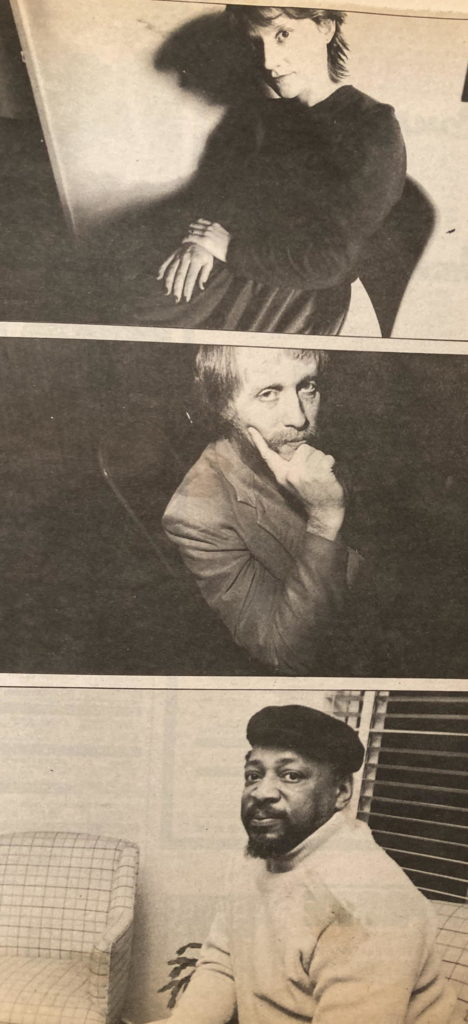

Playwright Steve Carter, a pioneering playwright of the 1970s whose plays included OneLast Look, Pecong, and the musical Shoot Me While I’m Happy, died on Sept. 15. He was 92. His colleague Anne Cattaneo spoke to him in July.

Playwright Steve Carter’s own work was chronicled in the pages of American Theatre a few years back. What is less well known about his under-sung career is the remarkable support he gave to a generation of fellow playwrights, directors, and actors in the early days of the Negro Ensemble Company as head of their Playwrights’ Workshop. The early stage work of these male and female directors of color—as well as soon-to-become-legendary actors, directors, and playwrights—has been largely forgotten, even as so many today seek to widen the repertory with diverse artists of recognized artistry and achievement.

Many of us were beginning our careers back in the 1970s, and I so vividly recall a close community of literary managers at that time, all of us juggling many jobs and meeting to passionately advocate for writers and directors we admired. A grilled cheese with bacon at Jimmy Rae’s in the theatre district and a three-hour conversation cost just $3.75—a good portion of our weekly wages. I was at the Phoenix back then; Steve was at the NEC. Steve and I have stayed in touch through the years, and I caught up with him recently in Houston, where he moved to be near his family. Thanks to his friend Debby McGee, I reconnected with him in a nursing home.

STEVE CARTER: Well, fire away.

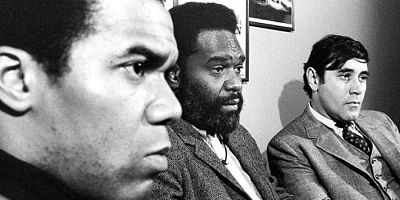

ANNE CATTANEO: Did you know Douglas Turner Ward before he created the Negro Ensemble Company? You were an aspiring playwright. What was your initial contact with the group?

Well, Doug was a playwright too, and his first plays, the one-acts Day of Absence and Happy Ending, which were largely responsible for the existence of the NEC, were actually first read at my apartment on 106th Street. But I knew Doug a long time before that, a casual relationship. We were in certain outfits together. He didn’t really know who I was or anything like that, but we were both in the Committee for the Employment of Negro Performers, which was dedicated to getting work for Black actors and other theatre folk. At first nothing came of his one-acts after that reading at my house, but then Doug finally found a producer in 1965 who wanted to do them at the St. Marks Playhouse.

I was by then a member of a group called the Fair World Theater, and one of the first productions we wanted to do were his two plays. This was before the NEC was established. I was also a member of ACT, American Community Theater, Max Glanville’s group, and we knew Doug through that group too. Finally, I was a part of Speedy Hartman’s group. It was way over on the Lower East Side at a place called the Old Reliable Theatre Tavern. It was in the back of a bar. They did a play of mine. Arthur French directed it, David Downing was in it, and Denise Nicholas, and by then they were members of the newly formed NEC. They performed One Last Look for me at the Old Reliable Theatre Tavern, and it sort of spread from there.

