Representation and awareness go hand in hand. It’s simple math: The more representation of a group in the arts, the more aware the wider culture becomes of that group’s culture. But an upward tick in representation doesn’t change the demographics. There aren’t suddenly more Asian Americans, say, because of Crazy Rich Asians, and Black Panther didn’t increase the Black population in this country either.

So rather than saying there’s a new wave of Black playwrights sweeping the nation, it’s better to say that U.S. theatres are at last waking up to the many writers already out there doing important work. These include, to list just a few of the most prominent names, Branden Jacobs-Jenkins (An Octoroon, Gloria), Dominique Morisseau (Pipeline, Skeleton Crew), Jeremy O. Harris (Slave Play, Daddy), Danai Gurira (Eclipsed, Familiar), Mfoniso Udofia (Sojourners, Her Portmanteau), Aleshea Harris (Is God Is, What to Send Up When It Goes Down), Ngozi Anyanwu (Good Grief, The Homecoming Queen), James Ijames (Kill Move Paradise, White), Ike Holter (Rightlynd, Exit Strategy), Antoinette Nwandu (Pass Over), Marcus Gardley (The House That Will Not Stand), Katori Hall (The Mountaintop, Our Lady of Kibeho), Donja R. Love (Fireflies), Jackie Sibblies Drury (We Are Proud to Present…, Fairview), and Tarell Alvin McCraney (The Brother/Sister Plays, Choir Boy). And that’s not counting a few veterans still working at the top of their form, including Lynn Nottage, Suzan-Lori Parks, Anna Deavere Smith, Robert O’Hara, Dael Orlandersmith, and Pearl Cleage, among others.

Some have been on the scene for decades, others are just out of college and have quickly burst into prominence. But none consider themselves pioneers: Indeed today’s Black playwrights don’t look back on their predecessors and see fewer or lesser. Instead they see a lineage of antecedents who never got their due and who fought for the representation we’re starting to finally see now. Holter perhaps puts it best when he says, “We’ve always existed. It’s just that our stories weren’t listened to. We were kind of denied that.”

It was once popularly thought that Black playwrights were rare or uncommon, a myth that Holter described as a “unicorn syndrome.” It was a myth not limited to white theatremakers. Holter admits that as he came up—and his is not an uncommon story—he spent a long time not knowing about the breadth and depth of Black playwriting, because for the most part all that was taught was August Wilson.

“I think people stop—they’re like, ‘Oh, I know my one woman playwright, Caryl Churchill. I’m good,’” says Holter. “Or ‘I know my one Asian playwright, and I know my one Latina playwright.’ People just kind of ignore instead of expanding.”

Opening the door to more than one or a few approved Black playwrights—writers of any color, for that matter—and acknowledging the variety of work being done isn’t just good for the writers themselves but for younger generations as well, as it only increases the opportunity for identification. Aleshea Harris recalls reading Ntozake Shange’s for colored girls who have considered suicide/when the rainbow is enuf when she was an undergrad and having a moment of recognition.

“It was the first time I was experiencing work that sounded like it had come from my body,” Harris says. “To be speaking from a Black woman’s consciousness about things that affect us unapologetically, freely, and honestly, in a way that felt really familiar to me, was life-changing. Because I understood that I could do the same.”

Throughout their early careers, these Black playwrights learned just how crucial it is to be able to read and hear onstage voices that sound like them. Dominique Morisseau, a 2018 MacArthur “genius” grant recipient, points out that without the ability to see a reflection of themselves in the arts, it’s hard for people to understand how they fit into “the human narrative.” Without that, she says, “You don’t feel like you even matter in this world.”

Morisseau credits predecessors like Shange and George C. Wolfe for opening the door for her playwriting. It was their work, she said, that emboldened her to write a choreopoem as her first play. Taking further inspiration from a fellow Detroiter, Pearl Cleage, and from the way Wilson captured Pittsburgh in his 10-play Century Cycle, Morisseau conceived the Detroit Project, a trilogy of plays examining the social, economic, racial, and political history of her hometown. The trilogy includes Paradise Blue, Detroit ’67, and Skeleton Crew.

Morisseau notes that, though she writes about a culture and people that are personal to her, it’s also her job as an artist to agitate and ask difficult questions. She writes with respect and love for her community, but not in complete deference to it. Skeleton Crew, for instance, puts its Detroit auto-worker characters through the moral wringer as they fight for survival during the Great Recession.

