The course of true fundraising never did run smooth. Just ask Randy Reyes, artistic director of Mu Performing Arts in St. Paul, Minn. In 2015, Mu applied for an arts access grant from the Minnesota State Arts Board to teach audiences about the history of Asian-American theatre. Though Mu’s mission and audience is Asian-American, they didn’t get the grant. “We were disappointed in that,” Reyes admitted.

But one organization that did get an arts access grant was St. Paul’s much bigger Ordway Center for the Performing Arts, which received $86,039 to present Notes From Asia, “a series of performances, films, conversations, and an exhibit that will highlight arts and culture of Eastern Asian communities for East Asian, Asian American, and broader audiences.”

Reyes felt this as a blow, since that description isn’t far off from the kind of programming Mu does. Why give the grant to a larger, non-culturally specific theatre? Said Reyes, “There are these assumptions that they can do this culturally specific programming because they’re the Ordway, and we somehow don’t have that capacity to work with a community that we have been working with for 25 years.”

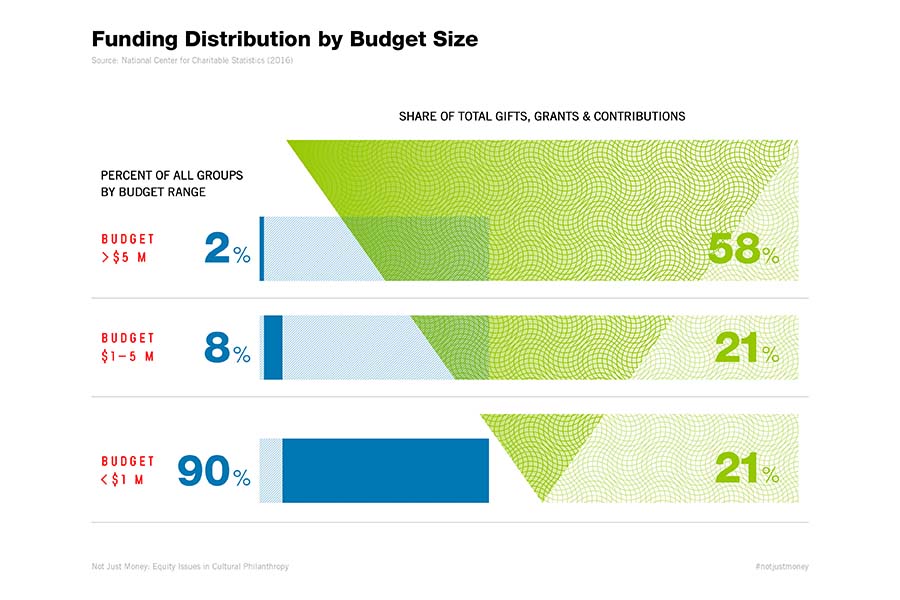

The likelihood that funders will shower money on large, mainstream organizations rather than smaller, culturally specific companies has just been borne out—again—by data. Last week Helicon Collaborative released a study titled “Not Just Money,” in which it analyzed funding trends across the country and found that out of 41,000 cultural groups (symphonies, opera companies, regional theatres, art museums, ballet companies, etc.), just 2 percent received 58 percent of all contributed income (measured as income from private foundations, public sources, and individuals). The 925 organizations in that 2 percent have annual budgets of more than $5 million, and focus on Western European arts and serve upper-income, predominantly white audiences.

More specifically, the study found that organizations focused on communities of color make up 25 percent of all arts nonprofits but receive just 4 percent of all foundation giving.

The study notes that these funding disparities are out of sync with a nation in which 37 percent of the population are people of color and 50 percent are low-income.

According to Helicon codirector Holly Sidford, these data are part of a longstanding trend that has shown no signs of changing—in fact, has gotten slightly worse since the last time Helicon released a similar study, in 2011, which found 2 percent of the arts institutions received 55 percent of funding.

“I don’t think any of the practitioners, that is people running arts organizations, were surprised by the data,” she said of that first study. “Everybody sort of knew what we wrote about experientially, but nobody had actually pulled the data together. Smaller organizations felt that they were disadvantaged and felt that the major institutions were getting the lion’s share of the money.”

But despite a growth in awareness among donors and theatres about the need for more equitable funding, the trend has actually worsened.

