For what would be its third dive into immersive theatremaking, the Denver Center for the Performing Arts’ Off-Center wanted to tackle a fresh challenge: a musical. This experimental, fourth-wall-juking arm of DCPA set its sights on something bold but known, risqué but beloved, and perfect for Halloween: The Rocky Horror Show. The plan was to invite audiences into Dr. Frank N. Furter’s world, recreated in a one-time airplane hangar now dubbed the Hangar—part of a shopping, eating, culture-imbibing space in a former aviation headquarters called the Stanley Marketplace, which had been redeveloped in 2016.

When, in late 2016, Off-Center curator Charlie Miller learned they wouldn’t be getting the rights to the camp classic, he was stuck: He had already assembled much of the creative team when the rights fell through. After some weighty pondering about which scripted musical might lend itself to an immersive once-over—and some enthusiastic nudging by scenic designer Jason Sherwood—Miller decided to take on The Wild Party (composer Michael John LaChiusa and co-book writer/director George C. Wolfe’s version).

“If you can’t do Rocky Horror, you can’t go to Bye Bye Birdie afterward,” said a smiling Sherwood one October afternoon as director Amanda Berg Wilson put the cast of 15 through the paces of a show set in New York during the Roaring ’20s. This was not Jay Gatsby’s version of the era as it unravels in a Long Island enclave but a just-as-fraying mess populated by vaudeville performers, queer poets, and citizens of the Harlem Renaissance. Off-Center leapt from the transgressive of Frank N. Furter et al. to the lubricated excesses of the 1920s, albeit with plenty of gender-bending coupling to be found.

Let’s do the time warp indeed.

The story of vaudeville performers and lovers Queenie and Burrs and their disintegrating wee-hours party had a somewhat bumpy ride when it opened in two different versions, one on Broadway, one off, in the same season. Though nominated for seven Tony Awards in 2000, the LaChiusa-Wolfe show wasn’t favorably reviewed. Inspired by the same briefly banned, book-length poem by Joseph Moncure March, Andrew Lippa’s Party, which opened at the Manhattan Theatre Club, took a very different tack with March’s poem. (Both versions have their partisans, though it’s fair to say that neither is quite canonical.)

The journey of this Wild Party to the Hangar at Stanley Marketplace, which ran Oct. 11-31, reflects the aims of Off-Center and the Denver Center, the region’s largest theatre organization. Launched in 2010, Off-Center exists as a kind of testing center, a theatre laboratory. “Since the very beginning, we have been exploring how to create a more active audience experience that is central to the storytelling and not just a gimmick,” says Miller.

The institutional embrace of the theatrical form has been gaining traction regionally. Off-Center’s first foray with immersive theatre was a production of Sweet & Lucky, created by Third Rail Projects of Brooklyn, N.Y. for DCPA in 2015. As a scripted work being deconstructed, then reconstructed in an immersive setting, The Wild Party was different than Sweet & Lucky. It was also indebted to it.

“I think you guys are really getting it,” Wilson told her cast as they rehearsed “Gin” and “Wild,” two numbers that flow into each other. At the start, Burrs (played by Drew Horwitz) leapt atop a counter in the kitchen of a loft-like apartment that Sherwood and lighting designer Jason Lynch sculpted out of the Hangar’s vast space, complete with a Jacuzzi-size bathtub. He waggled a bottle suggestively, gyrated his hips, and sang the praises of a certain potent spirit concocted in said tub: “If I go mean/If I go mad/Blame it on the gin.” Spread throughout the apartment, the ensemble stomped to the vamping rhythms of a six-piece band tucked away and a piano player in the corner, who was also a character.

Wilson worked in Chicago theatre before relocating to Boulder, Colo., where she cofounded and serves as artistic director of the Catamounts, now in its fifth season. This past summer, Catamounts’ offering was fairly typical of the company’s ambitious, experimental tastes: Dave Malloy’s gypsy punk musical Beowulf: A Thousand Years of Baggage.

