American Theatre asked two perceptive arts reporters—frequent contributor Mark Blankenship and former managing editor Stephanie Coen—to cast a wide net across the U.S. theatre landscape in search of artists, companies and projects that exemplify this issue’s Approaches to Theatre Training theme: social action and civic engagement. The resulting roundup of 14 mini-features illuminates a catalog of causes and a myriad of methodologies, tied together by the common thread of idealism and love of craft. These artists and companies utilize performance and performance training in the service of a larger good—and they’re by no means the only ones pursuing a change-the-world strategy on America’s stages, schools and streets.

—The Editors

Penumbra’s Sarah Bellamy Sets Her Sights on Social Justice

“Penumbra Theatre has always had a social-justice imperative at its core. But when it was founded in 1976, people couldn’t be quite as explicit in dealing with issues like racism as we can be today.”

That’s the St. Paul, Minn.–based theatre’s co-artistic director Sarah Bellamy speaking. A playwright, director and educator, Bellamy knows her theatre’s history well: She runs the pioneering African-American company alongside its founder—who is also her father—Lou Bellamy. “The social-justice issue is shifting to the front-and-center of our mission,” the younger Bellamy continues, “and we are trying to figure out how we can enact the principles of an activist theatre at all levels of our organization.”

One key way Penumbra is reactivating its mission is by rebuilding one of its flagship education programs, the Summer Institute, which is more than two decades old but was relaunched in 2006 under Sarah Bellamy’s leadership. Today the institute has an enviable 50 percent retention rate of students (ages 13–19) who remain for all three years of its programming. In the first year, students learn both craft-based theatre skills and about the concept of art for social justice; in the second year, they focus on one particular social-justice issue and write monologues about it; in the third year, in addition to advanced theatre studies, they take on paid internships and create their own original social-change art pieces designed to inspire and facilitate conversations around human-rights issues.

“We recruit students who are really diverse,” Bellamy notes. “Students that breathe theatre but never thought about social justice are working alongside kids who are active in debate and student council and community service, but never encountered theatre. What happens is that they start to co-teach each other inside the classroom environment—and they are fearless when they leave. It makes me feel better about the future of the world.” —S.C.

Luis Alfaro Focuses on Faith, Politics and Identity

Though he’s technically based in Los Angeles, where he teaches at the University of Southern California, playwright Luis Alfaro might just as easily be found at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival, where he is in the middle of a three-year appointment as the Andrew W. Mellon playwright in residence; in Chicago, where he’s an associate artist at Victory Gardens Theater; or in any one of hundreds of cities in crisis where, over the past 15 years, he has lived, worked, taught and embodied a philosophy that he calls “the Citizen Artist.”

“I try not to make a separation between how I live in the world as a citizen and how I live as an artist,” Alfaro asserts. “I come with an agenda: I am in the business of making art because I want to change the world.”

For Alfaro, this call to action comes from a central tenet: Every community has a story to tell. His job, as he sees it, is to “translate, challenge and interpret what the community needs.” In recent years, he’s done this, in part, by turning to the classics: His adaptations of Oedipus and Medea—titled Oedipus El Rey and Mojada, respectively—brought the epic qualities of Greek tragedy to a Los Angeles barrio and to the quiet life of an undocumented Mexican seamstress in Chicago. (Currently, Alfaro is working on a three-play cycle about faith, politics and identity in California, This Golden State, which will premiere as a coproduction between OSF and San Francisco’s Magic Theatre.)

And sometimes, he makes the work personal, as with St. Jude, an autobiographical solo performance that includes Alfaro’s rending account of taking care of his dying father. “I realized after the first few performances,” he says, “that I needed to take an hour-and-a-half after the show with the audience, hearing their stories, because a whole community was born out of people talking about their own sense of grief and loss.” —S.C.

