In the 1990s, David Zinn carved out a good career as a costume designer. But with the new millennium dawning, he wondered if it was too good. “I was concerned about getting pegged as just a costume designer,” says Zinn, a burly, bearded fellow who had studied both costume and set design at New York University. He fretted, “Maybe I was not meant to be a set designer.”

What he calls “the big blow” came in 2000 from a devastating rejection by George Street Playhouse in New Brunswick, N.J. The company had entrusted him with the set for director Ted Sod’s production of In Between, “a touring kids’ show for the education department, made for about four dollars,” Zinn recalls. When Sod tried hiring him to design the set of Margaret Edson’s Wit, however, George Street said he could not use Zinn—whose set-design experience at that point had been for shoestring-budget companies like Target Margin Theater or small regional houses—on such a big project.

It was their loss, of course. Zinn, 46, has since become a 2008 Obie winner for sustained excellence in both scenic and costume design. In fact, his accolades for set design since 2008—which include a Drama Desk nomination, four Lucille Lortel nominations and five Henry Hewes nominations (and one win)—may actually outshine his acclaim for costume design. On that side of the ledger, he’s earned a Tony nomination, plus two Hewes and one Lortel nomination.

How did he swing the dual identity? To fulfill his designer dreams, Zinn had to veer slightly off track, into the world of opera. Shortly after the Wit nightmare, Chas Rader-Sheiber invited Zinn out West to the Santa Fe Opera to design the set and costumes for La clemenza di Tito.

“After the dispiriting George Street experience, I figured there was no way they’d let me do the set for a production that big,” Zinn says with a shrug. “But, sight unseen, they said, ‘Sure.’”

Zinn proceeded to work on several operas with Rader-Sheiber, and suddenly, he says, “I had these big set designs I could show people and they would say, ‘Oh, you do those things.’ I’d never assisted on a Broadway set, but New York people saw these designs and realized I understand big spaces and I understand the vocabulary.”

Zinn calls the Santa Fe Opera experience “one of those weird miracles,” but the fact is he had a lifetime of preparation for it, dating back to when he was a seven-year-old actor in a local production of Annie on Bainbridge Island near Seattle.

Young Zinn was instantly struck by the set. “Miss Hannigan’s office had a door with a window in it so you could see the light in the hallway—which demonstrated the idea that there’s this other thing you can suggest that isn’t there,” recalls Zinn, who went home and built his own Annie set out of cardboard. “The bug was deep in me at that point.”

Zinn, whose cozy Park Slope apartment is currently crowded with working set models for the Broadway production of Fun Home and the Off-Broadway production of Placebo, found backstage internships in Seattle during high school, painting scenery and learning about theatre. “I knew this was the kind of work I wanted to do,” he says.

Zinn’s father had “always carried a torch for the theatre”—he’d done modeling and acting in New York before settling down and working for Lockheed—and his parents were so supportive that when he told his mother he was considering the University of Washington instead of New York University’s design program, she thought he was getting cold feet and declared, “Over my dead body.” (Actually, Zinn was in love with an older man on the West Coast, which he didn’t admit to his mom at the time.) His mother got her way, and “that’s when I realized that they recognized my passion for this work,” he says.

NYU provided formal training, but his inspiration came from the city itself. “My two big loves were musicals and avant-garde theatre,” Zinn allows, so he was constantly exploring, taking in shows by the Wooster Group, Richard Foreman and others. “Everything in New York was mind-boggling.”

He did not, however, find the mentor he’d hoped to discover at the school. The professors that others considered influential he saw as figures to rebel against. “I thought I wanted to be taken under somebody’s wing,” he says. “I was probably a really bratty, stubborn kid.” Parts of the school experience were disappointing and frustrating, but Zinn sees now that “a lot of good came from it stylistically.”

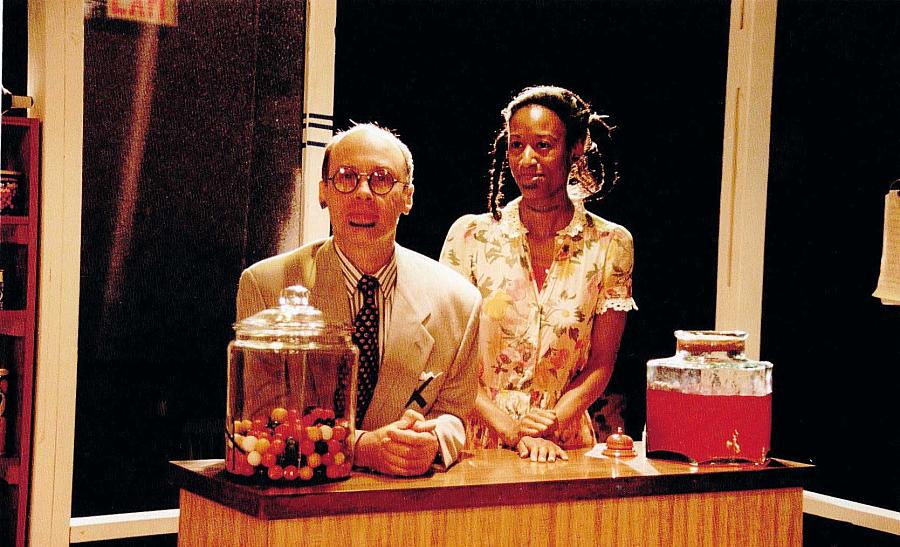

And maybe he wanted more of a partner anyway, which he found shortly after graduation when he began designing for David Herskovits at the director’s fledgling Target Margin Theater.