In fall of 2016, Miller tapped Wilson for The Wild Party, her biggest gig to date, because she had helmed and performed in “a range of devised and scripted work,” he said. Also “because it was important to have a local director Off-Center could work with to help develop the concept over time,” he says. She’d also gained immersive experience performing in Sweet & Lucky, staged in a warehouse in Denver’s River North (RiNo) art district.

In between repeated run-throughs of the scene, cast members milled about or sat on chaise longues or assorted vintage chairs in various sections of Queenie’s apartment, limbering up or quietly voicing lines. Wilson drove home her ongoing concerns about the audience. “Let’s work on the quality of the interactions, not the quantity of interactions,” she coached.

As with a traditional show, the first job, Wilson said, is “just to stage it, because I knew the second part of this piece was going to be a more nuanced thing we were going to have to take more time with. And we weren’t going to be able to do that until we understood what the primary storytelling was.”

It took about two weeks to, Wilson said, “get the damn thing up on its feet.” She laughed, explaining, “I say ‘damn thing’ because the cast had a bit of vertigo—we got it up so much faster than you would in a traditional work process. Because there was this next layer we had to discover, what I call this sub-scene business.” Had The Wild Party been staged traditionally, she says, there would be opportunities to take characters offstage for a spell.

“With this story, not only did I have to think about what all 15 characters were doing over the course of the entire night, I had to think about it in relationship to the audience, because their journeys were going to be happening in real time, in view of the audience,” Wilson said. “It had to be interesting and engaging if it was going to be visible to a particular audience member. It had to be worthy of being watched, but not too worthy of being watched. That was the challenge—to get the cast to understand that in a way that they could really create meaningful moments that I wouldn’t necessarily have the opportunity to help them hone.”

All the cast and much of the creative team for The Wild Party were local theatre artists, reflecting a compelling mix of newbies and more seasoned practitioners of the immersive form. Sherwood (who has designed three shows for DCPA in 2017, and is designing The Who’s Tommy for 2018) had his first immersive experience designing the Flea Theater’s The Mysteries in 2014 in NYC. Third Rail Projects company member Sean Hagerty designed the sound and Meghan Anderson Doyle the costumes for Sweet & Lucky. In addition to Wilson, The Wild Party’s choreographer Patrick Mueller and actor and dance captain Diana Dresser all performed in Sweet & Lucky.

Musical director David Nehls—who has a home at the local Arvada Center for the Arts and Humanities—came onboard when Off-Center was planning Rocky Horror. In another life, he had originated the role of Riff Raff for the show’s European tour. “Honestly, I was told on a conference call with Amanda and Charlie that we’d be doing The Wild Party and, no lie, I was going to quit,” Nehls admitted. “‘The Wild Party—we’re going to do that?’ It was a bear. I almost ran screaming. I didn’t, and I’m glad I didn’t.”

Still, it was a steep hill to climb. “This particular musical has a reputation as being one of the most difficult musical scores written for commercial theatre,” Nehls said. “So I was thinking, How are we going to take this very dense orchestration, very dense choral writing and put it into this immersive situation?”

A newcomer to immersive work, but an up-and-comer thanks to her work at the Arvada Center, Emily Van Fleet played Queenie with a shaken and stirring cocktail of verve, boozy defiance, and desperation. She recalled her first audition, which was for three roles: Queenie, her best friend and rival Kate, and Sally, a morphine addict.

“They were very clear that this was a production that includes the audience,” Fleet said. “So rather than be performative, it’s really okay and encouraged to interact with the audience. In an audition, that’s terrifying, because you don’t want to look at the people behind the table.” She made it work for her, though: “I hung out at the piano and sang ‘Welcome to My Party’ as if everyone was in a room around me. I think it actually helped me get over some of my weird fears of auditioning. You had to shed that protective wall.”

