In one chapter of his book Outliers, Malcolm Gladwell takes the reader on step-by-step replays of several plane crashes. As Gladwell explains, planes rarely go down because of catastrophic mechanical failure or gross incompetence. Typically, crashes begin against a backdrop of slightly unfavorable but hardly unusual conditions: bad weather, a pilot and co-pilot who’ve never worked together, the end of a long shift for one or both of them. Then, a series of small human errors—seven, on average—pile up. Each error would be easily correctable on its own, but in the aggregate, they combine alchemically and open the door to disaster.

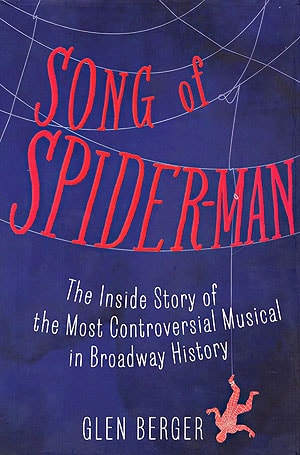

In Song of Spider-Man:The Inside Story of the Most Controversial Musical in Broadway History, Glen Berger walks us through a catastrophe of a different kind: the musical Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark, a critical, financial, technical, legal and medical debacle that temporarily surpassed the S.S. Titanic as America’s favorite metaphor for hubris. That’s despite grossing more than $200 million over more than a thousand performances to a cumulative audience of more than two million people—a good many of whom actually liked the show.

As Julie Taymor’s co-bookwriter, Berger had a front row seat for the rise and seemingly endless fall of Spider-Man, and much of his memoir/autopsy closely parallels Gladwell’s airline-disaster analysis. In fact, Berger’s snappy prose shares more than a few similarities to Gladwell’s, including a penchant for rhetorical questions and incredulous asides, a webslinger’s skill for linking seemingly unrelated ideas, and a liberal use of italics. For much of his telling, Spider-Man sounds like a six-year slow-motion plane crash brought on by a perfect storm of dozens, if not hundreds, of critical human errors, under a steady bombardment of adverse circumstances. And it raises questions, both implicitly and explicitly, about what might have happened if things went a little differently.

Suppose, for example, original producer Tony Adams, a charismatic Irishman who charmed the stage rights from Marvel despite a one-show Broadway résumé, hadn’t died in October 2005, shortly after he also lured both Taymor and U2’s Bono and The Edge onto the creative team. Would his magic personal touch have kept up the investors’ confidence and smoothed out creative conflicts? What if line producer Martin McCallum, a financial veteran of the megamusicals Les Miz and Miss Saigon, hadn’t washed his hands of Spidey in 2009?

And what if Michael Curry, Taymor’s co-designer on The Lion King, hadn’t left the project early after a falling-out with his longtime collaborator? Would he have let the design get anywhere near the point where a giant, million-dollar, web-deploying ring is declared unworkable in the Foxwoods Theatre and torn down immediately after it’s installed? Or where one actor breaks a toe and fractures a foot because a ramp lowers just a little too late, and another plunges 30 feet onto solid concrete because a stagehand momentarily forgets to clip one of the innumerable harnesses that must be clipped and unclipped in the dark, eight times a week?

More fundamentally, would there have been so many opportunities for error if the conceptual tail hadn’t wagged the narrative dog through so much of the show’s development? As Berger tells it, he took on the role of “words guy,” charged mainly with carrying out Taymor’s vision. But what if that vision hadn’t involved an Act 2 finale that relied, indispensably, on the aforementioned million-dollar web ring, which all were warned might not work, especially when the subsequent workarounds proved so maddeningly anticlimactic?

Furthermore, what if Taymor hadn’t been so inspired by the myth of Arachne that she made the weaver-turned-spider a central character—one whose high-maintenance set pieces dictated much of the show’s structure? What if she hadn’t latched onto the idea of a “Geek Chorus” of contemporary Spider-fans, a device that sucked up untold megawatts of creative energy, only to be almost universally derided and unceremoniously cut from the rebooted version? How many other narrative problems might have been solved in the time spent trying to wrestle these elements into submission?

As expected, many of the what-ifs Berger poses lead back either to Taymor’s actions or to other people’s reactions to them. Still, he makes it all sound both inevitable and irreducibly complex. Taymor was Spider-Man’s pilot, by dint both of her position as director/co-bookwriter and her identity as a theatrical visionary. Yes, Bono and The Edge were rock superstars, but Broadway wasn’t their home turf, and they come off here as creatively invested, but too busy and too polite to consistently push back with equal force against Taymor’s excesses. Meanwhile, Berger—who was captivated instantly by Taymor’s transcendent, joyful energy, who bonded creatively and personally with her like no other artist he’d ever known, and who hoped to finally shore up his family’s fragile finances with a Broadway hit—had no inclination to risk any of it until it had already begun to evaporate.