SITI’s Conservatory Aspires To Be a “Thought Center”

In 2013—nearly 20 years into its history as “the most prolific unknown-known company in the country,” in the words of founding member and co-artistic director Ellen Lauren—the New York City–based SITI Company launched what Lauren calls “an act of faith in the generation upcoming behind us.” After two decades of touring, artistic residencies and creating new work nationally and around the world, SITI has expanded its work to include a biennial, year-round conservatory program that trains 20 international artists in the company’s core values.

Ellen Lauren (foreground), Akiko Aizawa, Katherine Crockett and Makela Spielman in “Trojan Women.” (Photo by Richard Termine)

Part of what makes SITI unique is the equal emphasis its members place on rigor and dedication to a series of very particular vocabularies—the SCOT Company’s Suzuki Method and the Viewpoints technique developed by Mary Overlie—and their dedication “to the value of passing along a way of being—model way to be together as human beings,” as Lauren puts it. “We decided that we weren’t going to try to generate SITI 2.0, but we wanted to pass along the value system that would allow people to make their own companies. It’s really about a way to engage with the world in a meaningful, objective way, so there’s language to have constructive conversations.”

In keeping with the company’s founding mission, SITI Company members who are not teaching will often be found alongside their students, taking classes taught by their colleagues. In addition to the Suzuki Method and Viewpoints, SITI’s training encompasses a range of other techniques, both traditional and contemporary (including the Alexander Technique, courses in dramaturgy and old-fashioned scene study) and master classes taught by company members and guest artists; the course culminates in a live public performance created by the graduates. As Lauren notes, “We never wanted to make a school—we wanted to make a thought center. The worst thing that can happen with performance art is that it’s vacuous.” —S.C

Stella Adler Studio Reaches Out to the Incarcerated

With its roots in the Group Theatre and Jacob Adler’s political activism, the Stella Adler Studio of Acting has been synonymous with social engagement since it was founded in the 1940s. Still, the company’s outreach division isn’t content to rest on a legacy. That’s why, last year, it launched a new project with inmates at Rikers Island, the notorious prison complex in New York City.

“Jails and prisons seem to be places where humanity is under siege,” says Tom Oppenheim, the Studio’s artistic director. “Particularly in this age of mass incarceration, it seems like the right place to bring the opportunity of theatre to uplift and rehumanize.”

Through a series of acting classes and theatre workshops, inmates create and perform original material about any issue they choose. Currently, the program serves both young men in the Rikers Island high school and women from the all-female facility, and Studio reps hope to reach the adult male population soon.

Initial feedback has been undeniably inspiring. Describing a female prisoner at a post-performance Q&A, Oppenheim recalls, “She said, ‘I found I was able to communicate in here’—meaning at Rikers—‘in ways that I’ve never been able to out there.’ “For me,” Oppenheim observes, “that’s a reminder that theatre has the capacity to heal, redeem and rehabilitate.”

However, this program doesn’t only enrich the prisoners. Last December, students in the Studio’s joint B.F.A. program with New York University were in the audience for a performance by the female inmates. The event underscored how the very art they were studying could affect someone’s life.

That idea is also embedded in the studio’s mission, which says, “Growth as an actor and growth as a human being are synonymous.” As Oppenheim puts it, “The mission focuses on the power of theatre to activate students as citizens and engaged human beings. It’s not their only priority, but it’s certainly more important than fame and fortune.” —M.B.

Double Edge Training Is an Amalgam of Sustainability and Change

“It’s organic for an ensemble to grow generationally,” says Stacy Klein, co-founder and longtime artistic director of Double Edge Theatre Company, the physical-theatre ensemble and touring company that has made its home since 1994 on The Farm, a self-sufficient 105-acre artists’ haven in Ashfield, Mass.

Klein is referring to the recent announcement of the company’s first artistic leadership shift since it was founded in 1982—she is being joined at the helm by her husband, lead actor Carlos Uriona, and Matthew Glassman, a younger artist who was trained by Klein and Uriona. Glassman calls them his most important teachers.

What will not change is the company’s agenda: creating and touring its visually rich immersive theatre pieces and offering year-round training programs on The Farm.