Fleet credited Wilson for preparing the cast for the experience. “She trained us early on, before we had audience members, with certain language to use—physical body language—but also language to use with the audience to help them understand what was being asked of them, or the type of engagement they’re participating in.”

But it wasn’t until the show went before invited audiences in early October that the performers really began playing with the idea of the audience as a scene partner. “We had several test audiences and previews, and that was extremely helpful in getting the audience on your side,” said Van Fleet. “Queenie is stuck in these battles and conflicts with people, and it was fun to use the audience to back me up.”

Trying to electrify the space between performer and guest, while keeping a semblance of order—and story—was an adventure for both crew and cast.

At an early preview, a female patron came dressed and primed to party. As the show went on, she got louder and louder. She danced and danced. “I had to dance her into a corner,” Wilson recalled. “Oh no, I have to leave?” she said to Wilson. “Yes, you do,” the director whispered back. Consider that gentle expulsion a success.

“Laurence is a good-looking man, so he’s learned how to tactfully handle the propositions,” Van Fleet said, referring to Laurence Curry, who portrays Black, the lovely rake who arrives to the party on Kate’s arm—and who had to field some real-life flirtations from audience members.

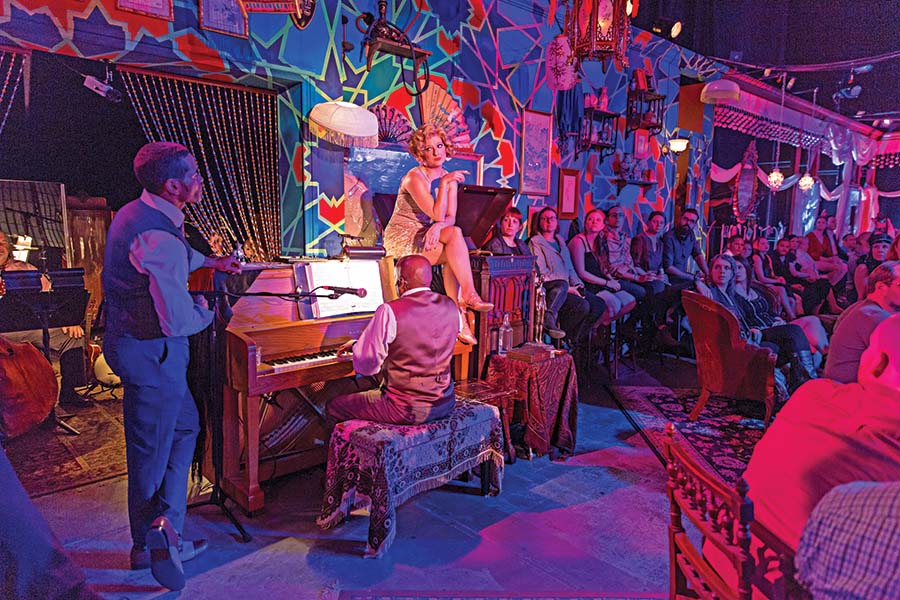

“Part of what we wanted the room to feel like was that there was no delineation between audience member and performer—that once you were in the room, you were a guest at the party,” said Sherwood, leaning against a wall in Queenie’s apartment, where most of the night’s action unfolds. Indeed, the vaudeville dancer’s abode was bigger than many a New York City apartment, with Chinese lanterns, chandeliers, and hanging lights warming the 2,550-square-foot room. Sherwood said they wanted to create an apartment as eclectic as Queenie and Burrs’s crowd, so there were murals and art works, tchotchkes and playbills, photos galore, and rugs—lots of them. The ambience in the vaudeville club, just on the other side of the wall Sherwood leans against, was made to feel similarly authentic.

Sherwood said he sketched out 30 ground plans for an apartment that had to seat 208 guests quickly— and comfortably—while allowing for the slinking, fighting, free-wheeling movements of the 15 actors. The show had a seven-piece band, some of whom entered the action from the pit in a corner hidden by a curtain. Actor-musician Trent Hines, tucked in the corner playing Queenie’s piano, also portrayed one of two very (very) close brothers.