Where did it spread to?

The St. Mark’s Playhouse, where Doug’s one-acts were playing. Doug decided that on Monday nights the theatre would be available when it was dark, when there wasn’t anything going on there. So they would present independent productions of things on Monday night, and my One Last Look, was one of the first Monday night plays there along with a production called Black Is…We Are, a group evening which was presented by the students at the NEC. All of the students at the NEC were taking classes there for free. Doug got them everything. He even taught them martial arts and gave them classes to improve your awareness of being on the stage and your awareness of each other on the stage. We sort of carried on from there.

Say, for instance, a person like Samm-Art (Williams.) He came in to fill out an application to be in one of the classes. He was filling out an application, and he just said he wanted to work, and I saw him standing there, and he was just what the part called for in my new play Eden, a big strapping guy.

How could you miss him? He was six foot six.

(Laughs) I asked him, “Do you want to work?” and he said, “Yeah,” and I said, “You got the part!”

His Broadway successes, like his own play Home, were still to come. The St. Mark’s location was where?

Eighth Street and Second Avenue, right on the corner.

I wonder what’s there now.

As far as I remember, it is now an apartment building.

Of course. Everything’s an apartment building.

I knew that NYU took it over for a while as a residence for students, and then it changed to something else. So back then, we writers were all in the NEC’s Playwright’s Workshop, run by Lonnie Elder. I had volunteered to help Lonnie sort through all of the plays that were being sent in, but I wasn’t even on salary then. I was working for Talon Incorporated, the zipper people, and that was my regular nine-to-five job.

But you were also probably reading about 50 plays a month.

Yes. Something like that. (Laughs)

Lonnie Elder—he had a big hit with Ceremonies in Dark Old Men. And then he made a lot of money in L.A. after he wrote Sounder. He stayed out there.

He relocated to Los Angeles, and that left the Playwright’s Workshop without anybody to run it. One Saturday I went in to attend the workshop meeting, and Robert Hooks, who had founded the NEC with Doug and Gerry Krone, says, “We’re going to undergo some changes here. Steve Carter will be taking over the Playwright’s Workshop,” and Steve Carter didn’t even know what the Playwright’s Workshop was.

Wait. Who didn’t know what the Playwright’s Workshop was?

Me.

Oh, Steve Carter didn’t know what the Playwright’s… well, there you go, Steve.

Yes. (Laughs) I said, “Well, what is it?” In the end, I must admit I learned a lot more than I was ever taught. It gave me a chance to express some ideas of my own and help people here and there. I formed some very good relationships there as far as playwrights were concerned. We had people like Larry Neal and J.e. Franklin.

You said you had some ideas you contributed. What were they?

Well, for one thing, I wanted to connect with the acting students there at the NEC. Whatever would be written in the Playwright’s Workshop would be read by the acting students who could bring to life the scenes for us. Before you know it, they were taking shape and taking form on the stage, and it resulted in our first students festival, which the professional company took on their first tour to Europe. That’s when I went on salary, because Carolyn Jones said I could not work there and not make money. I had to be on salary. I had to go to the Krone-Olim office to report to Gerald Krone.

He was the managing director.

Right, and Gerry’s first words to me were, “Well, okay, Steve, we’ve seen your play, One Last Look, and it was pretty good, but what is it you have that makes you think you’re worth $35 a week to us?” (Laughs) We always joked about that after. We always joked about that.

He was a great guy. So how did the interaction work between the writers and the actors? That was a pretty damned talented group. Were there rehearsal discussions? Did you work with the writers ahead of time, reading the plays, making suggestions? Or was it just happening in the rehearsal room? What was the ambience? How did the process go?

Well, in the Saturday sessions often the playwrights doubled as actors, acting in their own stuff. A lot of times we had to explain what our words meant, because I’m not going to say everybody was on the same emotional or educational or intellectual level. We decided we would like to present a series of Monday nights with our little group, just a little thing that would last for one night, but the very next thing that happened was that it expanded to a little more than that. We created what we called a Season-Within-A-Season.

I’ve seen on the NEC website the rather large list of plays that were in those Seasons-Within-A-Season. It’s impressive.

Yes. We had so many playwrights, also some we’ve lost along the way. There was one guy I thought was a really a good playwright, but he dropped out because he was already 17 and had not made his mark and thought that time had passed for him. He killed himself.

Oh my God.

