Actor, playwright, producer, and activist Vinie Burrows, 95, has been productive in theatre for more than seven decades. Burrows, who has performed and worked with many legendary artists in theatre, recently received an Obie Lifetime Achievement Award. I had the pleasure of talking with her shortly after she received it.

NATHANIEL G. NESMITH: You started your career as a child actress on a radio show. What do you remember about that experience?

VINIE BURROWS: Well, it was an exciting experience and a really meaningful experience, because I learned how to read a script quickly, extract its meanings so that it could easily be understood and comprehended. And that, of course, is a great gift for an actor, particularly when you have to audition and you are given material and have to make a favorable impression with your reading. Certainly, I think my ability to be able to give a cold reading with some rhythm, some variety, and most of all some comprehension is the gift I learned very early in radio.

Who were your early role models as an actor?

Now, that I find a difficult question. Certainly, I was influenced, as an actor, by actors I performed with in my first experience professionally on Broadway. You learn a great deal by watching what the professionals do night after night. So you could say my first mentors were Helen Hayes, as well as Georgia Burke and Alonzo Bosan, two Black actors that had been very active in theatre and on Broadway. I think working with seasoned professionals, you understand the importance of doing it every night and giving audiences a particular impression. That is a technique you have to learn by doing it. I learned by watching how Helen Hayes, Georgia Burke, Kent Smith, and some of the other actors who were seasoned professionals did it every night, no matter what was going on, or no matter what they were feeling. There were certain marks that they made always, without fail.

You were born in Harlem Hospital and graduated from Wadleigh High School. Do you think that being a New Yorker played a role in your career?

I suppose you can say that. If you are in New York, you are where it is happening, but I had not thought of it. It wouldn’t have happened if I was in Boise, Idaho. I was in high school and someone said, “They are looking for a 15-year-old girl for a Broadway show. Why don’t you audition?” and I did. That happened to be The Wisteria Trees. There were more than 100 girls who auditioned, and three months later, I learned that I got the role.

That was 1950, in a play based on Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard, directed by Joshua Logan, and starring Helen Hayes. What was that experience like?

It was thrilling, really thrilling; and because I was young, everybody was kind to me. That’s what I remember most, the kindness of the actors—all of them.

What exactly do you remember about Helen Hayes in that performance?

I watched her every night, every performance, even matinee performances, and she was a matinee star. There was one particular scene where she was always brilliant, but one evening after the show, she left the stage and said, “Damn if I wasn’t good!” I had watched her all the time do that scene, and in my opinion, that was the first time she failed. I said to myself: The performer never actually knows what he or she has done, because she thought she was brilliant and I, who had watched it, eager for that scene, thought that she was less than grand.

The 1961 Off-Off Broadway production of Jean Genet’s The Blacks ran for over 1,000 performances, featuring a wide variety of Black actors at various times—Cicely Tyson, Arthur French, Maya Angelou, Roscoe Lee Browne, Godfrey Cambridge, James Earl Jones, Raymond St. Jacques. You were in a cast with Moses Gunn, Louise Stubbs, Lex Monson, Charles Gordone, Clebert Ford, and Louis Gossett Jr., among others. Did any of you every meet Jean Genet?

No, I don’t think he ever came to New York City. He was an outsider. I think that was one of the reasons he thought that he could write a play about Blacks, highly symbolic as the outsider, because that is what Genet was, an outsider.

What was the significance of the play at the time?

Well, I touched base with many who became quite famous, that is one thing. It was a two-year show and I had to stand on a ramp. It was an Off-Broadway play—the money, I can’t remember what it was. My babysitter—my little boy was two years old—I think made more money than I did, and I said, “I will never work so hard for anybody unless I am working for myself.” That really was my first glimmer of the idea to have my own one-woman show, to be my own producer.

In the 1960s, your one-woman show Sister! Sister! explored the trials and triumphs of women all around the world. A collage of poetry, prose, and songs, borrowing from authors such as Bertolt Brecht, Sean O’Casey, and James Baldwin, it was a show you created, produced, directed, and acted in. How did that show come about?

It happened at a time when the world itself was looking at the status and conditions of women. For the first time, governments were wanting to know who they were as girls, what were the indignities and problems they faced, because the problems of the girl child became the problem of the woman. We had to look at the girl child: Is she being educated? Is she being forced into marriage at 12 years of age, 15 years, 17 years? Is she being forced to be multi-wife to men? Those were questions that were burning, because we were thinking about women for the first time as separate from men, with different experiences and certainly different inequalities.

