Minutes after hearing Native Gardens read aloud by her cast for the first time, director Melissa Crespo wanted to talk about neighbors. “I’m one of those people who likes to know who I’m living near,” she said to the cast following the table read.

It was Jan. 22, the day after Martin Luther King Jr. Day and 32 days into the nation’s longest-ever government shutdown, which would last 3 more days. Some 800,000 federal employees were without a paycheck for much the same reason Crespo and her cast sat around a table in Syracuse, N.Y.: a border dispute between neighbors.

“Walls are very much in our lives right now—they’re constantly being talked about,” Crespo said after the reading in the Syracuse Stage rehearsal room while Lulu, her rescued Basset Hound mix, sat on her lap. The Brooklyn-based director is at the helm of a three-way co-production of Native Gardens, which first ran at Syracuse Stage Feb. 13-March 3, would move on to the Geva Theatre Center in Rochester, New York March 26-April 21, and will wrap its run on Portland Center Stage’s U.S. Bank Main Stage May 18-June 16.

Along with Crespo, the four lead actors—Anne-Marie Cusson, Paul DeBoy, Erick González, and Monica Rae Summers Gonzalez—are traveling with the production to all three locations. The silent Latinx gardener roles are cast locally in each city (in Syracuse they were played by Baker Adames, Luis A. Figuerosa Rosado, Aaron J. Mavins, Isabel Rodriguez, and Devante Vanderpool).

Native Gardens has been wildly popular among regional theatres, sliding into the eighth slot of the American Theatre’s Top 10 Most Produced Plays of the 2018-19 season, with a dozen productions at TCG member theatres. Penned by one of the 10 female writers on that list, it helped earn Zacarías the fifth spot on another of AT’s lists, the Top 20 Most-Produced Playwrights of 2018-19. Both lists were the most diverse they’ve ever been, with Zacarías one of 6 playwrights of color and 11 women on the playwrights’ list.

Native Gardens also marks a breakthrough for the 45-year-old Syracuse Stage: It’s the theatre’s first creative team entirely composed of women of color. This includes Zacarías, who was born in Mexico and lives with her family in Washington, D.C. “It’s an overdue milestone for our theatre,” said Robert Hupp, now in his third season as Syracuse’s artistic director. Hupp said the theatre did not set out to assemble a team solely of women of color—it just happened. “We did set out intentionally to assemble an outstanding team of inspiring designers,” he said.

That team includes, along with Crespo, scenic designer Shoko Kambara, costume designer Lux Haac, lighting designer Dawn Chiang, and sound designer Elisheba Ittoop. “I personally love working on all-female teams,” Crespo enthused. “I don’t know why, but the communication’s easier for some reason. We all come to each other with greater respect and understanding and collaboration.”

Native Gardens is a 90-minute one-act (split into two acts for this production) that follows two sets of couples who live beside each other in a lush, historic D.C. neighborhood. Frank and Virginia Butley are an elderly white couple whose son has aged and moved out of the house they’ve lived in for decades. Frank spends most of his free time perfecting his manicured garden, a pastime he hopes will relieve his chronic stress and win him an award from the Potomac Horticultural Society.

New next door are Tania and Pablo Del Valle, a Latinx couple in their early 30s. They’re expecting their first child and have big plans for their fixer-upper, including a “native garden” made of plants indigenous to the environment. The idea is the brainchild of Tania, a Ph.D. candidate in the thick of identity experiments for her doctoral dissertation in anthropology. As she explains in the play, “I am interested in origins, and when we claim them and when we stop.” Pablo is a lawyer with dreams of making partner at his new firm—an ambition that gives him the idea of inviting his entire 60-person firm to their not-yet-fixed-up fixer upper.

That’s where the fence comes in.

With Frank and Virginia’s blessing, Tania and Pablo plan to replace the run-down chain-link fence that separates the two yards with “the kind of stately wood fence a law firm would appreciate,” as Pablo puts it. But after examining the plan for their yard, the Del Valles discover they’re entitled to more space than currently demarcated—two feet, to be precise. But moving the fence to claim those two feet promises to ruin Frank’s garden just days before his competition, while keeping it where it is robs the Del Valles of their rightful property.