Like others in this new wave of Black writers, Morisseau is quick to note her debt to previous generations. While today’s writers are being rightfully touted for their fearless work, they didn’t invent badassery, and credit is due.

“There’s no way I could be unapologetically Black without them,” Morisseau said. “There’s no way that I could do what I’m doing if they didn’t take some hits before me.”

Playwright Marcus Gardley echoes Morisseau, agreeing that the work of the Black playwrights who came before them didn’t and still doesn’t get enough acclaim. His predecessors changed the idea of what “universal” could mean, he says, with stories that showed Black people were people like everyone else.

“That work is described as ‘angry’ and all of these terms, which I find laughable,” says Gardley. “It’s Black work that is unabashedly Black. Black work that is competent. Black work that is not only for Black people but seen through a Black lens. I think that was huge.”

Aleshea Harris looks back even further, to the way Black performers once tried to break out of minstrelsy in favor of telling stories more true to Black people’s lived experiences. White audiences rejected this impulse, as there’s always been an expectation, based in whiteness and white supremacy, that Black artists, when allowed to write or perform, must present a certain way. She has taken succor from those who’ve defied these expectations; as she puts it, “Inspiration comes when someone opens a door that I didn’t even know existed and gives me permission to do something.” In addition to Shange, she cited Adrienne Kennedy’s Funnyhouse of a Negro and the plays of Suzan-Lori Parks as door openers for her.

Even artists who pushed the envelope in their time can have their radicalism sanitized. Recalling August Wilson’s historic 1996 speech, “The Ground on Which I Stand,” at a TCG conference, Harris noted that though Wilson and his work were fired in the kiln of the Black Power and Black Arts movements of the 1960s, his work has since been repackaged to become palatable to white audiences, in much the way the radicalism of figures like Martin Luther King Jr. has been sanded away.

Harris worries that the same thing may happen to today’s boundary-breaking work. “White theatre, white culture will receive it and it will become safe because it’s become the cool thing to go and see and do,” she says. “The conversations around how and why it was radical and how and why it was unrepentantly Black—when that’s forgotten, it will seem safe.”

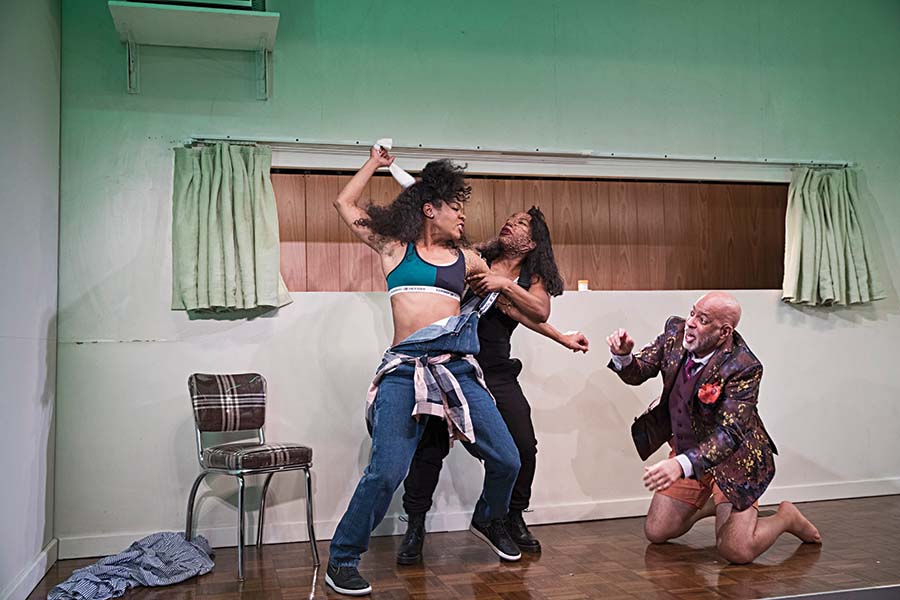

Even now there seems to be a box within which the predominantly white theatre world places Black playwrights. Harris saw it with her play Is God Is, a violent modern myth about twin sisters crossing the country to exact revenge. It is not autobiographical, nor is it about race relations with white people. But in many of the reactions to her play, Harris says people tried to make her play about those things. There’s a mindset, she says, that Black narratives must be “about how hard it is to be Black and how we overcome.” There’s a certain comfort to that narrative—for white audiences, especially. “Some people aren’t even aware that they’re carrying that expectation and bias,” Harris says. “I feel like folks are always going to expect certain things of us. But I don’t let that stop me from doing what I want to do.”

