This past summer, there was a national uprising led by Black people in response to our continued murders at the hands of the police. People called for defunding the police in order to abolish the police, for funding Black futures instead of funding our murders at the hands of the state. It was powerful. And how did the American theatre respond?

We put out statements about how we were listening and learning. We organized committees. We made demands and we issued next steps about how those demands would be met. We worked to see how we could make our institutions more antiracist.

But how is all that going to stop the police from killing Black people?

Is it that we think that’s “not our fight” and we need to focus on what is? If so, that’s where we’re wrong: It is our fight. The theatre industry is made up of human beings. Black people, who have fears of the police, and people of all races, who are worried about their friends. The American theatre is not separate from the rest of the world. We are the world!

Right now many of us are working as though we want to build more antiracist theatre institutions. And that work is valid! That’s why the two of us were given the space to write this article; we’ve been working on this issue within Baltimore Center Stage. There is space for that work. But that can’t be the final goal. We cannot have the most antiracist institutions while the police are still killing Black and Indigenous folks. We cannot have the most antiracist institutions while Black and Indigenous people live in poverty. We cannot have the most antiracist institutions while people don’t have healthcare. The theatre industry is made up of human beings who are affected by all of these problems. What sense does it make to only be working to erase biases within our institution when we know that won’t erase all the other inequities that impact us every day?

So what is to be done to change the theatre industry? That is the question. Or at least, it’s the question we were asked when first approached about writing this. But we’re not so sure that is the question we should be asking.

One of the most powerful recent shifts in our cultural landscape has been the increased dialogue around abolition of the prison industrial complex. Among many lessons that the movement for police abolition has taught us is that we are often asking the wrong questions and thinking too small. In a recent panel conversation on mutual aid, abolitionist Mariame Kaba asked, “How do you define the world you want to create, the world you want to build in, the world you want to live in?” Rather than asking what needs fixing in the theatre industry by itself, we should be following Kaba’s lead: What is the world we want to create, and how do we as theatremakers actually take steps toward that world?

We need to shift our vision. Instead of working toward a more antiracist theatre industry, we need to be working toward a liberated world.

Recognize Your Power

“Power is infinite. There is no inherent limit on the amount of power people can create.” —Eric Liu

When American Theatre initially reached out to ask Baltimore Center Stage to contribute to this series, we were not the first people they thought of. In fact, we are probably not the first ones anyone thinks of when they think of BCS. We are both fairly low in the hierarchical structure of the staff. We are early in our careers. We are young. We are Black. (We’d be remiss if we didn’t mention that we are both mixed and light-skinned, and benefit from all the associated privileges. It is not a coincidence that there are so few Black women on our staff and we are mostly light-skinned.)

When people talk about “thought leaders” in the theatre industry, in other words, they are not talking about us. But BCS doesn’t exist without the people animating it—and that includes the artists, the leadership, the production staff, the administrators, even those of us at the earliest stages of our careers. We all have so much more power than we think, and that power doesn’t come from the institutions we work for. It’s time we stop relinquishing that power and start mobilizing. There are steps each of us can take, and roles we can play, in manifesting the liberated world we want to live in.

See Yourself as a Cultural Worker

“As a culture worker who belongs to an oppressed people, my job is to make revolution irresistible” —Toni Cade Bambara

We are all here because we believe in the power of theatre, right? We think it has the power to change minds, to catalyze conversations, to shift narratives. But we most often limit that to what’s on our stages, with the goal that our mostly wealthy, mostly white patrons might see our groundbreaking show and say, “Wow, I never knew that.”

But if we approached theatremaking as cultural workers, we wouldn’t be measuring success only by the number of tickets sold, and our programming choices wouldn’t be driven primarily by the institution’s need to sustain itself. Everything we do could instead be measured by its impact on the material realities of the communities affected by the issues onstage, by its contribution to BIPOC healing and joy, and by its vision of an irresistible revolution.

As cultural workers, we don’t have to limit that work to what happens within the walls of resident theatre companies. What would happen if all the playwrights and actors at theatres in every town went to their local Black-led organization, the one that organized protests over the summer, and said, “How can we help you tell this story?” What would happen if all the arts administrators went to these same organizers and said, “How can we help you manage this work?” What would happen if we actually chose to dedicate our efforts toward serving our local communities?

There are already people doing this work. There have always been people doing this work. We need to start doing this work too.

Turn Your Attention Local

“Small is good, small is all. (The large is a reflection of the small)” —adrienne maree brown

What does it matter if people in New York City or California are talking about the work of Baltimore Center Stage, if there are folks two blocks from our theatre who don’t feel welcome in our building? Who are we doing this work for? Some things are universal, sure, but theatres in different cities with different histories and demographics cannot best serve their local communities by doing the same programs and shows.

As we move forward, we should be looking to the people in our surrounding neighborhoods and asking: What do they need? What are the organizations that are fighting for those things within our own cities? And how can we join that fight?

Over the summer, many theatres across the nation opened their lobbies for protesters. It was probably the most radical material action that any theatre took. We realized we had resources to offer (space, snacks, phone chargers, water, bathrooms), and we offered them to people who were doing the work of fighting for a liberated world. This is the kind of action that can happen when we are paying attention to our surrounding community. When we shift our vision to fighting for a liberated world instead of fighting for an antiracist theatre industry, we can go so much further.

Build Coalitions With Co-Workers…Then Do Stuff

“We are each other’s harvest; we are each other’s business; we are each other’s magnitude and bond.” —Gwendolyn Brooks

This may be a hot take but…institutions are not our friends. We’ve known this for a long time. The major theatre institutions across the country were founded on white supremacist principles, on stolen land, on the exploited labor of Black and brown folks. We spend hours and hours strategizing how to maneuver around the very structures that define our nonprofits—i.e. boards, fundraising, subscriber models—in order to shift toward anti-oppressive practices.

