There I was again: gazing into a tidy, modest Southern California bungalow, an outpost of 1970s exurbia adorned with Formica cabinets and ferns in hanging pots. And there they were again: the two brothers. One a preppy, studious writer, the other a thieving renegade. And between them a hostile wariness that would devolve into a clawing, choking, thrashing floor fight and a trashed kitchen. Not to mention the murder of a manual typewriter by golf club.

This time the battling siblings in True West were portrayed by two new theatrical adversaries: Paul Dano (star of the Brian Wilson biopic Love and Mercy, among other movies) was the anxious Hollywood screenwriter Austin. And a bearded, weathered Ethan Hawke (recently a troubled priest in the film First Reformed), grubby and contemptuous as the older outlaw brother Lee.

I can’t give the exact number, but watching these two go at it in the Roundabout Theatre’s True West at American Airlines Theatre (the production runs through March 17) was at least my fifth viewing this seminal Sam Shepard play. My first was the white-hot world premiere in 1980, directed by Robert Woodruff at Magic Theatre in San Francisco, when Shepard was playwright-in-residence there.

So what draws me again and again into this heart-of-darkness tale steeped in male angst and brotherly hate? A play that takes place in a zone without, so to speak, the civilizing influence of women? And what makes True West a kind of modern rite of theatrical passage, a proving ground for successive teams of ambitious male thespians, from Steppenwolf’s Gary Sinise and John Malkovich (in the 1980s) to Philip Seymour Hoffman and John C. Reilly, switching roles during a Broadway run (in 2000), even to Bruce Willis and Chad Jones (in a 2002 Idaho production filmed for Showtime)? This year’s contenders also include Kit Harington from “Game of Thrones” and actor-musician Johnny Flynn, now wrapping up a West End run across the pond.

If it seems I’m addicted to theatrical testosterone, let me note that I’m thankful and heartened that female dramatists are finally getting more opportunities to explore the complexities of sisterhood and womanhood onstage. It’s about time. But I can’t write True West off as merely a retro exercise in machismo—because it isn’t. It continues to reveal and illuminate by torchlight, by hibachi flames (as indicated in the script), meaningful shivers and shadows, reflections and portents I hadn’t noticed in the first, or fourth, time around. The play remains an imperfect tour de force in its brutal candor about the mixed messages our culture sends to men, and the way these continue to shape and constrain male identity, as well as American family and political dynamics.

While TV and movie dramas too often still rely on blazing male violence at its deadliest and the jocular male bonding loosely tagged as “bromance,” the warring dualities of American masculinity which Shepard (who died in 2017) had a bone-deep understanding of are rarely captured as openly and scarily as in True West. It’s no wonder that successive generations of actors are drawn to the roles of Lee and Austin, and their leery, raucous duet.

The play’s set-up is simplistic: The straight-arrow, college-educated screenwriter Austin and his prodigal outlaw brother Lee, estranged for years, come together in their mother’s house at the edge of a California desert. Austin, house-sitting while Mom’s away, is writing a film script, and Lee turns up to distract, bait, and terrorize his younger sibling. Their mutual antipathy obviously courts comparison with the biblical Cain-and-Abel story, as well the internal battle between consciousness and what psychoanalytic theorist C.G. Jung called “the shadow self.” According to Jung, “Everyone carries a shadow, and the less it is embodied in the individual’s conscious life, the blacker and denser it is.”

This is obviously a theme circulating through a lot of male-centric drama and fiction. Yet it isn’t just a Jekyll-vs.-Hyde spectacle of opposite natures clashing here. Nor is it exactly autobiography (though, among other parallels with his own life, Shepard did spend part of his youth where the play is set, about 40 miles from Los Angeles). In the second act the siblings effectively trade places, merge, then split off again, winding up as primal adversaries but no longer opposites. “I wanted to write a play about double nature,” Shepard told Robert Coe in The New York Times, “one that wouldn’t be symbolic or metaphorical or any of that stuff…I think we’re split in a much more devastating way than psychology can ever reveal.”

