Theatre has come a long way from the days when “lighting” meant the ability to manipulate or work around the movement of the sun. Now theatres have extensive grids that allow designers to hang and focus tens and hundreds of lights to conjure everything from bright sunlight to a candlelit dinner, and all points in between.

Until fairly recently, if you walked into any given theatre that was setting up for tech, you’d often see a lighting designer up on a ladder on the stage, possibly with an assistant down below. They’d hang one, two, maybe a third instrument and focus all of them on the same area. One area, three lights, each with its own gel—specific colors selected to provide a warm or cool or specialized light, as the case may be.

Now you might see something a little different, as theatre is in the midst of a fundamental lighting change—one that will narrow those three instruments down to one, and make them at least partly remotely adjustable. The change has a bulky official name, Light Emitting Diode, but everyone knows it as LED.

“They’re great time-savers,” said lighting designer Kathy A. Perkins of the lighting technology that is sweeping the field. “Where I used to double-hang and triple-hang down and back light, I only do it with one light source. I’m hanging fewer lights, I’m having to focus fewer lights, and it gives me more time in tech.”

This shift will see most if not all of the traditional lighting instruments in theatres replaced with LED lights, which designers previously kept at arm’s length. About a decade ago, around 2007 and 2008, LED lights were just starting to hit stages around the world. In a 2010 interview, Tony Award-winning lighting designer Kevin Adams discussed his use of LEDs in Spring Awakening, Next to Normal, and American Idiot. At the time he used them primarily as a way to light background surfaces, he explained, and as lights to point at the audience. Specifically citing the color that LEDs were able to produce, Adams said that it was “a little bit tricky to get a variety of colors that look handsome on skin.”

That has begun to change. Around the time Adams was using LEDs mainly for supplementary lighting, Electronic Theatre Controls, Inc. (ETC) acquired the Selador product line from Selador co-founders Rob Gerlach and Novella Smith. This game-changing acquisition meant that LEDs, once possessed of a simple red/green/blue combination, could containing seven different colors, thus increasing the nuance available to designers.

Color is the key to LEDs’ appeal, as Michael Lincoln, a lighting designer and professor at Ohio University, explained, and it’s hard to understate how fundamental a change they’re making in the way lighting designers work. “We’ve never had a source before that instantly changes color, that you didn’t have to have some mechanical means of changing the color,” Lincoln marveled.

With incandescent instruments designers must place color gels in front of the light to change the color of the light onstage—the equivalent of draping a scarf over a lamp to set up lighting for a party. And to change the color, the gel either needs to be changed, or another light with a different gel has to be employed. But LEDs change colors digitally, both in the original red/blue/green models and the newer seven-colored instruments.

Lincoln, who has designed more than 300 productions on Broadway, Off-Broadway, and in regional theatre, raved about the “crazy amount of control” that designers have with LEDs. Previously Lincoln had to use what he called “scrollers” if he wanted one incandescent instrument to create different colors during the course of a show. These attachments for the front of lighting instruments allow designers to scroll among multiple different color gels, in a programmed sequence, usually changing over repeatedly throughout a performance.

The trick, and the difficulty, comes in those changeovers. Because scrollers aren’t instantaneous, Lincoln said, a lighting designer needs to carefully figure out when to take a light out so that the machine has time to scroll to the next color—not a terribly quick process sometimes—before the light comes back up. Poor timing, or just a short blackout, can result in the light coming up while odd colors scroll by onstage, like one part of a kaleidoscope that can’t quite keep up with the rest.

LEDs have changed that, effectively putting scrollers out of their misery, according to Lincoln. “We tried to get our (scrollers) fixed and they’re like, ‘Nope, we can’t, sorry, we can’t fix those anymore,’” Lincoln explained. “You can’t get the parts. So as they die, they’re just dead.”

The advantages of LEDs being able to change colors more or less instantaneously means that the conversation designers have around lighting and color is changing, Lincoln said. Those trained in a previous era, he pointed out, are used to discussing color based on Rosco gel labels. For instance, R68 is “sort of a medium blue.” But LED systems, which don’t require gel labels at all, present designers with a circle containing the entire spectrum of light.

“You just click on a place in that color spectrum and say, ‘Give me that color,’” Lincoln said. “You don’t even pay attention to the fact that it’s an old R68 or something like that—it’s just what color looks good onstage right now.”

Designers still go through their extensive planning process before they get into the theatre and start hanging and focusing, but LEDs and their numerous color options give designers more freedom throughout the whole process. Lighting designers always create a color palette that allows them to paint with light during the tech process. What LEDs do is give them the opportunity to expand and adjust that palette on the fly, without needing to climb a ladder to replace a no-longer-needed gel.