This is what Clive Barnes of The New York Times wrote about you in 1968: “Miss Burrows is Black, good, and angry. She wounds and hurts, giving some of Black America’s most excoriating literature the whiplash impetus of a relentless performance. Yet while angry, she is not bitter. She is all woman and all fundamental charm. She is a magnificent performer.” How did that resonate with you?

It put me in another tax bracket. I remember being in Algiers at a festival. Why was someone in Algiers talking about me? He knew me because he had read the Times article about me. The Times review can put you in another tax bracket, even today.

In 1955, you were in a revival of The Skin of Our Teeth directed by Alan Schneider, who went on to have an exceptional career, including directing Beckett and Albee. What was your experience working with him?

I loved it and I loved him. He was the first director to recognize my unique talent.

What are some of the major differences when you work with a director as opposed to when you are directing yourself in something that you created?

I listen to my directors and I take directions from my directors. Myself? I am the director. The audience is the one who tells me whether I am right or wrong.

You did many one-woman shows and you brought them to many different countries, from Norway to Vietnam. How receptive were audiences in these different countries?

I was in Sapporo (Japan), and afterward a young woman came up to me—I think I was at the university there—and she said, “When I saw you, I said, ‘What has this Black woman with her braids got to do with me?’” And she said, “When the program was over, I realized you’re my sister.”

Perseverance is a key factor in establishing and maintaining an artistic career…

Is it?

I think so. How have you managed to keep your career going for so long?

Good health. And I have a life other than the theatre. I was thinking of this article that someone wrote maybe two years ago, where I am talking about the biggest role that we have in life is the role that we play in life—that is the biggest role and the most important.

You have not only been an actor but an activist. You served as vice president for Women for Racial and Economic Equality (WREE). What did this organization do, and what were some of its accomplishments?

Well, I guess it was 1977, when the United Nations had the first world conference on women, in Mexico City. I wanted to go but I couldn’t; I really didn’t have the money to go. Both children were in school and it was near the end of their term and I did not feel it was important to leave them at that critical juncture. I did not go to Mexico City, but later that year they had another world conference, still under the auspices of the UN, and that was held in East Berlin. And because the organizers wanted a diverse UN group I was chosen: I was a woman, I was a mother, and I was a working actor. As a woman of color, I qualified on all those accounts.

What was your role or association with the Women’s International Democratic Federation?

They organized the event in East Berlin that was supposed to be a counter event to the one in Mexico City. The conference in Berlin had many other women from the liberation movement in Africa, and I met Angolan women, Mozambican women, South African women, and Namibian women. It was a conference of talk not only about sexism but also about racism, which is not something I heard in the United States with white women, who were talking about getting into the boardrooms of major corporations. They were not talking about the specific disabilities of poor women and women of color and immigrant women; they were not talking about the immigrant women at that time; there was no talk about women of color.

You’ve worked with a wide variety of actors. Is there a story about an actor you think would be a good lesson for emerging theatre artists?

Though I never worked with Paul Robeson, I think his emphasis on the role that we play as citizens of the world is very important, and really more important than our role as an actor.

It is interesting that you mentioned Paul Robeson, because many Civil Rights and arts groups have honored you for promoting human rights and diversity through your artistic gifts. Artists often say, “I wish I could have done more.” What more do you wish you would have done?

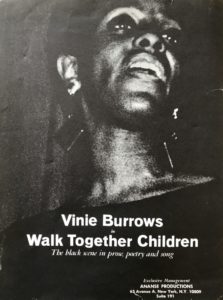

As a mother of children, as a Black mother of a Black son, I also feel as if I should have done more. I remember when I first did Walk Together Children, I got death threats and I had to take my name off the bell where I lived.

You have had a long and exceptional career in the theatre, and you have received many awards. Now you’ve received the Obie Lifetime Achievement award. How would you sum up all of this?

Better late than never; better still, never late. Why didn’t I get it at 75 or when I was at the height? Why not 34, 44, 54, 65, 74, or 84? I think they are late. But it is an honor from my peers, and I respect that because I respect their opinions.

What is the essence of Vinie Burrows that you want people to know and always remember?

Her passion for the truth and justice. That’s it.