PROSPER:

My parents had settled down in California,

Their final stop on mankind’s constant search

For fuller stomachs, laughing days, warm sun.

With work and welcome, they grabbed fast the dream.

And California grabbed right back, so I

Got education, friends, a shining future,

And that most perfect gift—the firm belief

That human beings, with combining effort,

Can make their lives, all lives, at least some better.

The speech comes early in California: The Tempest, Cornerstone Theater Company’s groundbreaking statewide touring show. It offers both a sample of cofounder Alison Carey’s inspired, state-specific adaptation of Shakespeare’s final full-length play, and a crystallization of what America’s premier community-engaging ensemble strives for—and, with this ambitious project, is literally in the process of realizing.

The tour caps a 10-year experiment with 10 communities across the Golden State, places that have been the sites of Cornerstone’s Institute Summer Residencies. In the program, which has sought to impart Cornerstone’s unique methodology to new generations of theatremakers, company members and students visit a locale, get to know the residents and terrain, then conduct an intensive month-long program that models the Cornerstone approach by creating an original production for and with the community.

Paula Donnelly, who began with Cornerstone as a stage manager and has been director of the institute since 2003, recalled that the first residency was in the summer of 2004; 18 students “lived, studied, rehearsed and performed” at Lost Hills School, about 40 miles from Bakersfield in central California.

Cornerstone has been around for nearly three decades, but the notion of teaching others what the company does only began incubating within Cornerstone’s consensus-based ensemble around the turn of the millennium. In 2001, the company created a community-based play and taught some of its techniques via California State University–Fresno’s summer arts program, which formed the prototype for the institute summer residencies.

Donnelly says the thinking behind the institute harks back to the company’s origins as an itinerant company roving across America creating plays—a chapter that essentially came to a close when Cornerstone put down roots in Los Angeles in 1992, and then embarked on community projects organized around different regions and themes embodied in Southern California’s diverse sprawl.

“The company was interested in reconnecting with the immersive experiences of our early ‘rural’ years,” Donnelly explains. Picking collaborators within the city of Los Angeles had been one thing, but “the idea of specifically living as outsiders in and among the collaborating community is uniquely informative. There was an idea to create a new touring ensemble that would use college or graduate students to do residencies in small or rural communities.

“The summer residency is obviously a bit more compact than Cornerstone’s typical process,” she adds, “but it’s also geared toward an idea, or theme, and the exploration of a particular community—building relationships between the artists and the people there.”

The result: shows that reflect the towns, areas and communities where they’re happening, and stimulate a dialogue around the subjects being explored in performance.

The new Tempest meets that goal in spades. Over the past decade, the institute has put down stakes in a welter of California towns—Arvin and nearby Lamont and Weedpatch; Lost Hills; Grayson and Westley; Pacoima; Fowler; East Salinas; Holtville; Eureka; San Francisco; and the Downtown Los Angeles Arts District. Now, in a dizzying, daunting enterprise, members of these disparate communities are coming together in a three-pronged, yearlong tour of a specifically rethought take on the Bard’s magical tale of treachery, forgiveness and redemption.

The new Tempest meets that goal in spades. Over the past decade, the institute has put down stakes in a welter of California towns—Arvin and nearby Lamont and Weedpatch; Lost Hills; Grayson and Westley; Pacoima; Fowler; East Salinas; Holtville; Eureka; San Francisco; and the Downtown Los Angeles Arts District. Now, in a dizzying, daunting enterprise, members of these disparate communities are coming together in a three-pronged, yearlong tour of a specifically rethought take on the Bard’s magical tale of treachery, forgiveness and redemption.

Not only does The Tempest pull together Cornerstone ensemble members and institute participants; the structure of Carey’s script—in which Shakespeare’s Prospero becomes Prosper, a former governor of California usurped by her sister Antonia (not Antonio, in another of the text’s adroit gender switches)—calls for four individuals from each community to appear onstage when the play is performed there, chiming in at the show’s celebratory climax to share what’s unique about their homes.

In terms of logistics alone, it is probably Cornerstone’s most ambitious project in decades, if not ever.

“It’s absolutely a massive undertaking,” confirms artistic director Michael John Garcés, who has been with Cornerstone since 2006 and who directs the touring Tempest. After doing the residencies in each community over the past decade, he says, “the conversations that emerged in each area kept running along similar lines. And what started out as sort of an in-house joke was, ‘We should figure out a way to bridge these towns.’”

