A sci-fi musical. A pop show inspired by an ancient story. An Alice in Wonderland with music. A blues-infused jukebox show. A stage adaptation of a wildly popular musical film.

Quick, name the year those musicals hit the boards. Is it 1982, when Little Shop of Horrors, Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat, Alice in Wonderland, Blues in the Night, and Seven Brides for Seven Brothers opened on and Off-Broadway?

Could be—but it also sounds a lot like 2019. This, after all, is the season that includes Be More Chill, Hadestown, Alice by Heart, Ain’t Too Proud, and Moulin Rouge!. We can still describe the latest wave of musicals, it seems, the way we did more than 30 years ago. So how far exactly has the musical landscape and the form itself progressed in those decades?

Musicals have had “I want” songs and “11 o’clock” numbers since the days of Gilbert and Sullivan, and out-of-town tryouts, developmental workshops, and producer/writer partnerships have always been crucial to the writing process. But changes are afoot. The biggest of these changes comes, ironically, not from developments onstage but in film. The American musical has found its way back into the mainstream zeitgeist via such films as The Greatest Showman and Mary Poppins Returns.

In tandem with that on-screen renaissance, cast recordings for Hamilton and Dear Evan Hansen are hitting the Billboard Top 20, marking the first time in 54 years—since Hello, Dolly! and Fiddler on the Roof—that two stage-born albums were in the Top 20.

“It’s a new golden age of musical theatre,” says Preston Whiteway, executive director of the Eugene O’Neill Theater Center in Waterford, Conn., which has seen an uptick in the number of musicals submitted to be part of its development program.

The breadth of topics that are viable for musicalization has also expanded, particularly recently, with more chamber-like works such as The Band’s Visit, Dear Evan Hansen, and Fun Home being rewarded for their adventurousness with the Tony Awards’ top prize.

“The most amazing thing in my theatre-producing lifetime—even in my theatregoing lifetime—is the broad variety of different things that are now dealt with in musical theatre,” says producer Jack Viertel, who is credited with the initial concept for The Prom, which opened on Broadway last fall. While that show harks back to the big, broad musical comedies of earlier days, it also boldly tackles topical and complicated issues, including high school bullying and anti-LGBTQ prejudice. “It’s a contemporary story being told in a more traditional way, and it’s those two things combined that make it so interesting,” says Matthew Sklar, who wrote the show’s music.

Jennifer Ashley Tepper, a producer of the sci-fi show Be More Chill, which opened on Broadway in March, calls the trend “musical plays”—i.e., pieces that cover serious and controversial topics with music added. Not that there aren’t classic precedents for this, as Tepper—a self-styled Broadway historian—is quick to note. “The difficult-subject-matter thing is really a descendant of the Sondheim/Prince musicals,” she says. “Pacific Overtures and Company pointed the way so that musicals could be more topical.” (She might have cited far earlier examples, dating through South Pacific all the way back to the antiracism of Show Boat in 1927.)

Michael R. Jackson says he also looked to Sondheim, particularly Company, when crafting his self-referential meta-musical musical A Strange Loop, which premieres at New York City’s Playwrights Horizons in association with Page 73 in May. The show follows a Black queer musical theatre writer, working on a show about a Black queer musical-theatre writer, working on a show about…you get the point. “I wanted A Strange Loop to be a proper musical, but I also knew it was probably going to be what used to be called a ‘concept musical,’” Jackson says of the nonlinear story. “The challenge became to figure out: What is the form of this? How much of a book is there? What are the other characters, and how do they operate? It is about a character examining his own life in the moment.”

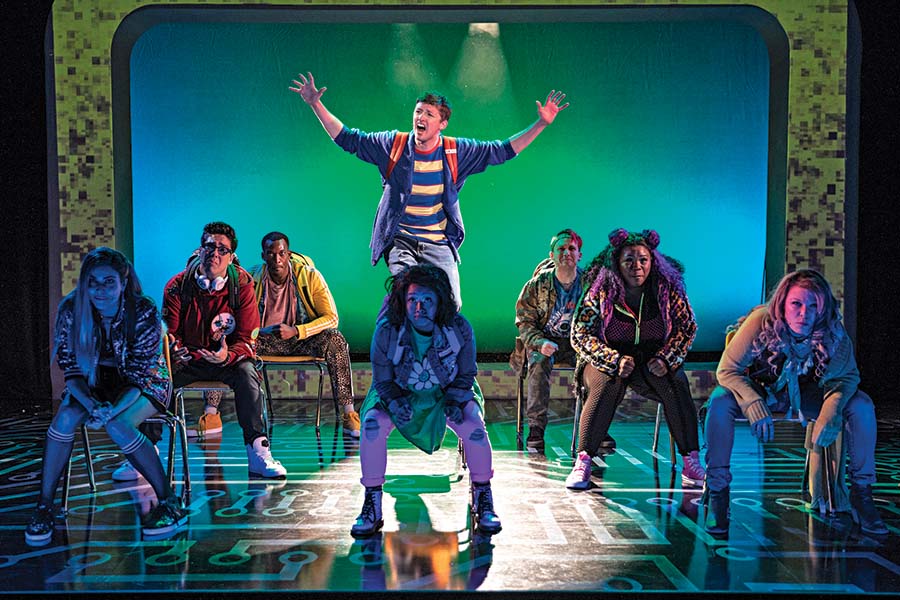

While the pop-infused score for Joe Iconis’s Be More Chill sounds very contemporary, Iconis says his musical—based on Ned Vizzini’s book about a high schooler so desperate to be cool he swallows a super-computer called a “squip” that tells him what to do—has antecedents in such classics as Damn Yankees and Little Shop of Horrors. That’s only to be expected, given that Iconis listened to nothing but cast albums until college.