For all three artistic leaders, that double commitment represents the most important thing about Double Edge: its conviction that artists are both autonomous and deeply connected to their communities. “We moved to The Farm from Boston, choosing to make our roots in a rural place,” Klein notes of the company’s evolving mission. “And we began to think about our training programs, which have always focused on the agency of the actor. We realized that a community’s ability to be sustainable and the artist’s ability to activate social change are not on different tracks.”

Today, that sense of connection informs all Double Edge’s work and its extensive training programs. At the end of this month, the company will embark on its spring immersion, a collaborative three-month program that will provide opportunities for students to work with a cluster of five different theatres around the country, all founded within the past 20 years, and all of which have members who trained with Double Edge. As Klein notes, “This gives our students the opportunity to go to a place like Albuquerque, N.M.”—where they will spend two weeks with the q-Staff Theatre—“and discover how you can create a space, and train together, and make an impact on whatever community you are working in.” —S.C.

Catherine Filloux’s Selma ’65 Confronts Voting Rights Rollbacks

Catherine Filloux didn’t just write a play about the violence of the Khmer Rouge. She took it to Cambodia, where it was performed in Khmer for local audiences. In December 2013, she likewise took her play on honor killings to northern Iraq, in the region now occupied by ISIS.

It makes sense, then, that Filloux’s latest activist-minded drama will tour the United States this year, asking Americans to confront a problem that threatens to poison our democracy all over again. In the wake of the Supreme Court’s 2013 invalidation of part of the Voting Rights Act, she’s written Selma ’65, which resurrects the legacy of Viola Luzzio, a largely forgotten civil rights activist who was murdered by the Ku Klux Klan shortly after the Selma voting march.

After premiering at La MaMa ETC in New York City last fall, the play will visit college campuses and justice centers from Washington, D.C., to Ypsilanti, Mich. And based on response to the New York production, it may leave audiences unsettled. “I got a lot of feedback that people were haunted by the story, and it made them want to know more,” Filloux says. “People don’t necessarily know how bloody the struggle was for voting rights.”

Even as she’s resurrecting old tragedies, however, Filloux won’t tell us how to feel about them. She says, “I don’t write ‘message-oriented’ plays. I tell stories, and they can be interpreted in many different ways. I think that provides some opportunities for creative thinking and empathizing that are different from what you get in a history book.”

Filloux, who’s currently on the playwriting faculty at Vassar College, adds that the space for interpretation is what makes theatre such a valuable tool: “I want to be able to use my theatre work to create a dialogue, and a play can stand outside of politics and be self-contained in a way that lets people talk about the issues without having to feel that they are necessarily taking a political stance.” —M.B.

