I was an impressionable 12 years old when Shakespeare first stormed into my life. As I’ve reconstructed the dates, it all happened within a month in the fall of 1980. First up was a school field trip to the Scottsdale Center for the Arts, where Arizona’s Valley Shakespeare Theater had imported Jack O’Brien’s production of Romeo and Juliet from San Diego’s Old Globe. Tovah Feldshuh made a fetching Juliet, if my pubescent memory serves, and the dueling, dishing Mercutio of James R. Winker made a strong impression.

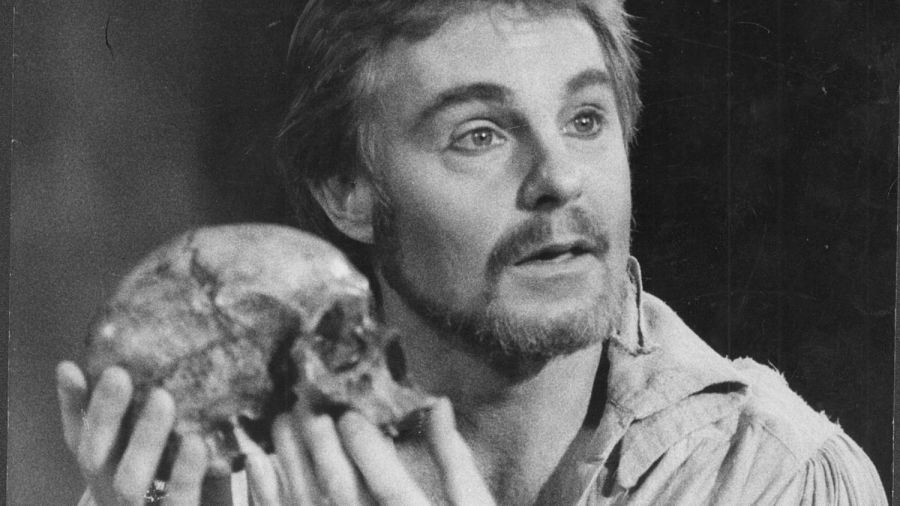

Less than a month later—roughly the week of Reagan’s election to the U.S. presidency, incidentally—PBS aired a BBC production of Hamlet, starring Derek Jacobi, Claire Bloom, and Patrick Stewart. I gobbled that up, cheesy soap opera-quality video and all. My family didn’t own a VCR then, so the only way to “replay” it was to nab a copy of the play from the public library. Though I’m still not sure why, I spent some idle hours over the next year memorizing the prince’s speeches and his cues, as if prepping for a production that had not yet been announced, let alone cast (my school had no drama program, and I harbored few acting ambitions). I must have had some inkling that this was The Role, and The Play, and the only way to get my mind around its enormity was to put myself in it.

I can’t claim that my apprehension of the Bard has expanded all that much from those strong early impressions on screen, stage, and page—though I must credit my first acquaintance with King Lear, in the 1984 PBS television event starring Laurence Olivier and Leo McKern, with the elementary tragic insight that repentance for wrong can’t reverse its consequences. (Hold the phone.) I’ve had countless high and low Shakespeare experiences since, from sketchy storefront theatres to the storied arenas of Ashland. But I’ll confess that apart from that early infatuation, I’ve largely taken Shakespeare the way our culture does: as a given, a brand name as much as a vital voice.

As an observer of the national theatre scene, this magazine does some similar taking-for-granted: Our annual Top 10 most-produced plays list, and the corollary Top 20 most-produced playwrights list, regularly excludes Shakespeare and his plays, along with the various Christmas Carols and Santaland Diaries (though we duly footnote the numbers for both the Bard and the holiday shows). The thinking is that including those perennial list toppers would push out other titles and names worthy of note. But a funny thing happened this year: Shakespeare made it to the helm of our Top 10 list, in a way, in the form of Lee Hall’s stage adaptation of the hit film Shakespeare in Love. And the Bard might be thanked in part for the high ranking of the most-produced playwright, Lauren Gunderson: Her play The Book of Will, one of several titles of hers slated for production in the coming season, riffs on the contentious assembling of the First Folio.

In early September I took my 8-year-old son to his first Shakespeare: the Public Theater’s heavily adapted, musicalized As You Like It, unfolding free of charge under a full moon in New York City’s Central Park. I’m not sure how well he tracked the show’s romantic peccadilloes, let alone cared about them, but I think it’s safe to call his reaction bemused. Asked for a highlight, he replied, of an early speech of Touchstone’s, “I liked the part where the clown dude was talking about mustard.” He hasn’t yet cracked our household copy of the play and started committing speeches to memory, but there’s still time.