Guests entered from the Stanley Marketplace into a nightclub with tables, two bars on opposite sides, and a stage. The show began with a vaudeville number that wasted no time introducing the night’s hostess and tarnished heroine: “Queenie wazza a blonde,” a man sang. Starting an immersive experience with a fairly traditional come-on—no matter how kinetic—was a bit of intentional bait-and-switch. It was a way to upend the expectations of the attendees, who thought they knew what they were in for because they’d gone to Sweet & Lucky.

“People come in expecting to see a 360-degree musical and they get vaudeville, which is very presentational. And they’re standing there for the first 10 minutes thinking, ‘Really? Is that all we got?’”

For most of the creatives on The Wild Party, it was difficult to talk about the show without mentioning Sweet & Lucky, a show that was as emotionally hushed and luminous as The Wild Party was raucous and dark. It set the bar for audience engagement and pointed Miller and co. in new directions. In Sweet & Lucky, small groups of attendees made their way through a warren of spaces, domestic and otherwise, as they partook in a tender tale of memory and marriage.

“Sweet & Lucky was a game changer for so many people involved,” said Miller. “Everyone who worked on the show was so proud of the final product, especially because it was such a challenge to create, produce, and perform. Because many elements of the show were new to the DCPA—the off-site venue, immersive staging, new marketing strategies, new ways of engaging with audiences before and after the show—the organization as a whole had to approach the work differently, and that helped us become a more nimble operation.”

Off-Center’s follow-up immersive endeavor, the family-friendly adventure comedy Travelers of the Lost Dimension—a collaboration with the local improv troupe ACE—wasn’t as artistically daring. But it did help Off-Center forge a relationship with the Stanley Marketplace, whose chief storyteller Bryant Palmer counted himself among the Sweet & Lucky converts.

“One of the reasons this collaboration works is because we have a belief in and understanding of Off-Center’s vision and they, I think, have a belief in and understanding of ours,” said Palmer, who recalled the first time he showed the space to Miller and his then co-curator Emily Tarquin (now at Actors Theatre of Louisville). “We were piles of dirt and a bunch of concrete. It looked like nothing.” Who better than theatre folks to see the possibility in an empty space?

Of course, there’s empty and then there’s empty. Off-Center expended a great deal of resources just readying the 16,000-square-foot warehouse it transformed for Sweet & Lucky: adding a ramp for accessibility, fixing a bathroom, getting the permits and licenses needed to occupy the space (including a liquor license), and more.

“Based on our learning from Sweet & Lucky, we wanted a venue that was already set up and could allow us to focus on making the art,” Miller said. “The Hangar is the perfect big blank canvas for us to work in, and it comes already set up to host large crowds (and with a liquor license). The less you have to put into the building, the more you can put into the art.”

The Wild Party further tested the waters for an institution set on identifying and growing a younger audience that will buy into its eclectic endeavors. In 2015, Off-Center was one of 26 organizations throughout the nation to receive a Wallace Foundation Building Audiences for Sustainability grant, a four-year commitment that encourages arts organization to develop programming strategies for building a specific audience. “Our target audience is Denver millennials, a large and growing population of 18- to 34-year-olds that the DCPA sees as a vital demographic to engage in the present in order to ensure the organization’s future,” said Miller.

Off-Center launched a Kickstarter campaign in July. The crowdfunding call—587 backers pledged $27,521—was less an example of a deep-pocketed institution pleading poverty than a way, said Miller, of “generating ambassadors and allowing people to be a real part of what we’re doing. While the DCPA is a big institution, this type of immersive work goes above and beyond our mainstage programming, and the Kickstarter campaign allowed us to not only generate funds that we actually needed to produce the show, it also helped us engage with nearly 600 backers, most of whom do not otherwise donate. These patrons are invested.”