The joke soon became a plan, and the B-word became flesh, in a sense—“bridge” shows, undertaken periodically as thematic summations of a series of smaller residencies, are a Cornerstone trademark.

Eyeing the California landscape, Garcés says his “first impulse was to talk to Alison, because she’s so experienced in the work.” Carey, a founding member of the troupe, left for a job at Oregon Shakespeare Festival in 2007. Bringing her back for another bridge show “felt like a nice full-circle moment,” says Garcés.

Carey concurs. “It is full circle, in terms of my cofounding the company, and also in doing a Shakespeare adaptation geared to a specific location.” A bit of history helps to complete the pictures. Carey and director Bill Rauch began Cornerstone in 1986, forming a traveling troupe with other artists they had met while at Harvard. Their goal was to bring versions of the classics that incorporated aspects of the rural and urban communities they visited.

During the first five years of the company’s existence, Cornerstone presented adaptations of Shakespeare, Coward, Ibsen, Molière, Aeschylus, Brecht, Auden, Isherwood and an original show, all refitted to the particulars and individuals that the company met in such far-flung destinations as North Dakota, Texas, Oregon, Kansas, Florida, Mississippi, Nevada, Maine, several Virginia locations and West Virginia.

Those initial excursions—with company members taking up temporary residence in the selected cities and towns, getting to know the locals and their histories prior to concocting the scripts and productions—merged in a 1991 bridge show. Created to bring together all 12 communities with a 10,000-mile national tour of The Winter’s Tale: An Interstate Adventure (in which the company tour bus also served as a major piece of the set), the bridge show was a success on all fronts—and became a company signature.

Bridge shows also capped the so-called cycle plays, a series that emerged after Cornerstone settled in Los Angeles and began focusing on urban collaborations. Taking a multiyear approach to multiple communities focusing on a singular topic, the Watts Cycle (race relations between African-American and Latino communities in Watts), the Faith-Based Cycle (groups and communities of faith in Los Angeles) and the Justice Cycle (how laws can better or upend lives) have made the kind of impact, both socially and artistically, that many a repertory company can only dream about. With these efforts, Cornerstone has become the gold standard for a now-established brand of socially engaged, community-embedded theatre.

Cornerstone isn’t the only company of its kind—a similar ethos animates Sojourn Theatre of Portland, Ore., Ten Thousand Things Theater in Minneapolis and the Public Works program in New York City—but in founding an institute, Cornerstone has announced and acknowledged its status as a national leader of this type of work. Over the 10 years they’ve been doing the institute, Donnelly tallied 162 graduates, ranging in age from 18 to 64, from 25 states as well as Mexico, Romania, Singapore, the UK, Japan and Turkey. She describs them as “theatre artists, community-center directors, musicians, composers, educators, students, writers, wanderers, health workers, filmmakers and one Jesuit priest”—a Cornerstone community in itself.

Which brings us to the present day: California: The Tempest is united not only by locale but by a thematic cycle of plays called the Hunger Cycle, of which this bridge tour is a penultimate part. For the past six years (including the preparatory investigative residencies), Cornerstone has explored the topic of hunger, food equity and justice through world-premiere plays, often built on classics: Lunch Lady Courage, for example, reimagined Brecht’s Mother Courage as a high school food-cart lady. Meanwhile, ongoing Creative Seeds events brought artists, activists, community leaders and others together to share their experiences with hunger.

Considering that Cornerstone operates on a pay-what-you-can admission standard—and that the Tempest tour is, even with grants and donations, heavily reliant upon barter, volunteer services, creative housing arrangements and other elements that hearken back to the traveling players of old—the motifs and specifics of Carey’s script and Garcés’s direction dovetail neatly into the themes of this particular cycle.

This was evident as early as last August, when the show’s first public performance took place at California Plaza in downtown L.A. It was done as a staged reading with an expansive cast that included Cornerstone ensemble members and various cycle and bridge participants who represented the 10 communities. Even then, at a first post-larval stage, with the actors using chairs and music stands across an open-air amphitheatre, the potential scope and sheer imagination afoot was apparent. Turning the storm-tossed ship of the play’s opening into a turbulence-ridden plane and making the tempest at sea a tsunami and earthquake that leaves California destroyed—all manipulated by Prosper from her mountaintop sanctuary, Ariel from aboard the plane—the piece instantly grabbed the postmillennial audience where they live.

