Ask now the beasts, and they shall teach thee.

—Job 12:7

When we talk about critics, we tend to talk about “criticism.” We don’t differentiate or categorize; we treat all of it as a nuance-free lump. But the act of labeling can do some wonderful, mysterious things. The great reviewer-director Harold Clurman wrote that “the primary obligation of the critic is to define the character of the object he is called upon to judge.” Another way of putting it: When you’re in Eden, marveling at Creation all around you, the first job is naming the animals.

In that spirit, here is a partial list of critical types. Of course, a critic might spring from one form to another as the moment calls for it; in fact, hopping boundaries is something theatre critics tend to do a great deal. Plenty of surprising people have swashbuckled their way over to theatre criticism and done their part: Edgar Allan Poe, Walt Whitman, Henry James. (Between you and me, even St. Augustine dabbled.) If theatre criticism is to live and grow, each of these categories needs new writers—needs more writers.

The Contextualizer

Theatre is, of course, a wonderful lens to hold to the eye to look at the world around you. It is an ensemble-made event, designed to be experienced in public. If you watch it carefully, you can see each performance signaling us about society, the culture, our politics, the other shows around it, the economy, the globe. Contextualizers are anthropologists; their antennae stretch out beyond the theatre proper and register the weather outside.

My first and favorite of these is William Goldman’s rollicking, perceptive book The Season. If I ever make money at this career, I’m going to put a copy in every hotel room in the country. My old favorite Wilfrid Sheed’s gorgeous, capacious reviews always pointed outward; you can actually read him as a civic philosopher. And of course Clurman—eminence grise of the Group Theatre—wrote about plays in a way that penetrated deep into our tangled network of American attitudes. His legendary review of A Streetcar Named Desire (“It is the substance—not the conclusion—of an argument that gives it validity”) analyzed text, performances, and direction with the productive curiosity of Malinowski among the Trobriand Islanders.

Contextualizers need time to sit and think, time to look out the window or to wander the streets. In other art forms, they are in full sail: Emily Nussbaum on television, Wesley Morris and Mark Harris on film, Jason Zinoman on comedy, Alex Ross on music. It seems crazy that in the theatre, of all places, the very form that encourages its audience to think “the long thought,” it has become hard to find time to write in a way that thinks “long” in its own right. There’s not enough space to expound in most print coverage now, of course. But we also have the mistaken idea that, outside of Hamilton, theatre is a niche event and thus isn’t part of the wider cultural conversation. To rebraid theatre into everyday American life, we’ll need to price every seat on Broadway and Off Broadway at $40, send out nationally funded tours of Pulitzer Prize- and Obie-winning plays, fund performances in schools, and revive our sleepy art.

Till then, thank heaven, we still manage to have minds like Jesse Green and Laura Collins-Hughes in The New York Times and Alisa Solomon in The Nation. We could use some more.

The Diarist

Some of the greatest critical writing about life with theatre in it—as opposed to the theatrical life—comes from diarists. The most famous is Samuel Pepys, whose diary is equally delightful when he’s suffering from kidney stones (and the, er, intimate surgery he receives without anesthetic) and when he’s seeing Shakespeare plays.

Gems are lying all around in Simon Gray’s superbly funny diaries, and the British critic James Agate published multiple volumes of his recollections, called, adorably enough, Ego. You won’t find better epigrammatic theatrical thinking (“Shaw’s plays are the price we pay for Shaw’s prefaces”—rimshot!) anywhere. In his journals, Thornton Wilder speaks wonderfully about Shakespeare, “one of the few writers in all literature who could present a young woman as both virtuous and interesting,” and his letters reveal a man always on the threshold of theatrical revelation.

Sadly, this too is a category that’s dwindling from under-population; diary-keeping has gone out of style. Still, Sarah Ruhl’s beautifully clear 100 Essays I Don’t Have Time To Write has some of this private, daily, speaking-to-herself quality. Just her essay on twins alone—it’s about a page and a half—has changed forever how I see children in plays.

The Encyclopedist

The encyclopedist names the categories, distinguishes the genres, coins the terms. The very first of our tribe was Aristotle, a philosopher and biologist, a taxonomist in every way—and his work shaped all that came after. Henri Bergson defined comedy (“an anesthesia of the heart”); Joseph Addison defined wit; Brecht defined alienation. Martin Esslin collected certain writers into his concept of the Theatre of the Absurd, and it persuaded us to read theatre as philosophy; Denis Diderot described “the fourth wall” and wham! We saw what we’d been peering through for a thousand years.