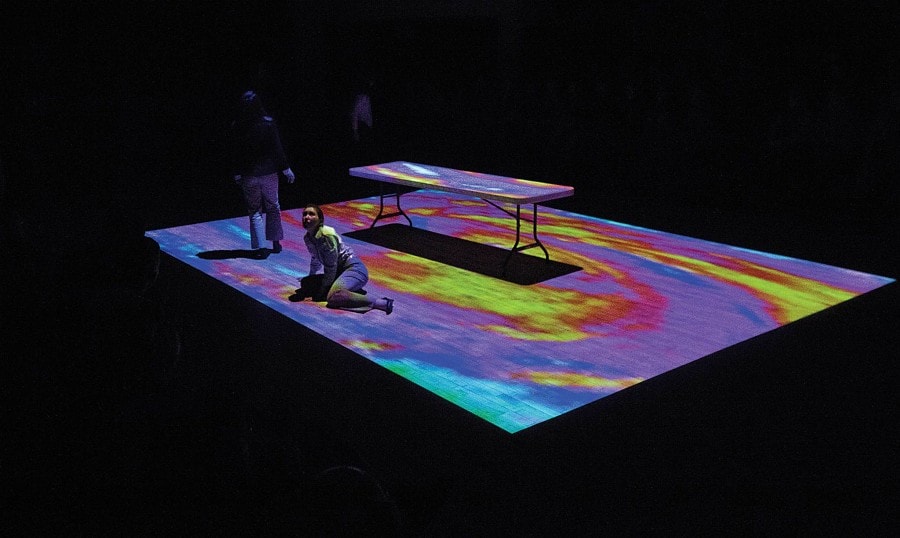

Dawn DeDeaux’s MotherShip Prepares for Planetary Evacuation

Conceptual artist Dawn DeDeaux has a full-throated laugh and a wry sense of herself as someone who is “working the cracks,” as she puts it—a phrase that refers to the intersection of visual arts and what she identifies as “electronically driven” theatre. In that meeting place, she makes works that have serious narratives, but are realized as site-specific installations without live actors. Her large-scale, mixed-media MotherShip trilogy—a response to astrophysicist Stephen Hawking’s assertion that humanity has 100 years left not to save the Earth but to leave it—is an immersive, “future-tense” installation of sculpture, drawings and digital technology inspired by ancient myths, mathematical forecasts, symbols, visions of apocalyptic landscapes and utopian longings.

The series—presented in New Orleans at two sites through Jan. 25, as part of the city’s Prospect 3 Biennial visual arts festival—is rooted in place: specifically, DeDeaux’s native Louisiana, where the ravages of Hurricane Katrina and the BP oil spill became a wake-up call for social activism. Developed in part during her residency at the environmentally focused artists’ retreat A Studio in the Woods, just south of New Orleans, DeDeaux’s installations are, in effect, tools for training a mass audience to think about the possibility of exile—and become part of the solution to global environmental problems.

One of DeDeaux’s earliest inspirations, she notes, was Marshall McLuhan’s theory of the global village. “All of a sudden a light bulb went on—there is a world getting ready to change because of mass communications. How many people can I impact with one painting? Today, I try to find ways to engage the public on a visceral, emotional level, without being dogmatic or sensationalizing pain and fear,” she says.

One of the components of MotherShip III is Souvenirs of Earth—a collection of items left by the public in response to the question, “If you could take only one thing with you when you leave Earth, what would it be?” Answers so far have ranged from pet hair to photographs, from lots of seeds and bits of soil to a nearly disintegrated baseball bat and a pigskin football—what DeDeaux calls “anchors to real Americana. There’s something so poignant about an old wooden baseball bat.” —S.C.

From Norma Bowles and Fringe Benefits,100-Plus Plays with a Message

Racism. Sexism. Classism. Able-ism. “Looks”-ism. Homophobia. Transphobia.

These are just some of the issues that have been tackled by Fringe Benefits, the activist theatre company that generates plays and performance events in collaboration with school and community groups. Founded in 1991 in Los Angeles by its ongoing artistic director Norma Bowles, Fringe Benefits pushes for constructive dialogue about diversity and discrimination issues via such productions as Cootie Shots and 90210 Goes Queer! Southern Illinois University Press recently released a scholarly anthology of essays about its methodology and collaborations, Staging Social Justice: Collaborating to Create Activist Theatre, coedited by Bowles and Daniel-Raymond Nadon.

“The plays we’ve helped devise have helped to end classist school policies, garner votes for marriage equality, secure funding for housing homeless youth, launch a staffing service for formerly incarcerated women, and inspire and equip youth with strategies for stopping bullying,” recounts Bowles, a tireless campaigner for the efficacy of theatrical activism who has been widely honored by such pillars of the establishment as the Association for Theatre in Higher Education. The more than 100 original works in the company’s repertoire have been developed through acting, commedia dell’arte and new-play-development residencies—forms that Bowles finds especially effective for her purposes.

“Often as theatre activists, we are hoping to reach and move audiences who disagree with—or at least have not previously shown an interest in supporting—the causes we are championing,” she notes with a qualifying gesture. “So, to develop plays that seek to promote social justice, we need all the creative artistry and skill that we would need to create ‘art for art’s sake’—and more!”

