At approximately 6 p.m. on Tuesday, Dec. 24, during the final curtain call of the final show in the final year of his astonishing 40-year run as Ebenezer Scrooge in South Coast Repertory’s (SCR) A Christmas Carol, Hal Landon Jr. will get the last laugh.

Or, one should say, he deserves the last laugh, because he’s earned it. Not for defying time or age, though any 78-year-old who still possesses the stamina, memory, and dexterity to drive an entire play 40 years into its run has earned that. He’s earned it by beating genetics at its own game.

For midway through the journey of his life, Hal Landon began losing his hair. And wound up finding a crown instead.

“Well, that’s one way of looking at it, I suppose,” says Landon, in a tone that suggests he’s never looked at it that way, and anyone who would look at it that way has far too much time to look at some things a certain way. The “it” is whether Landon has ever pondered the irony that losing his hair at a relatively young age may have played a key role in keeping him a leading man for 40 years, at least during the holiday season.

So his answer doesn’t support my hypothesis. Fine. And maybe calling the actor who plays the character of the emotionally isolated miser at the center of the 1843 Charles Dickens novella as a leading man is just as ridiculous. Scrooge is the protagonist of A Christmas Carol, surely, but he’s more of an archetype, a character symbolizing the quintessential miser on the temporal level, and the possibility of transformation on a more Jungian, unconscious level (it’s not such a reach, as what triggers Scrooge’s conversion? Dreams).

So the actor playing him doesn’t need to possess the romantic traits of a matinee idol, the ruggedness of the tough guy, or the heart of gold of the everyman. He just needs to play an older, emotionally shut down person, and it doesn’t matter if his dome is as shiny as Yul Brynner’s or as hirsute as Jason Mouma (on second thought, maybe too much hair doesn’t suit Scrooge).

It’s not like the hair thing is totally out of left field. As SCR’s co-founder David Emmes told me when I asked why Landon was cast as Scrooge, “We have to tease him that he was cast because he had the least amount of hair and could look older.”

But while getting a part that has lasted for 40 years is a kind of silver lining, losing his hair in the prime of his personal life and acting career stung plenty. As Landon says when asked whether losing his hair was a big deal, “Yes, and I have resented it every minute since.”

This may seem like an odd entry point into a story about an actor who is a Southern California cultural institution, who has entertained children who have brought their children to see him perform, who has played the role of Ebenezer Scrooge an estimated 1,400 times, a record apparently unmatched in U.S. professional theatre history.

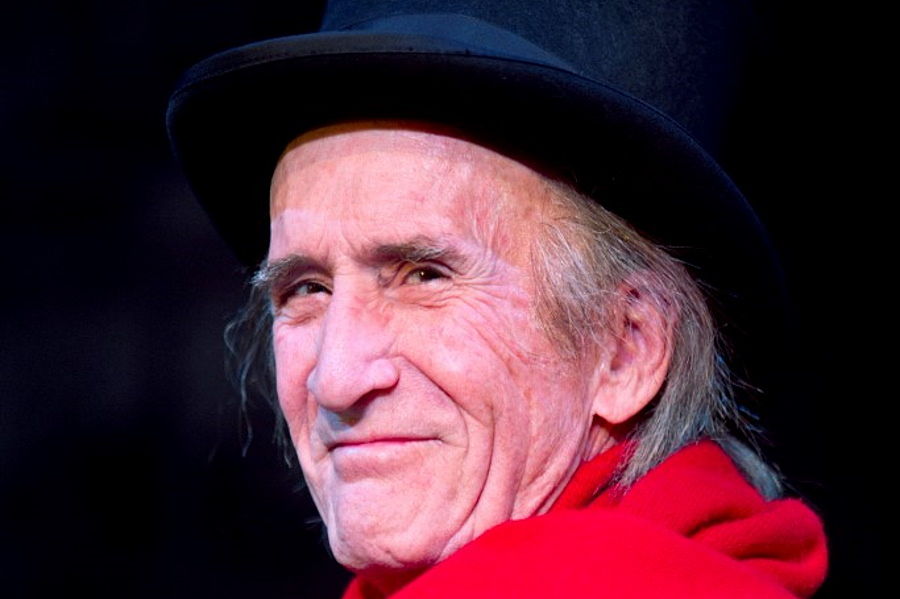

That milestone having been reached, Landon is finally hanging up the red scarf and black top hat after this, his 40th year. It should be a time of celebration tinged with bittersweet poignancy. Goodbye, Hal Landon. Thanks for the memories. Speaking for myself, your Scrooge has made my Christmas for so many years.

