There are many tangible ways to measure how The Laramie Project has changed theatre and the world since New York’s Tectonic Theater Project opened the groundbreaking play in Denver 20 years ago, on Wednesday, Feb. 26, in partnership with the Denver Center Theatre Company.

Most evidently, you can look at the estimated 10 million who have seen the play onstage in at least 20 countries and in 13 languages, or the 20 million who have watched the HBO film adaptation, or the 100,000 purchased copies of the script. You might point to the 2009 enactment of the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act, or the landmark 2015 U.S. Supreme Court decision to strike down all state bans on same-sex marriage. You might cite the proliferation of positive queer visibility in pop culture in the two decades since 21-year-old University of Wyoming student Matthew Shepard was robbed, pistol-whipped, tortured, and left to die on a fence on the outskirts of Laramie because he was gay.

Head writer and assistant director Leigh Fondakowski measures the play’s impact by a single performance she attended in Washington, D.C., when a teenager came out as gay during the talkback. “The audience applauded him,” Fondakowski said. “His life changed forever, and for the better, in that moment. Our play created a space for that.”

The Laramie Project, drawn from 200 interviews conducted by artistic director Moisés Kaufman and nine members of his Tectonic Theater Project in the year following Shepard’s murder, is now routinely studied in schools as a method for teaching about prejudice and tolerance. The brutal murder—and Tectonic’s efforts to understand both its underlying origin and the community’s attempt to heal—led to a profound reckoning of American values. What happened in Laramie, Kaufman said, “was a watershed moment for the country.”

Perhaps the greatest measure of this story is the journey taken by Shepard himself since Aaron McKinney and Russell Henderson left him so beaten and bloodied that the first passers-by mistook Shepard for a scarecrow. Today, his interred ashes rest in the sacred space of the Washington National Cathedral.

At an appearance in Chicago last October, Judy Shepard credited The Laramie Project with humanizing her son’s story for the world and keeping him alive in their popular imagination. “I think every school should be performing The Laramie Project,” she said.

The mere fact of the play’s existence, much less its worldwide performance history, “has made the world a better place,” said Jason Marsden, executive vice president of the Matthew Shepard Foundation. “It has given courage and pride to besieged, misunderstood souls in Uganda. It has defied homophobia in rural Poland. It has helped numberless LGBTQ+ people young and old to stand up, come out, and live their truth. It has gently queered the high-school literary canon and literally inspired the formation of entire community theatres in rural America.”

In the 2002-03 theatre season alone, there were 440 professional, amateur, and school productions of The Laramie Project, according to The New York Times. Tectonic statistics show there have been 2,273 licensed productions over the past 10 years, which is as far back as their records go.

“Night after night, year after year, The Laramie Project has sent audiences home with fresh insight and questions about their own hearts and those of their neighbors,” Marsden said. “And it shows no sign of ever stopping.”

That’s what most fills Kaufman with gratitude. “The fact that humans of all ages and backgrounds from all around the world are willing to carry that torch of The Laramie Project onward fills me with hope for our future,” Kaufman said.

And yet…

Hate crimes motivated by bias or prejudice reached a 16-year high in 2018, according to FBI statistics. And, even in 2020, Wyoming remains one of only four states without a single hate-crime statute.

“The fact that hate crimes are on the rise technically tells us only that more of these crimes are being reported,” Marsden said. “But the fact that this rise has occurred across all categories, be they religious, racial, ethnic, sexual or gender-related, at the same time that a measurable rise in hateful rhetoric is also going on in our country, is probably also telling us that more people feel free to subject their neighbors to criminal attacks based on their identities. And that tells us, grimly, that we likely have even farther to go than we did five or 10 years ago.”

An Artistic Response to Atrocity

When Kaufman learned of Shepard’s murder on Oct. 12, 1998, he posed this question to his company, based 1,800 miles away in New York City: What can we do as theatre artists to respond to this incident, and, more concretely, is theatre a medium that can contribute to the national dialogue on current events?