Despite the obvious benefits, designers have had their reservations about LEDs.

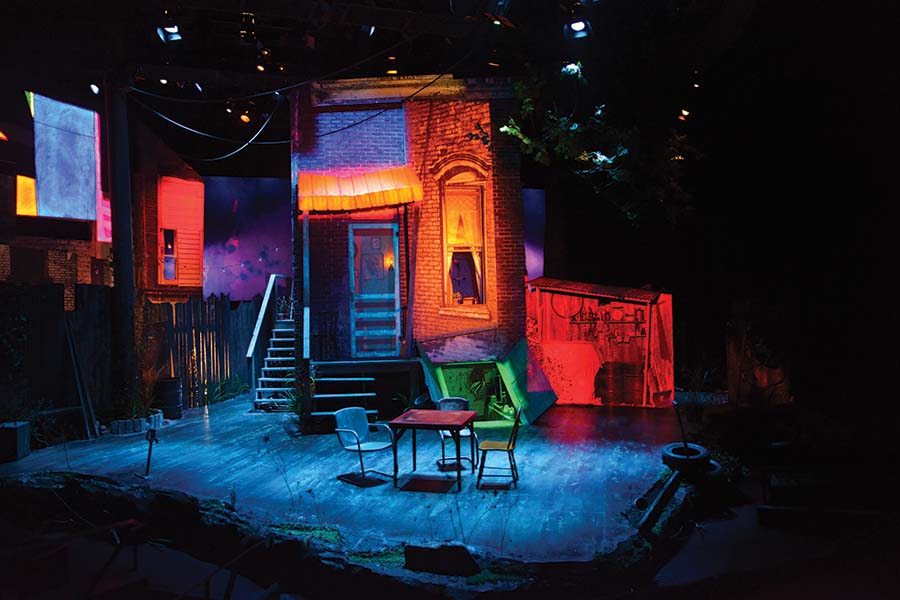

“A lot of us wouldn’t use LEDs because they had such a harsh quality of lighting,” said Perkins, who has worked regionally with theatres such as St. Louis Black Rep, the Goodman, and Steppenwolf. “You could definitely tell it from an incandescent.”

LEDs were first invented in 1962 by Nick Holonyak Jr. while he was working for General Electric. The first LEDs were only red and were used for indicator lights and calculator displays in the 1970s. Soon pale yellow, green, and blue diodes were invented, which quickly led to researchers producing a white light using a combination of red, green, and blue LEDs.

Holonyak wasn’t trying replace incandescent bulbs when he invented LEDs; he wasn’t even trying to create a light source. He was actually trying to make a laser. But as researchers continued to work on his LED discovery, LEDs became brighter and found more uses, thanks to the advantages they presented over incandescent lights. While incandescent bulbs lose 90 percent of their energy as heat, because they use electricity to heat the metal filament inside until it becomes hot, LEDs emit very little heat at all. LEDs also emit light in a specific direction, which reduces the need for elements that can trap light, like reflectors and diffusers, which could result in more than half of the light never leaving the fixture.

Since their invention, LEDs have been used in flashlights, kids’ light-up shoes, optical computer mice, car headlights, and televisions. In addition to being more energy-efficient, LED bulbs can have a lifespan of upwards of 25,000 hours, or more than 25 times longer than incandescent bulbs. Still, despite their advancements, the different science behind LED meant they had their own particular look which theatres weren’t initially eager to accept.

The big change Lincoln has seen over the last two or three years has been in how much more intricate LEDs have become. While LED lights used to emit a distinctive cold blue light, they’re now able to mimic color temperature anywhere from the harsh fluorescent of a hospital room to the warmth of a regular tungsten fixture, like any in-home light bulb.

“The technology, as it always does, advanced rapidly, and now they’re the most sophisticated conventional unit,” Lincoln said. “You can produce a light that I don’t think any lighting designer—if they didn’t know that it was an LED source, they couldn’t tell.”

Lincoln compared the shift to what he saw when the Source Four instrument came out. Conventional instruments before the Source Four used halogen bulbs and produced a warm tungsten light. Lincoln said he heard established designers vow they’d never use the Source Four because it didn’t look like the old units. Now, he points out, the Source Four is dominant in the theatre because it was simply the most sophisticated option.

Despite initial resistance, Lincoln suspects that the LED movement will eventually be widespread. So far, however, the cost of a complete switch-over remains prohibitive for many. As an example of the price difference, Lincoln estimated that, leaving aside bulk deals, a standard Source Four instrument can run a company around $300, while an LED Source Four can be in the neighborhood of $2,300.

