There are only two roads to walk down. There were only ever two choices. You can see the truth—and always be in pain. Or we can look away and be rich. And safe. And happy. — The World of Extreme Happiness

Frances Ya-Chu Cowhig likes to joke that she and Christopher Chen are each other’s doppelgängers. Both playwrights are half Chinese, half Caucasian—Cowhig’s Chinese heritage comes from her mother’s side, Chen’s from his father’s. While Cowhig spent her younger years in China, Chen grew up on the other side of the Pacific in San Francisco.

The mirroring doesn’t end with Asian ancestry. This season, both writers have had plays produced that deal with modern China and the heady topics the superpower evokes, including human rights violations, factory work, censorship and pervasive propaganda. Cowhig’s play The World of Extreme Happiness (playing Feb. 3–March 29 at Manhattan Theatre Club after a run earlier this season at the Goodman Theatre in Chicago) is a realistic exploration of the lives of Chinese migrant factory workers in present-day China, and what happens when one worker in particular has the audacity to change her fortunes.

Chen’s play Caught, which premiered this past October at InterAct Theatre Company in Philadelphia, is a meta-theatrical look at truth versus fiction, taking on such hot-button topics as Chinese political prisons and Foxconn (with references to Mike Daisey’s The Agony and the Ecstasy of Steve Jobs thrown in for good measure). But, unlike Cowhig, his take on the topic is less realistic; the entire play is set in an art gallery.

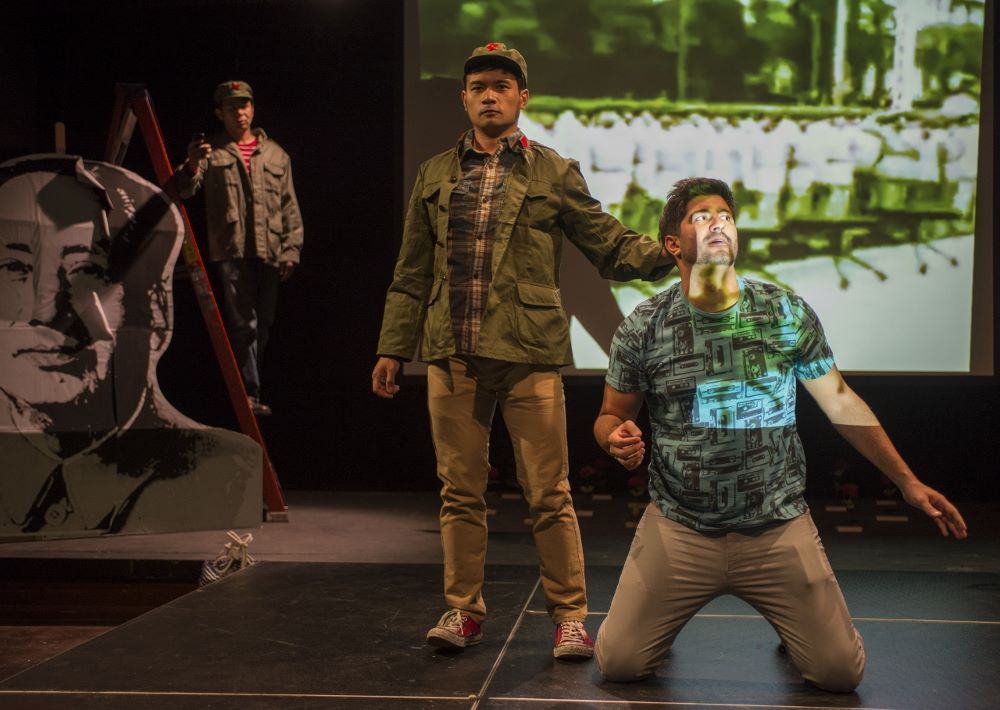

Chen’s previous China-themed play The Hundred Flowers Project was similarly deconstructive, examining what happens when a group of artists decide to create a play about Mao Tse Tung’s Cultural Revolution. The play they devise takes on a life of its own and starts rewriting itself, until what was originally a piece denouncing propaganda becomes propaganda personified. Hundred Flowers had a production earlier this season at Silk Road Rising in Chicago.