Not that Landon is going away. He’s still going to act, whether returning as Keanu Reeves’s dad in the belated third installment of the Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure franchise or onstage at SCR or another local theatre.

And to be clear: Landon isn’t Ebenezer Scrooge. When he walks off that stage Dec. 24, leaving all that he created for so long behind him, he’ll be the same Hal Landon who walked onto that stage the first night of his incomparable run, just 40 years older, and with even less hair.

But just as the story he has enacted night after night, year after year, doesn’t begin in the middle, neither does Landon’s. So let’s start the story long before thoughts of Scrooge, or SCR, or even acting ever entered his head.

Hell, why not start it when that head still had all its hair?

Landon was born in Tucson, Arizona, but grew up in Los Angeles until he was 9, when his dad, Hal Landon Sr., moved the family back to the desert after his own film career dried up. His most memorable role was untitled; he’s the good-looking kid who hands the high school pool key to Alfalfa, a.k.a. Carl Switzer, in It’s a Wonderful Life. (A beautiful footnote: Both Landons appeared in a 1978 production of the play The Comedians, which happened to mark the first time SCR was mentioned by The New York Times; Hal Sr. got a good notice.)

While his parents acted at a local playhouse, Hal Jr. pursued athletics, including diving for the local YMCA, which may account for how, some 60 years later, he’s still able to do Scrooge’s dazzling somersault onto the bed, cram his head into a hat, and land on his feet, hat in place. But by the time of his junior year, the 5-foot, 11-inch Landon had settled on basketball.

After graduating from Catalina High School in 1959, he enrolled at the University of Arizona. He wasn’t quite sure what he wanted to major in, but he knew what he wanted to do: play hoops for the Wildcats, who’d had some decent seasons under Fred Enke up until the early 1950s, but finished 4-22 Landon’s senior year in high school.

So he tried out for the team as a college freshman; he didn’t make the cut. Though he felt “devastated,” Landon figured he’d try something else. Since he’d grown up around actors, why not give acting a shot?

Foreshadowing much of his early acting career, Landon was cast as the lead in his first college play, an adaptation of Thomas Wolfe’s novel Look Homeward, Angel, which netted playwright Ketti Frings a Pulitzer Prize in 1957. Though he thinks he may have landed the role based as much on the director knowing his father as his natural ability, Landon was hooked. Not because it was effortless—because it was so difficult.

“You had to portray real emotion and kiss a girl onstage and all kinds of stuff, and I had no training,” he recalls. It took him nearly a year to get back onstage, mostly because, he says, he didn’t think he had come close to realizing the part’s potential.

That inner struggle—of being cast for parts based on type as well as ability, but with a nagging feeling that he hadn’t quite hit the mark—was a constant for Landon for nearly two decades. Although he didn’t know it at the time, what he needed was some way to ground his acting.

“Some actors need solid technique, some don’t,” Landon says. “I apparently do.” His college theatre department “didn’t focus much on teaching a technique; mostly it was doing a lot of scenes and plays. But they did great stuff. They were doing Pinter and Beckett in the very early ’60s when hardly anyone else was doing it.”

But though he was an actor in search of a technique, he was not an actor in search of a type. Athletic, hardy, tall, an avid outdoorsman, he was a natural fit for manly-man roles, such as the one he scored in a summer Shakespeare festival in Claremont shortly after graduating college: the swaggering sack of testosterone named Petruchio in Taming of the Shrew.