The ensuing fight over the fence’s true location is riddled with racism, ageism, microaggressions, and questions of who can (and should) claim ownership of land. Some lines read like they’re ripped from the headlines (and they are).

Declares Tania to Frank and Virginia: “I’m building my fence to keep you out!”

Adds Pablo, “And you’re going to pay for it.”

The seed for Native Gardens was planted at a dinner party. Zacarías was looking for ideas for a play she was writing for Cincinnati Playhouse in the Park, and a friend told her, “kind of jokingly, ‘Oh, you should write about me, I’m in a fight with my neighbors,’” Zacarías recalled. As the friend described the fight, other party guests chimed in with their own tales of neighborhood squabbles. The stories were both “absurd” and “really stressful,” she said.

While the stories were told with laughter, they stuck with the playwright. “All of those fights are so primal and poetic and absurd in some ways,” Zacarías said. “But the consequences were really real and emotionally upsetting. And I kept thinking, Wow, it’s almost like every single battle between nations or tribes, etc., boils down to this fight about property and culture, in a sense.”

The play also gave Zacarías a platform for creating Latinx characters who are seldom seen onstage. “I was over the moon about the fact that I got to play a smart, passionate Latina who was very educated and I didn’t have to put an accent on for,” said Summers Gonzalez, who plays Tania.

It also could hardly be better timed. Though Zacarías wrote the play long before Donald Trump even began talking about building a wall, obviously, she said, “There’s been something in the atmosphere for much longer that made this comedy about gardening and planting and building a fence have a much deeper resonance.”

Since the play premiered at Cincinnatti Playhouse in January 2016, Zacarías has peppered the script with details that deepened its connection to current events, particularly as Trump’s wall entered the national conversation and the piece grew and moved on to larger productions. (That’s where the “you’ll pay for it” line came from.) The text is now in its final, ready-to-publish form.

Native Gardens drew Hupp’s attention in January 2018 as he programmed the next season. The play addressed “issues that our season wasn’t confronting that I wanted us to talk about,” he said. No one involved knew that the president’s demand for a wall would effectively shut down the government by year’s end. But of course, as in real life, a wall is not just a wall; it’s also a metaphor for fear of the unknown, for cultural differences, and for the toxicity of divisions. Though unlike in real life, the play is actually intentionally funny.

Months before the cast was assembled, in August 2018, Syracuse Stage brought the Native Gardens design team together. The theatre organized a design conference, providing two days of meetings for each designer to share their vision of the play.

“It’s such an important part of the process, where we get to just be in a room together and dream up the show and then start putting the logistics on it,” Elisheba Ittoop said.

It was then that Crespo discovered that in addition to doing sound design, Ittoop composes music, and asked her to craft music for the scenic transitions. Many of the transitions contain short vignettes in which the neighbors quietly stir the pot—such as throwing acorns from one yard to the other—or the Latinx gardeners bring in some plants, take others out, or bring in supplies to build the wood fence. Ittoop tends to compose original music for shows she works on to help defray the costs of pre-recorded music. It also gives her the flexibility to cut or manipulate the music in any way needed.

“I do care about artists getting fairly compensated for their music,” she said. “I’m less and less interested in putting up music that’s not paid for, that we haven’t gotten the rights for. And I’m more interested in creating, crafting something that’s specifically for our show.”

Crespo and Ittoop worked together to translate each character musically. For the aging Butleys, they chose an elegant and classical sound. Ittoop described this music to the theatre’s marketing team as “a little bit of a raised eyebrow,” drawing inspiration from Mark Mothersbaugh’s score for The Royal Tenenbaums.

For the young, vibrant Del Valles, Ittoop steered clear of the obvious choice of using Latin music to characterize a Latinx couple. “That’s not really interesting to me, and I think that also goes in to stereotypes really quickly,” she said. Instead, Ittoop focused on the feeling of disruption that comes along with the Del Valles’ presence. A marching band, she and Crespo determined, would evoke this mood, citing the way the CW television show “Jane the Virgin” uses a marching band for many of its musical transitions. Ittoop also drew inspiration from the theme of NBC’s “Parks and Recreation.”

