leslie Uggams was Georgina; Lillian Hayman was Momma, and Arthur Laurents did the book. This production received nine Tony nominations and won five, including Best Musical. Louis Johnson was also a dancer in this production. It was the first Broadway musical where you were not just a dancer—you also played a maid and were part of the ensemble. What was it like working with that cast, and did you have any dealings with Arthur Laurents?

Not really. Later on, when we did it again, when he rewrote it, I did the choreography. It was not a good show. It was difficult. We didn’t really like it that much. What I liked was to watch Leslie singing those songs; Leslie can learn a song (snaps) like that. But it wasn’t a great show and it wasn’t a great story. People were not that happy with it. It was a job and we did it. I don’t remember how long it lasted.

Not long. Then in 1969, Michael Schultz directed you in Douglas Turner Ward’s The Reckoning at the St. Mark’s Playhouse. In that production, you worked with Louise Stubbs. How did this production come about, and what would you like to share about that experience?

Oh, it was a wonderful production, because Doug was in it. And it was a wonderful cast. I must tell you this about Joe Attles, who was one of the most incredible people on the planet. I think about him still. He was so caring about all of us. He would cook stews, and if you happened to be downtown and you wanted to have something to eat, you could go over to his house. He was just divine. He was in the show. He would do this on purpose (smacks her cheeks) during the show, and this one time, one by one, the actors started laughing; but Doug never broke down, never. What we had to do to get through, we turned and faced upstage. We did most of the show standing upstage until we could get ourselves together to turn around. I will never forget him, or that show.

In 1970, Ossie Davis turned his play Purlie Victorious into a Broadway musical, Purlie, which was nominated for five Tonys and also had a very talented cast: Cleavon Little, Linda Hopkins, Melba Moore, Novella Nelson, and Sherman Hemsley. The choreographer was Louis Johnson, and you were one of the dancers; so was George Faison. How difficult was it to get into that show, and what was it like to work with the legendary choreographer Louis Johnson?

I had worked with Louis over the years. This wasn’t anything new. He could be very difficult and mean sometimes. The opening number was wonderful. I think this was his first Broadway show, and they were trying to tell him, “Louis, you do not have to choreograph the entire show in one or two days.” He had three weeks, but he got that thing done in two or three days. He could be very difficult, and we had our arguments; I was in his company at one time. To this day, I don’t understand what it was all about. He was really mean, but brilliant. So what can I say?

Vinnette Carroll was the first African American woman to direct on Broadway with the 1972 production of the musical Don’t Bother Me, I Can’t Cope, for which Micki Grant wrote the music, lyrics, and book. That Broadway production received critical acclaim and had a long run. How did you become involved in the show, and what was it like to work with Carroll and Grant?

I had worked with Vinnette Carroll before with her organization, the Urban Arts Corps. And Talley Beatty worked with her a lot. In fact, Talley was the original choreographer for Don’t Bother Me, I Can’t Cope. Talley worked with her on most of the productions, and, of course, they had arguments. They loved to argue, Talley particularly.

We were in rehearsal near the beginning, and they got into it, and we all said, “Oh Lord, here we go.” He picked up his bag and walked out. Generally, she would call him back or he would come back. Vinnette was not the easiest person. “Change” was her motto: Keep changing, changing, changing, which could drive all of us crazy. So when Talley walked out, we were all saying, “What’s going to happen? ” We all assumed she would call him back, because that’s how it always was. She didn’t, and when we came to rehearsal, George Faison did the choreography. I thought he did a very good job, especially with my solo number. It was very pretty, very well done.

Anything else you want to say about Don’t Bother Me, I Can’t Cope?

I do have to say this. I can tell this now. We had a wonderful producer, Norman Kean. (He was wonderful right up to when he killed his wife and himself.) We were on Broadway at the Edison Theatre, and Norman would close the show and take us on tour to make more money. We would go to a couple of cities, then come right on back and open up the show. People would come to get their tickets while we were gone and Norman would say, “So sorry, it is sold out tonight.” We would only be gone a couple of days, not weeks—only a couple of days. We would go to places like Indianapolis. I know because Secretariat—I saw him run when we were on tour. I think Norman did that three times: Take the company on tour, then come back.

The theatre would be closed just like that?

Yes, he would take us to a couple of places, then we would come back and stay on Broadway. We made a nice little piece of change, because he was all about making money.

You acted some in films and TV, then came back to Broadway again as choreographer on Jelly’s Last Jam. Had you worked with George C. Wolfe before then?

I knew nothing about George until we did The Colored Museum. I was sitting in my house and a dancer friend of mine called and said he was at the theatre at Crossroads, and they needed a choreographer and asked me to come down. I had never choreographed nothing. I knew nothing about choreographing. But I went down to Crossroads Theatre and they were rehearsing. I sat there and they gave me the script, and I was reading it, and I said, “I want to do this show. I love this show!”

