Although Alvin Epstein was 93 when his life came to an end, his passing still seemed sadly premature. A true man of the theatre, he was equally inspiring as actor, director, teacher, and mime, though the latter function was something he was curiously reluctant to pass on to others.

I first experienced Alvin’s genius when he returned to this country from his sojourn in France to appear on Broadway with Marcel Marceau. That appearance was voiceless, but was soon followed by his performance as the verbally diarrhetic Lucky in Waiting for Godot.

Clearly, this was the kind of artist needed for the theatre we had founded in New Haven, Conn., in 1966, following Yale President Kingman Brewster’s invitation for me to become dean of the Yale Drama School. A shameless exploiter, I soon managed to entice Alvin into teaching our acting students, whom he transformed with his modest art and generous time. And, of course, as associate director of Yale Rep, he was responsible for some of our most celebrated and transforming productions.

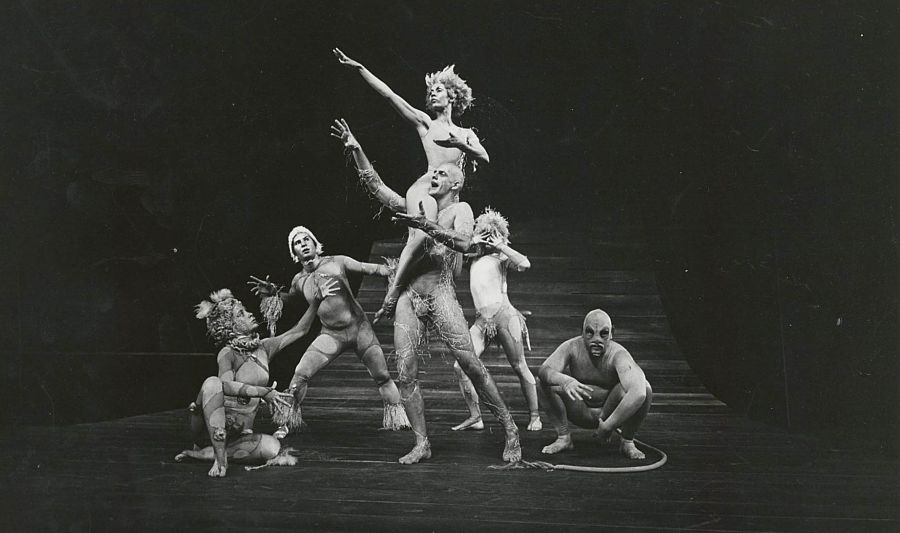

Interestingly enough, considering the simplicity of his earlier work, Alvin capped this off with his exquisite production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, with its unforgettable image of Carmen de Lavallade and Christopher Lloyd, as Titania and Oberon, sliding down a wooden scoop to the accompaniment of an indelible score. Alvin had conceived the brilliant idea of mixing the language of Shakespeare with the music of Henry Purcell, but more than that he made the decision visible by putting orchestra and chorus onstage. In New Haven these facilities were provided by the Music School under the direction of Otto Werner-Mueller. In Cambridge, Mass., where the production opened as the inaugural (and almost immediately) signature piece of the newly formed American Repertory Theatre, it was accompanied by the Banchetto Musicale using Werner-Mueller’s adaptation under the direction of Daniel Stepner.

