Even God was impressed. There He was, blending in with the rest of the crowd on a narrow downtown street last December.

After 17 years and more than 100 world-premiere productions in a rented building in New York City’s Tribeca neighborhood, the Flea Theater—defiantly eclectic, intentionally small—was holding a well-attended groundbreaking for a permanent new home. Artistic director Jim Simpson, his wife, the actress Sigourney Weaver, other Flea staff and New York City officials donned hardhats, grabbed hammers and knocked down a wall—a symbolic wall, made of poster board—to reveal the 222-year-old building behind it that the company will spend millions of dollars renovating. On the windows of the building at 20 Thomas Street, in big red letters, was the Flea’s motto: “Raising a Joyful Hell in a Small Space.”

That small space will be larger than the company’s original home four blocks uptown, but will firmly remain an Off-Off Broadway house.

“We went into this 17 years ago with the idea of celebrating Off-Off Broadway and honoring it and investing in it,” Simpson says. “We’re going to continue to do the same.”

“These small venues are like a little greenhouse where everything germinates,” Weaver adds, “that then feeds the bigger theatres, and the industry, and the cultural landscape. Wherever you are in the country, you just need to get together a group of passionate people.”

When the renovations are complete, the building will contain three theatres: The Sam, with up to 120 movable seats, named after agent Sam Cohn, whom the Flea credits with helping to save them after the 9/11 terrorist attack; The Pete, with up to 72 movable seats, named after playwright A.R. (Pete) Gurney, who has had eight works produced at the Flea, and who has credited the Flea with reviving his career; and, in the basement, the Siggy, with 44 fixed seats, named after Weaver, who got the whole thing started with a million-dollar gift to her husband in 1996.

“When I first began acting Off-Off Broadway,” Weaver says, “the spaces were always terrible—they were unheated, there were no bathrooms, no dressing rooms. The walls were crumbling. My husband and I thought: This work is so important, and it deserves a state-of-the-art theatre with proper working conditions, because you don’t really get paid when you work Off-Off-Broadway.”

The groundbreaking ceremony played out before a crowd of hundreds of young people wearing red knit caps stitched with the Flea’s logo. These were primarily past and present members of the Flea’s unpaid resident acting company, the Bats. A recent college graduate named Matthew Jeffers was among them. He had responded to an open audition a week after he moved to New York in October, and got an e-mail from the company manager a few days later: “Congratulations, you caught Jim’s eye.”

Now, in December, on his third callback for a role in the Flea’s next production, Jeffers was thrilled to have been invited to the groundbreaking. “The only thing I knew about the Flea before I auditioned was that they were named after an insect. Now I look at them in awe,” Jeffers says. He was impressed with “all the press, the government officials and the talent of the people in the Bats.”

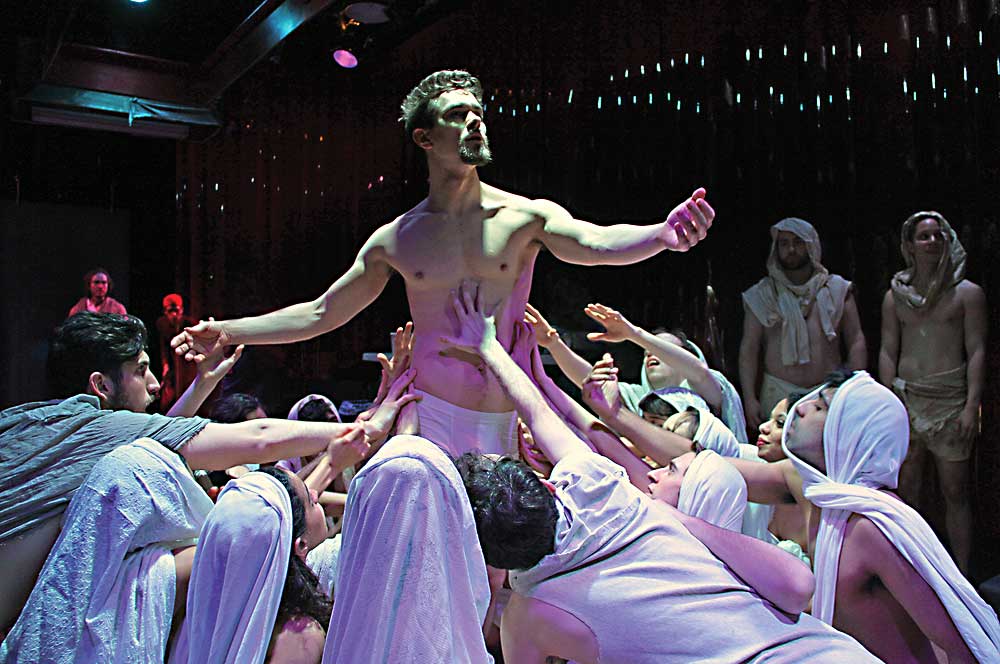

Not long after, Jeffers was accepted into the Bats, one of 40 picked out of some 600 who auditioned. He was cast in the Flea’s most ambitious show ever: a six-hour epic called The Mysteries, running April 3–May 25. Stitching together the work of 50 playwrights, including David Henry Hwang, Craig Lucas, Jeff Whitty and Billy Porter, the series features a cast of 54. Like the medieval mystery plays that are its inspiration, it’s a retelling of the Bible.