“I find it inexplicable, I really do,” exclaimed Brad Erickson, executive director of Theatre Bay Area (TBA), a service organization that disburses grants to artists in the San Francisco area, one of the few regions studied where funding equity has actually improved (more below). Erickson recalls sessions about the Helicon studies at numerous conferences for artists and funders. “Everyone in the room is nodding their head very gravely—it’s a terrible problem. I find it inexplicable that despite the fact that people in philanthropy knew about this, it continues to get worse and not better. I find that really surprising.”

For this latest iteration of the study, Helicon was able to break down the funding trends in 10 different cities and show that inequalities are magnified at the local level. For instance, in Minneapolis-St. Paul, Twin Cities institutions with budgets of more than $5 million make up 77 percent of all earned and contributed revenue, despite comprising only 5 percent of the arts ecosystem. When the numbers are broken down between mainstream arts organizations and culturally specific organizations: The former make up 83 percent of arts organizations and receive 90 percent of available foundation funding, while the latter make up 17 percent and receive 10 percent of foundation funding.

In this context it may be no surprise that the Ordway, a $15 million organization, is likelier to get a grant than Mu, whose budget is approximately $825,000.

Reyes further explained that in Minnesota a “legacy tax” of residents goes into public arts funding, and the primary distributors of funds are the Minnesota State Arts Board and the Regional Arts Council. “Everyone here pays taxes into this thing and it’s still not being distributed in a very equitable way!” he said. “It’s bias, it’s favoring large white organizations. You have to change the system in which this money is given away.”

That kind of change is exactly what “Not Just Money” recommends, and it’s a change that must be undertaken by both public and private funders. According to Sidford, after the first report “very, very few funders actually made a plan to change, and almost none made a plan to change in concert with other funders. That’s what we pulled people’s attention to in the new report. No one funder is going to be able to change the picture, and most nonprofit organizations get the bulk of their money from local sources. So it’s only by groups of foundations in a given place coming together and saying, ‘These numbers are unacceptable and we’re going to work together to change them,’ that real change can happen.”

San Francisco provides a hopeful example: It is the only city of the 10 studied in which funding is equitable. Culturally specific groups there make up 32 percent of all arts organizations—and approximately 32 percent of arts foundation funding is allocated to them. This is not an accident, Erickson said. It’s the result of advocacy in the ’90s by those groups. And local funders listened: Grants were created that only lower-budget theatres could apply for, such as the Cultural Equity grants from the San Francisco Arts Commission. Likewise, TBA receives funds from larger donors (such as the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation), which they then regrant to individual artists and smaller organizations.

“There’s a sense that the large-budget organizations had places to go to get money, but there was this greater need among small and midsize organizations, and among organizations of color that were culturally identified,” says Erickson, noting that theatres of color typically have much smaller budgets than their mainstream counterparts. “There was a concerted effort at the city government level and in private philanthropy to make sure that resources did go to small-budget and organizations of color.”

It’s a lesson for funders wondering how to make its gifts more equitable: Just do it, says Erickson. “It comes from intentionality; none of these come by accident. Just because you’re a person of goodwill does not mean that equity just follows in your path.”

And cities are becoming more intentional about it. Recently, New York City mayor Bill de Blasio announced the formation of CreateNYC, a diversity plan for the city’s cultural institutions. Among its many action steps, it will include a $1.5 million allocation for arts groups that work with low-income communities and “underrepresented groups,” and staff diversity will be a funding criteria.

A similar initiative is underway in Minneapolis. Reyes is part of a group called the Race and Equity Funding Collaborative, made up of theatres of colors and funders. “The big thing that we’re working on right now is what these funders and/or application processes, what their unconscious biases are,” Reyes explains. “It seems they skew toward numbers, and we’re trying to figure out how we bring up the value of our work and the longevity of the work in the community, and the depth of the engagement with these communities that we’ve been in.”

Larger arts organizations have a role to play in this as well, according to Sidford. First, they have to take responsibility. “A lot of donors take their leads from major cultural institutions about what is important and who are the artists to support and all of that,” she says. “So the larger cultural institutions have in my view a moral responsibility to not just look after their own individual institutional need but to think of the community as a whole.”

One way to do it, according to Reyes, is for larger organizations to partner more with smaller organizations, and share resources. “Think about real equitable partnership with theatres of color who are doing that work,” he urges. “You don’t have to reinvent the wheel.”