Let’s agree that Sam Shepard was a pain in the ass. Don’t take my word for it. “I was a belligerent asshole back then,” Sam once told me. “Really,” he continued, giving me a glacier-blue stare. “I mean I was really not a pleasant person to be around.”

Wynn Handman wasn’t fazed. He had the first full-length play by the enfant terrible of the East Village, and it would launch the third season of the American Place Theatre come hell or high water—a description that’s apt for La Turista, which featured, among other offenses, the ritual slaughter of a live chicken onstage each night.

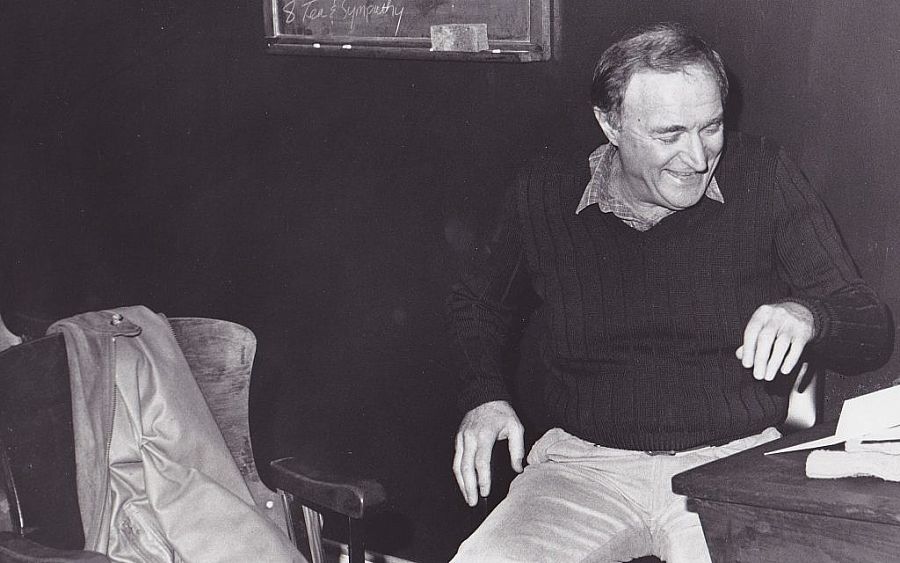

Unfazed even when Shepard came in during tech rehearsals, declaring that what had been up to that moment a three-act play was now a two-acter. “I said, ‘Listen, man, it’s too long, let’s make it a two-act play,’” Shepard recalled. “He didn’t even blink an eye. He just said, ‘Fine, whatever works.’”

Unfazed even when the defenders of fowl rights protested with exclamation-pointed letters of protest and canceled subscriptions. Even when Shepard had long since moved on to greener pastures, Handman continued to produce memorable works by him: Seduced, in which Rip Torn clomped about the stage wearing Kleenex boxes for shoes in Sam’s riff on Howard Hughes; the anti-war States of Shock, with Shepard and John Malkovich squaring off in feral opposition.

Well, I was never a Broadway baby, and these gauntlets were not entirely strange to me. Most of my formative theatregoing experiences were downtown, at La MaMa E.T.C., Judson Poets Theater, the Public, and what was then the Theatre de Lys. In the late ’60s, however, I began including St. Clement’s Protestant Episcopal Church, on far West 46th Street, in my rounds. There Handman was épatering le bourgeoisie in a makeshift theatre barely beyond Broadway’s perimeter.

His accomplices were the actor Michael Tolan and Sidney Lanier, a cousin of Tennessee Williams whose tenure at tony St. Thomas’s on Fifth Avenue was possibly made shaky by some skirt-chasing tendencies. Nursing a serious theatre jones, Lanier planned his escape by convincing the Diocese to donate St. Clement’s to the American Place in exchange for continuing to offer religious services during the day. Seed money came from the Ford and Rockefeller foundations, Ford’s Mac Lowry in particular making an enormous investment in decentralizing the Broadway-centric American theatre.

Handman and his wife Bobbie were fellow travelers in liberal Democratic circles that included Myrna Loy, Leonard and Felicia Bernstein, Adolph Green and Phyllis Newman, and Joanne Woodward and Paul Newman, along with the literary crowd that had just started the New York Review of Books. In 1964, The American Place made its debut at St. Clement’s with American poet laureate Robert Lowell’s first play, The Old Glory, which was blissfully championed in the pages of the Review by Lowell’s wife, NYRB co-founder and critic Elizabeth Hardwick.

Colorful as all this may sound, it was Wynn’s seriousness of purpose that drew my admiration and later inspired our long friendship. He would read his budding manifesto to Tolan, pencil-written in longhand on a yellow legal pad: “There is a plethora of entertainment. While they are rolling down the hill, Americans are entertaining themselves to death. Movies, TV, Ball Games, stupid records, bowling etc. and BROADWAY.” The enemy.

His mantra belonged to Gertrude Stein: “If anything is done and something is done, then somebody has to do it. Or somebody has to have done it.” And his theatre’s name was a conscious tribute to Alfred Stieglitz, whose photo gallery on Madison Avenue was called An American Place.

The roster of writers, actors, directors, and designers who benefited from Wynn Handman’s unwavering support extends to the highest ranks of those professions. The caliber of occasion did not go unrecognized: Beginning with The Old Glory, the American Place won Best Play Obies in four of its first five seasons.

