The Bible is a book that’s almost impossible to read cover to cover. It appears, even by the most conservative estimates, to have been written (if you count translators and re-translators) by dozens if not hundreds of hands over several millennia. It is revered by its billions of admirers as a source not merely of gnomic and difficult stories and proverbs but of incontrovertible moral authority.

These qualities—leaving aside politics, tradition, theology, narrative dissonance, money, space and time—make it profoundly difficult to approach dramatically with any kind of objectivity.

None of that has deterred Lisa Peterson and Denis O’Hare, the pair behind the popular and widely acclaimed An Iliad (a more direct adaptation of another notoriously tricky work), from developing and, God willing, staging a play about the ineffable weirdness and allure of the West’s founding text. Their play is called The Good Book, and it begins performances at the Court Theater of Chicago on March 19.

It’s a labor of love. Also some hate. Also a lot of ambivalence.

Neither O’Hare nor Peterson self-applies the term “Christian” or “believer.” Peterson’s perspective is a little recursive: She loves the notion of belief and seems to be edging toward it, though she’s adamant that she doesn’t unreservedly believe. “I wouldn’t have said this until I started working on The Good Book, probably, but I think it’s what happens as you grow into middle age and your parents are growing older,” she sighs. “It’s a time when we all wish for a meaningful structure to our lives. It’s about mortality, really.”

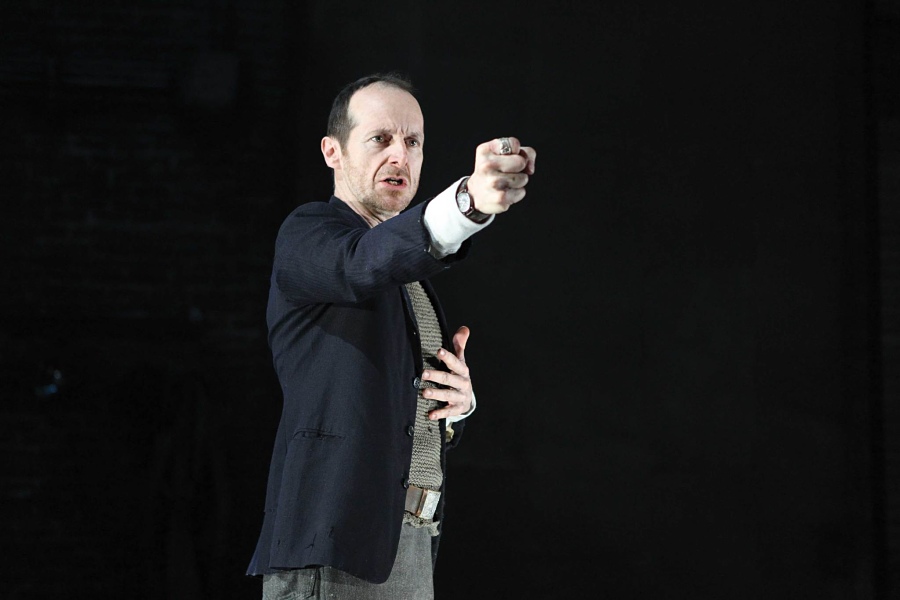

O’Hare passionately loved the Bible and the trappings of Catholicism as a child, and though he immediately, smilingly replies “I’m an atheist” when asked to declare his loyalties, he still maintains a deep affection for the text itself, to say nothing of an exhaustive knowledge of its contents. “We ignore the Bible at our peril,” O’Hare believes. “If we do, we don’t get literary allusions or a great trove of metaphorical possibility, or fully understand 100 percent of medieval art. Samuel Beckett alludes to the Bible. So much of Western culture makes reference to these stories and metaphors.”

And, because those stories and metaphors are complicated and varied, rather than try to reduce the entire Bible to a single evening of theatre, O’Hare and Peterson decided to stage the history of the Bible. Their main conduits are two experts—one a devout young man, the other a world-weary, atheistic college professor—who comment on the Bible and its creation while wrestling with their own faith or lack thereof.