Then he made his way to San Francisco to check out the Actor’s Workshop, a groundbreaking company founded by San Francisco State professors Herbert Blau and Jules Irving. The two had just left for New York, but Landon spent a season working with the company. It was there that he first heard about a group of former workshop students who had gone south and formed their own company in a place called Orange County. He’d never heard of it, but learned it was just east of Los Angeles County. Since his dad was now living in Arcadia, about 13 miles northeast of Los Angeles at the base of the San Gabriel Mountains, and the town the company was in at the time had the word “beach” in it—why not check it out?

Landon rolled into Newport Beach on a November night in 1966 and discovered the company working in a converted 75-seat theatre on the Balboa Peninsula that used to be a marine hardware store. The play, directed by Emmes, with SCR’s other co-founder, Martin Benson, in the cast, was called Let’s Get a Divorce, adapted from the French farce Divorçons. Benson claims Landon hated the show; for his part, Benson says, “I was brilliant!”

But the stage had been set. Landon wouldn’t find intensive acting technique training here; the company had no time to coach actors, as it was too busy performing one show and rehearsing another while frantically trying to live up to a future mapped out years before by Emmes and Benson on a dinner napkin.

But he’d found a home. Landon was the last of SCR’s six founding artists, the ones who joined the company in its early days and stuck it out through seasons lean and plentiful. That commitment was ultimately rewarded with the designation of founding artist, which sounds cool—but way cooler than the title is the fact that when SCR got in a position to pay staff and offer actors union contracts, each of these founders—Landon, Ron Boussom, Richard Doyle, Art Koustik, Martha McFarland, and Don Took—was guaranteed 26 weeks of acting work until they were 65 years old.

All were talented and versatile enough to play an array of characters, and in the early years, when SCR was a company numbering fewer than 20, all played roles big and small. But Landon’s roles tended to reflect a certain type.

Remember: At the time he didn’t yet look like the actor who would roam SCR’s big stage for 40 years during the holidays, described by Rob Weinert-Kendt in a 2004 review of Carol in the Los Angeles Times as “preposterously thin and craggy, [lacking] the jowly, harrumphing bluster we’re used to in Scrooges…perversely rigid in his petty hatreds and clownishly elastic in his inevitable softening.”

The Landon of these early years was a nature-loving athlete. Jerry Patch, SCR’s literary manager its first 37 years, remembers trekking with Landon in California’s Sierra Mountains for seven days. “He was a man’s man,” Patch recalls, or “someone who just had that affect.” Benson remembers Landon as “more a leading-man type in those days. He had hair—a good-looking guy, much beefier than he is now.”

He also had good theatrical instincts. At one point in 1969, when the fledgling theatre was on the ropes, they took on Joseph Heller’s fervently anti-war play We Bombed in New Haven, which had just bombed in its New York debut. “It was kind of a crazy choice, but we believed in it and we figured if we’re going to go down, we were going with guns blazing,” Benson recalls.

His solution to the play’s problem: “I was going to trick it up with a lot of technical effects.” But then he heard a dissenting voice in an early rehearsal, asking him, “Why? Don’t you trust the play?” Benson reconsidered, cut the effects, and the play was a hit. At one point during the run Benson remembers walking into a bar across the street and saying, “Okay, guys, we have our options back. We can do anything now.”

The actor who urged him to trust the play? Hal Landon Jr.

“He was absolutely right,” Benson says.

Landon would appear in at least 20 productions his first four seasons with SCR, including starring as the roguish anti-hero McMurphy in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest to the broodingly sensual Stanley Kowalski in A Streetcar Named Desire. But the clock was ticking on those kinds of parts, and not only because as SCR’s reputation grew it no longer had to cast from within the company. Landon was going bald. Big time. Whatever disparaging remark about a man losing his hair you can think of, Landon (as all those of us who have endured this humbling ordeal can attest) was hearing it.