He killed himself because he thought his time would never be coming. That was the degree of fidelity that some people had about that group. Plus it was a good place to sit and talk with people who wanted to be writers or work in other jobs in the theater.

How about directors?

Well, we had Ron Mack, Ed Cambridge.

Ed Cambridge, who also later was a designer.

Lloyd Richards was there as one of the directors and…

Glenda Dickerson?

No. Glenda came in a few seasons later, but she did get to direct one thing in a Season-Within-A-Season. I think the play she directed was Judi Ann Mason’s Daughters of the Mock. I’m not sure. Maybe it was Denise Dowse.

Horacena Taylor?

Horacena really started out at the box office, she worked underneath the stairs going up to the theatre.

Wow, it sounds like Shakespeare’s company. Everybody did everything.

This was a little group. Frances Foster, she’s so well known now, but she had not directed anything until I said to her, “How would you like to direct one of the plays in the Season-Within-A-Season?” She directed my play Terraces.

So you really were the company that did everything.

Yes, yes. Later, I chose Horacena to direct my Nevis Mountain Dew when it opened down there.

You were presenting plays by Femi Euba alongside Wole Woyinka and a number of other African writers, and a slew of artists from Philadelphia: Charles Fuller, Bill Gunn, Larry Neal, Clay Goss, Walter Dallas. Along with David Rabe and Albert Innaurato, it was quite a scene there back then. Today Colman Domingo is keeping the Philadelphia sound alive, and new writers like James Ijames.

I never worked with Bill Gunn, but I certainly knew who he was. Yes, he lived in Philadelphia. He was such a good writer. But he was going more for the movies at the time I was there. He was more cinematically inclined. All that was during the most happy time of the NEC. It was at the beginning, and there was excitement around about what you were going to do. The girls were pretty and everything was going so well. Even the food at Orchidia was marvelous, and we were able to eat their famous so-called garbage pizza at the Orchidia. What wonderful days, wonderful days.

When did you move uptown? Because I’m looking at the list here on the site of the NEC, and the Season-Within-A-Season keeps going to 1975, 1976, and the next year it included Charles Fuller’s The Brownsville Raid and I think even the great Adolph Caesar wrote a play. But wasn’t that when you were still downtown?

Yes. Caesar wrote a play called The Yellow Pillow, and it was done in the Season-Within-A-Season. I left the NEC to spread my wings in 1981 and went to Chicago to accept an offer to work with Victory Gardens Theater, so the NEC actually prepared me to go out into the world.

When did the NEC end up at the church on 54th Street? Were you gone by then?

Theatre Four. Yes, I was in Chicago by then. We had to go up there—actually it was more or less dictated by the National Endowment for the Arts, because we kept putting in for grants, and they said unless we made a major move to make a little more money on our own, there would be no point in always funding us to stay where we were. I went back in 1986 just for one season, for a play that I wrote called House of Shadows, directed by Clinton Turner Davis.

After you left St. Mark’s, did you still have that same sense of a collective community—the actors running the box office, the directors sitting outside talking, you reading the plays, in rehearsals everyone jumping in and acting?

We got a little too sophisticated for our own needs. We had to sort of scale back a little bit, and by leaving the St. Mark’s Playhouse, we actually lost a lot of things. For instance, we lost our shop. We could no longer make our own sets when we went up to Theatre Four. We lost the feeling of family that we had down at St. Mark’s Playhouse, because it was like a little community. We were trying to hold on to the family feeling. But we kind of lost it. We had to scale back because we were about to lose what NEC was standing for.

I understand. That often happens. When you describe who you all were down at St. Mark’s, it has the feel of the timeless, traditional structure of a theatre company where everybody does everything. Somebody writes the play. Somebody acts in the play. Somebody runs the box office. Somebody sweeps up. But how did you get such talented people? (Laughs) I mean, it’s a legendary group of writers, a legendary company of actors, a legendary group of directors. How did that happen?

They just came in. We were all in smaller groups back then. We were in Max Glanville’s group of actors, as I said before, up at various churches around Harlem, and it sort of carried on from there. We had been doing things that people hadn’t heard of for a long time. We were going places. There was a church at 145th Street and St. Nicholas Avenue we worked in. Nobody ever heard of that church, but there was a lot of good drama going on on Saturday mornings. We were doing classes there, and I remember us doing Antigone, which we always pronounced as “Auntie Gone.” (Laughs) We did a whole lot of plays that we had no business doing. We were not promoting necessarily Black theatre. We didn’t know what Black theatre was when we were in those little churches and whatnot, but we grew out of them and started seeking better things for ourselves.

