Marshall W. Mason was my teacher. By the time I studied with him, he had scaled the highest heights of the American theatre, taking his storied collaboration with Lanford Wilson from downtown’s Caffé Cino to multiple productions on Broadway. For three years, I took every class I could with him and scrawled down everything he said on legal pads and in notebooks.

Marshall W. Mason was my teacher. By the time I studied with him, he had scaled the highest heights of the American theatre, taking his storied collaboration with Lanford Wilson from downtown’s Caffé Cino to multiple productions on Broadway. For three years, I took every class I could with him and scrawled down everything he said on legal pads and in notebooks.

Marshall believed that acting was a creative art, not just an interpretive one, and that only the individual actor could inform and thrill the audience. He loved all kinds of plays—he considered himself a “small-c catholic about the theatre”—but he had been trained in the classics and could be withering about work that didn’t meet his high standards, which were those of Chekhov and Shakespeare. But Lanford—Lance to his friends and collaborators—also loved actors and their creative process, and helped Marshall realize their talents could be directed toward living playwrights, who reflected their time and deserved the attention of their generation’s best theatrical minds. The institution they formed together, Circle Repertory Company, brought together a group of highly trained actors who would create roles in the work of Circle Rep’s resident writers.

It was an extraordinary period in the American theatre—The New York Times’ Mel Gussow called Circle Rep “the chief provider of new American plays,” by Wilson, Tennessee Williams, A.R. Gurney, Mark Medoff, Sam Shepard (an old friend from the Caffé Cino days), and more, performed by an ensemble that featured Jeff Daniels, Christopher Reeve, Swoosie Kurtz, William Hurt, and many others. As Marshall’s student, I learned that creating a permanent ensemble of actors dedicated to creating roles in new plays and writers eager to write for them remained his proudest achievement in a storied career.

When I moved to New York to make my way as a stage director, I imagined myself bringing writers and actors together in a similar way. While Circle Rep was history, the tradition of actors and writers making work together lived on in the U.S. through ensembles like Steppenwolf. But New York had changed, primarily in its cost of living. The days Patti Smith wrote about in Just Kids, in which she could work 20 hours as a bookseller and save the rest of the week for creative pursuits, were long gone, and making rent required at least one full-time job. A New York premiere of a play represented a critical moment in a playwright’s career, so writers and their representatives were understandably reluctant to limit a play’s potential by declaring certain actors required for a production; likewise, actors were too busy hustling for rent to keep working on the same plays indefinitely, especially since they expected to be dropped from the project at the slightest whiff of celebrity.

I wondered if the artistic theatre that Marshall aspired to—inspired by his mentor, Alvina Krause—was destined to remain a relic of another time.

During this time, I first found my way to the 24 Hour Plays, where I am now the artistic director. At the time I was a young director thrilled to see work I’d staged performed later that night. The 24 Hour Plays were created in 1995 by Tina Fallon (who became another important mentor), as a way to bring artists together to produce work that was written, rehearsed, and performed in 24 hours. When I first worked with them in 2003, they had recently hit their stride with a series of high-profile charity events. The new play I staged by Stephen Adly Guirgis featured the actor Craig “muMs” Grant interrupting the play’s action to say, “Right now we’re dropping mad bombs over Baghdad,” 12 days into the terrible U.S. attack on Iraq.

This theatre was wasn’t just about what was happening in the world; it was happening simultaneously with the world. I was hooked.

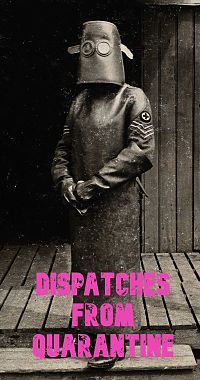

This past month, as the pandemic has necessitated an extensive shutdown, the 24 Hour Plays launched an initiative to remotely pair writers and actors who are social distancing across the world to write, film, and publish performances of new monologues in a 24-hour period. As the creators of the 24 Hour Plays and Musicals, this quick adaptation was a way to extend the artistic practice we’ve developed and produced for 25 years, on and Off-Broadway and around the world. Not only has it been a privilege to make work during this time, it’s also revealed the core strength of the 24 Hour Plays concept: the creative relationship between the writer and the actor. For our shows, actors show up and share what they can do with our writers—not only their special skills but their creative desires. Rather than the traditional formulation, where writers—and directors like me—proclaim to the actor, “Here’s what we’re looking for, can you do that?,” this approach asks the actor to declare to the writer, “Here’s what I can do and here’s what I dream of doing—what can you do with that?”

In a conversation with Tina recently, she told me that for 25 years, she believed that the central importance of the 24 Hour Plays was that they were performed live. Indeed, I hope you have the chance to see them in person some time soon, because they are indeed live, with an anything-might-happen

The 24 Hour Plays: Viral Monologues have attracted wide attention, for which our small organization is enormously grateful. But the most meaningful part for me has been to bear witness to the relationships among artists. Monday night, an actor submits their introduction video, which we share with a writer; the next morning, we send the actor a piece written expressly for them, often accompanied by a note from the writer about what a fan they are of the actor and what a privilege it was to write something short for them to perform. That night, after the piece is performed and filmed, the actor often sends back a message to the writer saying what an honor it was to speak their words. At this writing, we have done this 81 times, with no end to our isolation in sight.

I have been a theatre director for my entire adult life, so it is an ironic pleasure to find success by presenting new plays entirely staged (and filmed) by the actors who performed them. But this, too, is a credit to Marshall, one of the finest stage directors in our history, who believed that facilitating an organic collaboration between the creative instincts of the actor and the words of the play would produce results unmatched by a prescriptive approach from anyone, including the director.

People have been interviewing me now about how technology will change the theatre, which is amusing. Although I’m extremely online for a person in his 40s, I don’t claim any special prescience in this area. In this moment, to quote Sheila Heti, “I made what I could with what I had.” What I had was a career’s worth of knowledge about writers and actors, a gem of an idea from my friend Howard Sherman that filmed monologues were something artists might do in their sudden solitude, and most critically, the artistic process of the 24 Hour Plays and the small organizational platform we’ve developed to support it. That has proven to be enough, for now, to meet this moment in a way that seems to be making a difference.

I’m not one to give advice these days—I don’t even agree with myself half the time. But I do hope this moment provides an opportunity to reflect on the centrality of the relationship between the writer and the actor to the dramatic form, and to explore whether existing barriers to their direct collaboration, whether artistic or professional, are truly necessary. Perhaps, after the crisis, we might remake our institutions so that the writer and the actor can hear one another’s voices anew.

I love you, Marshall. Our work continues—it’s now streaming on Instagram TV.

Mark Armstrong is the artistic director of the 24 Hour Plays.