That didn’t mean there would be no more acting work; he was too talented, committed, and affable to give it up. And there was no shortage of roles in the theatre for actors over 30, full-maned or not; it’s not like he was a woman (😬). But a funny thing happened to Landon on his way to what probably would have been a fruitful and fulfilling career as solely a character actor: SCR blew up.

Thanks to its work on the stage and great planning (and some schmoozing of the right people), SCR had become a fully professional house by 1976, with a paid staff and paid actors. And in September 1978, thanks to the largesse of the Segerstrom family and a $3.5 million building campaign, the curtain rose on a new 507-seat theatre in Costa Mesa, owned and operated by the company itself.

A bigger house meant more staff and bigger costs, and with greater visibility came greater expectations. The two-person brain trust of Emmes and Benson made a fateful decision: a holiday show. If successful, it could mean both short-term and long-term success: butts in the theatre, and a way to endear SCR to the bigger community it now served.

It wasn’t an idea longtime SCR adherents, more accustomed to Brecht, Pinter, Rabe, and Shepard, might expect from the company. But Patch’s adaptation, which premiered in December 1980, was an immediate hit. In its 40 years, the show—which has never been offered as part of a subscription package, and after its first few years cost SCR nothing apart from turning on the lights and paying the cast and crew—has helped underwrite many of SCR’s other efforts. Maybe just as important, it helped the theatre forge an indelible link with its community.

“It is the one production the entire year that speaks to the entire family, and I cannot think of a better example of SCR’s reputation of being a resident theatre and being a part of the community and serving the community than that show,” says Emmes.

Forty years in, it’s still Patch’s adaptation that John-David Keller once more directs, and many in the cast and crew have been there for decades

Yet there’s one actor’s face on the billboards and one actor’s performance that has defined the SCR Carol. Whether you can call the part of Scrooge a leading man or not, Landon is the Man. Maybe Patch had Landon in mind when he adapted Dickens’s novella (memories being what they are, everyone’s is slightly different on that count; Landon doesn’t think so). Or perhaps the role fell to Landon because he was follically challenged and just looked older. Or, most likely, Landon became Scrooge because he had long established himself as, in Benson’s words, a “great actor to work with, always had his lines, always on time, and the talent speaks for itself.”

Whatever the case, it’s been Landon’s 40 years, and nothing has changed in that time, right?

Wrong.

Remember Landon’s self-doubt after his first acting role? He began feeling something similar about his Scrooge a few of years into Carol.

“When we started, the idea was to do a family show, since SCR didn’t have anything like that at the time,” Landon says. “But I guess we got in our heads that a family show means this needs to be really entertaining to the kids. As a result, we emphasized all the comedy but kind of neglected the other side. There were people who really liked it and people who wish we were still doing it the same way. But I think we realized that that wasn’t what Dickens really intended, and so we started trying to find the deeper meaning of the play and bring out the social consciousness.”

What Landon learned, which he brought to the director and adapter, is that while Dickens wrote A Christmas Carol for children, it wasn’t to entertain them but to save them—in effect to prod adults to change the miserable conditions that poor children and anyone else on the negative side of England’s Industrial Revolution ledger were living in.

All parties agreed, and thus began a process, with a line modification there, a change of music here, a tweaked lighting cue or two there—all designed to make Scrooge’s transformation more human and to underscore the terrible necessity of change that Dickens felt English society needed. When fully realized some 12 years into the run, according to reviews in the LA Times and Orange County Register, the show’s more mature, darker tone at last reflected what Landon and company felt was truer to Dickens’ intent.

“From the very beginning we were playing a broad comedy, trying to get the laughs, whatever made the audience happy,” Koustik recalls. “But Hal, through his research, and supported by John-David, made his character more real, so we had to do the same thing.”

Adds Doyle, “It is a darker production in that actors are going to the darker places. But it is a play rising out of that muck of Victorian England. They were terrible times for people to rise above, and that’s what the journey is about. Some of the raucous laughter and tweaking the funny bones of younger audience members was sacrificed for those moments that help Scrooge on this journey of recovery… it [didn’t] change where the audience goes, it [made] them feel Scrooge’s journey a bit more.”