Since the two writers find themselves on opposite sides of the country these days—Chen is based in San Francisco while Cowhig, a self-proclaimed nomad, is currently anchored in New York City—getting them in a room together was impossible. Over a three-way Skype video call, the playwrights discussed their fascination with China, its place in their plays, and their individual processes for blending the personal and the inevitably political.

DIEP TRAN: How did the two of you meet?

CHRISTOPHER CHEN: It was through a mutual friend. We got to talking and we just hit it off, like we were long-lost siblings. [To Cowhig] And then you came over and you spent some time here.

FRANCES YA-CHU COWHIG: Yeah, in the summer of 2009, I had a three-week gap between two writing colonies so I asked Chris if I could stay with him at his “writing colony” (San Francisco apartment) and he said yes. And it’s actually while I was staying with him that I met my current partner, Brian, so Chris is kind of the godfather of our partnership.

CHEN: I get your firstborn.

COWHIG: That’s my dog; you can’t have her.

Have either of you spent time in China?

CHEN: Very, very briefly. On a trip with my parents a long time ago, we went to visit my father’s old house in Shanghai. Then in 2009, I was in Beijing for a month working on a play called Into the Numbers at the Beijing Fringe Festival. The play, translated into Chinese, was inspired by [the late author] Iris Chang’s book The Rape of Nanking. That was it. Frances has lived there for an extended period of time, though.

COWHIG: I lived in the U.S. until I was nine. My dad joined the U.S. State Department, and then I lived in Taiwan for two years, Okinawa for two years and Beijing for five years. I was in Beijing during high school, which was right before Beijing got the Olympics bid, so it was a period of crazy change. There were all these dead trees outside our diplomatic compound, so just before the Olympics committee arrived, they spray-painted all the dead trees green. And then after I went to college, my parents moved back to China, Chengdu, for another five years, so I was able to renew my relationship with China through them again.

Frances, your plays look at China in a very realistic way, while Chris, you seem to deconstruct the country in your plays. Where does the fascination with China come from?

COWHIG: For me, it’s just by osmosis—it’s a world that I’ve spent most of my adult life around, through my parents. Because my mother’s from Taiwan, I’ve spent a lot of time in the Taiwanese countryside; her brothers are all in the shoe business. When I was a teenager in Beijing we had several Chinese housekeepers who shared stories about their lives in the countryside. A lot of the great epic stories I was exposed to as a child just happened to be about Chinese people doing incredible things. And since a lot of Chinese writers can’t tell their own stories unless they choose a life of exile, I wanted to commit to contributing a few stories about contemporary China to the theatre.

CHEN: I guess I’m almost the reverse doppelgänger—the exact flipside of that, in that my interest in China has more to do with the Asian-American identity play. I might be more in that tradition, in the sense that, for me, China is still more of a psychological presence. I grew up in San Francisco, which is almost like a multicultural paradise; I went to a Chinese immersion program, from K through 5, where we learned math and science in Cantonese, alongside blond-haired, blue-eyed girls and boys who also studied in Cantonese. And then, of course, there were stories from my father—he was born and raised in China, and he fled the Japanese in World War II, so he lived through a lot of turmoil of the ’40s and ’50s.

I guess what interests me most, when it comes to culture and history, are the parallels between the personal and the epic: How personal psychological struggles will mirror bigger political and social events. I like to look at both in tandem. The Hundred Flowers Project, for example, started by me being really interested in Mao and the Cultural Revolution—I wanted to write a history play. But then I decided that in order to do it in a way that felt true and honest, I needed to somehow reflect my own particular time and place too. So there’s a lot of internal psychology there, too—by that I mean what I’ve absorbed as an American, like a mind warped by social media, stuff like that. My writing is introspective in a lot of ways; one thing that interests me is the process by which race and culture are filtered down into my identity and my psyche.

So China’s always been a presence for me, but it’s a filtered presence.

I don’t want to assume that because you’re both half Chinese, you will automatically write about China. So why do you choose it as the setting for your plays?