And the awestruck Jeffers, 4’2” tall and 22 years old, is playing God.

At a time when it is increasingly difficult for any theatre to survive, the Flea’s planned $18.5-million expansion is to some an inspiring tale. Admirers might point to the theatre’s track record of sometimes difficult, controversial work, though Simpson prefers the term “adventurous.”

“I’m interested in the entire range, not just the avant-garde,” Simpson says.

Simpson and Weaver themselves are clearly proudest to be providing theatrical opportunities for a diverse group of early-career artists like Jeffers. “We have about 200 young people working here all the time—actors, writers, designers, directors,” Weaver says. “They’re the future. It’s good to invest in the future of the arts.”

But the brighter spotlight on the Flea, and the new expansion’s price tag, have also attracted criticism from those who point out that the Flea doesn’t pay many of those young artists—and in fact requires several hours of additional labor from the members of the Bats each week, referred to as “Bat hours.”

“Why, if there’s $18 million for a new building, isn’t there some amount of money to pay these kids to work?” asks theatre artist and critic Isaac Butler, who wrote an in-depth critique for the website Hooded Utilitarian. Simpson seems stunned by the attacks, but not surprised at the argument. “This particular aspect of the Bats has been a fight for me from the start, to get people to understand.”

It might help to know where he’s coming from. Simpson started out as a child actor at the age of 10, when he tagged along with his older brother to an audition for a bus-and-truck production of Bye Bye Birdie and was asked to sing “Happy Birthday” as loud as he could. He got the part, and many others in musicals over the next decade: The Sound of Music starring Jane Powell, Fiddler on the Roof with Theodore Bikel, Carousel with John Raitt.

This was in Honolulu, where Simpson attended Punahou School several years before Barack Obama. He also got television roles: “From 14 to 21 you can see me growing up as a bad guy on ‘Hawaii Five-O.’”

When San Francisco’s American Conservatory Theater visited Hawaii to perform the classics, Simpson made a discovery. He saw that good theatre directors “always made you feel they cared about more than just hitting your marks and getting your laughs.” In TV, by contrast, “they just banged it out.” He also became convinced of a truism that has guided him ever since: “If you follow the money, you may end up with the money, but as an artist you won’t be moving forward.”

Later, as a theatre major at Boston University, Simpson studied with Maxine Klein, author of Theatre for the Ninety-Eight Percent—by which she meant the percent of people who don’t attend any theatre now—which argued for “a communal people’s theatre for our emerging communal society…inexpensive, idealistic and pragmatic,” that “ignores class lines” and “affirms people’s worth.”

He spent the summer of his sophomore year in Poland studying with director Jerzy Grotowski, who aimed to strip theatre to its essentials, the basic interaction between performer and spectator. Anything else—costumes, orchestra, sets—would get in the way of what’s important, Grotowski believed. The Polish master also encouraged Simpson to experiment. “Grotowski’s maxim for an artist was: Go where you haven’t gone before.”

Immediately after B.U., Simpson attended the Yale School of Drama, where the new dean, Lloyd Richards, focused on new American plays. At Yale, Simpson made an impression on classmate Carol Ostrow.

“He had a great head of hair—it was dark then,” Ostrow recalls of her now-graying colleague. He was also “a quiet person who only came to life in the rehearsal room.” She played Ophelia in his Hamlet. “He was a very smart and cocky director. He acted for us. He would show me, ‘This is what I want.’”

After Simpson graduated, he began directing Off-Off Broadway, braving shocking conditions—“inadequate electricity, rats, flooding”—because “you get to choose whatever play you want to work on. You can’t do that anywhere else.” He started a theatre company on the Lower East Side in a dive on Essex Street, but the first well-reviewed show prompted his landlord to triple the rent, and that was the end of that company.

During this time, Simpson was spending his summers assisting Nikos Psacharopoulos at the Williamstown Theatre Festival in Massachusetts (“he had a lot of young people in his theatre”), and, since the pay was so low, serving as a bartender at a local hangout. One night at the bar in 1982, a previous graduate of Yale who was performing at the festival, asked him to dance. He said no.

Sigourney Weaver had become a movie star some four years earlier thanks to Alien, but she too had worked Off-Off Broadway, and had similar experiences. Thirty seconds after Simpson turned Weaver down, he recalls now, he changed his mind; they danced, awkwardly, and eventually married in 1984.

Two years later, Simpson quit Off-Off Broadway. The breaking point came when, directing Mac Wellman’s play Three Americans at Soho Rep, “I was calling in favors to actors I knew to work on this very difficult piece, and nobody was earning a living wage. It got a terrific New York Times review—and nobody came. I thought, I’m too old for this stuff.”

For the next decade, he did work for HBO, the movies, Off-Broadway, occasionally regional theatre. Then, in 1993, Simpson, Wellman and designer Kyle Chepulis were driving back from working on a site-specific show at the Natural History Museum in Washington, D.C., and complaining about the state of New York theatre. By the end of the car ride they had concluded: “Why not start a company of our own?”

Wellman gave the theatre its name, the Flea—meant to suggest a small irritant—and its motto (the “joyful hell” line). Simpson found the space on White Street—a ground floor and two basement floors in a building across the street from a strip joint and around the corner from a brothel. With Weaver’s million-dollar investment, he figured the Flea would run for five years at most.