Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, the old saying goes. It may be true, but it doesn’t pay the bills. And in theatre, blatant imitation isn’t flattery—it amounts to theft of an artist’s intellectual property. Production photos, fight choreography clips, even bootleg production videos are often just a Google search away. While it’s never been easier to copy someone else’s work, it’s also never been easier for directors and designers to find potential offenders.

In 2015, for instance, Detroit-based set designer Monika Essen had a colleague alert her to Facebook photos shared by a local community theatre company. Why? Because the company’s set appeared to be a replica, down to the style and positioning of its furniture, of one she’d created for a 2005 production of Ice Glen at Ann Arbor’s now-defunct Performance Network Theatre.

“It wasn’t as well crafted or as well painted, but the concept was exactly the same,” said Essen. “I called the person in charge there, and at first she denied knowing me or seeing the show. But it’s not like [the design] came from the script. It was an abstract concept I came up with. It’s not like it was a realistic set that had the same moldings and color scheme.” Essen then recalled the person on the phone backpedaling yet again, before admitting that “maybe she did see it at the Network years ago, and subconsciously she must have thought about it when doing the design.” To which Essen responded, “You have to pay me, or you’ll be in a world of trouble. I will shut your show down.”

In the end, the company agreed to pay Essen the union rate for her design, though the whole experience left a sour taste in her mouth. “When I looked at those photos, I was shaking, I was so upset,” she said. “It doesn’t matter if you’re a community theatre or professional.” Had Essen met with greater resistance, she would have contacted her union, United Scenic Artists 829, for more support. But for her, it wasn’t just a matter of income loss. “It’s not just the time it takes to research and design and create something. It’s like part of your soul, so it ends up feeling like someone stole part of your soul.”

Amateurs and professionals alike have in recent years faced a sharp learning curve regarding where the line between “inspiration” and theft lies. For decades, community theatre groups have worked hard to unabashedly mimic the best or most iconic productions of shows on a microscopic budget. And professionals have tried to balance artistic risk with the urge to satisfy built-in audience expectations (i.e., gold top hats and tails for A Chorus Line).

“What [audiences] are often looking for is not something original, but a slice of that iconic work, so there has always been, and will always be, that layer,” said Laura Penn, executive director of Stage Directors and Choreographers Society. “What we’ve become more aware of, maybe because of technology, is how common [copying] is, and what we’re trying to do is set the tone. We encourage original work, but if you want to try to replicate a Broadway show, there are ways to do that. You have to ask permission.”

In terms of licensing, stage directions, annotations, prop lists, and floor plans that in a previous era might have been included with a script are now almost never part of the standard package, largely due to SDC’s work with publishers to make this change. “In some old scripts, they have them, because the authors had obtained that, and designers back then didn’t stop and say, ‘Hey, that’s my work, I deserve compensation for that,’” said Samuel French executive director Bruce Lazarus. “We are really diligent advocates for playwrights’ rights, and because of that, it would be disingenuous of us to not also be advocates for others that make theatre happen.”

Tony-winning choreographer Jerry Mitchell is Musical Theatre International’s first collaborating partner for a new offering called the Original Production, which licenses and provides online instruction for groups and companies that wish to use a recent show’s original choreography. (Some long-established chestnuts, like Fiddler on the Roof, have always offered choreography instruction and licensing as an option.)

“There’s the important question of education about this,” said Howard Sherman, who as head of the Arts Integrity Initiative has often written about issues of censorship, plagiarism, and appropriation. (Sherman now serves as director of communications for SDC.) “We should not be about vigilante justice. The real question is, what are people being taught or absorbing about what is the proper practice? What is occurring in people’s training that made them not understand that this is both illegal and disrespectful of fellow artists? We’re living in the era of sampling, the era of information that we want to be free. But that’s antithetical to the ability of creators to be paid for the work they’ve created.”

What happens when sampling goes amok? One instance arose in 2016 between two Equity houses, Trinity Shakespeare Festival and Dallas’ Lyric Stage. Set designer Bob Lavallee created an enormous tree as the centerpiece of TSF’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and Lyric producer Steve Jones reportedly reached out to Lavallee and asked if he’d be willing to adapt his set for Lyric’s Camelot. Lavallee declined, but said Jones could use the tree for a $200 fee and a program credit.

