This feature was first published in our November 2013 issue; we’re reprinting it here now, as the New Play Exchange is just days away from its Jan. 15, 2015 launch. – Editors

Like many playwrights, Gwydion Suilebhan has long been frustrated by what happens after he has written a play.

“The task of figuring out, among the thousands of theatres across the United States, which ones might be both right for a given play of mine and interested in considering new work at any given moment in time,” he says, “falls somewhere between onerous and impossible.

“No one person knows the theatrical landscape well enough to target submissions effectively every time,” Suilebhan continues from his home in Washington, D.C. “Despite your best efforts, you occasionally submit work to theatres for which it isn’t really appropriate, or theatres that aren’t considering submissions anymore. And, on the flip side, you miss opportunities, too. It’s a terribly imperfect system, full of bugs.”

That’s why Suilebhan is delighted by the idea of a national database of new plays—an idea, in fact, that promises to be coming soon to a theatre near you. Indeed, Suilebhan was hired this past summer as the director of the New Play Exchange, an online tool being developed at the National New Play Network, aiming to be fully operational by 2015. “It should be a genuinely disruptive technology,” says the playwright—and he means this in a good way.

Julie Felise Dubiner is also looking forward to such a database—one that is truly national, and completely open. Dubiner has worked with many electronic listings of plays over the course of her career as a literary manager and a dramaturg, but they were databases from individual theatres, and they were part of the process that she hated.

“I was constantly lying to writers,” complains Dubiner, who currently works as associate director of American Revolutions, a play-commissioning program at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival. “I would lie about how submissions would be handled, how and why plays were selected, what I signed my name to in a rejection letter, and even on coffee dates.” Some of this dissembling could be attributed, at least indirectly, to the nature of the databases themselves, which were closed to all but a few staffers.

“In many cases, I found that our reports on plays were quite short and quite cruel, and we would have died a million times if a writer had seen what we said about the play. But we shoved it in a system, never to be seen again, and sent a pretty useless and lying form letter.” This approach persisted in part, she says, because it “allowed my bosses to count how many plays I had ‘processed.’ I found that oppressive and immoral, and also powerfully antithetical to the dramaturg’s job of supporting and promoting artists.”

Dubiner’s bottom line: “We’ve all gotten very nice—and to me, nice is not the same as kind. And it doesn’t make for good art.”

Last year, Dubiner wrote for the HowlRound website a “manifesto on the 21st-century literary office.” The first item on her agenda: “We all have the same pile of plays sitting on our shelves, in our e-mail, on our devices, and on the floors of our offices, homes, and cars. Let us call for an end to submissions as we know them now. Let us call for the creation of a national database for new plays,” an accessible archive in which information could be shared.

What she didn’t know at the time was that people had already been working on just that. For a long time.

When Suilebhan is asked why there’s suddenly so much interest in a national database of new plays, he has a reply ready.

“It’s not sudden at all,” he says. “I have personally been writing and thinking about various versions of the New Play Exchange for years. I consulted on a similar project for the Playwrights’ Center [in Minneapolis], and I talked about it with anyone and everyone who would listen. And there were lots of people doing the same thing.” The New Play Exchange, Suilebhan says, “is going to be an evolutionary leap from its predecessors. But it does have a lineage.”

One such predecessor is Doollee.com, born in 2003 when a British accountant named Julian Oddy taught himself html coding by putting his wife’s collection of plays into a database. The project, which remains Oddy’s personal hobby, has grown massively: He began it with 3,093 playwrights and 8,146 plays, as he explains on the site, and since then has been “adding approximately 39 plays and 11 playwrights per day. We aim to list every play written or produced in English since 1956.”

For years Literary Managers and Dramaturgs of the Americas had organized a Script Exchange, publishing 35 issues that included reviews from their members nationwide (and beyond) of more than 1,000 new plays. Recently, they decided to reestablish the exchange—and then learned of the planned New Play Exchange. They have become one of the National New Play Network’s partners in the project.