The next day they were rehearsing something, and I came in, and they wanted me to start that day. I had never done it before, but somehow or other, something came to me and I started choreographing. That’s how it happened. Frank Rich loved it; he sent for the script before he reviewed it.

You also choreographed The Colored Museum at the Public Theater, as well as doing Spunk and The Caucasian Chalk Circle there. Did you have any dealings with Joseph Papp?

Oh, my Pappy. (Becomes deeply emotional). I was down there when we used to go into the park, and they would put tables together and make a stage. That is what we used to do, and go around the city in the summertime. We all loved Pappy and he loved us. He was the one who brought The Colored Museum to his theatre, where we did it a second time. We all loved him, and he loved us.

The Caucasian Chalk Circle, which was adapted by Thulani Davis and directed by Wolfe, had an interesting cast. I would like to ask about two of the actresses, Novella Nelson and Charlayne Woodard. What was it like to work with both of them before their careers took off?

Well, we were all old friends by that time. Charlayne wasn’t as close, but she is a very good actress. And, of course, Novella, what can you say? We had no problems. George and I felt that was our crowning glory. I don’t know how he thought of all of this. Everybody had at least three or four different roles, and you could not go backstage because you could get hurt—that’s how fast things were going. So he staged how the actors would move backstage, and I did the choreography out front. It was quite wonderful. He loved that show; we all did. It was a difficult show, but I think it was one of his finest.

On Jelly’s Last Jam, you worked with an exceptional team—not just Wolfe but Susan Birkenhead on lyrics, Luther Henderson on music and orchestration, Jules Fisher on lighting, Robin Wagner on sets, Toni-Leslie James on costumes. How was it working with this team, and when did you all realize that you had something special?

On Jelly’s Last Jam, you worked with an exceptional team—not just Wolfe but Susan Birkenhead on lyrics, Luther Henderson on music and orchestration, Jules Fisher on lighting, Robin Wagner on sets, Toni-Leslie James on costumes. How was it working with this team, and when did you all realize that you had something special?

We did the first Jelly in California, which was entirely different than the one we did on Broadway. I don’t know why we had to do all those changes. I wasn’t the first choreographer; that was Otis Sallid. They were having difficulty with Otis in getting his contract together. I was in his house and he was cooking soup. He does do good soup. And he said, “Hope, you better get ready.” I said, “Get ready for what?” He said, “Because I am not doing this show.” I don’t think he wanted to work with George. George can be difficult, but with George you really got to turn it out; you have to really be on point, on your toes, with the choreography because, in fact, he thinks he is a choreographer.

So we took it to California, and I thought it was quite wonderful. George’s ideas—he has a great ability to see things. He is like Agnes; he can really see it. It was difficult—the show itself, you have so many characters. It was difficult. When we brought it to New York, it was a whole new Jelly’s Last Jam. And that became difficult, working with Gregory [Hines]. But we got through it and it got up. It really was quite wonderful.

You worked a lot in TV back in the day. Any stories from that time?

I did Hill Street Blues, and my scene was, I was getting ready to be killed. This is something funny: We were on set and they wanted me to try to cry, but the person who was playing my husband, he was a little crazy, and he was preparing for the scene. I sat there and watched him walk up and down; he kept making this sound, Hmmmmm, hmmmmm. Then he would look over at me. I thought, “Oh no, he is going to embarrass me. He is going to do something crazy.” The time came for us to do the scene, and I was so scared of what he was going to do that I couldn’t cry. I couldn’t get the tears out, but they accepted it, because they said they had not seen someone look as afraid as I did. It was a good scene.

How do you go about developing a dance routine for a musical as opposed to developing dance routines for a play?

I don’t think there is that much difference. You have to remember to work with the director. His focus is what you have to work with. It isn’t your idea. If he or she wants it so, I have to fit that, to create that. It is always the director. For a lot of dances you see on Broadway, the choreographers are just moving and lifting the dancers; they have no concept of what the director wants. That’s who you have to work with and create with. We didn’t just come in here to see you run around the stage. You are still telling the story. You are a storyteller with movement that has to coincide with the director’s ideas. That is what it is all about.

You’ve achieved success as a dancer, actress, choreographer, and director, and vocalist, which we did not have enough time to discuss. What would you say to emerging artists who want to follow in any or all of your paths—what advice would you offer them?

Work hard. Study. Work hard. That is what you have to do. You have to be on it. Dancers—take your classes. Actors—go take acting classes. You just have to stay on it. Get in it and stay on it because you never know what you are going to get if and when you get a job. You want to be able to say, “Okay, I got it.” You got to be ready all the time.

Nathaniel G. Nesmith (he/him) holds an MFA in playwriting and a Ph.D. in theatre from Columbia University.