Christ Conti, a product manager at Production Resource Group (PRG), sits on the supply end of these transactions. PRG supplies lighting equipment and support for theatre, television, film, concerts, and other major events. Conti sees the additional cost as an unintended consequence of designers so excited to upgrade that they haven’t sufficiently planned for the changeover. One problem is that “the infrastructure,” as Conti explained, “the cable and the power and data distribution infrastructure—to connect the front end, the control console, with the back end of the lights—is a significant increase over conventional tungsten lighting. That adds cost.”

While both LED and tungsten units have power cables, Conti continued, the tungsten power connects to a dimmer, while the LED just connects to a power distribution rack. For the tungsten fixtures, a control cable is simply run to the dimmer, which only needed to control the fixture’s intensity. But for LEDs, a data cable has to be run to each LED fixture. Then, for each LED fixture, there are multiple control channels needed to control the overall intensity, as well as the red LED, the white LED, the blue LED, the green LED, and combinations of the four to make the color the designer chooses. The sheer amount of physical data means that a more refined and capable lighting console is needed.

“Often,” Conti said, “that infrastructure cost gets lost or it gets forgotten about until you have to pay the piper on it.”

But it’s money well spent in the long run, Lincoln noted. LEDs are “really expensive, but then they are so much more efficient; they use about 10 percent of the power that an old fixture uses. Producing organizations have to get on board, or they’re left behind.”

And the increase in availability has started to lead some prices to come down, which should help smaller theatres to afford more. Conti said he’s seen high schools start to buy and use LED tape—thin strips of programmable LEDs that can be attached to set pieces for illumination. LED tape is an easy gateway to LEDs in general, because it’s low-cost and doesn’t require a lot of skill to pull off.

So far the cost of the best LED fixtures has meant that the shift has happened most rapidly where there’s money for it: on Broadway, where producers and rental companies have been willing to invest in the latest technology.

Broadway is also on the front lines of another big change for lighting designers: video projection. In some cases, LED has gotten into that act. On Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark, a show on which PRG worked, LED video screens were used. These large panels can be used behind scenery as a cyc or backdrop, or can even be used as moveable legs, as they were in Spider-Man. Adding these massive video panels—in the case of Spider-Man, eight feet wide and 33 feet high—adds a new challenge for lighting designers, who have to work with the panels and consider them as their own light source.

“It’s an arms race,” Conti said. “When you start incorporating LED video panels, the light levels onstage go up significantly. It’s a big Lite-Brite, for lack of a better term.” He did point out that rarely do they run LED video panels above 30 or 40 percent power, dimming them as much as possible. But even then, “when you have a video wall, it’s hundreds of thousands of LEDs. It puts off a lot of light.”

Both because of cost, and perhaps just ease, many theatres still use traditional projectors for video elements. This has added another element that lighting designers are still figuring out the best way to collaborate with.

“There’s a lot more of a blend now,” Conti said. “We see the lighting guys are wanting to control the light levels onstage a lot better, so they’re working with the video guys or, in many cases, are handling the video themselves. We’re seeing a lot more cross-pollination between the departments, and the lines between the departments are blending.”

Another technological change that’s gaining momentum (literally) is moving lights. Conti pointed out that while moving lights have been fairly common for the last decade or so, the trickle-down of affordable products is in full swing. “It used to be only top-tier productions were able to afford that,” Conti said. “That’s no longer the case. The barrier of entry has been lowered significantly.”

For Perkins, moving lights and products like I-Cue’s have proven invaluable tools. I-Cue attaches a programmable mirror to the front of a basic instrument, effectively turning that instrument into a moving light. Now Perkins is able to handle contemporary plays that call for more offbeat locations and numerous scenes.

“With younger playwrights, they write for TV,” Perkins said. “It’s no longer A Raisin in the Sun, all in the kitchen or the living room. They’re all over the place.”

Moving lights give her the freedom to know that she can give the director as many specials (lights used to highlight a particular area or object) as needed; she never has to say she doesn’t have enough instruments, or that the crew needs to refocus instruments that are already up in the air. She can simply program a moving light to do the heavy lifting she needs.

“Light plots on Broadway—I would say most of them are predominantly moving lights,” Lincoln said. “On Broadway, space is at such a premium because those theatres really aren’t very big. They’re desperate for every square inch, so if you put a bunch of moving lights in, you’ve got ultimate flexibility.”

Between LEDs and moving lights, lighting grids across the country could look completely different within the next few decades—assuming, of course, that the prices for LEDs, moving lights, and the highly coveted moving LEDs come down to something manageable for regional and smaller theatres. The advancements that LEDs have seen have simply made them irresistible to most in the industry.

“If I had enough money,” Lincoln said, “I would go to all LEDs on everything we have.”

Chicago-based writer Jerald Raymond Pierce is a former intern of this magazine.