On opening night, women arrived wearing long strings of faux pearls, feather boas, and flapper dresses. Men came clad in smoking jackets and, yes, some had boas too. Half an hour before show time, the bartenders in the ersatz vaudeville club were busy pouring cocktails concocted for the occasion—the Dewdropper, the Live Wire, the Bourbon Breezer—along with gallons of “bubbles.” The coat check guys and gals stayed busy.

After a bit of Burrs’s serrated comedy routine and a nasty quarrel between the lovers, the audience was shepherded with casual, flirtatious purpose into Queenie’s place. The apartment filled smoothly, and with drinks in hand, friends near, guests talked and gawked like they might at any party. Guests could prickle with anticipation the way they might at the start of any show, while being oddly aware that the show had already begun. We were in the midst of it, yet ready for a theatrical bash just the same.

Already edgy and extravagantly annoyed with each other, Queenie and Burrs then hosted a soirée that was biting and vivid, full of intrigue and brash music. An intermission—the only deviation from the Broadway script—allowed people to snoop, belly up to the bar, and reconfigure their vantage points in a congenial, musical-chairs sort of way.

Strike that: Given what takes place in the second act, it was more like rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic. The mood in Queenie’s apartment turned ugly. Guzzling gin and snorting cocaine will do that to a person. If it was exhilarating to be next to a singer belting a tune, or sitting at a table when the zombie-like Sally comes alive, it was unnerving to be near an increasingly physical quarrel, and still more disquieting to be in the proximity of sexual assault.

Interestingly, this immersive restaging didn’t elicit the same critical contempt and frustration that Broadway’s Wild Party had. (The New York Times’s Ben Brantley called it “a portrait of desperation that itself feels harshly, wantonly desperate.”)

“I saw the production on Broadway. Twice,” musical director Nehls said. “And it was one of my least favorite things—ever. It’s another reason I wanted to run away screaming. Now I see that taking that piece, which was so unlikable, so arch and cold and distancing, and then putting it in this arena where it has to be approachable—I hate to sound cocky, but I think we may have improved it.”

It might be fodder for future graduate theses: whether being in the midst of a devolving party is better than watching it from the mezzanine. Local critics seemed to think so.

“The gin is cold and the music’s hot, as they say, the performances are worthy and the full effect makes a good case for experimenting beyond conventional proscenium theatre,” wrote Joanne Ostrow in the Denver Post.

“The direction is skillful, and the performers, led by Emily Van Fleet’s electrifying Queenie, have the strong voices and charisma necessary to dominate the room as the action moves from scene to scene,” Juliet Wittman stated in Denver’s alt-weekly Westword. “The only problem is that sometimes you hear a voice and simply can’t see whose it is for a few minutes because your view is blocked by a pillar or someone’s head. Still, in a way this adds to the veracity of the event: How often have you been at a party and heard raised voices coming from a corner or the hallway outside and tried to figure out just what was happening?”

Early audience surveys conducted by DCPA leaned toward the enthusiastic, with the show receiving a score of 8.7 (out of 10) rating. Some, though, wished The Wild Party had been more immersive: “We also attended Sweet & Lucky last year and Then She Fell in NYC by Third Rail Projects,” wrote one respondent. “Both of those shows were much better interactive theatre experiences and truly brought the audience into a different world and on an emotional journey.”

A deluge of bathtub gin may have done irreparable damage to Burrs and Queenie’s relationship, and sent their impulsive shindig into a tailspin. But Off-Center’s commitment to fluid, immersive storytelling appears to be on the ascendancy. Denver audiences’ reaction to The Wild Party might be likened to the guests’ demands at the Prohibition-era party: Let it flow, let it flow, let it flow.

Former Denver Post film/theatre critic Lisa Kennedy writes on theatre, film, books, and culture. She has written for The New York Times, Newsday, CNN Opinion, and Essence magazine.