Most recently, Bowles has expanded the company’s purview to include education, mentorship and training on a university level, and she is currently leading a two-year Fools4Change! residency at Loyola Marymount University. “We’re introducing students to diverse methodologies for creating theatre for social justice, and helping them grapple with the myriad ethical, legal, aesthetic and practical issues involved,” she explains, “so they can develop their own unique and thoughtful approaches to doing this important work.” —S.C.

Sister Sylvester Updates Genet’s The Maids by Casting Real-Life Domestics

The title, in some sense, says it all. In Sister Sylvester’s The Maids’ The Maids, Jean Genet’s 1947 drama is performed by, well, actual domestic household workers—turning Genet’s hothouse of a play about class, power, fantasy and murder into a meditation on “the intersecting fault lines of labor, language and power” in New York City today.

The subversive, ensemble-based company Sister Sylvester was formed to do another Genet play, The Screens. “Genet has always fascinated me, because he interrogates power dynamics within our society—the games that we play every day—in a really complex way, without providing an answer,” director and company founder Kathryn Hamilton explains. With The Maids’ The Maids, she set out to explore the intersection of art and social activism by casting both professional actors and nonprofessionals—real-life housekeepers who perform in their native languages of English, Spanish and Portuguese.

“Audiences that speak Spanish or Portuguese have a slightly different understanding of the piece,” Hamilton allows, “but moments of incomprehension are ways to invite audiences into it. Audiences become participants within the piece—but without it being a conscious conversation. A lot of the way we work as a company is through direct address, through the audience, and that changes the dynamic between the actors onstage.”

Developed via a three-week workshop and then a four-week rehearsal process, The Maids’ The Maids remains a work-in-progress, Hamilton says. She was initially worried about power dynamics that might have been inherent in the making of the piece—the potential imbalance between actors and laborers—but her fears proved unfounded. “In the process of making it, I thought there would be a divide between the professionals and the nonprofessionals in their respective roles in creating the piece. But about halfway through rehearsals, everyone became ‘professional’ actors, having the same kind of responsibilities. I also didn’t know how the nonprofessionals would respond to being in front of an audience, but in the end, they loved it.” —S.C.

Plan-B of Salt Lake City Acts Locally and Adorably

If you’re a theatre dedicated to local issues, then Utah’s a pretty good place to call home.

Just ask Jerry Rapier, producing director of Plan-B Theatre Company in Salt Lake City. Noting that SLC is a liberal place in a red state, he says, “People have a very specific idea of what our city is like because of what our state is like, so there’s immense fodder for exploration there.” Plus, he adds, “Our mission is in some ways rooted in the relationship between the gay community and the Mormon church.”

And since Plan-B is focused on producing new work by Utah-based playwrights, the company can address these issues head-on. This season, for instance, it has already presented shows like Pilot Program, a comedy about a plan to restore polygamy, and Marry Christmas, which looks at gay marriage’s recent arrival in the Beehive State.

But the company doesn’t always need hot-button topics to engage its audiences with serious issues. Sometimes it just needs adorable dogs. This fall, Plan B will tour local elementary schools with Ruff!, a play for young children that uses the adventures of two shelter dogs to teach lessons about bullying and acceptance. (This is the company’s third year touring schools, which helps offset the shrinking arts spending for Utah’s students.)

As cute as Ruff! sounds, though, it’s the end of the show that makes it a must-see. When the play is over, children get to spend time with trained therapy dogs—a perk that really ought to be part of every production in America.

But these animals do more than get their ears scratched. They also reinforce the message of the play, particularly for children who might be timid around animals. “If the play helps kids understand how dogs think and react a little differently, then that’s a huge success for us,” Rapier says. “If they take a step forward and are able to use that in their interactions with other kids, that’s even better.” —M.B.

Andrew Hinderaker’s Colossal Tackles Football and Disability Issues

“What does it say about me that I love this game so much—a game that destroys a lot of people who play it and lifts up a troubling idea of what it means to be a man?”

That question drove Andrew Hinderaker to write Colossal, a play about the ecstasy and brutality of American football. In many ways, the show’s a rush, evoking gridiron intensity with everything from modern dance to a live drumline. But underneath that style there’s a serious story about a gay player who ends up in a wheelchair after suffering a devastating spinal cord injury on the field.

