So far 2020 has not turned out to be the theatre year anyone anticipated. By mid-March theatres across the United States had closed their doors, canceled the remainder of their seasons, and in most cases announced layoffs and furloughs, all thanks to mandates for social distancing to stem the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. Theatre historians writing about the age of the novel coronavirus will recall seasons that never were, shows that never opened, and productions closed mid-run.

This isn’t the first time U.S. theatres have shuttered in response to catastrophe, of course. In New York City after 9/11 theatres of all sizes struggled to recover, though most above 14th Street reopened within days of the attacks. To find a national event to equal COVID-19’s impact, both on theatre and society at large, you need to look back more than a century, to 1918, to that year’s global flu pandemic.

In the first few months of that year, influenza seemed to be having an impact only on World War I-era soldiers, and the nation accordingly saw it as a matter for the War Department. But as U.S. soldiers moved around the country, and then the world, so did the disease. Despite its contemporary name, the Spanish flu, historians and epidemiologists now largely agree that it started in Kansas. It got nicknamed the Spanish flu because Spain, as a neutral country in WWI, had no wartime press censorship, so when their king fell ill it was widely reported. For many across the world it was the first time people saw it in the news, and the mistaken idea that the pandemic originated in Spain stuck.

Early U.S. reactions to the pandemic ranged from skepticism to denial, especially as it did not seem uniquely lethal throughout the spring and summer. Men continued to be drafted, troops were shipped to Europe, and life continued as usual in the cities. In fact, large gatherings were seen as good for wartime morale.

Even when evidence mounted by September that this flu was altogether worse than anyone had seen before, wartime needs still took precedence. Philadelphia’s mayor was not unusual in his refusal to cancel a massive Liberty Loan Parade, nor were newspapers that declined to warn people that huge crowds could hasten the transmission of disease. The nation had tunnel vision for the war effort.

But six weeks after that Philadelphia parade, 12,000 Philadelphians were dead from influenza. October 1918 would be the most lethal month. Deaths were so fast and frequent that hospitals could not treat all that were ill, funeral homes ran out of coffins, and there was no one to dig graves. In just 10 months, 670,000 people died in the U.S. Worldwide fatalities were between 50 and 100 million. By early 1919, this strain of influenza began to ebb, as those it had not killed managed to develop immunity. That summer it disappeared.

The history of COVID-19 has yet to be assembled, with the number of infections and fatalities climbing as this story is written. And we don’t know how the arts will fare in the long term after this global catastrophe. Obviously theatre survived the 1918 flu, but at what cost? As in most of the rest of U.S. society, in early fall 1918 keeping the theatres open was viewed as proof positive of national safety. New York City public health commissioner Royal Copeland boasted to the press, “I’m keeping my theatres in as good condition as my wife keeps our home.” In Providence, R.I., the public was assured at the end of September by The Evening Bulletin that “Schools and Theatres Here Not to Be Closed.”

That comforting news notwithstanding, one week later the same paper announced that in fact all schools and theatres would close. Public whiplash was severe as officials oscillated from one extreme to another.

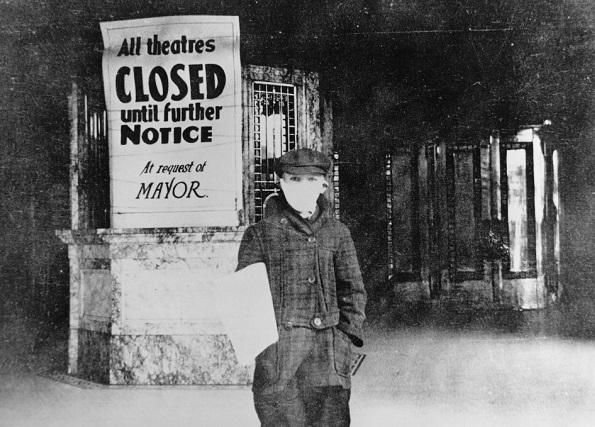

What emerges from this dismaying national picture is the importance of theatre both as a key source of public entertainment and as a measure of the state of affairs. Articles in papers in every state put the status of theatres in their communities on the front page above the fold. Page one of the Richmond, Va., News Leader on Oct. 5 announced that “Every Church, Every School Is Ordered Closed, Also Playhouses.” The three institutions were often grouped together—schools, churches, and theatres—as if they were a single category and of equal importance to the national community.

Theatres were so important that people did not lightly forgo attendance. Their closure remained a great public frustration, even as people were dying. The Seattle Daily Times observed on Oct. 6 that “Theatre Patrons Find Doors Shut, City’s Influenza Prevention Edict Results in Thousands of Disappointments.” Even when people knew in advance the closures were imminent and that deaths were surging, they didn’t relinquish theatregoing easily. In Minnesota, The Minneapolis Morning Tribune reported on Sunday, Oct. 13, that “theatres were packed last night with patrons who took advantage of their last chance to see a performance until the ban is lifted. Long lines of men and women waited in front of the motion picture and vaudeville theaters during the early hours of the evening.” The risk must have seemed worth it.

As the month of October wore on, theatre’s financial concerns dominated the news. Some communities reported on the status of their local artists. The Indianapolis News focused on performers. “Actors Hit by Closing Order,” the paper wrote. The order to close the theatres “that may stretch out indefinitely came into the ranks of the theatrical folk…as a surprise.” The experience for performers was ubiquitous. When the Marx Brothers opened their new musical comedy, The Cinderella Girls, in Grand Rapids, Mich., most of the audience wore masks, which muffled their laughter (which was rare anyway). The show rapidly closed and the Marx Brothers retreated home, unsure, like their colleagues nationally, what to do next.