One early supporter was All in the Family writer and producer Norman Lear. “I was a close viewer of the work,” he told me in a telephone conversation this week. Murder most fowl and Black Power salutes didn’t faze him, either: “Wynn and I were on the same page, so I understood and wasn’t pissed off.”

Boaty Boatwright, Handman’s friend and veteran ICM agent, recalls that one of things that attracted Shepard to the American Place was its indifference to critics. The company’s innovations included subscriptions and, at first, no single ticket sales: You had to sign on for the whole ride.

“What Sam loved most about Wynn, what hooked him,” Boatwright told me, “was the fact that Wynn said he didn’t need critics.” Some critics returned the compliment with scathing notices. Others got the message.

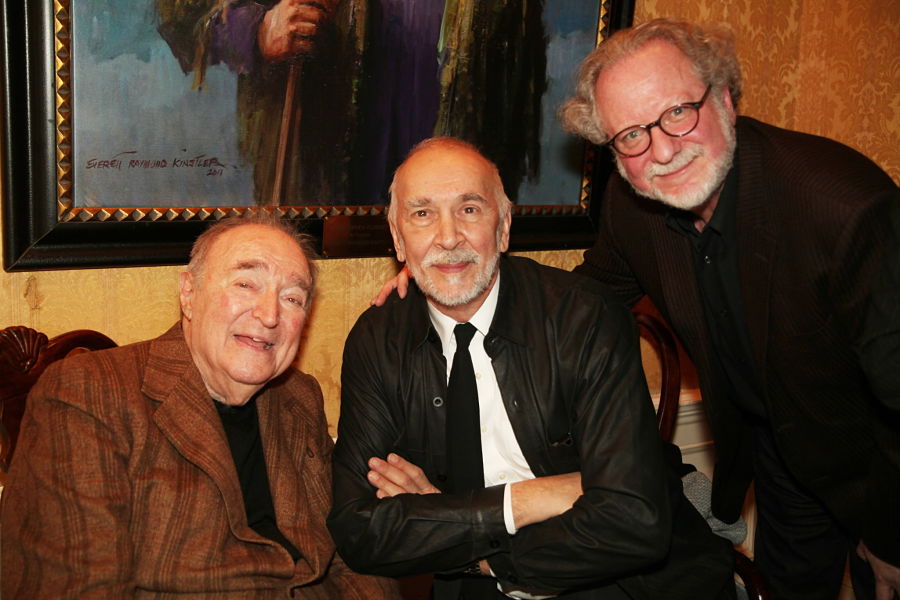

“Wynn believed in me as a critic before I believed in myself,” John Lahr wrote me this week in an email. Before distinguished tours as drama critic at the Village Voice and The New Yorker, Lahr began reviewing the American Place while at a giveaway paper called Manhattan East. “He fought for a more eloquent theatre and a more eloquent criticism,” Lahr wrote. “His passion was infectious. As an artistic director and teacher his view of the importance of theatre and intellectual debate was crucial to the American postwar theatrical scene.”

And I haven’t even broached the subject of Wynn’s teaching. His legion of students is cult-worthy. Their devotion is not only to the teacher but to the kind of man he was: a model of respect and a perfervid sharer of wisdom teased, seduced, or bled from scripts.

“For Wynn there was no separation between actor and ‘character,’” Lincoln Center Theater head and former Handman student André Bishop recalls, “because everything came from the text. An important lesson for a then young man to learn.”

The astonishing list of writer/actors produced by the APT includes Eric Bogosian, John Leguizamo, Aasif Mandvi, Cynthia Heimel, and Calvin Trillin.

“Wynn was the first acting mentor I actually listened to,” Bogosian writes in an email. “He taught me how to find all of a role, to think deeply about the character’s background. Wynn was an enthusiast, always excited by the progress of his students. He directed my first ‘hit’ in 1986, Drinking in America. In brief: This man changed my life.”

Handman compelled his students to dig deep through character work. “Wynn coaxed me into being myself,” Leguizamo wrote in an email, “and into putting up my first one-man show, Mambo Mouth.”

What else? Wynn had an encyclopedic knowledge of popular music, boasting that his cousin Lou Handman had composed the 1933 Rudy Vallée hit “Puddin’ Head Jones.” He loved nothing more than sitting at the piano and leading singalongs of lefty folk songs. He could recite long, obscure Shakespeare passages without breaking a sweat. And what Sam Shepard remembered most, he’d told me long ago, was Wynn’s “extraordinary kindness.”

Above all, Wynn Handman was humble in a way that could break your heart. His aversion to commercialism extended all too well to himself: He was lousy at the art of self-promotion. As a student I would read countless tomes about the history of Off-Broadway and the nonprofit theatre, and see passing mention, at best, of the American Place. So when he asked me to write a book about his life and work, I felt I’d been given the chance to set the record straight, and I grabbed it.

Something about his seriousness of purpose appealed to me. But more important, something powerful, ineffable connected me to him and to the artists he devoted his life to. It occurs to me that Wynn shared a crucial quality with Bernie Sanders: It was impossible not to admire his passion for remaining true to a vision articulated over half a century earlier. In Wynn’s case, it was a belief that making theatre, like living life, is a sacred gift, and we must try, with unwavering seriousness of purpose, to honor that. Whatever the odds.

Jeremy Gerard is a drama critic and cultural journalist. His book Wynn Place Show: A Biased History of the Rollicking Life & Extreme Times of Wynn Handman and The American Place Theatre is published by Smith and Kraus and is available from Amazon.