“The idea that a company of theatre artists could go somewhere, talk to people, and return with what they saw and heard, interested me deeply,” Kaufman said. It also terrified him. “But there are moments in history when a particular event brings the various ideologies and beliefs prevailing in a culture into sharp focus,” he said. “The murder of Matthew Shepard was one of them. In its immediate aftermath, the nation launched into a dialogue that brought to the surface how we think and talk about homosexuality, sexual politics, education, class, violence, privileges and rights, and the difference between tolerance and acceptance.”

More than anything, Kaufman wanted to know: How is Laramie different from the rest of the country, and how is it exactly the same?

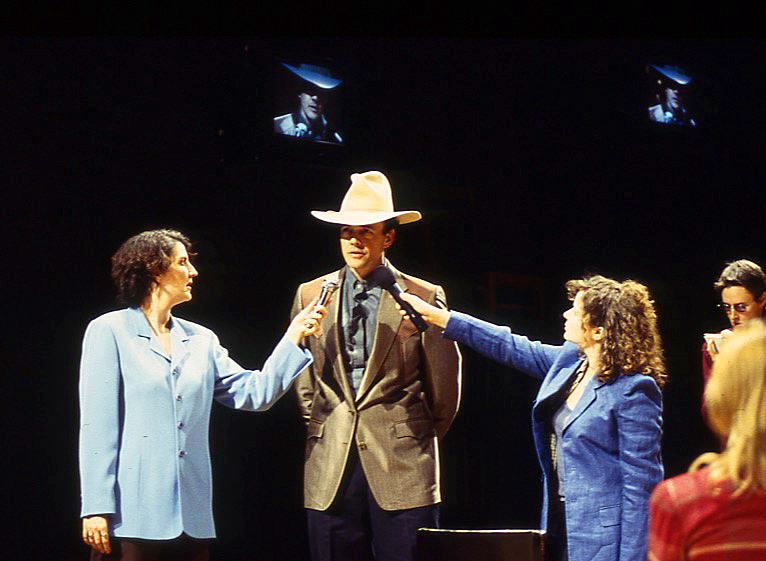

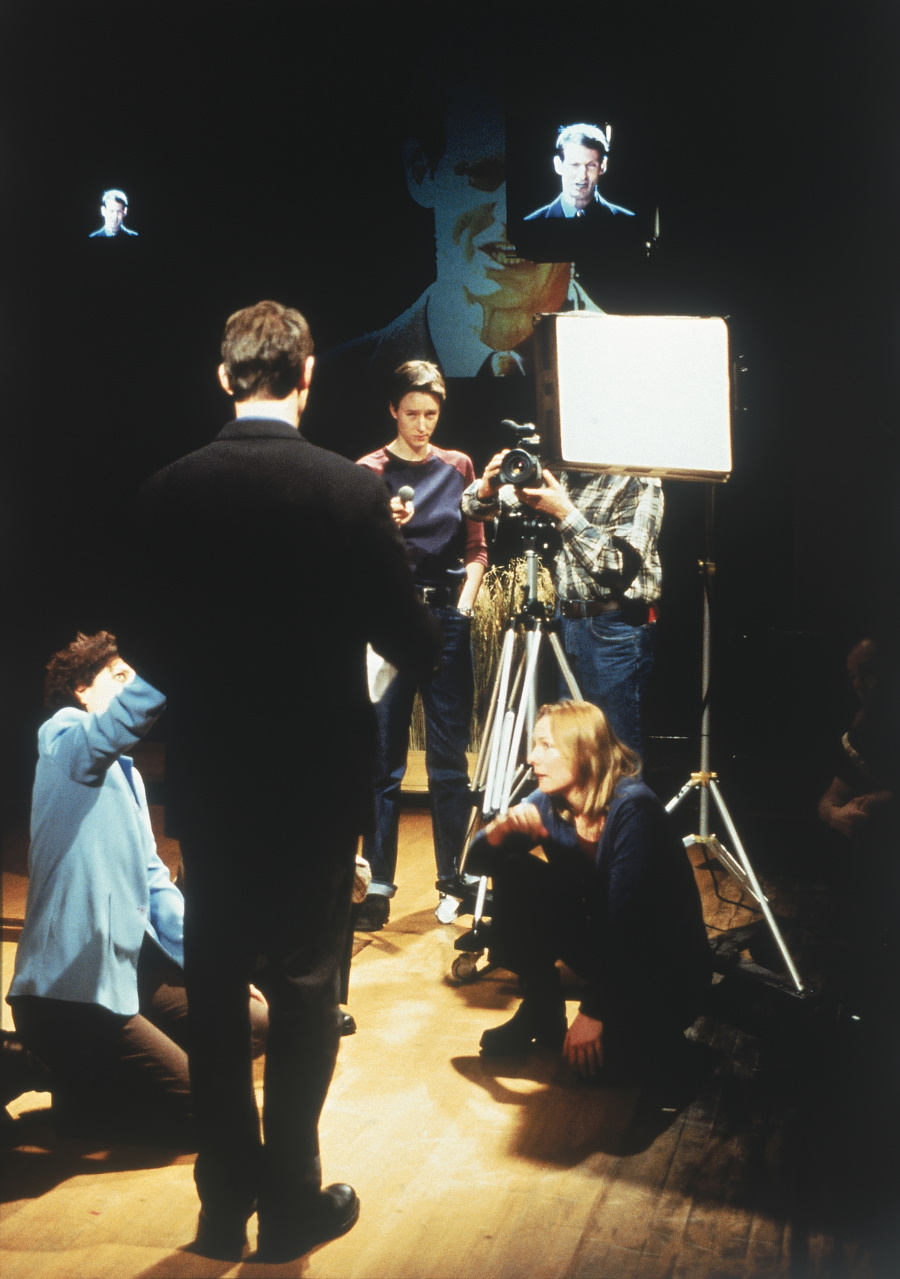

Just one month later, on November 14, 1998, 10 members of Tectonic Theater Project arrived in Laramie for the first of six trips to interview citizens of the town. They were Kaufman, Fondakowski, Stephen Belber, Michael Emerson, Amanda Gronich, Jeffrey LaHoste, Sarah Lambert, Maude Mitchell, Andy Paris, and Greg Pierotti. (Later trips included Betsy Adams, Robert Brill, Mercedes Herrero, John McAdams, Barbara Pitts, Greg Pierotti, and Kelli Simpkins.) Of that group, only two had ever conducted interviews of any kind before. So rather than talking, they just listened. They met friends and relatives of Shepard and his killers. Politicians. Ranchers. Professors. Law Enforcement. Clergy. Neighbors.

“One of the first things we noticed was that the diversity within our group turned out to be a great advantage,” Kaufman said. “Each participant had his or her own interests. Some members wanted to know about the ranching community, others about the gay and lesbian community, others about Matthew Shepard, and still others about the perpetrators. So in a very natural way, we began to hear a rich and varied collection of community voices.”