“For me the idea of what good writing is is rooted in classic musical theatre—it’s just what feels correct and what makes sense,” he says. That said, he continues, “Be More Chill is very style-forward. It’s written with a nod to 1950s sci-fi movies and 1970s horror films, and to today’s pop music that feels very ‘synth-y’ and in-your-face. We call it a ‘maximalist pop fantasia.’”

On the other hand, singer-songwriter Anaïs Mitchell felt relatively isolated artistically as she composed her first stage musical, Hadestown, which opens on Broadway in April after a recent run at Britain’s National Theatre and a production at New York Theatre Workshop in 2016. Mitchell, who had begun a low-residency MFA program with a focus on musical theatre (unfinished to date) while writing Hadestown, says she felt a bit like an outsider to the theatre community—and she took strength from that feeling.

“A song, for me, is a circle,” she explains. “The verses and choruses circle back on themselves; there’s a suspension of time which is very mystical. How to hold together these circles and lines is the thing,” she says of the way these self-contained creations live within a theatrical story. Her show, she concludes, “is just always going to be a different animal from most shows.”

Luckily Mitchell shared the journey with her director, Rachel Chavkin. The two met in 2012 after Chavkin helmed another form-breaking, forward-thinking musical, Natasha, Pierre & the Great Comet of 1812, and began working together on Hadestown soon after. Chavkin, though steeped in theatre via her company the TEAM and no longer a stranger to musicals thanks to her work with composer Dave Malloy, including Great Comet, still counts herself a musical theatre newbie, mentioning she only recently saw Wicked for the first time.

“No single piece can be met with the same set of tools” as any other, Chavkin asserts. “There are obviously basic tools of leadership that transfer over, like a sense of innovation that I presume every director feels.”

As newcomers like Mitchell continue to make their marks on the musical, the success of Sara Bareilles’s Waitress has led other pop writers to Broadway, from Eddie Perfect, who penned songs for King Kong and Beetlejuice, to Bryan Adams and Jim Vallance, who wrote the songs for Pretty Woman. This trend worries Lucas Tahiruzzaman Syed, co-editor of the new yearly periodical Musical Theater Today, and himself a composer with a background in the concert world. While the influx of pop writers without musical training may broaden the possibilities of the form, might it also limit options for emerging writers, like Syed, who are dedicated primarily to the form?

“There are artists being invited into the fold for reasons that are often super valid, and they often produce really great work, but they are not tried-and-true musical theatre writers,” says Syed, who is part of the BMI Lehman Engel Musical Theatre Workshop, which along with NYU’s Graduate Musical Theatre Writing program, is among the few programs centering on the craft of writing musicals.

Kathy Evans, who is founder and executive director of the upstate New York Rhinebeck Writers Retreat and served as executive director of the National Alliance for Musical Theatre for nine years, also has a finger on the pulse of the field, and she sees the glass as more than half full.

“What’s been exciting to me is to just see how much the field has grown,” Evans enthuses, noting that her applications have tripled since she founded the Rhinebeck program in 2011, and that the number of theatres looking for musicals to produce has expanded. This demand means there may be room for all of the above—pop writers new to musicals, as well as dedicated musical theatre pros.

Another infusion of material comes courtesy of jukebox musicals, an ongoing trend with no end in sight; this year’s crowded slate, including The Cher Show and Head Over Heels, joins such long-running bio-musicals as Beautiful and Jersey Boys; Tina, based on the life of Tina Turner, now in the West End and eyeing Broadway; and the Temptations musical Ain’t Too Proud, which opened in March. While the songs in these shows by definition aren’t written for theatre, the books are, and this is another route by which new talent infuses the form. Dominique Morisseau penned the book for Ain’t Too Proud, joining such old hands as longtime musical theatre librettists Terrence McNally and Marsha Norman as well as newcomers like Steven Levenson (Dear Evan Hansen) and Lisa Kron (Fun Home).

“My hopeful prediction is that it will really push story forward,” Morisseau says about the surge of playwrights working in musicals. But story in a musical doesn’t necessarily come via dialogue, as Morisseau learned. “Just dealing with the scarcity of language in a musical was unique to me—I’m a very dense writer,” said the author of Pipeline and Skeleton Crew. “I can write you a whole monologue, and suddenly it’s like, ‘Oh, no, wait—the song has to be the monologue!’”