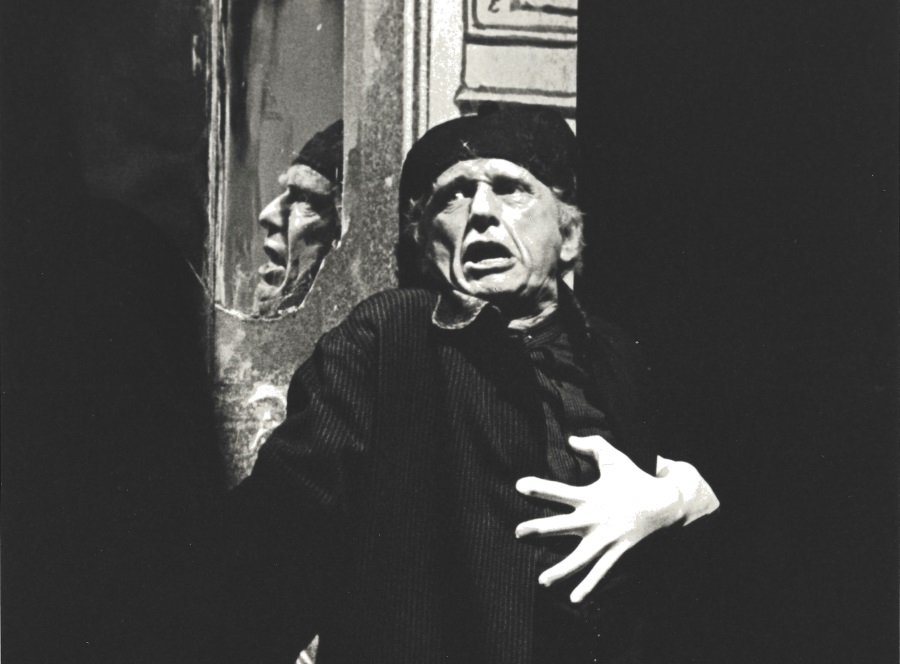

Alvin’s histrionic versatility was such that he could play both the Fool in Lear and Lear in Lear, remaining equally effective making long speeches or remaining mute. That is why Samuel Beckett was such a perfect fit for him. It is also why his command of Shakespeare almost amounted to genius.

Certainly Alvin’s Midsummer will live in memory as long as memory lives. Theatre life in New Haven had always been a struggle, unlike Cambridge, where we were a triumph the moment the ART company walked upon the Loeb stage. That was primarily because of Alvin’s Midsummer. “The theatre Boston has been waiting for,” exclaimed Kevin Kelly in his first review of our work in The Boston Globe. And though our productions never again quite captured the same delirious level of praise, Kelly’s reviews were usually to remain positive and supportive.

The Harvard faculty was more difficult to please, but by this time I knew how to neutralize the inevitable academic resistance: Appropriate it. With Alvin’s participation, I began to hold public seminars with Harvard faculty in which they were encouraged to air their opinions about our plays and productions. With this Machiavellian strategem, resistance soon faded away.

Between Yale Rep and the ART, Alvin played more than 50 roles, while directing at least 10 productions. His Midsummer toured Europe and China and was quickly considered a masterpiece. But brilliant as that achievement was, it could not have been accomplished without Alvin’s special spirit and personality. Some directors—Fellini, for example—achieve their effects through fear and thunder. Alvin threw bouquets. To win Alvin’s favor actors were willing to put up with the most difficult procedures, not only because of the satisfying results, but because they might win a hint of a smile or a burst of applause from their director or teacher.

His Midsummer proved a testing ground for almost every actor who came through Yale Drama School, Yale Rep, the ART Institute, and the ART. Virtually every student or company member sharpened their teeth on it. Among the actors who played the lovers were Meryl Streep, Cherry Jones, Sigourney Weaver, Steve Rowe, and Rick Elice. The rustics included Jeremy Geidt, Max Wright, Joe Grifasi, Johnny Bottoms, and Remo Airaldi. Fairies included the aforementioned Lloyd and de Lavallade, Mark Linn-Baker, and Tommy Derrah, while Liz Norment, Harry Murphy, Karen Macdonald, and Lloyd were among the court figures. Most of our kids (including my young son Danny) had the opportunity to play one of the fairy children. I even tried a welcoming speech myself before being hooted off the stage.

But the principal player was always Alvin Epstein in his various functions, until, in his first encounter with the disease that killed him, he was forced to miss a season and, joining his sister Sandra in their Connecticut home, take to his bed to battle for his survival. That battle now has ended, and Alvin Epstein, never capable of a cliché, has literally played his last role. Not least in our memories, however, where he continues his incomparable career and where his splendid achievements will live forever.