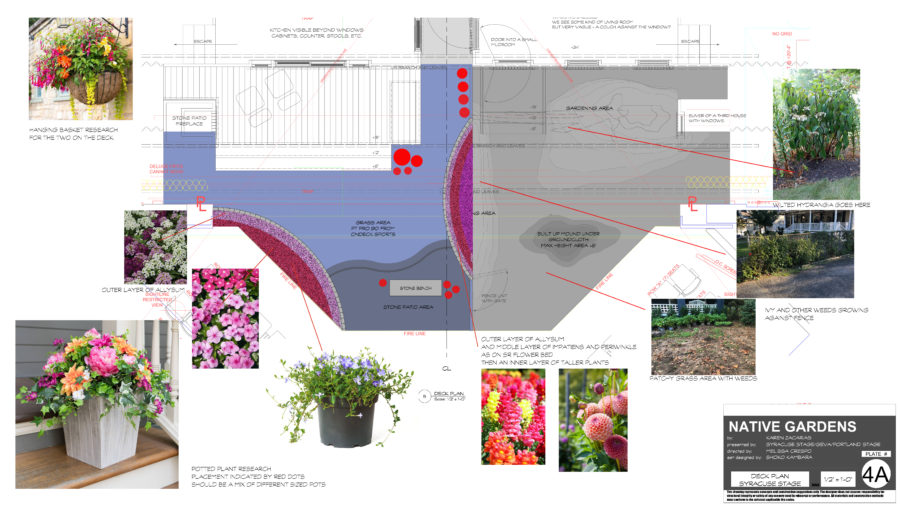

Hints for Shoko Kambara’s scenic design appear to be embedded in the text: Tania and Pablo refer to their “patched grass,” a gnome, and a majestic oak tree, among other items, giving Kambara a vision of how their yard should appear. “It’s like reading a murder mystery where you have to collect the clues,” Kambara said.

After researching neighborhoods in Washington, D.C., Kambara settled on row houses for each couple. The Butleys’ home was modern and renovated, complete with a back deck, while the Del Valles’ appeared to have not seen attention in years. Kambara created two houses very similar in design, as though the Del Valle house is what the Butleys’ would look like prior to renovation. “Probably, in that neighborhood, they’re all the same, and then everyone adds their little flavor to it,” Kambara said. While much of the material for the Butleys’ house could be found online, the Del Valles’ had to be custom-made to appear old and run-down.

And then there’s Frank’s garden. While Crespo and Kambara researched many of the flowers mentioned in the play, finding the silk form of all the flowers for Frank’s garden was too costly, so they focused more on the color palette than the actual type of flower. “I tried to keep the larger flower beds in a tighter color palette, so it wasn’t too distracting,” Kambara said. “I didn’t want it to look like a birthday cake, like confetti.”

A special custom mixture of fake dirt was concocted by the props department to avoid the bugs and mud that real dirt would bring. A dry mixture of coconut fiber substrate, dark ground cork, buckwheat hulls, and light ground cork, it was mixed together and combined with corn starch, soap, and water. “I actually garden myself, so when I tested it I was like, ‘This is what my hands look like when I dig in my garden,” prop supervisor Mary Houston explained.

At each performance, flowers get yanked and portions of the garden are torn up. So Kambara designated specific flowers—complete with fake roots and dirt—that could be pulled out. Actors were instructed which parts of the garden they could destroy, and which had to remain intact. “Part of the trick is to make Frank’s yard so tightly designed that even a little shift in it will [cause disruption],” Kambara said.

She was also tasked with creating a set that could not only travel but fit inside a few different theatres. “It’s designed for three spaces, and we slightly shift the downstage area in each venue,” Kambara said. “But it’s almost the same.”

A significant element of Kambara’s scenery was the towering oak tree, requiring close collaboration with lighting designer Dawn Chiang to ensure the foliage didn’t get in the way of the lighting instruments. After working with Syracuse Stage’s technical director Randall Steffen, Kambara and Chiang were able to get the leaves high enough to allow for light to seep through.