Ain’t Too Proud began its journey to Broadway at D.C.’s Kennedy Center in June 2018 and at the Ahmanson Theatre at L.A.’s Center Theatre Group that September. Most other Broadway-aimed tuners make their starts Off-Broadway or outside NYC. American Repertory Theater of Cambridge, Mass., is producing the new musical We Live in Cairo (May 14-June 16), while Paradise Square played at the Bay Area’s Berkeley Repertory Theatre earlier this year; Marie, Dancing Still is at Seattle’s 5th Avenue Theatre through April 14; and Benny & Joon is at Millburn, N.J.’s Paper Mill Playhouse through May 5, after an earlier run at the Old Globe in San Diego.

With the opening of its new uptown space, NYC’s MCC Theater has launched a new-musical development program called SongLabs, and has programmed the musical Alice By Heart (which runs through April 7), its fourth ever, penned by Spring Awakening scribes Duncan Sheik and Steven Sater. Tom Kitt and John Logan’s Superhero concluded its Off-Broadway run at Second Stage in March, and another Manhattan troupe, Atlantic Theater Company, has The Secret Life of Bees opening in May.

This last company’s Broadway track record is two for two (with best-musical Tony winners, Spring Awakening in 2007 and The Band’s Visit in 2018). Atlantic artistic director Neil Pepe says the company’s transition from ensemble-driven work on plays to new musicals was organic. He also notes that costs are lower Off-Broadway, and that almost all the company’s musicals have had funding from a commercial-enhancement producer. “From a philosophical mission point of view, the most important thing is that the artist and the piece are allowed to breathe and grow on their own terms,” Pepe says.

Both A Strange Loop’s Jackson and Ain’t Too Proud’s Morisseau stress the importance of diverse voices and writers entering the field, as both gender parity and racial diversity have been sorely lacking in the field historically, and right up to the present. Jackson made sure the actors who populate his cast all identify as Black and queer, and Morisseau hopefully cites a few Black female colleagues working in the form, including Lynn Nottage (The Secret Life of Bees, as well as the stalled Michael Jackson jukebox musical Don’t Stop ’Til You Get Enough) and Katori Hall (one of the writers of Tina). There’s also Kirsten Childs, whose Bella: An American Tall Tale received a co-world premiere at Playwrights Horizons and Dallas Theater Center in 2017.

Musicals written by more diverse voices are particularly important for young people, as shows that do manage to make it to Broadway are usually directly minted into the repertoire and go on to be produced at community theatres and high schools, giving young people roles they can see themselves in.

Young people have also become tastemakers in a tangible way with the advent of social media, via Tumblr, YouTube, and Instagram (plus other digital platforms this non-teen writer probably doesn’t know about). Be More Chill is Exhibit A: It premiered at Red Bank, N.J.’s Two River Theater to mixed reviews in 2015, then fell out of the pipeline until Ghostlight Records released a cast album. Music videos went viral on YouTube, spawning a Tumblr following among young fans rivaling that of Hamilton, launching the album onto the iTunes charts, and spawning a spate of fan art and fan videos. These consumers of the show later converted into sold-out, screaming audiences for last year’s Off-Broadway run, leading to the current Broadway staging. The question now: whether these fans are in the Broadway ticket-buying demographic. How will the show fare at those prices?

Tepper points to Rent as a forebear, as a similar gateway musical, noting that the excitement from youth often spreads up to other age brackets. (She’s even sent some Be More Chill fans home to listen to Rent to expand their musical knowledge.) “It’s like Elvis. It’s like the Beatles. The mainstream hits of art are often first seen in their importance by young people,” Tepper says. In fact, the 2017-18 Broadway season saw a record level of attendance from children and teens, according to the Broadway League’s annual survey.

But as the form’s fortunes rise, so does the scarcity of real estate on Broadway. “It’s more difficult now than it’s ever been, for a number of reasons,” reports Viertel, who serves as senior vice president at Jujamcyn Theatres. “We have approximately 40 theatres on Broadway, but the actual buildings that you can put a show into keeps shrinking” as long runs proliferate. “There’s more capital for producing, so there are many more shows being developed that are looking for a theatre—it’s becoming harder and harder, and there’s no solution in sight,” he says.

While that situation can lead to theatre owners being risk-averse—opting for known quantities and brands rather than untested authors—the current Broadway season is encouragingly full of writing teams making their Main Stem debuts. That so many new voices are still entering the landscape is a harbinger of the musical’s new vitality. Years after Hamilton, Fun Home, and Dear Evan Hansen raised the bar for the form, the American musical is still singing out strong.

“I always imagined we were too far out of the box, stylistically, to have a home on Broadway,” confesses Hadestown’s Mitchell. “But, you know, it’s thrilling to see Broadway embracing a lot of different sounds these days—Hamilton, Great Comet. Theatres and audiences are hungry for out-of-the-box approaches to musical storytelling.”

Suzy Evans is a former senior editor of this magazine.

CORRECTIONS: An earlier version of this article misspelled Matthew Sklar’s last name; it’s Sklar, not Skylar. Also, Jennifer Ashley Tepper is the producer of Be More Chill, not the show’s lead producer; Be More Chill marks Tepper’s second producing project on Broadway.