For her part, Ngozi Anyanwu felt the need to write about the Black experience from a different angle. As a Nigerian American, she saw a gap in how Africans were being portrayed.

“Every time an African would be referred to,” Anyanwu says, “we talked about the apartheid, we talked about the war in Rwanda, we talked about the girls in Congo. I was very cognizant of the fact that every time an African experience was being represented in theatre, it was under intense trauma and duress.”

Like other Black playwrights—including fellow African-immigrant-descended playwrights Danai Gurira and Mfoniso Udofia—Anyanwu felt the pinch of these expectations. Good Grief, which played last year at Off-Broadway’s Vineyard Theatre with the playwright in the lead role, is a coming-of-age story about a young suburban woman in Pennsylvania who happens to have Nigerian American immigrant parents.

While white audiences may have expected a traumatic narrative, Nigerian Americans had their own preconceptions about the play as well. Some of these audiences were excited to have a relatable, everyday American story told about their experience, but Anyanwu found that the narrative around her play shifted once conversations about it began. Suddenly it wasn’t about her play anymore but about her, as a Nigerian American, addressing her experience.

“That’s not what my play is about, actually,” Anyanwu says. “I think that’s interesting. People tend to not focus on the story of the play. They want the story of the playwrights.”

This has led to a sort of crossroads for Anyanwu as she works on future plays. She asks herself, echoing a refrain of many writers of color whose work is produced by and for predominantly white theatres and audiences, “Am I telling my story or am I pimping my culture?” She’s also faced with thoughts about the current politics in the U.S. If her play doesn’t have something to say about police killings of unarmed Black men, is the work still relevant? Does it still matter?

Of course it does. “Because you should just tell the truth of just being,” she says. “These are stories that are just as prevalent and mundane and dramatic as anyone else’s story.”

Gardley agrees. While he finds it important to tell stories he sees aren’t otherwise being told—in his case, about the lives of Black women in particular—he doesn’t see his mandate as speaking for the race, or only about race. “Race is part of the conversation,” Gardley says, “but they’re talking about something way more complicated than just race. I think it’s important that we, as Black writers, are looked at as artists who can do anything.”

Gardley cites his play A Wonder in My Soul as an example. It centers around a hair salon whose owners, in the face of gentrification and neighborhood crime, must decide whether to relocate their salon or stay and support their neighborhood. While the characters in the play are Black, the themes of struggling with gentrification and of women owning their own business aren’t exclusive to the Black community. But Gardley found that reviews of the play—last year at Chicago’s Victory Gardens and at Baltimore Center Stage—mostly compared his work to that of other playwrights with the same skin color rather than all playwrights with similar subject matter. He finds this myopia dispiriting.

“What they don’t realize they’re doing is they’re saying we’re only speaking about Black things,” says Gardley. “I know most Black playwrights working in this country, and it drives us all crazy. We want to be compared to more than just Black writers. We want to be part of the national conversation.”

Holter agrees, noting the freedom that white writers have to tackle any subject or character, including people of color. Holter says that when he’s had blind commissions, ostensibly to write about whatever he wanted, theatres seemed puzzled when he turned in plays that weren’t about race or “struggle.”

“When a white writer writes outside of their race,” says Holter, “people are interested in that because it seems brave for that white writer to do that. But I think when a writer of color writes outside their race, people are confused, a little bit angry.”

This is just one of many double standards Holter sees. Not only are white playwrights often encouraged to write outside their race, they are typically expected to work with diverse teams. But Holter has had the experience where his play is filling the Black “slot”—the one show in a season with a Black playwright, Black director, Black actors, etc. If Holter deigns to request a white director, it can cause friction, because theatres have an unwritten quota that needs to be filled by the one Black director. Moving past this conversation, Holter says, raises the larger question of what kinds of Black stories theatres put onstage.

“I’m just trying to get to that point where we can live outside of whiteness,” Holter says. “We do every single day. So many theatres will only put us onstage when it’s about our overcoming suffering at the hands of white people, or our having suffering inflicted on us by white people.”