“I was raring with ideas, and David challenged me in a lot of ways,” Zinn testifies. “Working with him was the most exciting thing for me.”

“He was so open,” Herskovits says of his early collaborator, “and he was a pitch-in guy.” Zinn was able to indulge his outlandish ideas and “embrace our wonderful loop of collaboration,” Herskovits says. “He could turn things to his own sensibility, take that crazy stuff and twist it and give it back.”

Zinn still toyed with the idea of returning to Seattle and routinely took jobs there. In 1995, he sublet his New York apartment for six months and lined up shows out West. (In part, he confesses, this was “another man-based decision, though I tried telling myself it wasn’t.”) But as soon as he landed in Seattle, he thought, “I’m out of my mind. I’ve been looking for a home, but I do have a home with a lot of friends, and it’s in New York.”

Beyond the theatre, Zinn had also found a community in New York through ACT UP, the political organization, in which he was active for years. “It was the cause of a lifetime,” he says. “AIDS is how I understood sexuality and politics. ACT UP was an enormous part of my life.”

While Zinn is no longer on the front lines of causes like AIDS or arts funding—“It’s not my gift,” he says, “because I get so angry and I’m not a great articulator”—he does retain the “fury of a political activist.” (“If you want to send a guy to beat up Republicans, to punch them in the face and run down the hall, I would be amazing. Otherwise I’ll write a check.”)

Meanwhile, Zinn’s costume work kept evolving. He moved away from influences like Bob Crowley and Richard Hudson. “I played through my interest in theatricalized shapes and style. I wanted my work to be less costumey and more like clothes.”

He broke through to Broadway in 2007, doing costumes for Xanadu and A Tale of Two Cities. His parents were not well enough to travel to New York but “were very excited. It’s crazy to share that, since on some level it was the dream of my dad. I feel really lucky.”

In 2010, Zinn garnered his first Tony nomination, for Sarah Ruhl’s In the Next Room (or the vibrator play). “It was overwhelming, really amazing,” he says. “And then it’s the next day.”

For Zinn, getting back to the grindstone these days means far bigger budgets and ongoing relationships with top directors like Robert Woodruff, Joe Mantello and Sam Gold.

Gold’s first encounter with Zinn’s work was on Charles Mee’s Paradise Park. The director was taken with “how he squeezed out so many moods and emotions in a real space.” Gold adds that he and Zinn trust each other and can push each other to try new ideas.

“I can’t stress enough how much I feel like I got hit by the lucky stick,” Zinn says of the partnership, though he did learn that you can have too much of a good thing in 2013 when he was simultaneously designing costumes for Mantello’s staging of The Other Place and Gold’s Picnic revival.

“I thought I could do both without telling them,” Zinn recalls, but the overlapping tech rehearsals stretched him too thin. “It was the worst idea I ever had. They were both really mad at me.”

When a similar situation arose this year with The Last Ship (Zinn did costumes and set for Mantello) and The Real Thing (he did the set for Gold), he was upfront with both men. “It was still crazy, but what an amazing problem to have!”

Zinn has learned to stick to his aesthetic, yet satisfy each director with whom he works. “I love walls, big gorilla-sized walls that don’t move, but Joe likes the ability for the wall to go away,” he explains. For Last Ship, “I was charged with making the space feel permanent, yet it also had to be able to go away, or transparent-ize…is that a word? It is now.”

The Real Thing posed its own challenges. Tony Walton’s original Broadway design on a turntable was highly praised (and Tony-nominated), but Gold and Zinn took a different approach, setting everything in one space. The all-white set, with its high walls of out-of-reach books, effectively conveyed several ideas: that Stoppard’s character Henry wanted to stand out, that he might seem charming and intellectual on the surface, but that he was ultimately cold and remote.

Even as he moved up to Broadway budgets, Zinn says he draws on the creativity of his do-it-yourself days at Target Margin. He also remains devoted to his own notions of beauty and elegance. Herskovits says they found common ground in trying to beautify the awkward and obtuse. “If something is too beautiful, it might be ravishing but also soul-destroying,” the director reasons.

Zinn says his years with Herskovits left him aiming to find the poignant beauty even in “the big guy on the bus who doesn’t really fit into the seat. I love that guy.”

He used to proudly describe his sets as “clunky,” but now, he says with a laugh, he is opting for “muscular, since I’m wrestling with the space.” His set for The Last Ship is classic Zinn: He describes it as “massive but with a sort of elegance to it, with a non-theatrical realism. I like to resist the obvious elegance and find it in a harder way. How ugly can you make something and still keep it beautiful?”

Arts reporter Stuart Miller writes regularly for this magazine.