Precisely what happened next, in terms of the logistical breakdown, is a mystery to Lavallee (and an email sent to Jones went unanswered). But when reviews for Camelot started appearing, Lavallee noticed that additional set pieces from Midsummer had been repurposed, including a large round platform and a doorway with its own drapery and wagon (which docked to the platform). “I really don’t know how the entire set ended up over there,” remarked Lavallee.

What’s more, the set designer in the Camelot program was listed as Cornelius Parker, an unfamiliar name with no bio in the program. “I kept thinking: Who is this designer that would put his name on someone else’s stuff, paint it gold, and call it his own?” wondered Lavallee.

A colleague suggested to Lavallee that Parker could be a pseudonym, which proved to be correct. Jones had also used the Parker pseudonym for a 2015 production of Lady in the Dark, for which he gathered set pieces from Lyric’s storage. (“I didn’t want to take credit for it,” Jones had told TheaterJones, a local arts publication.)

Lavallee, who isn’t a member of a union, didn’t pursue any legal action then. According to Sherman, that’s not surprising: “When someone has to [take legal action] alone, these designers, who are barely paid in the first place—it’s hard to overstate how difficult that is for someone in that position.”

The story has a somewhat satisfying coda: At that year’s Column Awards in Dallas, both Lavallee and Cornelius Parker were nominated for best set design. “It seemed like a comment they wanted to make,” said Lavallee. “This is a small town, in terms of the theatre community. People knew what was going on.”

When it comes to copyright infringement, playwrights and designers have more legal protections of their work, in part because their contributions have more clearly defined boundaries, and thus lend themselves more easily to documentation. For directors, it’s a different story.

The three marquee cases involving directorial infringement have ended in settlements, so no legal precedent has been set. A case involving Gerald Gutierrez’s 1992 Broadway production of The Most Happy Fella, seemingly reproduced (structurally and otherwise) in a theatre near Chicago in 1994, ended with a negotiated, undisclosed payment and a public acknowledgment of Gutierrez’s “contribution.”

Joe Mantello’s acclaimed 1994 Off-Broadway (and later Broadway) production of Terrence McNally’s Love! Valour! Compassion! was subsequently exhaustively copied by Boca Raton’s now-shuttered Caldwell Theatre Company, which led to the first copyright ever granted to a director’s annotated script, as well as a settlement of $7,000, donated by Mantello to SDC. As a first point of proof in that case, though McNally’s script begins with the words “Bare stage,” Caldwell’s production instead opened with the show’s male characters, assuming specific postures, positioned around a dollhouse on a green mound—precisely the way that Mantello’s production began.

Finally, in 2006, John Rando, director of Urinetown on Broadway, joined with choreographer John Carrafa—as well as with the show’s set, lighting, and costume designers—to sue the Mercury Theater in Chicago and the now-closed Carousel Dinner Theater in Akron, Ohio, for copying the Broadway production’s design and directorial choices. Both regional companies paid the Broadway team an agreed-upon (but undisclosed) sum. An actor from the Broadway production, Jennifer Cody, directed the Akron production, and her co-star husband, Hunter Foster, defended her in a statement published by Playbill, disputing that the show copied Rando and Carrafa’s work and instead asserting that the Akron production did nothing more than maintain “the spirit of the show.”

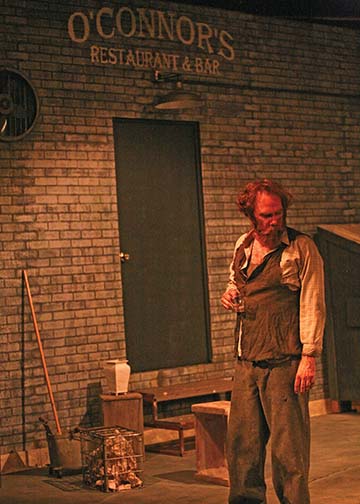

Directorial choices such as blocking or production concept continue to occupy nebulous ground legally. And that’s the basis for an unresolved, still fraught contretemps between Chicago-based actor/director Hans Fleischmann and Bay Area artistic director Craig Miller. In 2012, Fleischmann staged The Glass Menagerie via the Mary-Arrchie Theatre Company in Chicago. He had been inspired by a long stretch of time when he lived in his van in Los Angeles, so he played Tom as a delusional homeless man who lived in a city alley beneath a fire escape.