It’s not a hard and fast rule that predominantly white theatres handle these situations poorly, or that theatres of color invariably handle them well. But Harris says she has found it easier to have conversations with POC-run theatres because they understand the particular challenges she faces.

For Morisseau, these conversations often center on who is assigned to be her dramaturg. Many times, she explains, playwrights are allocated a theatre’s staff dramaturg or literary manager, who may not fully understand the playwright’s voice or lacks cultural grounding in the play’s subject.

“If you were able to bring your own dramaturg,” Morisseau advises, “and find someone who’s going to help mine your voice with you, we might be seeing much more layered work from all writers everywhere. But I don’t think that we get the full cultural development that we are in need of inside of these institutions.”

Anyanwu feels similarly about directors. To bring qualified names to the table, she says, it’s invaluable for playwrights to see as much work as they can—become “nerds of the theatre,” as she puts it—so they can help choose directors for their plays. At New York City’s Atlantic Theater Company, for instance, she suggested Awoye Timpo as the director of The Homecoming Queen. Artistic director Neil Pepe didn’t know Timpo, so Anyanwu suggested they have lunch, and the rest is history.

It’s not all about race, Anyanwu insists, but about crafting the right team. She looks for a shared understanding. “You get to be in a room with a bunch of people,” Anyanwu says. “And you want to be in a room with a bunch of people who look like the people from your play, and people who know what they’re talking about.”

While some of these conversations may be easier to have at Black-run theatres, many Black playwrights find themselves looking to predominantly white theatres to build their careers. Morisseau, who is on the board of the Detroit Public Theatre, points to a scarcity of grants and funding at smaller organizations.

“They don’t have developmental production grants at the same level that the white institutions have,” Morisseau says. “They don’t have as much space or resources to be able to run full-on development programs that are equivalent to the Public Theater’s Emerging Writers Group, for instance.”

Some of these play development labs, she explains, are largely underwritten by funders. When she was coming up as an artist, she didn’t see the same kinds of largesse available in Black theatres (with the exception of Penumbra Theatre in St. Paul, Minn., she adds). Now that her work has become more visible—in addition to her original plays, she wrote the book for the Broadway musical Ain’t Too Proud: The Life and Times of the Temptations—Morisseau says she makes a concerted effort to work with Black theatre institutions to ensure that her work stays in their spaces as much as in non-Black or predominantly white theatre spaces.

And while she welcomes productions at predominantly white theatres, Morisseau cautions them against turning plays by writers of color into museum pieces or curiosities. Conversations around these productions need to include the audience it was intended for.

“Without having equity in the house and the audience,” Morisseau says, “you are making it a zoo. That’s not fair. I call it #NoMoreJimCrowTheatre, because it feels very Jim Crow to me to have people of color onstage and see no people of color in the audience.”

Holter has a quick solution: Simply start programming seasons entirely written and directed by people of color. Theatres can decide that now is the time to try this for a few years and see if it changes their audiences. The alternative is the same old menu: four plays by white writers and a so-called “special play.” (“The audience can tell it’s special,” Holter says. “They can tell they’re supposed to really, really enjoy this. They can tell that it’s ‘important.’”)

As a positive example, Holter pointed to Chicago’s Victory Gardens, which has produced plays exclusively by women and people of color for the last two seasons. Getting to the point where seasons like these were possible was a process, Victory Gardens artistic director Chay Yew says. This process—which he describes as an effort to find plays that represent voices that weren’t being heard—saw half of the theatre’s subscriber base leave in his first season. But those who enjoyed the new and diverse work stayed, and Victory Gardens has since built a new and more diverse (and younger) audience.

It takes a conscious effort to bring more voices to the table. Creating spaces that cater to people of color, female writers, writers with disabilities, and writers from different social classes, as Gardley points out, can allow future generations of underrepresented playwrights to flourish.

All of these playwrights know that the American theatre hasn’t attained racial justice, any more than the U.S. is as a whole, but they do see signs of progress. Looking ahead to coming generations of Black writers, Morisseau hopes to bequeath them “a sense of freedom. A sense of legacy.” In other words, a history and a future—both an honored lineage and an unlimited horizon. These precious things aren’t just within reach; they are in these writers’ hands.

Jerald Raymond Pierce, a former intern of this magazine, is a writer based in Chicago.