[This essay was first published Dec. 18, 2003, in the Times Literary Supplement, and is reprinted here with the permission of the author.]

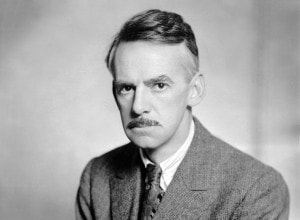

Much that an American playwright needs to know can be learned by studying Eugene Gladstone O’Neill’s life and work. He read a lot. His income went up and down and was never reliable. His reputation went up and down and was also unreliable. He avoided the film industry entirely. Productions of his work caused him to despair, but he kept writing. He gave up heavy drinking early on and was mostly abstemious, disciplined; he exercised. He wrote his plays in longhand. He took his time. He followed the news; he was politically brave. He wrote of the self and also of the world. He wrote for the stage and also for publication. He was theatrical; he was dialectical. He cultivated a public image; a small crowd of remarkable people intersected with the largely antisocial playwright: Emma Goldman, John Reed, Robert Edmond Jones, Paul Robeson, George Jean Nathan, Sean O’Casey, Hart Crane and, unhappily for O’Neill, Charlie Chaplin, who married his daughter. He made friends with a few important critics. He married someone who believed in his work. Winning big prizes did not protect him from savage assault. He argued with God. He hid from the world. He exhorted himself to write better, dig deeper, and he did.

O’Neill’s body of work is not shapely. His struggles wore him to a frazzle—killed him, probably—and marred and marked his writing: it has been said that he spent a lifetime writing failed plays before he got it right. He wrote 49 plays that lay the groundwork for serious American drama, and only one seriously great one, but great enough to be worth the wait. O’Neill knew that Long Day’s Journey into Night (1941) was his best play (even though he tried to have it hidden from public view until 25 years after his death, and stated clearly in his will that it ought never to be performed onstage; his widow’s betrayal of his wishes must be seen by us as an act of beneficence). He must have known that it was great in a way nothing else he’d written was, great in a way little else written for the theatre was.

O’Neill’s body of work is not shapely. His struggles wore him to a frazzle—killed him, probably—and marred and marked his writing: it has been said that he spent a lifetime writing failed plays before he got it right. He wrote 49 plays that lay the groundwork for serious American drama, and only one seriously great one, but great enough to be worth the wait. O’Neill knew that Long Day’s Journey into Night (1941) was his best play (even though he tried to have it hidden from public view until 25 years after his death, and stated clearly in his will that it ought never to be performed onstage; his widow’s betrayal of his wishes must be seen by us as an act of beneficence). He must have known that it was great in a way nothing else he’d written was, great in a way little else written for the theatre was.

But it’s a grave disservice to O’Neill’s accomplishment to view the rest of his work as mere prelude, an extended vamp towards Long Day’s Journey. The first plays are messy, sometimes embarrassing, but the authority and audacity of an important writer are there at the awkward beginning. Deeply influenced by Gerhart Hauptmann and John Synge, and Christ, the writer O’Neill settled at once among the poor, the despised and the outcast. Inheritor of a theatre grown sluggish with nostalgia and pseudo-historical romance, he wrote with obstreperous ugliness and a kind of carnal glee about abortion, prostitution (like Gladstone, for whom he was named, he was much preoccupied with prostitutes), class, murder and suicide. A few others had engaged in this way with the downside of American life; but O’Neill was attempting, almost from the beginning of his career, to move beyond empathy, compassion and outrage to something else, seeking some tremendous meaning which, he discerned, was beckoning vaguely on the other side of emotion and intellect. All such pursuits risk pretentiousness, clunky poetry, dramaturgical and aesthetic disaster, of which O’Neill delivered a generous portion. He was a writer-explorer in the tradition of Herman Melville, foremost of America’s seafaring mythologists, for whom, as with O’Neill, the ocean is a vast incubatory of metaphor. Melville’s prayer, from Mardi, might have been O’Neill’s own:

Fiery yearnings their own phantom future make, and deem it present. So if, after all these fearful, fainting trances, the verdict be, the golden haven was not gained;–yet, in bold quest thereof, better to sink in boundless deeps, than float on vulgar shoals; and give me, ye Gods, an utter wreck, if wreck I do.