Live theatre can reveal in flashes what textbook psychology cannot. And True West is live theatre on steroids, with blazing klieg lights, in James MacDonald’s staging for Roundabout, framing each scene. I don’t know of another modern American play that delves so intimately into the dangerously conflicted and enduring notions of brotherhood in relation to the myths of the American West. There are some clunky devices here and there, but four decades after its premiere True West still has such lacerating humor, such heat, such ambivalence over what it means to be a man in a land brutally stripped of its Indigenous population, over-developed yet still haunted by the howls of coyotes, the chatter of crickets, the Old West iconography of Hollywood films. It has been part of our politics too: the Marlboro Man image of Reagan on horseback, or George W. Bush clearing brush on his Texas spread. But when the bully squares off against the gentleman they are both taken down.

Another reason True West is able to lasso so many leading actors? It’s one of Shepard’s funniest plays, spiked with comic relief after the heavy darkness of the two previous entries in the author’s “family trilogy”: the American Gothic tour of hell in Buried Child, which followed the freakish, hallucinatory domesticity of The Curse of the Starving Class. More than anything, though, the brothers in True West are juicy roles, laced with many physical and psychic demands, including a hilarious orgy of toast-making after one brother steals a dozen or so toasters from the neighborhood on a dare. (In a San Francisco production, one toaster caught fire and Ebbe Roe Smith, as Austin, handily put it out with a dishtowel without missing a scripted beat.)

The text is trip-wired to detonate quietly at first, then work up to a blast of open warfare, broken finally by the appearance of the only female character, a mother (called only “Mom” in the script, and played in the Roundabout version by Marylouise Burke). She is dazed, perplexed by the spectacle of her sons reverting to childhood rivalry in her prim home. Urging her “boys” to “take it outside” as Austin nearly strangles Lee to death, she injects notes of perplexity and conventional normality. Shepard would later craft more dimensional, contoured female roles in Fool for Love and Lie of the Mind, but he at least grants Mom a frisson of existential dread as she muses on her trip to America’s final frontier, Alaska. “It was the worst feeling being up there,” she tells her sons. “In Alaska. Staring out a window. I never felt so desperate before.”