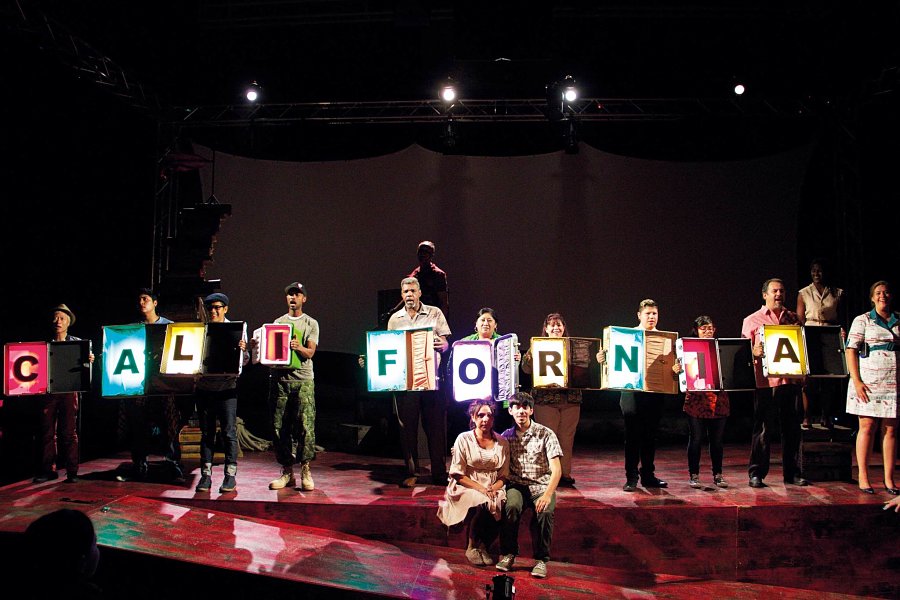

in “The Tempest.” (Photo by Kevin Michael Campbell)

In performance, the gender-switching worked beautifully to illuminate the essence of Shakespeare’s narrative, in tandem with the true ethnic diversity of the company; not only were Prospero and Antonio turned into women, they were African-American women, to boot.

“It came first from my wanting Prospero to be a woman,” Carey notes, “and then to be a person of color, which was exciting to me. I think the postcolonial interpretation of the play is what it is, and it’s something of a trap, and it’s been done. And that’s not what we wanted to say. The pain of the white man is a beautiful and true thing dramatically, but that’s not what Cornerstone needs to put front and center in this play.”

That also applies to the text’s handling of Caliban, so often portrayed as the monster Shakespeare describes. Here he’s very much a multifaceted creature of the Earth, and more. “He is an incarcerated individual in the state of California,” notes Peter Howard, whose longstanding Cornerstone participation has including writing and directing shows for the troupe. The role, Howard adds, is really about “what it means to be perceived as monstrous, through the specific lens of this state. For instance, here in our times of drought, what beverage commands Caliban’s focus? Not alcohol. Water.”

At the Grand Avenue preview, the mix of professional and nonprofessional performers, always one of the most invigorating aspects of Cornerstone’s ethos, was more than promising—it was wildly impressive. Cornerstone member Bahni Turpin conveyed resonant authority and no small measure of wit as Prosper, suggesting a character somewhere between C.C.H. Pounder and Wanda Sykes’s more sober cousin. Conversely, institute alumni Karen Covarrubias as Minerva (the name change from Miranda is a deliberate nod to the Golden State, for a reason delightfully revealed at the denouement) and Brent Grihalva as Ferdinand had a spontaneous charm that far outweighed any lightness of technique or projection.

And so went the roster, whether it was E’Vet Thompson making imperious mincemeat of Antonia’s pre-crash assertion, “Not God or Mother Nature pulls us down. But rank incompetence. The only comfort I have in death is their deaths next to mine”; or the calmly antic, steadily sparkly Ariel of Chelsea Gregory (who goes in for Cornerstone mainstay Page Leong in Grayson, Pacoima, Fowler and East Salinas); or founding member Howard, a restive, raging Caliban, clearly not only a stand-in for the incarcerated but for the environmentally aware, as well. His “monster” had a grandiose fervor that brought the role’s humor and consciousness-raising pathos into vivid bas-relief.

That said, the text was longer than practical for touring, the first half clocking in at well over an hour and 45 minutes. And for all the cheeky humor and iambic inspiration of Carey’s analogies and wordplay—a number of passages seemed list-heavy with references to the key attributes, usually culinary, of the 10 communities incorporated, which prohibited the flow of a story already zigzagging in its original form—clearly there was further work to be done. As Garcés puts it, “The whole tour is an out-of-town tryout.”