COWHIG: I guess a blunt way to answer that is to say that in all my plays I’m interested in trauma and recovery. In my early play [410] GONE—inspired by my brother’s suicide, which happened when I was in college—a young woman goes to the Chinese Land of the Dead to try and make sense of her brother’s death. Something traumatic happens to the main character, and then the question becomes: What now? How does one make meaning when the world as she knows it, her cognitive framework, has been shattered? In The World of Extreme Happiness, I’m looking at the exact same forces, trauma and recovery, but on a national scale—contemporary China, post-Cultural Revolution—a major traumatic event that many Chinese are still recovering from.

When I was living in China, I perceived this huge disconnect between the younger and older generations—like something as simple as my Chinese teacher saying to me, over and over again, whenever she was talking about her experiences, “You don’t understand. You can’t understand.” Or waiting for a bus in the countryside, and when it comes, all the old peasants push past all the younger people to get on the bus. The younger people are shocked and apologizing for their barbaric seniors, but the youngsters have no memory of a time where there was only one bus and if you missed it, you were screwed for the day. So I guess rather than a “national” or “ethnic” landscape, there’s a very specific emotional landscape that I’m consistently interested in.

CHEN: The plays I’ve referenced are all technically set in America. But really I’m interested in the structure of the human mind and how it relates to the structure of society. I’m half Chinese and half Caucasian, so I’m drawn to both cultures and the interplay between them. I do identify as a minority because of my last name and the friends I have—my friends growing up in elementary school and high school were all Chinese, for the most part. So that interplay just comes kind of naturally to me.

COWHIG: That’s funny, because the only place I don’t feel like a minority is San Francisco.

Since you brought up identity plays earlier, Chris, do the two of you see a deviation from what were once traditional first-generation Asian-American themes—of using a play to figure out who you are—versus putting that identity in a broader social and political context?

COWHIG: You want me to talk or do you want to?

CHEN: I can start but I might stop, and we can tag-team. I think what you characterize as ourselves as individuals in relation to the rest of the world is very well-put. I almost think that within my lifetime, I’ve witnessed—and it could be a changing of perspectives as I get older, I’m not sure—the world becoming more global and interconnected.

I guess when I say identity plays, for me, it’s a more complicated, fluid process of me trying to engage with the world and then reacting to what the world gives back to me—a combination of observation and introspection and how they relate to one another. That’s what goes into the dynamics of identity formation for me. As opposed to something like The Joy Luck Club: My parents were harsh, they had this culture A, I’m being exposed to culture B, and there’s that conflict. I think it’s way more complicated now.

I can only speak for myself as a multiracial person. It’s kind of exciting, fun and also challenging to try to grapple with and tackle an increasingly intermingling, multiracial, globalized world.

COWHIG: That sounds sexy.

CHEN: It’s very chaotic but it’s fun chaos! The complexity for me is kind of the point, and how that affects a person’s deeper emotional state and sense of stability.

COWHIG: I think for me my interest in any affiliation to racial or ethnic identity ended by the time I was done with college. Growing up in East Asia, I was always white, an Other, in a very specific way that was very much American. But as soon as I got to college (I went to Brown), suddenly I was the Asian person in the dorm, and people were complimenting me on my English and telling me how exotic I was.

So I went through this whole period of racial crisis and paranoia in college where I was taking ethnic studies classes, taking classes in whiteness, kind of noticing all the racial groupings that were happening on campus, going to the multiracial club. I founded the Hapa club in college. But even that ultimately seemed just like an excuse for poor, alienated Hapa people to talk about how hard it is to be hot and how hard it is to date because they’re so exotic.

CHEN: [laughs] It’s rough!

COWHIG: I love that Japanese saying, “A man is whatever room he’s in.” I continue to experience that in terms of, I guess, constant double consciousness that’s completely dependent on who I’m with and what country or culture I am in.

It became so fluid to me that I became uninterested in it. I think I reoriented myself towards just feeling a commonality with people who exist in the world in some kind of double-conscious existence or identity—people who don’t identify with a singular -ist or -ism, but are kind of more interested in that gray area, or middle ground, or spaces between worlds. That’s kind of where I ended up.

So here’s a loaded question: What do you identify as?

COWHIG: If there’s a box, I check the Hapa box because it’s the most specific.