The first of these main characters in The Good Book is the boy, Connor, whose childhood has something to do with O’Hare’s own (though the writer/actor dances around the question of how much of Connor is him and how much is invented). Connor’s sexual awakening—he’s gay and anxious not to think about it, for fear of coming into conflict with his cherished Catholic faith—is a major plot thread. O’Hare and Peterson detail his story from the perspective of a man within whom Catholic doctrine, hormones and Scripture itself were once locked in conflict.

That conflict is still going on, albeit more gently these days. O’Hare says he takes his three-and-a-half-year-old son to church and reads to him from a book of Bible stories. “My husband’s not into it,” O’Hare admits. “He’ll ask me why and I’ll say, ‘Because he’s got to know!’”

When the play was first commissioned by the Court, O’Hare and Peterson envisioned taking as honestly combative a stance as they could toward the Bible—“to invalidate it,” as O’Hare puts it—and toward people who believe in it. “I had become increasingly angry at the way the Bible was used against me as a gay person,” O’Hare says, “and that people in this country were politically justifying actions and laws with this book.”

O’Hare has obviously consumed a great deal of conservative literature on the topics of the Bible and politics, so that his every thought comes verbally footnoted to preempt any attempt on the part of his interlocutor to volley back a cheap shot. “I made my own pamphlet for a while,” he says, “called ‘The Seven Verses You Think You Know.’” O’Hare borrowed the concept from a gay pastor he’d found online who had intricate, contextually specific rebuttals to the use of various Bible verses to shame contemporary gay men and women. “I would just hand it out on the street!”

Over the past three years, Peterson and O’Hare have set about learning the history of the Bible, so a vast period of time is dramatized in The Good Book, from the legend of the Septuagint (the translation of the Hebrew Bible into Greek, ostensibly by 70 scholars in 70 days); to the verbal swordplay, realized onstage as literal swordplay, between James I and Puritan intellectual John Rainolds over the King James Version; to the sniping over gender-neutral language during the 1980s translation of the New Revised Standard Version.

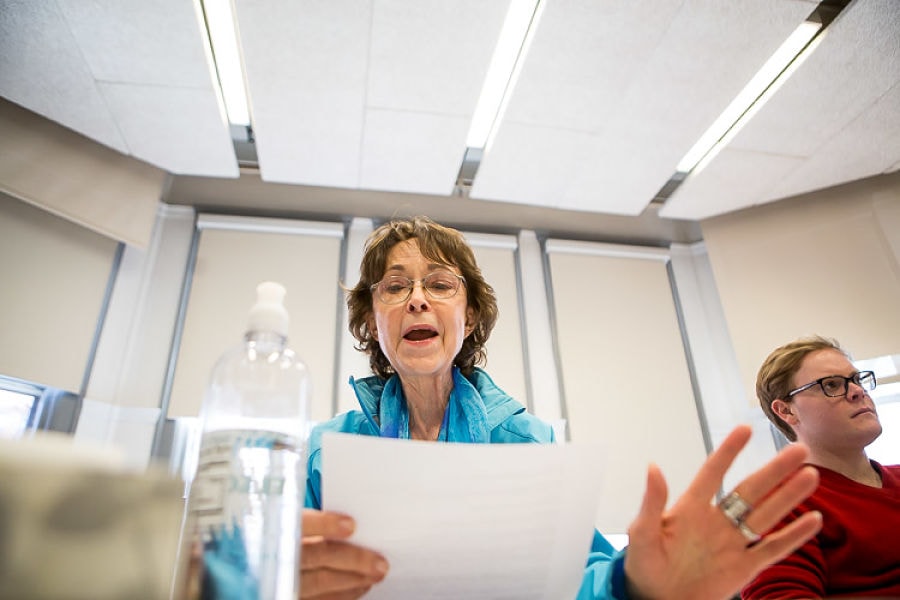

They had help along the way. When they told Court artistic director Charles Newell they were working on a play about the Bible but needed help from biblical scholars, he told them, “Well, I’m at the University of Chicago and there’s a divinity school, and we’ve got biblical scholars.” He helped the pair find Margaret Mitchell (no relation to the famous author), who, along with Peterson and the writers’ mutual friend, actor Blair Brown, formed the basis of the second primary character in the play, Miriam, a college professor who teaches the Bible, though she herself is an atheist.