My own favorite is C. Carr, the Village Voice critic who chronicled Downtown New York at its zenith in the ’80s—you can read her collected works as a history-in-installments, a cool-headed catalogue of performance and its ramifications.

Writing now, we have blogger Jeffrey M. Jones, who coined the term “gauge” theatre; Karinne Keithley on “hole poetics”; PAJ’s Bonnie Marranca (the Theatre of Images); and the great dramaturg and scholar Marc Robinson, who has been methodically shaping the “other” American canon, which includes Mac Wellman, Suzan-Lori Parks, and María Irene Fornés.

But alas: Encyclopedists are endangered. For the most part, they have taken shelter in academia, where pre-tenure incentives work against writing for public engagement. There are exceptions, like, say, the brilliant David Savran. Yet, in large part, theatre’s best thinkers tend to write for each other, to speak mostly at conferences, to write in the codes of an increasingly jargon-heavy field. (Not all new definitions are useful.) This in turn leads to the increasing academicization and intellectual segregation of theatre. What was supposed to be a refuge may have been a trap.

The Impressionist

Since we’re being careful about distinctions, there is a difference between theatre critics (who address a performed event) and drama critics (who write about the text). But even many theatre critics weight their writing toward a discussion of the script, unpacking dramaturgical decisions and keeping the playwright at the center of her focus.

The impressionist’s skill, on the other hand, lies in describing the physical moment, the gesture, the performance—the thing that happened that can’t be kept in a notebook. For an example, go read Walter Kerr’s description of Irene Worth’s exit from Andrei Serban’s 1977 Cherry Orchard—you actually experience her exhilaration as she walks…then runs…then races around the room.

Some actors have their specific chroniclers: The barnstorming stylist Kenneth Tynan had a special ability to describe Laurence Olivier, for instance. Or here is George Bernard Shaw blissing out on Eleonora Duse: “You are welcome to…count whatever lines time and care have so far traced on her. They are the credentials of her humanity. The shadows on her face are grey, not crimson; her lips are sometimes nearly grey also…” You can hear him being ravished by her unpainted beauty, word by word.

These days, we critics seem to be rather less bewitched by performers’ physicality, which is a shame. As Alec Guinness once wrote (rather tartly), “Dramatic criticism requires the gift of conjuring up for the reader a visual picture of a performance.” Have we forgotten this, amid the internet blizzard of 10,000 memes a day? Perhaps we critics think that the big picture at the top of the page will do our describing for us, or perhaps it’s that old bugbear, the limited word count. It’s not surprising that today’s greatest impressionists are nearly all from the dance world; their specific brief is to convert motion into text. For this, read Joan Acocella, Siobhan Burke, Eva Yaa Asantewaa, Gia Kourlas, Wendy Perron. All are masters.

The Inwardist

You can date a critic by a) counting her rings or b) seeing how long she waits in a review to weigh in with an “I.” In the para-journalistic ’90s and ’00s, theatre critics would wait to unleash the subjective “I.” If they had to use it, they deployed it only at the end of a review, once all the “objective” work had been done.

But the internet, with the immediacy that seems like intimacy, has shifted the way we think—and, by extension, the way we consume thinking. We are still in the heyday of the personal essay and anecdotal revelation, and inwardists write their criticism in this key. The main relationship the inwardist is describing isn’t necessarily the one between play and play or even play and audience. Instead, the inwardist does her deepest research on herself.

In the case of a writer like Pulitzer winner Hilton Als, the conversation can be between the play and the ideas of the philosopher or novelist uppermost in his mind. Some look even further in. The late Jill Johnston, the full-on gonzo-brilliant Village Voice critic, wrote explosively about dance on the Lower East Side (read Marmalade Me today!), but the lasting power of her work is in the way it takes us down a mind like a wormhole. I’ll also claim poet/writer Maggie Nelson for Team Critic: Her exquisite book The Art of Cruelty uses Artaud and Martin McDonagh to examine her own relationship to violence; she’s using theatrical concepts to sand her roughest thoughts smooth.

But while it’s delicious to read, inward-ism can be tricky—the art object itself recedes in significance, and a certain “It Happened To Me” laxness can creep into the work. But when it’s right? The prose can be world-changing.