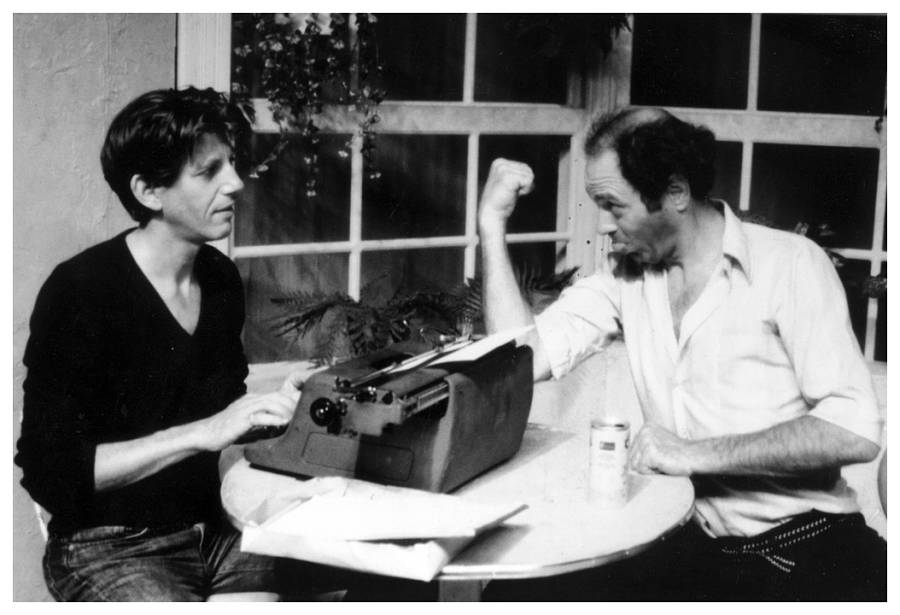

How does the new production stack up? It is all about the acting, and the chemistry. Jim Haynie’s volatile portrayal of Lee, opposite Peter Coyote’s Austin, in Woodruff’s galvanic original staging (Woodruff also directed the world premiere of Buried Child and the U.S. debut of Curse of the Starving Class), burns most brightly in my memory. Perhaps unfairly, every other Lee I’ve seen gets measured against Haynie’s. A big man, drinking hard and hulking over Coyote’s Austin as he tried in vain to work at the typewriter, Haynie was a primitive id oozing menace from every sweaty pore—but a cunning one with pathetic dreams of glory. When a vapid Hollywood film producer showed up to meet with Austin, this Lee didn’t so much convince the jive schnook he had a better idea for a movie than his brother. No, snaring him into a golf bet, Lee scared him, gangster-style, into making good on the wager and optioning his screenplay—one Lee couldn’t write alone, of course, because an unruly id can barely function without a reality-based ego.

The notion that this barely literate desert rat could just trade places with his more articulate and presentable brother, and manage this coup by beating a studio bigwig at golf, is blatantly absurd—a little jolt of surrealism that’s vintage Shepard. But when Haynie eventually crumpled to reveal Lee’s psychic damage and bleak isolation, it felt all too real.

Some of the play’s most emotionally salient moments in every production occur as Lee and Austin quietly talk about their father, “the old man” who caught the desert fever that’s both romanticized and refuted in the play. (The old man figure appears in many Shepard dramas; he’s clearly based on the writer’s own parent, Samuel Shepard Rogers, an abusive alcoholic who left a deep imprint on his son’s character and dramaturgy.) The old man has been holed up for years, boozing and becoming (literally and figuratively)toothless: losing his real teeth to decay, and his false set in a pile of chop suey. (Austin’s monologue about it is based on a true incident.) When the brothers’ mother returns earlier than expected and asks her desert-bound sons, “You gonna go live with your father?” Lee answers: “No. We’re going to a different desert.” But how different could it be?

On Broadway now Hawke, like Malkovich in the famed Steppenwolf staging (you can find the televised version in segments on YouTube), is particularly adept at Lee’s pitiless needling and baiting of Paul Dano’s initially guarded Austin. Swilling beers, parading around in a grimy T-shirt that looks like a Stanley Kowalski hand-me-down, angling to borrow a car so he can case nearby homes to rob, Hawke exploits every opportunity to take Austin down a few pegs. And in the trigger moment when Austin offers pity and a handout, Hawke’s barely repressed rage erupts. Lee’s manhood is tied up in being a desperado, not a desperate charity case. He’s also a wannabe artist who can’t articulate the movie plot rattling around in his brain—without, pointedly, the help of his conscious self: his brother.

Austin has always been the more challenging role in this blood knot. Coyote and Sinise barely hid their irritation and disdain for the belligerent, uncouth Lee. (At one point, while Sinise scrupulously waters the mother’s prize ferns, Malkovich causally picks his nose.) Opposite Hawke, Dano comes on as more placid, less condescending and disapproving. Some critics have considered this a deficit, a seeming passivity that tilts the play too far in the flashier Hawke’s direction.

But I liked that Dano found a fresh approach to Austin. As he learns that Hollywood might prefer Lee’s rough, nonsensical action film scenario to his own considered “period piece,” he becomes sharper, edgier. The “safe” identity Austin thought he’d achieved—a bourgeois existence with a family, a successful career—starts to disintegrate. By the time he gets roaring drunk and almost pitiful in his eagerness to light out for the desert with Lee, Austin’s descent into the wilderness is steeper in this production than in any other True West I’ve seen.

I don’t believe Shepard was endorsing either Lee’s lawlessness, or Austin’s rejection-then-embrace of it, in True West. In a play that can still give you the willies, he was portraying impressionistically, but not resolving, the smack-down between the poet and the savage, the self-made man and the chip off the old block. In an interview in American Theatre, Shepard said the play “doesn’t really have an ending; it has a confrontation. A resolution isn’t an ending; it’s a strangulation.”

Seattle-based critic and author Misha Berson writes frequently for this magazine.

The Roundabout Theatre’s production of True West is directed by James Macdonald, with sets by Mimi Lien, costumes by Kate Voyce, lighting by Jane Cox, original music and sound design by Bray Poor, hair and wig design by Tom Watson, dialect consulting by Kate Wilson, fight choreography by Thomas Schall, and production stage management by James Latus.