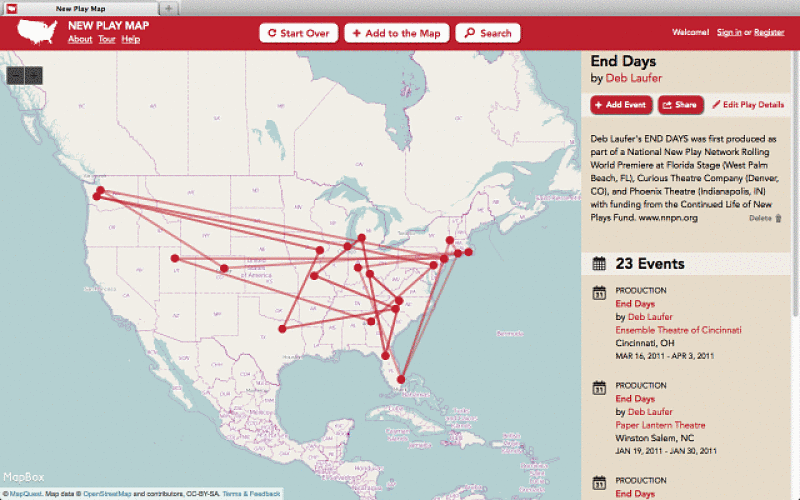

And then there’s the New Play Map, a straightforward list of “events” (plays that are currently running) and dots on a map of most of North America showing where they’re happening. Typically, an “event” is an opening of a play, or an indication of a current run. Judging by the last day I looked, when there were just 28 new plays listed as running in all of North America, the site has not yet reached its full potential.

The New Play Map is a project of HowlRound, the theatre think tank now based at Emerson College in Boston. Here is how HowlRound director Polly Carl describes the map: “The project aims to visualize the ‘how’ of how a new play moves from idea to development to production. It seeks to show the enormous amount of new-play activity. It is also a result of a huge database of information that we’re exploring possible uses for.”

The idea for the map began in 2009, inspired by such group projects as Wikipedia, and was launched in 2011, when HowlRound (under a different name) was under the aegis of D.C.’s Arena Stage. As with LMDA’s Script Exchange, HowlRound is partnering with the National New Play Network to see how the map and the exchange can fit together.

The idea for the map began in 2009, inspired by such group projects as Wikipedia, and was launched in 2011, when HowlRound (under a different name) was under the aegis of D.C.’s Arena Stage. As with LMDA’s Script Exchange, HowlRound is partnering with the National New Play Network to see how the map and the exchange can fit together.

So it may not have happened overnight, but why is it all coming together now?

“We have created a huge infrastructure in the theatre field with many redundancies,” Carl suggests. “Our hope with using technology to the benefit of theatre is to create a more efficient infrastructure and free up more resources for artists as a result.”

These previous efforts at collecting plays in one place, in Suilebhan’s view, “simply replicate what we’re already doing offline. Instead of storing plays alphabetically in filing cabinets, we keep them in structured databases like Doollee; instead of submitting plays by mail, we submit them into virtual in-boxes. The online tools we’ve seen are a bit more efficient, but they’re simply manifestations of the same offline ideas.” By contrast, he boasts, the New Play Exchange “will represent a paradigm shift.”

Some of the elements that will set the new exchange apart:

- Full scripts, tagged. A playwright will submit a script, provide background information (a synopsis of the play, a link to a website), and tag the script according to such criteria as cast size, genre, region and subject matter.

- Theatres, tagged. At the same time, the script-readers at each theatre will create a detailed profile and tags that apply to their theatres (region, size, aesthetic) and what they’re looking for. The National New Play Network is thinking of ways, in imitation of social media, of keeping users on both ends engaged in these entries, by allowing them to post updates if, for example, there is a new production or new reviews.

- Public recommendations and assessments. The network is calling this crowd-sourcing, and comparing it to the kind of recommendations you can see on Netflix. But a user can select whose recommendations to pay attention to, employing a filter that will supply only those comments by specific trustworthy recommenders, for example.With data sorted along these lines, the play exchange would be able to supply a quick answer to such complicated requests as: “Find me the 10 most-recommended, unproduced comedies by playwrights of color.”

Dubiner sees the potential in such a system, but warns that it will only be as good as the contributors make it.“Those of us who populate it with reports and recommendations should be honest,” she says. “Lifting the veil should keep us from being cruel. Writers likely will face some truthful opinions about their work that may in some cases be difficult, but in my hopelessly optimistic heart I dream that it will allow for more fruitful and direct conversations between literary staffs, theatres, agents and creators.”

Playwright Adam Szymkowicz, who has interviewed more than 600 playwrights for his blog, typically asks each one: If you could change one thing about theatre, what would it be? Brian Polak, a playwright who also works as the marketing/communications manager for the Theatre at Boston Court in Los Angeles, gave a succinct answer: “It is logistically impossible for theatres to have an open submission policy. There are too many plays and not enough time to read and consider them all. I would like to change that.”

So, will the New Play Exchange be the agent of that change?

“I hope it will lead to playwrights getting their plays in the right hands and theatres finding exactly what they are looking for,” Szymkowicz says, then adds: “I guess we won’t know until it happens.”

Jonathan Mandell, a frequent contributor to this magazine, tweets as @NewYorkTheater.