The Proselytizer

The proselytizer is on a mission. Since making the case for hidden greatness is the critic’s most holy duty, stories about “finding” a great playwright are our most precious texts. In these moments, the critic’s black hat gets momentarily traded for the hero’s silver star. Think of Hermann von Ihering discovering Brecht! Or the way that Claudia Cassidy’s 1944 review of Tennessee Williams’s The Glass Menagerie (“If this is your play, as it is mine, it reaches out tentacles, first tentative, then gripping, and you are caught in its spell”) changed the course of history.

Proselytizers serve the art form more than they track the business. In times when U.S. drama ran thin, adversarial critics looked elsewhere, bringing word of great work from overseas. George Jean Nathan introduced America to O’Casey, Shaw, Strindberg, and Wilde; in the ’70s and ’80s, Richard Gilman, Robert Brustein, and Eric Bentley helped create our enduring appetite for Ibsen, Brecht, and Chekhov. In Commonweal and The New Republic and Commentary, they hammered together a new theatrical canon, one we’re watching still.

Proselytizers wield the greatest tool in the critic’s pack: attention. In theatre, attention is advocacy. When Frank Rich couldn’t sort out how he felt about Sunday in the Park With George, he returned to it again and again, keeping a difficult piece alive by the sheer dint of his steady interest. It was something only a New York Times critic of his era could do, but if we wish very hard, something like that time may come again.

And did you but know it—you’re surrounded by proselytizers. The Chicago Tribune’s Chris Jones is the kind of critic who calls up a journalist he doesn’t know in another town just to tell her about Ike Holter; in American Theatre Robert Avila brings back word from Russia and Hungary; at the Los Angeles Times Charles McNulty preaches passionate sermons for Annie Baker and Branden Jacobs-Jenkins. For myself, I would lie down in traffic for Sibyl Kempson. The calling is irresistible.

The Raisonneur/Raisonneuse

In the theatre, the raisonneur (one who argues or reasons) is the character who speaks soberly, sincerely, carefully. Staying a step outside the hurlyburly of the plot, he diagnoses and prescribes—in melodrama, he’s usually the doctor—looking on and articulating the philosophy of the play. The raisonneuse-as-critic is quieter than the other types; she plies her trade with the deliberate, rather than the flashing, pen. She tries to be clear, to be simple, to be trustworthy. She tries to get to the heart of the play.

A book of criticism, someone once said, is a book of witness, and it is vital that, in order that justice may be done, the witness be believable. Brooks Atkinson was the nonpareil of this type. Here he is on Eugene O’Neill: “What Mr. O’Neill has succeeded in doing in The Great God Brown…is obviously more important that what he has not succeeded in doing. He has not made himself clear. But he has placed within the reach of the stage finer shades of beauty, some delicate nuances of truth and more passionate qualities of emotion than we can discover in any other single modern play.” Look at the care in that sentence! And don’t be fooled—all that clarity is the stamp of passion.

Go also and read the reams of reviews by Mel Gussow, the keen mind who covered Off and Off-Off Broadway at the Times (and wrote the best biography of Edward Albee) for the proof. Gussow is such a delicate writer about that scene; you can tell he feels he’s handling robins’ eggs. Criticism isn’t just the rough draft of history. In our forgotten little corner of the arts, criticism is sometimes the only draft. So we desperately need writers with whom we can put our confidence—ah, yes, there was a show like this, and a play like that. That’s why I read Lily Janiak, David Barbour, Alexis Soloski, Elisabeth Vincentelli, and Lyn Gardner. In fact, I think people will be reading them 50 years hence.

The Scourge

In 1632, William Prynne published Histriomastix: the Player’s Scourge or, Actor’s Tragedy, which took the Puritan attitude that plays were ungodly, lewd, heathenish, the works. Not to worry: Prynne was pilloried and his ears were cut off because his attack was a reference to a court performance by the Queen. But some of our best (and still eared) critics are his great-grandchildren, marrying that clarity of moral rage to—and this would make Prynne crazy—a passion for theatre.

The scourges are the enforcers, the furious advocates, the critics who cannot afford to take any nonsense. They’re useful (read Rebecca West on “The Duty of Harsh Criticism”), and they’re so fun to read. Even now we can relish the icy sting of a mid-century Mary McCarthy take-down. Here she is, imaginary cigarette dangling from imaginary lip: “Indeed,” she drawls, “the American playwright is always being ‘excused,’ as though he were some wretched pupil bringing a note from his parent: ‘Please excuse Tennessee or Arthur or Clifford; he has a writing difficulty.’” (After transcribing that, I had to go lie down.)