And the menagerie became broken bits of glass—approximately 3,500 pieces of it, collected from local bars. “I was spending 12 hours a day at the theatre,” Fleischmann recalled. “And I was also the technical director, so I got to a point where I was just basically moving every little prop two inches around the set until everything looked perfect.” He adds. “It was like an art project, in a sense.” Fleischmann’s production made a big splash, and the Chicago theatre community took notice; one colleague even told him, “You’ve ruined The Glass Menagerie for Chicago.”

In 2014, on the other side of the country, Miller (per his own account) drew on the immediate surroundings of the 6th Street Playhouse, a “semi-professional” theatre where he works as artistic director, to hatch a similar vision of a homeless Tom Wingfield, fire escape included. Miller explained that 6th Street is known as the “homeless highway,” with an overpass that’s home to a sizable encampment, and a mission and soup kitchen nearby. “The scenic design was completely inspired by the east stoop of our building, where daily I watch homeless eat, sleep, drink, smoke crack, scream and talk at nothing and no one, and also defecate and urinate, and vandalize at times,” he wrote in an email.

After photos of Miller’s Menagerie appeared online, Fleischmann spotted them and consulted an attorney. “He said, ‘I hate to say this, but you have no legal rights in this situation,’” Fleischmann recalled. “You can’t copyright an idea.’ That was the worst. I feel like such a victim.”

How might the alleged theft have occurred? Miller has Chicago ties, but he left the city in ’99. He also graduated from the same college as Fleischmann (Illinois State University, albeit with a decade between them). They also share a number of Facebook friends in common. According to Miller, though, he’s now “far removed” from Chicago’s theatre scene, and said he’s on Facebook only about once a week to market the Playhouse’s shows, “and almost never for personal business.”

The similarities were also not lost on the theatre community on both sides. Where the law failed, the court of public opinion ruled in favor of Fleischmann. Sonoma County, Calif.-based actor/director/critic Harry Duke published an online essay noting the similarities between Menagerie productions (and casting some doubt on Miller’s account). Chicago playwright Ike Holter wrote a no-holds-barred Facebook post condemning the 6th Street production, writing, “Element by element lifted directly from hardworking people in my city.” The post also listed Miller’s email address twice and urged people to call him out: “Just send something now to Craig Miller. Cry Foul. Declare shame.”

“When Ike Holter blew the horn on this, people went to war,” said Fleischmann, who appreciated this swell of support from his community. “To know that it mattered, and that a group of people, young people actively controlling the pulse of Chicago theatre were coming to its defense was really comforting.”

Miller called the accusations, and resulting online beatdown, “the single most awful experience of my professional theatre career,” he said. “I lost friends and colleagues, and a dark cloud came to live over me and my theatre for a long time. I have had to work very hard to regain trust that I lost for absolutely no reason other than bad timing of a similar production concept.”

He also said that when he tried to explain his side of it, “I was immediately shamed for being an opportunist—for exploiting the societal issues of the homeless in defense of my stealing. I realized very quickly that nothing I said to Mr. Fleischmann or his supporters would be truly listened to.”

And while Fleischmann would later restage Menagerie for the Hypocrites theatre company, Miller almost ended his theatre career. He considers himself a defender of intellectual property, saying, “I was a theatremaker for a long time before the accusations three years ago, and up until that point I was the one proudly crying ‘bullshit’ whenever I saw it happening. I never thought I would have ‘bullshit’ called on me when it wasn’t the truth.”

Could these wounds have been avoided if legal protections for directors were in place, and both artists could have their say in court? Perhaps. But the act of creation is such an intensely personal one that feelings would likely still run high.

Renowned director Anne Bogart, a member of SDC’s executive board, once said something to Penn on this topic that has stuck with her. “Artists are always going to be influenced by other artists, but what Anne said to me was, ‘It’s what you do with the inspiration,’” Penn said. “So we’re all inspired by each other, but it comes down to how you transform that inspiration.”

Jenn McKee is a Michigan-based freelance writer and a former staff arts reporter/critic at The Ann Arbor News.