This, along with the concept’s innate excellence, was confirmed two weeks later in Arvin, where the tour made its first stop at the Sunset School in Weedpatch. Walking into a converted school gymnasium, through a lobby with a “Local Treasures Map” and bilingual charts relating “El Futuro” of Arvin and Californa, my immediate reaction was one of tingling excitement, which the chattering locals and scampering children milling about only heightened. Upon first view of Nephalie Andonyadis’s set, a lightpole-framed wonder of red mottled platforms, the room was ready to rock.

While waves of ocean noises flooded Veronica Vorel’s soundtrack, Turpin as Prosper, barefoot and dressed by costumer Garry Lennon as something between a shaman and a beatnik, did t’ai chi–like moves, even during Garcés’s bilingual preshow announcement. And from the opening sequence—in which a flying plane puppet interfaced with Leong’s mercurial, blue-haired Ariel while the airplane passengers, complete with seat cushions attached to their wardrobe, banked on either side of the space—spectators were clearly in for something special.

So it proved, even if the script still needed cuts and then some, with Geoff Korf’s superb, Bauhaus-meets-Baja lighting, Lynn Jeffries’s adorable puppets and Becky Dale’s original music all invaluable in bolstering the atmospherics. Leong was particularly on form, her liquid gestures and hairpin turns of expression enlivening even the most run-on sequences; Howard made Caliban a figure to be pitied and feared even more evidently than before. Indeed, the ensemble as a whole ranked among Cornerstone’s most effective assemblages of company and local talent to date.

The staging featured many telling touches, from the piles of books and trunks at the start of Act 2 doubling as Ferdinand’s Prosper-edicted tasks and the mechanicals’ upending of Caliban; to the marvelous visuals of the California state seal integrated into the mix for the climax. The performances and intent rang true to the proposed objective, but at nearly three hours, it wasn’t always easy to remember that.

Its creators are certainly aware of these issues, as Garcés notes after the first leg of the tour.

“We learned a lot, starting with less is more when people in the audience have to get up at 4 or 5 in the morning,” Garcés concedes. And yet, even small children leaving the space in Arvin were doing so with one eye over their shoulder, not wanting to miss what was going on, a sure sign that the storytelling was working.

Besides sharpening the company’s resourcefulness—“Housing is always a work-in-progress, in every town,” says Garcés—and ingenuity (getting a 53-foot truck with your entire physical production down narrow dirt roads, for instance), other lingering benefits have accrued.

As Howard explains, “Shakespeare raises all kinds of important questions of craft, raises the bar, really. And when do people get their Shakespeare? What does it leave them with? And then you see how coming to these places that we haven’t been to for a while—10 years between visits is a long time for a small town—it increases connection and reduces isolationism, and crosses some of those boundaries between urban and rural. And then there’s the large number of young people who have been attending this tour. It’s beyond value.”

Finally, there’s the ineffable synergy that the Cornerstone process ignites, even as it creates still more challenges. Garcés puts it in perspective: “We’re going to be recasting Antonia for the second leg, because E’Vet [a single mother in a custody battle at the time she was cast] has since won custody of her kids. And while that’s another problem for us to solve, we’re thrilled for her. What we do is what theatre always can do, but sometimes we don’t activate the potential as much as we could. The act of making instigates change, and my mantra is, ‘Change is good. Anything can happen.’ We’re already discussing where this might take the company next.”

Donnelly has some ideas.

“From this tour, it’s evident that there are always new and interested communities to collaborate with and learn from,” she says. “We haven’t told stories of California’s ‘gold country’ yet, or the Sacramento Delta area. San Bernadino is a huge county where we’ve not done an institute yet.” They’re even thinking about “what it would mean to do an institute outside of California—Baja comes up a lot, as does the idea of returning to Cornerstone’s first collaborating communities: Marfa, Texas; Marmarth, North Dakota; Norcatur, Kansas.”

Wherever it goes next, participants are likely to learn, as Donnelly put it, “The institute summer residency kicks your ass, but it’s tons of fun, and there’s nothing like it.”

That last remark could also describe this incomparable company—a California vanguard and a national theatrical treasure.

David C. Nichols is a performer-turned-arts journalist and critic whose writing has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, L.A. Weekly, Variety, Backstage, the Sondheim Review and elsewhere.