CHEN: I do identify as a Hapa, but that’s why the question of identity is so tricky, because what does that even mean? And I have been labeled as a Chinese-American playwright, so I have internalized that as well.

COWHIG: I didn’t become a Chinese-American playwright until I started getting my plays produced in London.

CHEN: An Asian-American playwright. [laughs] I forget that means something different in different places.

COWHIG: [laughs] I’m Hapa, though! I don’t know how people see me. I know certainly in marketing terms in London, Chinese American is how I’m often pegged. But because my last name is Cowhig and my first name is Frances, which is androgynous, some people expect a man until I walk into the room. So I have no idea.

Unlike Chris, I have no familial ties to China except in terms of way-back-when ancestry, the same kind that someone whose pilgrim family came over on the Mayflower has to England. My mother’s family is Taiwanese, and has been there for centuries. Sure, you can talk about China as a cultural sphere of influence that expands across Asia and the world, but I am somewhat uneasy with the broad label Chinese-American playwright, because it is usually made in ignorance of these issues, and an assumption that Taiwan and China are culturally identical.

Also the label Chinese-American playwright feels reductive to me, because it glosses over one half of my family history, which is tied to another major migration, that of the Irish into America. My father’s family is Boston-Irish and my childhood, raised around those traditions, foods and stories—many of which are about the generation that fought in Asia and Europe during WWII—have shaped me.

I have no problem with the term Chinese-American playwright, as long as the person using it is comfortable to substitute Taiwanese-American or Irish-American or former Texan, as all those alternative descriptions also describe cultures that have shaped me and that I am indebted to.

Do you think being pegged as something you’re only technically “half” of puts a light on your work that you don’t want to be there?

CHEN: I am interested in all parts of my heritage. I am equally fascinated by my Western side, as well; I’ve written plays that have nothing to do with race. And I continue to write them. Although the plays that deal with China or deal with race seem to get more traction, I’m still holding out hope that the more multicultural we become, the further we progress, the full canon of my plays will be accepted.

COWHIG: When I’m at a theatre doing a reading and someone in marketing or development asks if they can bring photographers into the room during rehearsal, I feel sensitive to whether my play is being exploited to enhance the image of the theatre as one that is committed to “diverse voices.” I’m mainly referring to when the theatre is only doing staged readings and not actually contributing production resources to the actual staging of the play. In those instances, I am concerned that some interpretation of my perceived ethnic identity or the ethnic identities of my actors are being exploited to position that organization in a certain light that helps them get funding that they don’t necessarily deserve, in terms of their actual commitment of resources to these projects.

I think truth in storytelling comes from the writer doing their homework and being rigorous, compassionate and clear-eyed about the worlds they are portraying. Recently, a Chinese writer who had published his memoir in the U.S. said to me that he didn’t want to publish his book in Taiwan because he would have to rewrite it completely for a Taiwanese audience to understand it. This blew my mind and reminded me of how much “culture” and “authenticity” is in the eye of the beholder.

I am against people trying to limit who is allowed to tell what story. Historically, we see over and over in assimilation narratives how mixed-race or culturally bilingual individuals have been used by people in power to conquer, subjugate or colonize one side of the mixed person’s heritage. This usually happens because the mixed person is given some kind of aura of legitimacy or authenticity based on the shade of their skin and not the ideas in their head.

In an ideal world we should be able to evaluate and receive art on its own terms and not need biographical information about its creator to understand or legitimize it.

CHEN: I think for me personally I’ve come to embrace the label of Chinese-American playwright or Asian-American playwright inasmuch as that refers to a specific group of theatre artists. For me the concept of identity is so complicated, and my own notion of the word includes who I am by heredity and experience and how I am perceived by others (for better or worse) because of my last name, and how that does affect who I am and dictate my experience.

And because a certain identity has been bestowed upon me, I do feel a strong sense of kinship with other Asian-American theatre artists who have had similar experiences with labels. I grew up with Asian Americans and I’ve worked with them throughout my artistic career. I was part of Asian American Theater Company in San Francisco and am now part of a new Asian-American theatre group in the Bay Area called Ferocious Lotus; and I was part of an Asian-American sketch comedy group at University of California–Berkeley called Theatre Rice. So I feel a sense of pride in being part of this larger group of artists, because it is a unique perspective, and it’s a new American perspective, and so from that angle I embrace the label.