Typically it was the producers and owners whose losses made the news. Those losses then, as now, were catastrophic. In Philadelphia The Evening Bulletin documented that across two weeks, “Loss to Theatres by Closing, $200,000”—roughly $3.5 million in 2020 dollars. The situation was similar in Milwaukee, Wisc. “Theatres Hard Hit by Closing Order, Loss in Consequence of Dark Houses May Reach Half a Million. Managers Fear That Their Employees May Enter Other Fields” was a Sentinel headline. In 2020 dollars, those managers estimated that they were forfeiting $8-10 million. The paper went on, “The bottom dropped out of the Milwaukee entertainment field on Thursday.” In November, the bottom seemed to be dropping out everywhere.

As losses mounted, some of the drawbacks of being seen as a national institution and treasure, à la churches and schools, began to emerge. In Salt Lake City, at the end of November theatre owners complained that their businesses had been closed while other places where people congregated—bars and restaurants, for instance—remained open. “Of all the business houses, the theatres are the only ones that have been shut up tight. They have been closed now for nearly two months, and many of the theatrical employees are in bad circumstances as a result.”

In Los Angeles demands were far more vehement. In mid-October The Evening Herald noted approvingly that “Theatrical Folk Back Up Health Officials.” By Nov. 7, however, theatre and cinema owners harnessed the power of live performance to make their case for equal treatment. Frank A. McDonald, president of the Theatre Owners Association, and 25 of his colleagues attended a city council session wearing white influenza masks and “appealed not to open theatres, but rather to close up everything else as tight as the theatres… He deplored the fact that department stores, cafeterias, parks, and other places where people still gather, were allowed to be open, while churches, schools, and theatres were closed.” Three weeks later they filed a suit against the city, which was dropped within a few days, when the theatres reopened. In those times, before the Great Depression, the New Deal, and expanded federal and state social services, there was no contemplation of a government bailout nor an expectation of one. Businesses and individuals knew they were on their own.

And then it all seemed to end as quickly as it had begun. An observer in Goldsboro, N.C., remembered, “It was like you flipped a switch. Businesses and theatres opened up again.” And as life resumed, people seemed to forget just how horrific it had been. References to it in 1919 and after were cursory. Theatre Arts Magazine in September 1920 chronicled the new director of a Virginia theatre. In 1917 his predecessor “closed the first season with a production of Riders to the Sea. On the very day of the Dress Rehearsal he was called to Camp where he died of influenza, leaving the impulse without a leader.” This is one of the very few mentions of the recent cataclysm to be found in theatre publications of the time.

It may have been crowded out by another catastrophe. Indeed World War I has occupied tremendous space in the Western cultural memory. Look no further than this year’s multiple Academy Award-winning 1917 or to the 2011 War Horse, which won Tony and Olivier Awards and is still touring. The 1918 flu pandemic received no comparable attention, either then or now. Major literary figures of the 1920s and after ignored the flu in their work, and offered audiences no representations of the disease that rivaled the Great War in its body count.

Theatre literature from the time is no different. Diverse and heterogeneous playwrights wrote about World War I, from Irwin Shaw (who was 5 in 1918) to Alice Dunbar-Nelson (43) to Maxwell Anderson (30). Those who lived through the pandemic, including Eugene O’Neill (who was 30 in 1918), Lillian Hellman (13), Clifford Odets (12), Zora Neale Hurston (27), and Susan Glaspell (42), never treated it as a major subject deserving of consideration. Tennessee Williams and Arthur Miller were children in 1918, and neither of them ever wrote on the catastrophe.

This may seem strange, but it’s worth noting that even the writers of Shakespeare’s time, who lived through the apocalypse of the Bubonic Plague, seldom made it a dramatic subject. “A plague on both your houses” is one of the best known lines from Romeo and Juliet, and while its contemporary audiences may have heard it as a far more chilling curse than we do now, it stands out today as one of the few direct references at the time. Plague became a literary metaphor but not a subject for literature.

One of the few artists who made the 1918 pandemic a focus in their work was novelist and playwright Katherine Anne Porter. A reporter at the Rocky Mountain News, she had only been there a few months when she fell ill. Unlike millions of others, Porter survived. She would go on to memorialize the experience in her 1939 novel Pale Horse, Pale Rider. When the character representing Porter asks her lover what it is like outside, he responds, “It’s as bad as anything can be…all the theatres and nearly all the shops and restaurants are closed, and the streets have been full of funerals all day and ambulances all night.” For Porter, theatre was a key indicator of the national situation.

On the other hand the literature, theatrical and otherwise, from another plague-like virus, HIV/AIDS, has neither been scarce nor insignificant. And there seems little chance that today’s theatre artists will forget the trauma of this time, or fail to let it influence their work, as the writers of 100 years ago seem to have. The art being created now, in quarantine, and in the future, after the threat of COVID-19 infection subsides, is likely to offer us a collective opportunity to remember the uncertainty and fears of this moment, to understand why things unfolded the way they did, and to help us keep them from happening again.

Charlotte M. Canning is head of the University of Texas at Austin’s Performance as Public Practice program and director of the Oscar G. Brockett Center for Theatre History and Criticism.