At the beginning of the process, O’Hare and Peterson set out to engage the audience in much the same way a platoon engages enemy soldiers.

“Part of what we want to do in our play is to ask questions and to reveal some of the fascinating history of the process,” O’Hare says. He characterizes the play’s purpose as “if I’m being uncharitable, to destabilize their faith—or, if I’m being charitable, it’s to allow them to appreciate a little more the Bible’s human construction, and to admire more the consistency of thought and of inspiration and of the devotion people have had to these ideas.”

That was the plan, anyway. Skepticism, despair, anger at God—these, it turns out, aren’t so much arguments with the Bible as arguments in the Bible. “It’s such an amazing compendium,” Peterson says. “It has everything for everybody. It’s a grab bag, and you could find anything you wanted, really, in there.”

Indeed, even the characters in the play object to some of the language in the Bible. “Disgusting!” declares one scholar, on the verge of ripping the book of Ecclesiastes to pieces. Then he reads: “What do people gain from their labors / At which they toil under the sun? / Generations come and generations go, / But the earth remains forever. / What has been will be again, / What has been done will be done again; / There is nothing new under the sun.” He can’t get rid of that language, of course. It’s beautiful.

That’s something O’Hare himself feels intensely—he may hate being swatted at with the Bible by anti-gay groups, but he adores the text itself. “Great literature is great literature,” he says, almost ruefully.

“One of the great fears we’ve had in writing this is that we wouldn’t be radical enough, and I think that fear has come true,” O’Hare admits. “Biblical scholars just nod and smile. We keep asking ourselves, ‘What are we doing wrong? No one is running from the room!’” O’Hare’s probably being too hard on himself—the history of blasphemy is long, storied and rich, and if you have trouble saying something that hasn’t been said by some commentator from the 4th-century Gnostics to “South Park,” it’s nothing to be ashamed of.

“What constitutes a sincerely held belief?” O’Hare wonders rhetorically. “How do we test that? Do we test it? How do we get into interpretation? How do I get to decide the correct meaning of this document?”

That, ultimately, is what The Good Book is about: Who gets to decide. Both Peterson and O’Hare say that the third character in the play is the Bible itself, as portrayed by actors playing the people who excised sections, added the good bits, and saved its greatest treasures from censorship in all its various forms. The legwork will undoubtedly feed the pair’s next project, The Song of Rome, at the McCarter Theatre Center in New Jersey (“We want to try to tell the entire story of the rise and fall of Rome, and we want to learn a lot about Roman theatre, which is a subject we don’t know much about,” says Peterson), but it’s also food for thought offstage.

Both, after all, are keenly aware of the power of the Bible and the power of stagecraft. Peterson recalls with a smile that she had “a total conversion experience at Godspell.” After seeing a community theatre production in Santa Cruz, Calif., the writer/director, then a high-schooler, got baptized and confirmed shortly thereafter, entirely of her own volition. It didn’t take—Peterson ends every rumination on faith with “but I don’t believe”—but the memory of the experience is sweet. “I always joke that I was just confused: I was falling in love with the theatre,” she says.

For O’Hare’s part, he sees himself as still a work in progress. “I think that for me the door is open,” he allows. “Who I am at 52 is not who I was at 22 or who I was at 12.” He pauses. “But oddly, I am the exact same person.”

Sam Thielman is a reporter and critic based in Brooklyn, NY. His Tumblr is hesnotewell.tumblr.com and his Twitter handle is @samthielman.