Frank Rich, “Butcher of Broadway,” could slice to the bone. The dazzling Elizabeth Hardwick once came upon on “the evangelical urging of everyone to somehow take his own part in the theatrical event” like a divine hammer. In recent history, David Cote held the flaming sword: His Rabbit Hole pan in Time Out New York in 2006 is famous for its indictment of not only the play but also its theatre, its audience, and the entire society that birthed it.

Yet, though every critic still makes the occasional, furious denunciation, most negative reviews are now written more in sorrow than in anger. Why the change in tone? Habitat loss. First, the metrics tell us that a glowing review gets more clicks—of course it does, since it’s publicized and circulated by those who benefit from it. That pressure works quietly but pervasively, and though critics may not be consciously pulling their punches, the punches do get pulled.

It’s also the cost of losing something most people might not miss: pride. In the last 10 years, critics have been sliding into despair and disrepute simultaneously—the jobs are evaporating, interest in serious critical thought is waning, and yet no one seems too outraged about it. Much, much, much has been written (probably in this very issue) about the ways that critics need to abandon hidebound ideas, critical self-importance, old ways of thinking, elitism. And while I agree with much of these necessary critiques, we do lose something—even just vigor—when we drive the scourges out.

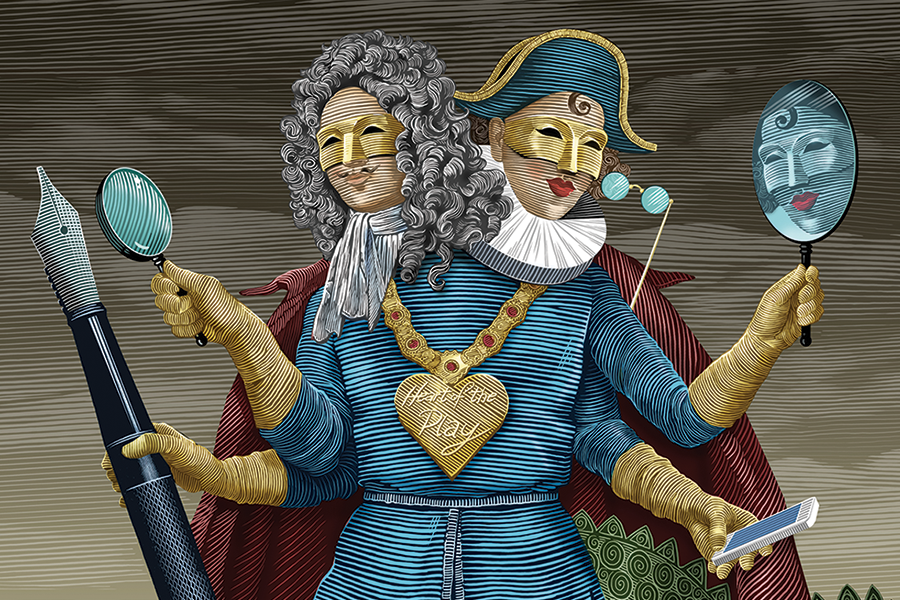

The Chimera

Writing this bestiary was meant to be my celebration of critics. I love the way my colleagues write—so many are artists in their own right—and the way they enter passionately into show after show after show. In fact, out of need, almost all of them function as a kind of hybrid beast: the multi-headed, jumblebox, facing every-which-way, just-put-a-tail-on-it chimera. They give themselves the legs of one thing and the head of another. They contextualize and proselytize in a single review; they try to be levelheaded raisonneurs and scourges at once. Everyone must do everything now, because there simply aren’t enough critics writing. Eden has dwindled into a roadside zoo.

But rather than celebrating, I’ve written myself into a terrible sadness. I feel like I’m writing an ode to the white rhino. There’s something mythological about some of these critical types now; others are dying right in front of our eyes. The answer, of course, is the answer to any kind of mass extinction. We focus on the habitat. We focus on breeding. And so we must immediately embark on an intense, frantic, wide-ranging publishing program. We must have more critics, more writing, more life.

Helen Shaw is a New York City-based critic and arts reporter.