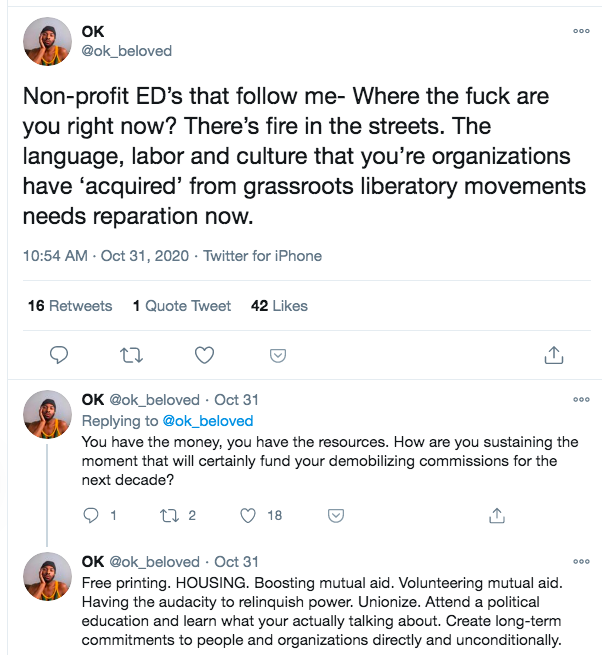

Think of all the things you’ve thought about your organization doing that couldn’t happen because of restrictions limiting the way institutions can move in the world. For instance: Nonprofits often stop short of actions that seem overtly political, because they have to remain “non-partisan” (something to complain about in another essay). Maybe there are actions that Baltimore Center Stage can’t take as an institution—but a group of employees can. We don’t need to wait for a national initiative with 50 theatres, or a program led by executive leadership of the institution. You and your coworkers can just… do the thing.

A first step is to look to your coworkers and fellow cultural workers who share your vision as people to learn and build with. Start thinking about each other as humans with the capacity to care for each other and address our needs. We are each other’s business! How can each of us leverage our resources and skills in service of each other and our art? Often this could manifest in economic support: Venmo-ing a few extra dollars so your apprentices can stock up on groceries at the beginning of the pandemic, or offering free housing for furloughed employees.

There are practices beyond monetary support as well: At BCS, some of us have organized a writing group to support the creative practices of our staff. We regularly offer restorative spaces. We create the conditions for seeing each other as people and bringing our full humanity into what we’re doing.

What doors would open up if we thought about institutions as a way to build with community rather than a physical structure? In this pandemic, it’s more clear than ever that our buildings do not define us. At its best, the theatre industry could be a network of interconnected cultural workers—that is the core of what we do and why we do it, and we need to be building up those coalitions in order to weather the coming storms. As Mariame Kaba says, “Everything worthwhile is done with other people.”

We’ve begun the work of this necessary coalition building at Baltimore Center Stage in our staff-organized Antiracism & Anti-Oppression Committee (ARAO for short). Among the key principles that guide ARAO is the notion that we do not work exclusively in service of the institution. Our work does not start and stop with Baltimore Center Stage, but instead focuses on how we can show up as better neighbors, how we can be advancing our own political education, how we can be in right relationship with one another.

ARAO looked outside our windows, saw the opioid crisis playing out right on our front steps, and planned a training with Baltimore Harm Reduction Coalition about how to care for drug users in our community. We looked among the staff, saw frustration about a lack of transparency, and organized a salary share. We looked at our community, saw a desire to learn, and built an antiracism library right in the hallway of our third floor.

The best version of ARAO’s work would look like virtuous cycles, in which the learning we do together fuels how each of us shows up in the world at large, which in turn builds knowledge and informs our culture and practices at BCS. We are lucky that we are generally met with support from BCS leadership, but our work is not contingent on their permission. You do not need your leadership to be on board for you to email some coworkers and start meeting. If your vision isn’t limited to serving the institution, it opens up expansive possibilities of claiming your own agency.

“We cannot create what we can’t imagine.” – Lucille Clifton

Abolition teaches us to think of institutions as experiments. We have tried the experiment of American theatre nonprofit institutions, in various guises, for more than half a century now, and we have not found it to be a sustainable and equitable way to support art-making. We should not only be looking behind us for answers. We need to dream forward.

The imagined borders we’ve erected between our industry and the rest of the world are keeping us from liberation by keeping our dreams in a box. The end of white supremacy isn’t impossible. The end of capitalism isn’t impossible. The end of imperialism, patriarchy, extraction…none of this is impossible. It’s not unreasonable—in fact it’s necessary—to be agitating for the biggest change we can imagine. We are not helping ourselves by assuming we won’t ever be able to affect massive systemic change that extends beyond the scope of theatre institutions.

And the best part about this is that we don’t need to do it alone. As soon as we realize that our struggle is interconnected with the protests on the streets is interconnected with prison abolition is interconnected with trans liberation is interconnected with Indigenous sovereignty (and so on), we can release ourselves from the pressure of having to solve it by ourselves. Theatre institutions don’t need to singlehandedly solve our healthcare system or gentrification or state violence. We can start by noticing the places in our industry where it feels hardest to create change, the recurring uphill battles that feel like impossible treks, and taking that as an invitation to widen our lens and join forces with others in the fight.

As Angela Davis said, “When we do this work of organizing against racism, hetero-patriarchy, capitalism—organizing to change the world—there are no guarantees, to use Stuart Hall’s phrase, that our work will have an immediate effect. But we have to do it as if it were possible.”

Taylor Leigh Lamb (she/her) is communications manager, and Sabine Decatur (she/they) is assistant to the artistic director, at Baltimore Center Stage.