In the spring of 1971, Joe Papp invited Mel Shapiro to direct Two Gentlemen of Verona in the Delacorte and for the mobile unit that would tour the five boroughs. Galt MacDermot would be the composer in residence.

What worried Mel was that the times promised yet another summer of racial unrest. The previous year, actors touring in the mobile unit in the Scottish play had bottles thrown at them. How would the street audience react to this rambling five-act play, with its Renaissance sentiments on courtly love?

Mel asked my help in telescoping 2Gs into a 90-minute structure. Galt, whom we had not met, was on board. What if we used a few songs as subtitles? I wrote lyrics for three or four.

Could we meet with Galt? No. He rarely left his home, a schoolhouse on Staten Island, where he lived with his wife and family. Galt sent word to leave any lyrics on his answering machine.

(I loved learning the detail in Galt’s New York Times obituary that Rado and Ragni had also sent him their lyrics for Hair before meeting him.)

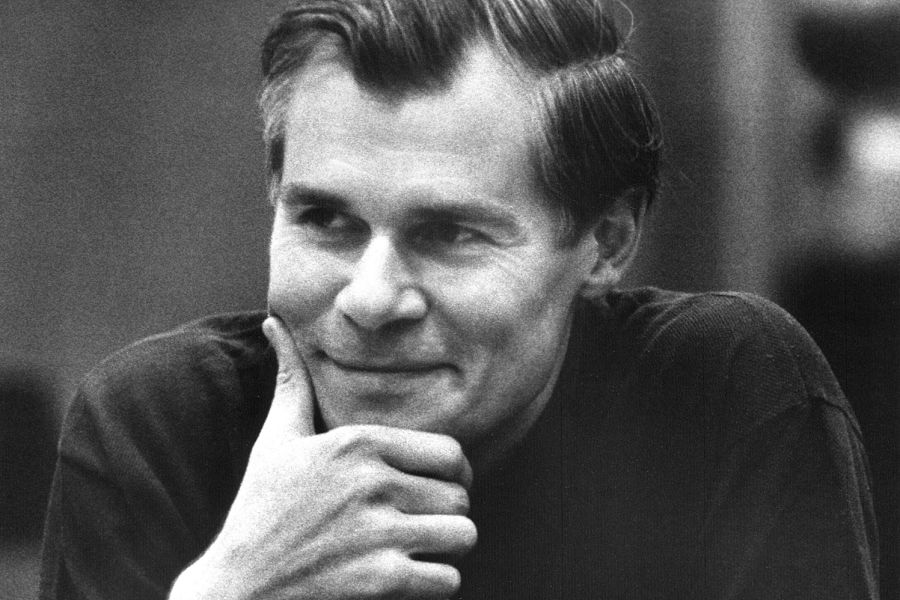

Rehearsals began for a virtually unwritten play. We had 4 weeks to make a show. I don’t know what I expected but when we finally met, Galt bore no resemblance to my idea of who the composer of Hair might be. I wasn’t prepared for that ironic smile, that detached manner, the serenity that let you know nothing could ruffle this mild Canadian. He didn’t speak much. His hair? 1950s short. His casual clothes? Sears, Roebuck catalogue.

But then he sat at the piano. His true self emerged. Galt’s serene manner became a vacuum to be filled. The songs written in rehearsals poured out. His rhythm man, Bernie Purdie, his African-American alter ego, would appear with his drums. How those rehearsals caught fire. Raul Julia, Carla Pinza, Jonelle Allen, and Clifton Davis led a cast of clowns who knew how to deliver musically and still honor Shakespeare.

The 4 or 5 songs blossomed into more than 30 “tunes,” as Galt called them. I loved writing with Galt. He was a dramatist who knew how to write not just a grab bag of songs but intuitively build them into a score. He also knew where the jokes were.

As Mel Shapiro said the other day, Galt loved words: “Words put together as rhymes, free verse, monologues, dialogue; words that made sense or nonsense, and mainly words that were witty and made him laugh.”

The afternoon Galt, Jonelle, Clifton, and I built Night Letter, which would become 2Gs‘ showstopper, is still one of the most exhilarating, time-stopping events in my long life. We were all so busy working, we never stopped for a meal, a drink. There was so much joy between us. I couldn’t wait for the show to open and become friends with this man.

We opened at the Delacorte. Galt’s music, the performers, Shakespeare blended together into an irresistible force. The effect of the mobile unit was one of joy in the streets.

After the show opened and transferred—that magical word—I saw Galt at business meetings and rehearsals and subsequent openings but never for that meal. He had to get back to Staten Island.

The show played a year and a half; two companies toured; there was a London production. Irving Wardle in the London Times called 2Gs “an ode to joy.” Through it all Galt remained a serene, gnomic mystery box.

I learned more about him in his New York Times obituary than I ever knew. And then American Theatre magazine asked me to write about Galt. Here’s what I can say: People were distractions from the music. All of life was an interruption until he sat at a keyboard and his real demonic musical life began.

In 1987, after not seeing him for years, I sent him a lyric for a play I had written. A few days later the music appeared in the mail.

Mel had a similar experience in the last decade. “When my grandson was born I wrote a lyric and asked Galt if he would set it,” Mel recalled. “He made me rework it five times until he put it to wonderful music which we treasure. He meant much to me and my wife and will always miss him.”

Was Galt Catholic? I have this image of him at his final moments in Staten Island, with the priest standing over him—and Galt setting the words of the last rites to music.