Well, I remember finding it interesting that Michael Schultz’s first play as a director with the NEC was a German play.

Song of the Lusitanian Bogey.

By Peter Weiss.

It was thrown on the desk, and basically what happened was, Michael asked Doug Ward, “Can I direct this?” and Doug said yes. (Laughs) It’s as simple as that. So it opened his career. It was the first play we ever did, and we not only carried it to Europe, but it went to California with us. It went to London. It went to Italy, and it put us on the map.

And then Michael went to California and made Car Wash and a couple of other films with Richard Pryor. Everyone thinks Spike Lee was the first Black director in Hollywood! Michael also did a Sam Shepard play, Operation Sidewinder, in the Beaumont, and Ron Milner’s What the Wine-Sellers Buy there too.

He was another one who went West.

Speaking of your peers who ended up out there, how did you cast the plays? I mean, how on earth did you choose among Giancarlo Esposito, Frances Foster, Denzel Washington…

Auditions.

Oh, you actually had…your friends had to come in and read?

Oh, yes. People came in to read, and word spread here and there. As I said, I had worked with Arthur French and David Downing. I had worked with them on theatre in the streets. We did that during one summer and then, lo and behold, they were auditioning for the Negro Ensemble Company. They made the company, and the next thing they were in Song of the Lusitanian Bogey. And then we did a summer thing where we would travel to all the boroughs of New York City. Michael directed Goldoni’s The Servant of Two Masters, and, oh, I’m trying to think—wait—we also did Chekhov’s one-act The Marriage Proposal.

Who else directed that summer?

Phoebe. Morris Carnovsky’s wife. Phoebe Brand.

Wow.

Yes. Phoebe Brand and Mart Crowley, who later wrote The Boys in the Band.

How did you find Adolph Caesar or Sam Jackson? They just came in off the street? They just heard of you?

Adolph Caesar was an old friend of Doug’s. He had a play called The Yellow Pillow, and we presented that as part of the Season-Within-A-Season. We just did it. It was one of the many plays that came across Doug’s desk. It was the most fabulous desk in town.

That’s going to be the title of this interview, Steve: “The Most Fabulous Desk in Town.” (Laughs) You were probably in very good shape from carrying manuscripts in your bag all the way from St. Mark’s Place back uptown to your apartment.

Oh, yes, and when you stop to think, I was really only down there as a volunteer to straighten out the plays that came across the desk and put them in alphabetical order. I would fire them upstairs to Doug to read, and Doug read them. I think Michael Schultz read some and whatnot. We had a lot of people. There was a woman we worked with—I don’t know what became of her—a woman named Cheryl Greene, a wonderful play reader, and she read a lot of the plays. One day she said to me, “Steve, here’s a play. We’ve got to read this. We’ve got to read this and fire this upstairs to Doug,” and it was just a little something called The River Niger.

Oh my God. She found The River Niger.

Yes. She first read it and she found it, and that’s not all she found. She found other plays. She led us to The Brownsville Raid. Reading led to everything, just reading. You just had to look for things that were on the desk.

It’s a wonderful feeling to come across something that seems really interesting and that you love, and then you quickly find other artists who share your enthusiasm. That’s how things happen.

Well, to illustrate this, one of the stories that I like to tell is about my own play, Pecong. One day many years later I was in Chicago, and the phone rang, and of all persons it was Douglas Turner Ward, and he says, “Steve, this is Doug, and I’m just calling to tell that you I think your play, Pecong, is one of the finest plays you’ve written.” Well, Graham Brown had made sure that Doug read it. He went into Doug’s office and put it where it could be seen on his desk.

(Laughs) That’s why actors were invented!

Yes. So Doug read it, and liked it and took an interest in it. I was sorry he never got to direct it, and I’ve had happiness with it and had disappointments with it too. But the fact that Doug would actually call me to tell me that he liked it was a big thrill for me. Thanks to Graham, it was there on the desk. It was buried with all the other plays on the desk, but at least it was there, and it got noticed and it got done.

Okay, Steve, I think you’ve given me one of the best interviews I’ve ever done. Everyone knows your plays, but I wanted to interview you about your other side. The side that nurtured so many others.

All right, my love. Good talking to you, Anne. You take care now.

Bye.

Anne Cattaneo is the dramaturg of Lincoln Center Theater, co-executive editor of the Lincoln Center Theater Review and creator and head of the Tony-nominated Lincoln Center Theater Directors’ Lab.