It is important to note, Kaufman added, that Tectonic was not interested in creating a play about Shepard himself, or his killers. It is instead a play that tries to capture immediate reactions to the murder and explore the underlying bigotry and hatred that enabled it.

Kaufman described that year as “one of great sadness, great beauty, and, perhaps most importantly, great revelation—about our nation, about our ideas, about ourselves…As a group of theatre artists from New York City, we had many, many misconceptions and preconceptions, all of which proved to be very far from the truth. There was no way for us to imagine what people would tell us.”

Each time the ensemble returned to New York, they would spend a month creating the characters and “moments” (Tectonic does not call them “scenes”) that would become the working script. Tectonic did not invent interview-based theatre, which has a long history, including the Studs Terkel musical, Working (1977), Anna Deveare Smith’s Twilight: Los Angeles, 1992 (1993), and Eve Ensler’s The Vagina Monologues (1996). “But we knew that we were expanding upon the form by having the actor who interviewed the real-life person also play the person they had personally met,” Fondakowski said. “So the audience was just one degree of separation from the actual person, and the connective tissue was the empathy of the actor.”

Tectonic further developed its material at Robert Redford’s Sundance Theatre Lab in Utah and at the New York Theatre Workshop. The decision—and the deal —to hold the world premiere at the Denver Center came together very quickly. On Kaufman’s way back to New York after attending the trial of Russell Henderson, he stopped in Denver and worked out an arrangement with then-Denver Center Theatre Company artistic director Marley (and a whole bunch of lawyers). A hastily arranged press conference was called to announce the deal on Nov. 10, 1999, just hours after the contract was signed. Rehearsals would start just two months later, with a run of Feb. 26 through April 1, 2000. Just six weeks after that, The Laramie Project moved to New York’s Union Square Theatre.