Chiang’s lighting bounces between daytime, nighttime, and short vignettes performed during transitions. And it varies slightly with each theatre, due to differences in equipment. Chiang and Ittoop are the only members of the design team who are going to each theatre to help ready the show. “Because [lighting instruments are] so unique to every venue that you go to, I have to go because I have to reposition everything and re-cue everything,” Chiang said. Crespo will also travel to Rochester and Portland to direct each city’s new batch of gardeners.

Color played an integral role in how costumer designer Lux Haac helped tell the play’s story. “The thing that was important to Melissa and I when we started this was just really making sure that these were real people and that they came across as very genuine, and that that came through in the costumes,” Haac said.

Not unlike their theme music, the refined lifestyle of the Butleys was also reflected through color. “The Butleys’ garden is much more traditional, which led to their costumes being more conservative,” Haac explained.

Haac’s inspiration also came from the characters’ relationships to their gardens. For Tania, she used a vibrant, vivid color palette that reflected Tania’s high energy and the new life she’s starting with Pablo. “She is dressing for the garden she aspires to have,” Haac said. She dressed the Butleys in a more subdued palette that contrasted with their colorful garden.

Despite all the pronounced conflicts among these characters, reflected in the show’s design, Crespo stressed to the whole team the importance of conveying that the characters all like each other and take every action with good intentions. This is key during the couples’ first meeting, where, “in the wrong hands, the beginning of the play can really go south very quickly,” Crespo said.

Summers Gonzalez admits that, in the early stages of rehearsal, she was working too hard to communicate that Tania did not agree with the Butleys. Instead of instilling Tania with nuance, she came across as somewhat of a know-it-all. She knew she needed to make an adjustment to align with Crespo’s vision and the intent of the play.

“All of these characters are good human beings,” Summers Gonzalez said. “You can be a really great person and not necessarily agree with how someone lives their life, but that doesn’t mean that you need to make that apparent.”

This is evident in the character descriptions that Zacarías provides in the beginning of the script, which begin the same way for every character: “Smart, likeable.” There are no easy villains here.

“All of these characters, they want to do the best they can and no one wants to offend the other,” Gonzalez said. “Everyone wants to get along.” And unlike in real life, both parties are willing to work together and compromise to reach a happy ending.

Native Gardens met its budgeted sales goal for its Syracuse run by Feb. 13, the first day of previews and two days before the play officially opened at the 499-seat Archbold Theatre. “That is a relatively unheard-of statistic for us, for a play to achieve its full goal before opening night,” Hupp said. To him, the box office numbers indicate “a desire to confront these issues.”

This desire was reflected in the play’s reviews, which were overwhelmingly positive. In a review for the city’s local news site, Syracuse.com, Linda Lowen called the comedy “an upbeat workout of the funny bone, releasing the sort of toxins we’d all be better off without.” It was not lost on Lowen that it was a work from a design team entirely of women of color. “What happens onstage isn’t the only political statement being made by Native Gardens,” she wrote.

Native Gardens’s official opening on Feb. 15 landed on the day Trump declared a national emergency to access the funds he says he needs to build his wall. “It felt very eerie,” Crespo said of the play’s timing with current events. At the same time, as she listened to audiences laugh and react around her, she realized, “It’s good that the play is there for people to have an outlet to talk about it.”

But it wasn’t just laughter that stuck with Summers Gonzalez. After one performance, she recalled, a Latina audience member began to cry while speaking to her. “She was like, ‘You don’t know how much it means to see someone like me onstage,’” Gonzalez recalled. To which she responded: “I’m right there with you.”

Maggie Gilroy, a former intern of this magazine, is a news reporter for The Press & Sun-Bulletin in Binghamton, N.Y. In 2015 she interned for Syracuse Stage’s dramaturgy dept.

Native Gardens is written by Karen Zacarías. It first ran at Syracuse Stage Feb. 13-March 3, and is running Geva Theatre Center in Rochester, New York March 26-April 21, and Portland Center Stage May 18-June 16. It is directed by Melissa Crespo, with scenic design by Shoko Kambara, costume design by Lux Haac, lighting design by Dawn Chiang, and sound design/original music by Elisheba Ittoop.