Hinderaker, a lifelong football fan, began the script when he was a graduate playwriting student at the University of Texas. “Our theatre building was literally in the shadow of this 105,000-person football stadium,” he says, and he wanted to probe his own ambivalence about the game.

As it’s amassed productions, however, it’s become clear that Colossal is not only a critique of pigskin culture, but also a flashpoint for the American theatre’s relationship to actors with disabilities. That’s because Hinderaker insists that Mike, the character with the spinal injury, always be played by an actor with a disability.

This codicil wasn’t initially part of the plan. Hinderaker built the play around his friend and collaborator Michael Patrick Thornton, who happens to be in a wheelchair, so at first there was no question about who would play Mike.

But now Colossal is in the midst of its rolling world premiere via the National New Play Network, with productions at Dallas Theater Center, Company One in Boston and New Orleans’s Southern Rep coming this year after last fall’s stagings at Maryland’s Olney Theatre and Mixed Blood Theatre of Minneapolis. Thornton can’t be in all those places, and Hinderaker realized he couldn’t support a non-disabled actor in the role.

His decision is partly based on conversations he’s had with advocates who bristle when an actor without a disability plays a character in a wheelchair. “It’s just listening to a group of people who aren’t often listened to,” he says. “It’s just listening and trying to do it right.” —M.B.

Eleanor Bishop Steers Steubenville to Address Campus Rape

Among the many horrors of the 2012 Steubenville, Ohio, rape case was the fact that much of the assault on a drunken high school girl was documented on social media. The lurid glee with which certain members of the community spread the news among their networks underscored that this particular crime was grotesquely au courant. It was possibly the first rape to be tweeted.

That, of course, gives the case a particular resonance with young people, which is why Eleanor Bishop is tackling its legacy with a group of undergraduates at Carnegie Mellon University. A directing student in CMU’s school of drama, she’s working with them to create Steubenville, a documentary theatre piece that combines trial transcripts and social media from the crime with the artists’ own observations about being young women in America.

Discussing the show, which will premiere this March, Bishop says, “I’m very excited that it’s being made on a college campus, given that sexual assault on college campuses is such an important issue at the moment. These young people, the actors, are 20, and they’re hungry to make work about their sexuality and how they navigate their sexual relationships.”

This is not the first time Bishop, 28, has used devised theatre to address a social problem. Before enrolling at CMU, she created a piece in her native New Zealand that confronted the country’s binge-drinking epidemic among students. (That show, Like There’s No Tomorrow, will tour New Zealand this year.)

In both cases, creating the play with her ensemble has made it even clearer how potent the issues are. During a rehearsal for Steubenville, Bishop ran an exercise in which the performers stood in a particular place based on how “slutty” they thought they were. “That generated half an hour of heated discussion,” she says. “It was confusing and baffling and infuriating for them, and as a director you go, ‘There’s something here. I want to harness that energy.’” —M.B.

Cleveland Public Theatre Makes a Case for Clean Water

Cleveland Public Theatre has a long history of mounting social-justice work,

addressing everything from the lives of the local homeless population to the experience of young people in public housing. But when it came to environmental issues, artistic director Raymond Bobgan always passed.

“I had stayed away from the environment because I couldn’t find a way in,” he says. “Either you end up with a play that says, ‘Come on everybody! Recycle!’, or you end up with a play that’s like, ‘The world is going to fall apart, and we should all just give up.’”

Bobgan got a little greener, though, when CPT developed a partnership with Oberlin College and the conversation turned to water usage and sustainability in the area. The connection to local lives made the concept of eco-theatre seem both manageable and appealing, and in 2013 the company launched the Elements Cycle, a four-part series dealing with everything from mining to air rights.

In February, the cycle concludes with Fire on the Water, an evening of interconnected short plays inspired by the besmirched history of the Cuyahoga River, which was so polluted that it burned at least 13 times between 1868 and 1969.

