The 39th annual Humana Festival of New American Plays, hosted by Actors Theatre of Louisville, runs through April 12, with five fully produced world-premiere plays and a series of 10-minute plays. For those who have never attended, it’s a bit like the Sundance Film Festival for theatre, only with better bourbon.

As part of our special Humana coverage this year, we’re interviewing the playwrights while their plays are running there. Previously, we talked to Erin Courtney, Jen Silverman and Colman Domingo.

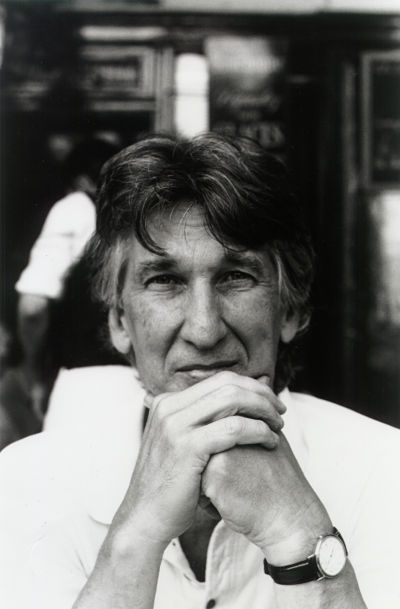

Today’s interview: Charles Mee.

LOUISVILLE, KY.: Charles Mee doesn’t plan on seeing his new play at all—until opening night, that is. Speaking over the phone days before the opening of his newest play The Glory of the World, he explains that he hasn’t even seen the piece in rehearsal. “Years ago I realized that the playwrights who get the best productions are the dead playwrights, because they don’t go to rehearsal,” he explains. “So I leave the directors and actors free to do their thing.”

It helps that Glory of the World has Actors Theatre artistic director Les Waters at the helm. Waters’s relationship with Mee dates back to 2000, when Waters directed Mee’s Big Love at Humana. “We’ve known each other for, I think, 728 years and done a bunch of stuff together, so I totally trust him, he’s wonderful,” says Mee, who has a penchant for the larger-than-life.

This sensibility is reflected in Mee’s sixth foray into Humana. In The Glory of the World, the main character—though he never speaks a word—is 20th-century Trappist monk, poet and author Thomas Merton, who spent a majority of his adult life in an abbey in Kentucky. In the play, a group of men come together to toast the late Merton on the occasion of his 100th birthday and a raucous party ensues, complete with booze, cake-throwing, literary quotes, dance breaks and a cameo from a rhinoceros.

Below, Mee talks about writing an atypical bio-play and his ongoing collaboration with Waters.

So you’ve said that you don’t go to rehearsals of new productions. Is this the same with revivals?

Absolutely, totally. I’ll go and watch [the production] and learn from it and maybe do some revisions based on what I see. Then the next time anybody does it, they do whatever they want. Just the way they do a play from Euripides or Shakespeare. I get treated like Shakespeare or Euripides. It’s good company; I like it.

The Glory of the World was a commission, right?

Well, Les called me and he said, “Would you write a play for the next Humana Festival? In 2015, if Thomas Merton were still alive, it would be his 100th birthday, and this would be a celebration of Thomas Merton on his 100th birthday.”

I said, “Well, sure—although, you know, I’m an ex-Catholic, so I don’t think I can do a sort of wonderful, nice job about a priest. I might do something that gets you thrown out of Louisville!” And he said, “That’s okay, go ahead.”

So it’s a bunch of guys who come to celebrate Merton’s 100th birthday. They offer toasts for his birthday party: “To Thomas Merton the great pacifist.” And somebody else says, “Oh, I don’t know—pacifist, I’m not sure, but I mean, a great Buddhist, and then from that some pacifism would come.” And someone else says, “Oh no no, he was a Catholic, not a Buddhist. I’d say he was a great Communist.” And pretty soon they’re all just in a huge fight, so the party turns into a gigantic brawl, and then as they come out of the other end of the brawl, it turns into a huge celebration of the rich possibilities a single human being is capable of.

The truth is, my father was a devoted Catholic. In the living room, there was bookshelf with Thomas Merton books on it, and I read it when I was 3 years old. You know, my mother and father’s friends would come over for dinner and cocktails and sit in the living room and somebody would say, “Gee, I just read this book by Thomas Merton and he was such a great pacifist.” And someone would say, “Oh, I don’t know if I would say pacifist, I would say a great Buddhist.” So I heard these conversations in the living room when I was a kid.

It’s a tribute to Merton, not a straight bio-play—it’s more about what he meant to these people. Was this angle something Les asked for?

It’s just what happened when I started writing it. It’s [Merton’s] effect on other people, but it’s also about the wonderful richness and complexity most of us all have as human beings. I’m a big believer that theatre shouldn’t oversimplify things and make stuff easy: A causes B causes C causes D. I really think the way the world really is is: A causes B causes C, plus 237, causes purple causes volcanic eruption causes a song and dance. That just seems like real life to me. We human characters are much more complex than the plotline of A causes B causes C.

You’ve also got the pop-culture references.

Oh yeah, I love to do that. You have to understand, I’m a really serious historian, too. If you appropriate stuff from the world today and throw it into the middle of your play—and you can’t change it, because it’s a fact of life from today—then you’ve documented how life is today.

There are also trampolines involved.

You have to talk to Les about that.

What about the rhinoceros?

Actually the rhinoceros was Les’s idea too. We had a couple of conversations on the phone and I was saying, blah blah blah, and Les said, “That’s when the rhinoceros enters.” And I said, “Okay.”

Why?

I don’t know, you have to ask him [chuckles]. [The rhinoceros is almost certainly a reference to Merton’s essay on the Ionesco play. —Ed.]

Since you’ve been to Humana before, do you have a favorite restaurant that you frequent when you’re there?

I do but I can’t remember the name of it! It’s been too many years since I’ve been there. I mean I know how to get there, I know what street to drive down to get there, but I don’t remember anything else. It’s good that I don’t remember because if I told you, there would be crowds of people taking up the space and tables and I wouldn’t be able to get a seat!