“Because this incident had taken place in the West, it became important to us to premiere our piece in the West, which is why we accepted Donovan Marley’s generous invitation to start the next part of our journey in Denver,” Kaufman said. “Thus began the all-important next phase that included the presence and participation of the audience.”

Marley said felt he felt a moral imperative to host the premiere at the Denver Center, given its proximity just 130 miles south of Laramie.

“There are two important legacies here,” said Marley. “For the theatre world, it was a validation of Moisés Kaufman’s brilliant vision of creating important topical works for the theatre by total immersion of his actors in researching the story and then developing the text together. But the broader and more important legacy is the impact on the audience of the ensemble’s humanizing of Mathew Shepard so that a homophobic America could find a son or a brother crucified on a Laramie fence—and resolve to change the culture.”

Fondakowski called Marley’s faith in the unseen—and unfinished—work a remarkable show of faith in the project.

“He didn’t think about the commercial viability of the play or the size of the cast or the risk in an untried work—or maybe he did, and did it anyway,” Fondakowski said. “He said to us: ‘I trust you to tell this story, even though you haven’t proven it yet all the way.” That was an empowering moment that compelled us to make our highest and best work.”

The Denver Chapter Begins

When Tectonic company members arrived in Denver, the had only two acts, “because Moisés wasn’t sure the audience could sit through a three-act play with such challenging subject matter,” Fondakowski said. “It was through the rehearsal process that we discovered the third act should revolve around the trials of the two perpetrators, Russell Henderson and Aaron McKinney.”

To many, the singularly indelible moment of the play comes when Dennis Shepard speaks at Aaron McKinney’s sentencing hearing, and takes the death penalty off the table: “Mr. McKinney, I am going to grant you life, as hard as it is for me to do so, because of Matthew. Every time you celebrate Christmas, a birthday, the Fourth of July, remember that Matt isn’t. Every time you wake up in your prison cell, remember that you had the opportunity and the ability to stop your actions that night. You robbed me of something very precious, and I will never forgive you for that. Mr. McKinney, I give you life in the memory of one who no longer lives. May you have a long life and may you thank Matthew every day for it.”

Throughout the entire Denver run, scenes were cut, added and rearranged. And the eight actors playing 60 characters not only rolled with it—they held the scissors. “Stage management at the Denver Center made these very large poster boards with the order of the show on any given day posted in the wings,” Fondakowski said. “So actors would be running offstage for their costume quick-changes and looking at the poster boards to see which scene came next. It was harrowing, but also exciting in its own way. The play was truly a work-in-progress that was constructed collaboratively. But the Denver audience became our final collaborator: How they responded to the play directly impacted how we ultimately finished it.”

No one knew what to expect from those first Denver audiences. Laramie was a small university and ranching town of 27,000. Denver was a nearby metropolis of 2 million, and a community still very much reeling just months after the massacre at Columbine High School.

Fondakowski’s strongest memory of opening night is a feeling of nervous excitement. She had zero sense that this was the start of something that would have so much impact on American theatre, culture, and politics. She was just grateful that the audience responded, as she put it, respectfully and positively.

“You have to remember, this was not the world we live in now in terms of gay representation onstage and in the media and in the world as a whole,” she said. “We weren’t sure the audiences in the West wouldn’t be homophobic and reject the play on the basis of their morality or religion. Instead, the Denver audiences responded with the kind of dignity that elevated the story and uplifted the narrative to an almost iconic status. I remember feeling very moved that they listened, that they cared, that they were engaged. Matthew’s story was legitimized.”

The New York run that immediately followed, however, “was not commercially successful,” Fondakowski said. “We had no idea the play would have a life beyond the original company who made it.”

The company fulfilled its promise to the people of Laramie by bringing the play there in 2002. An initial small burst of professional productions began to wane, when something unexpected happened: a slow burn. “Amateur productions just started popping up,” Fondakowski said. “Then more and more colleges did the play. Then high schools.”