To stress the contemporary relevance of those historical fires, CPT is partnering with several government institutions, including the regional sewer district and the local department of sustainability, to ally the show with other events in the city’s “Year of Clean Water” program. Crucially, too, the short plays, which range from movement-based works to interpretations of historical documents, have been created by a collection of local theatre companies.

These partnerships illustrate the communal quality of the work, which Bobgan hopes will lead to direct action in Cleveland. “Our goal isn’t that everyone recycles after seeing this play,” he allows. “We’re saying that the role art can play is to shift consciousness—so that later, when people learn about specific things they might do, they might actually want to do those things because they’re thinking about them differently.” —M.B.

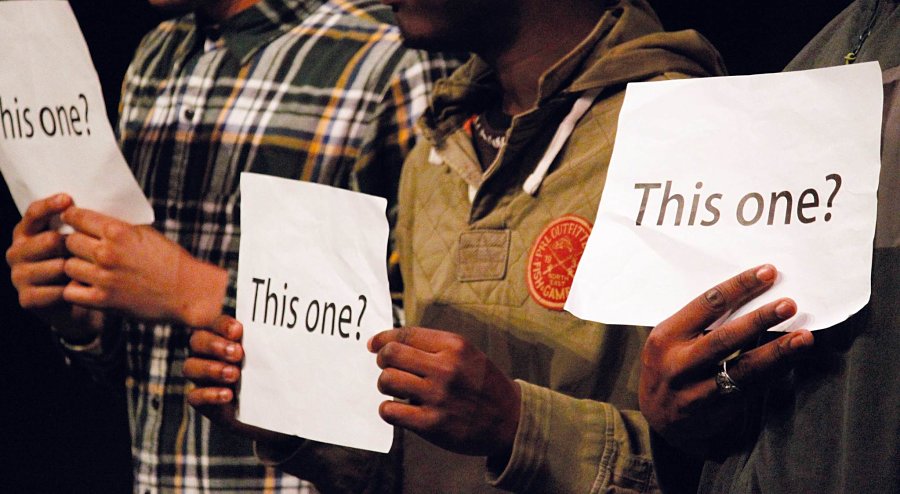

Theatre of the Oppressed NYC Corners City Politicians

There’s political theatre, and then there’s theatre that actually performs in a house of politics.

This year Theatre of the Oppressed NYC plans to take an activist-minded show directly to a New York City Council meeting, hoping it will sway votes in favor of a bill that requires police officers to both identify themselves before a search and gain consent to search in the first place.

NYC’s “CASES.” (Photo by Aliyah Hakim)

The show will likely have an impact. After all, since forming in 2011, TONYC has developed strong relationships with local politicians, and every year it invites them to the Legislative Theatre Festival, where citizens perform work about significant local issues. Taking a show directly to chambers is the logical next step.

As their name suggests, the troupe follows the model of Augusto Boal, the late director-activist whose book Theatre of the Oppressed is a touchstone of socially conscious drama. TONYC uses Boal’s tactics to give at-risk communities a chance to respond to their problems with original art. Their 10 current troupes include people with HIV and AIDS who have experienced homelessness; LGBTQ homeless youth; and students at LaGuardia Community College who are exploring gender identity and Islam.

“They’re the actors, the playwrights, the directors, the designers, the producers,” says TONYC executive director Katy Rubin, who notes that company members facilitate each group’s work without creating or controlling it. “They are dictating the form of the artistic representation.”

Each play presents questions about social dilemmas—like, say, the struggle for affordable housing—without providing answers. Instead, performances end with audience members jumping onstage and enacting their own ideas for how to solve the problems in front of them. As Rubin notes, “The actors are saying, ‘This is what’s happening to us, but we don’t know any better than you right now how to fix it.’ That’s why it’s an urgent question.”

That element of participation may prove especially powerful when TONYC visits the city council, where the show will be performed by a group of recently incarcerated youth. Once legislators are forced to step inside the experiences of their constituents, they may be compelled to listen, empathize and change. —M.B.