As for Melville, time aboard a ship on the open sea was for O’Neill the equivalent of a birth trauma; he revisited it again and again in his plays, as a place for exploring “high interiors.” “High interiors” is O’Neill quoting Melville, in a promised-but-not-delivered introduction to White Buildings (1926), the first collection of poems by Hart Crane, another writer in whose life and art the sea has a fateful significance (O’Neill was an early champion of Crane’s poetry). O’Neill’s maturity as a writer is announced with his one-act sea plays, In the Zone, Ile, The Long Voyage Home—the title of which was used for John Ford’s magnificent film, starring John Wayne, which comprises parts of all the sea plays—and The Moon of the Caribbees.

The tragically landlocked Beyond the Horizon (1920), his first worthwhile full-length play, follows almost immediately, and quickly after that he wrote a good but sentimental comedy, Chris Christofersen [sic], and then rewrote it: “Anna Christie.” Anna seems to have convinced him to make a decisive break with conventional dramaturgy and the lightness exacted as the price for theatrical success; he never attempted it again. With his next play, The Emperor Jones, O’Neill asked his audience to look at race and the legacy of slavery in American history. When he repeated the request, four years later, with All God’s Chillun Got Wings (1924), a play about a mixed-race couple, New York City explored legal means to stop the production, affrighted by the spectacle of a white actress kissing the hand of Paul Robeson. The city authorities settled on the ploy of refusing to allow children to act in the production; but the scenes in which the children appear were read aloud by a cast member, and the play went on.

These are not political plays from a social progressive, nor the product of a rational, skeptical, liberal consciousness, though they are deeply political, as is all of O’Neill’s work. Like many great writers, O’Neill mistrusted the political; he viewed it as a shallow bog in which one risks getting stuck on the way to full, tragic understanding. But his mistrust, his pessimistic genius, and his aesthetic ambitions did not lead him to become a reactionary. O’Neill was a left-leaning liberal manque with a deep respect for the successes of American democracy, and paradoxically an equally deep affinity for anarchism; as for activism, he chose to remain a guilt-wracked observer. His creed and conundrum are articulated by Larry, the fallen Wobbly in The Iceman Cometh:

I was forced to admit, at the end of thirty years’ devotion to the Cause, that I was never made for it. I was born condemned to be one of those who has to see all sides of a question. When you’re damned like that, the questions multiply for you until in the end it’s all questions and no answer. As history proves, to be a worldly success at anything, especially revolution, you have to wear blinders like a horse and see only straight in front of you. You have to see, too, that this is all black, and that is all white.

And later, because O’Neill never missed an opportunity to reiterate:

Be God, there’s no hope! I’ll never be a success in the grandstand—or anywhere else! Life is too much for me! I’ll be a weak fool looking with pity at the two sides of everything till the day I die! May that day come soon!

After All Gods Chillun came Desire Under the Elms (he had the best titles!). He began a new exploration of Nietzsche, read Freud and commenced psychoanalysis. He delved into Expressionism with The Hairy Ape and Dynamo (in which Freud and Nietzsche are recklessly commingled). He wrote bizarre plays, like Lazarus Laughed and Marco Millions; and a play that is both bizarre and beautiful, Strange Interlude. This is perhaps the crest of what can now be understood as a period of intense grappling with strict limitations of theatrical form, its punishing economy of time and cash and audience attention. From this grappling came a surrender to that economy and also a new and deeper mastery of it; perhaps, as well, though I can produce no proof of this, there is in his work a new self-awareness of the significance of his project, the creation of a national dramatic identity. What emerged at the conclusion of this flux was Mourning Becomes Electra (1931).

Mourning is a naked attempt to connect the origins of America and the origins of Western civilization and dramatic art. O’Neill’s true forebear is not Shakespeare, for all that he revered Shakespeare, for all that he wrote poetry when young, but Aeschylus. O’Neill set the play in the region of the country closest to anything this child of a touring, itinerant actor could call native ground: New England, but his personal version of New England, flinty and exhausted. The site of the first European settlements in America, and the setting for Beyond the Horizon and Desire Under the Elms, New England according to O’Neill had become a bloodstained patriarchy, a land of lost grace and Puritan sin—sin revivified and empurpled in the plays by O’Neill’s vigorous apostasy of his parents’ Catholic faith. It was as likely a place as any in America—perhaps the only place—to turn when contemplating the meaning of Origin.