That same year, HBO released a film adaptation featuring major stars jostling for the opportunity to lend their support, including Laura Linney, Peter Fonda, Steve Buscemi, Christina Ricci, Bill Irwin, Janeane Garofalo, Ben Foster, Terry Kinney, Amy Madigan, Dylan Baker, Michael Emerson, Kathleen Chalfant, and Clea Duvall.

From there, the slow burn grew into a groundswell. Clearly, Fondakowski said, “This play was needed. This play became a way for theatre companies and students everywhere to talk about homophobia in the places that they lived.” The Laramie Project has since been staged everywhere from Kaufman’s hometown in Caracas, Venezuela, to Norway and South Korea.

Ten Years Later

Members of the Tectonic Theater Project returned to Laramie to create the companion piece The Laramie Project: Ten Years Later, which debuted as a reading in 150 communities around the world on Oct. 12, 2009 on the 11th anniversary of Shepard’s murder.

Tectonic members did not interview either of the killers for the original play. But this company of non-journalistic artists made national headlines when company member Greg Pierotti landed a jailhouse conversation with McKinney, the first he’d agreed to with any “reporter” in five years. At a time when many were writing off the Shepard murder as a robbery gone bad, McKinney bluntly told Pierotti: “Matt Shepard needed killing. I don’t have any remorse. The night I did it, I did have hatred for homosexuals.” McKinney targeted Shepard, he said, “because he was obviously gay. That played a part. His weakness. His frailty.”

From that moment on, no one could ever again credibly argue that this was not a hate crime. “Greg Pierotti is the bravest man I have ever met,” Fondakowski said. “The conversation he had with McKinney was remarkable on so many levels. I’m not sure that people won’t still argue that this was not a hate crime, especially in this era of ‘alternative facts.’ I do think, however, that for generations to come, we have this record, based on Greg’s commitment to the truth, and his courage to sit face to face with a murderer and try to better understand him. Why do this? So that humanity as a whole can heal, and art can provide the space for that growth and reflection.”

Ten Years Later also chronicles advancements in the gay-rights movement. Jim Osborn, a close friend of Shepard’s and a “living character” in Ten Years Later, paid a visit to Denver School of the Arts in 2015 on the occasion of it becoming the first high school in the country to have staged both parts of The Laramie Project. “It’s all horrible, isn’t it?” Osborn told the students. “We don’t like to talk about things that hurt us, but we have to. Because otherwise, we end up growing new Russell Hendersons and new Aaron McKinneys.”

But, he also told them, things are getting better: Two months before, he said to cheers, Osborn and his husband had become the first gay couple to register for a marriage license in Johnson County, Wyo.

The L words: Laramie and Legacy

Fondakowski says it has been “incredibly moving” to see how vital The Laramie Project has been in the life of so many communities over the past 20 years. “The downside of this, of course, is that the play remains vital, when in fact it should feel historical or outdated by now. The fact that it’s not, and that this could still happen anywhere at any time—and does, just without the same media attention—is a call for us to not grow complacent.”

For all of the monumental social changes that have happened since 1998, she added, not enough is being done to protect gay, queer, trans, and non-binary people in their day-to-day lives. “Visibility in the media is a wonderful advancement, but it can also lead to a false sense that our rights and protections are in place,” she said. “Women have the same issues. Trans women and Trans women of color have prejudice coming at them from every angle. We have language now to name the discrimination, and we have some legislation and some protection in place. But it may not be in my lifetime that we are free of violence and discrimination.”

But then she thinks about the time she attended a school production of The Laramie Project and saw a boy not even yet 15 portray Harry Woods, a 52-year-old gay Laramie resident. “This boy was not gay,” she said, “and yet I saw him play Harry Woods in the most convincing way I have ever seen him played. He stood up and said, ‘I’m 52 years old, and I’m gay.’ Now, there is no other art form that can allow for a 15-year-old boy to convincingly say those words. I’m grateful to the theatre as a form that has so much potential, and for the young people everywhere who still believe in the power of theatre to change hearts and minds. Theatre does have an important role to play in the important conversations of our time.

“To me, the legacy of The Laramie Project is the fundamental belief that art matters in the health and vitality and humanity of society.”

John Moore, cited in this American Theatre round-up of influential U.S. theatre critics when he worked at the Denver Post, has since taken the groundbreaking position of Denver Center’s senior arts journalist.