Getting back to China, it used to be seen by the West as an exotic entity, but now it’s viewed as a competitive world power. Do you find that that perception is mirrored in contemporary works that deal with China—for example, the exoticism of David Henry Hwang’s M. Butterfly versus the stark realities presented in World of Extreme Happiness?

CHEN: Personally, I’m fascinated by that exact topic: How the West views China, how the idea of China is reflected, filtered, refracted into our culture. We like to think we’re in a kind of politically correct, post-racial society devoid of all prejudice.

And yet there’s something about how we view China that’s a little confused and hazy. We have a discourse that’s still in the realm of capitalism and competition. On the one hand, in very blunt terms, pundits will ask, “How do we compete with China, because they are the next superpower? How do we beat them?” And, in the same breath, they will talk about human rights, so the two suddenly become kind of conflated side by side. That’s what I mean by our hazy perception—how the relationship is still conceived of in a weird kind of Cold War mentality.

What interests me, in my work, is the American psyche that does that, as opposed to direct human-rights issues, which I know Frances deals with explicitly. I almost feel that Caught is a complement to Happiness, in a way, because Frances is dealing with real issues in very clear, brutal focus, while I (as someone who’s lived in America all my life) deal with those issues by filtering them in and putting them through the political/rhetorical meat grinder.

COWHIG: When I hear audience feedback [about Happiness], it’s usually interpreted as an indictment of China. It’s really interesting how people see it as an anti-China play when it’s really, I think, equally an indictment of Western capitalism and the “American Dream” idea of bootstrapping.

My cousin in Texas once said, “It’s so great that you’re a writer, because writing is soft power, and we need writers to spread American interests around the world.” And it would be really easy to appropriate my plays, this play in particular, to use as a reason for why China should do this or that, and why things are not working very well in some aspects of Chinese society. But that’s not really the main thrust of the play.

I hope that it’s not interpreted as propagandistic, because what I’m really interested in is complicating every side of the story—telling a story that is very much about all the things we’re seeing in the headlines, but telling it through the lens of trauma and recovery, through the efforts of multiple generations of people who are trying to construct meaningful lives.

CHEN: I hope it doesn’t sound like I was reducing your play in any way, Frances, by associating human rights with it in my gigantic word cloud. I’m more interested, as Frances just said, in the complicated human psychology that underlies events and movements. Understanding is important, and questioning everything. That is probably the first step toward any kind of change on a social level.

When you write about what’s going on within China, do you want to prompt audience members to read up more about it, or work to enact change?

Cowhig: I definitely try to challenge people’s emotions and intellect, and I’m certainly interested in at least challenging the way people contemplate objects: When we hold our iPhones every day, they’re just iPhones, but telling deep, important stories about the people involved in the creation of such objects causes those who hear it to look at their world in a very different way. I’m always trying to illuminate the world through a perspective that’s not usually seen onstage. If you find a compelling way to show a specific minority or disenfranchised world view, that act might be political, because you’re showing a point of view that’s usually white washed or pushed to the margins.

CHEN: I really like what Frances was saying about the act of questioning. I think specifically with Caught, I’m really interested in pushing the questioning. Like once a rift occurs in our mind—like if we’ve read this think piece about iPhones in China and that breaks our perceptions apart—what next? The next step is to examine how our impulses as Americans, our defense mechanisms, will weave these things back together into a safe status quo so we feel good about ourselves, and make us able to kind of ignore what we’ve learned and push it aside. Caught doesn’t necessarily say: Now you must question iPhones again. But it compels you to stop and look specifically at how your mind is re-forming itself, once it’s given difficult information.

COWHIG: I don’t think guilt is a very useful emotion. Any shame or guilt you feel after seeing a play might last an hour—you might feel bad, but I doubt it will lead to meaningful action.

So what helps create change?

COWHIG: Empathy—creating empathy for many different viewpoints, so eventually there is no us/them, no “other.” That is the most useful project of storytelling.