But a darker, more human show is not the reason it still works 40 years later. Nor is it the set or costumes, the lighting, sound or any other theatrical accoutement; it’s that the man at its center has been working, transforming his character, albeit subtly at times, year after year.

“Hal has definitely put his own stamp on it,” says Patch. “Every year, he tries to take a different perspective. Some years Scrooge is more emotional, some years he’s angrier. But whatever he wants to do with it, at the core, it’s still Hal, that man. He’s a good guy, and he understands that Scrooge’s journey is one of redemption, and that restores faith in life and people.”

Why keep tweaking it each year? Why fix what isn’t broken? Because that young actor who didn’t feel satisfied in his first role is still part of Landon. About 14 years into his life as a working actor when, Landon recalls, “I still felt pretty frustrated. I had this sense that I wasn’t quite as believable as I should be, that I was forcing it. I even tried to quit for a year but that didn’t work. I realized that either I have to get better or I have to give this up.”

That’s when he discovered Michael Chekhov’s book To the Actor. For whatever reason, it appealed to Landon, though it was “a tough book to take from the page and put into use,” he explains. Then he learned that the person Chekhov had dedicated his book to, George Shdanoff, was teaching an acting class in Los Angeles. Landon signed up, and finally found the technique he had been looking for.

“[Shdanoff] was taking what Chekhov was doing instinctually and forming it into acting technique,” Landon says. “So I studied with him on and off for four years, and that really changed it for me. I felt I took a big step forward after that—as a matter of fact, that’s around the time I first started to do Scrooge, and I used a lot of the stuff I had learned from him in developing Scrooge.”

At the risk of gross oversimplification, let’s grossly simplify. Basically, Landon says that through learning ways to meld the physical and the psychological, he was able to center himself in the character and operate from that center. That focus helps him to get and remain in the moment onstage, and frees him to explore different facets of a part, especially from performance to performance. This is no doubt one reason why his Scrooge seems so remarkably fresh and vibrant year after year.

But come the evening of Dec. 24, all that work will be done. It’s time. As Landon tells it, what usually happens is, you either leave too late or too soon. And all things being equal, Landon would rather leave too soon. Plus, he says, “40 seems like a good, round number.”

Next year there will be another actor playing Scrooge, or perhaps a new version of the play. Landon’s effort will be just memories. But those memories are also a monument—not one that can be touched or viewed, but one that will resonate in the hearts and minds of all those who have seen his work these past four decades.

Who knows what will be going through Hal Landon Jr.’s mind at approximately 6 p.m. on Tuesday, Dec. 24, during the final curtain call of the final show in the final year of his astonishing 40-year run as Ebenezer Scrooge in South Coast Repertory’s A Christmas Carol. Maybe it will be relief, or satisfaction, at ending a triumphant run still physically and mentally capable of pulling it off. Maybe he’ll think of the show’s not-so-secret weapons, the bright-eyed kids who act in it every year and who possess the true holiday magic, including his daughter and his granddaughter, both of whom have appeared onstage with him. Or the many souls that the journey of Scrooge he’s curated have touched, those who have been reminded that our fates are not written in the stars, that our hearts can embrace life as surely as they can reject it, that there still remains a place on the table for the milk of human kindness.

Who knows? But it’s a safe bet that buried somewhere in that creative, studious mind, there’s one thing Hal Landon will be stewing about, even if, just maybe, he should be thanking it: losing his goddamn hair more than 40 years ago.

Joel Beers is an Orange County–based freelance journalist and an adjunct communications professor at California State University–Dominguez Hills. He was theatre critic of the now-defunct Orange County Weekly since its first issue in 1995.

A Christmas Carol at South Coast Rep. Adaptation: Jerry Patch; direction: John-David Keller; scenic design: Thomas Buderwitz; lighting design: Donna & Tom Ruzika; costume design: Dwight Richard Odle; music: Dennis McCarthy; sound design: Drew Dalzell.