Do you want one more tale of a Vietnam girl?

—Miss Saigon by Claude-Michel Schönberg and Alain Boublil

Growing up, my dad always told me, “Every Vietnamese family has a remarkable story.” I was raised in Orange County, Calif., the home of Disneyland, the Angels baseball team, and Little Saigon—the largest population of Vietnamese people outside of Vietnam. It means that we were surrounded by people who were refugees, veterans, war survivors—people who were forced to uproot themselves from their homeland, travel across the Pacific to a country where they did not speak the language, and build a new life. And every one of them, according to my dad, carried a story of how they got there, of the sacrifices they had to make, the family they lost or abandoned.

Then my dad would follow that statement with, “One day, you can tell our story.” My family’s story isn’t one that you would have seen in a Hollywood movie or a Broadway musical. For one, it doesn’t conform to stereotypes that white executives and producers have about us. There are no silent and sexualized Asian women. There are no conniving and emasculated Asian men. And there are no white men.

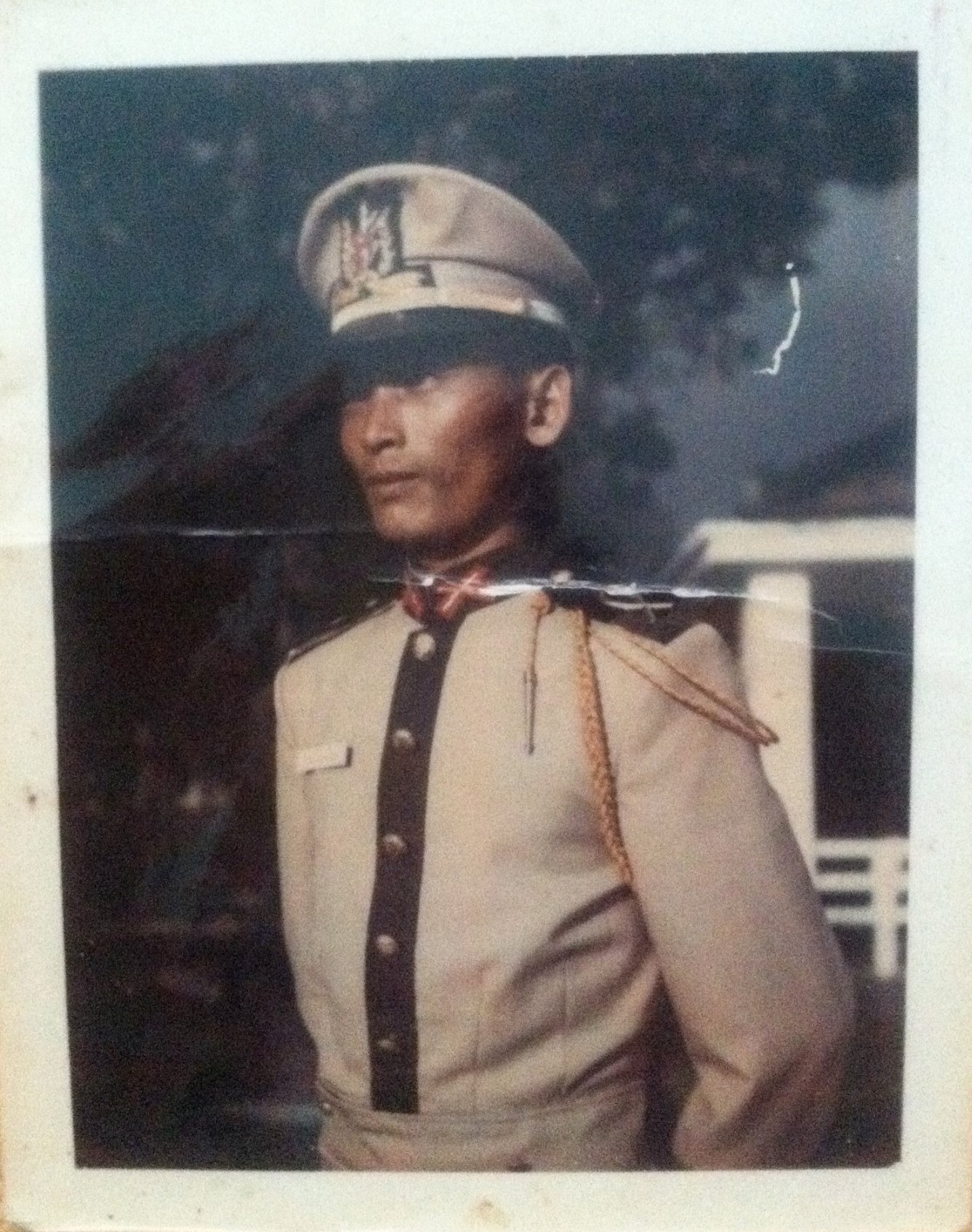

Instead there’s a South Vietnamese English-teacher-turned-soldier, my father, fighting the Viet Cong. He meets a South Vietnamese woman, my mother. They fall in love and exchange letters for two years, before he travels 200 miles, from Qui Nhơn to Đà Lạt, to ask for her hand. There is a turning point, April 30, 1975. The teacher is imprisoned. His wife, now a mother of two, is left alone to support her family.

You won’t see this love story on Broadway. Instead, what you will see is Miss Saigon.

I saw Miss Saigon three weeks ago, in its current revival at the Broadway Theatre, that “epic love story” about a white G.I. and a Vietnamese prostitute who kills herself in order to grant their son passage to America. I attended with two friends, both Vietnamese. We arrived knowing that this production, even though like the original it was created and directed by white men, had reportedly tried to be more respectful to the Vietnamese culture (for one, they replaced hitherto gibberish lyrics with actual Vietnamese words). And there were Asian actors, even some Vietnamese, in all the Asian roles.

But I left with a headache, the kind of headache you get when you are forced to keep your emotions silent, so they travel to your cranium. To say that my friends and I didn’t like Miss Saigon is an understatement. If the show was trying to tell the story of Vietnamese people, we did not recognize ourselves or our parents in any of the faces we were seeing on that stage. Instead, all we could see were desperate, pathetic victims—people who were completely different from the resilient, courageous, multifaceted men and women of Little Saigon.

And if I needed a sign that Miss Saigon was not for me, it was in the lobby. They were selling a baseball shirt featuring Ho Chi Minh and the communist flag, the very symbols my family fled from.

But people love this musical. What was I not seeing? I contacted Viet Thanh Nguyen, who won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction last year for his book The Sympathizer, about Vietnamese refugees. He told me he saw Miss Saigon in 1996 and he remembered feeling “amazed by how audience members around me cried during the show,” he wrote in an email. “I thought it was terrible, fulfilling every Orientalist trope that I had studied and was opposed to. The cross-racial casting issues aside, it fits perfectly into the way that Americans, and Europeans, have imagined the Vietnam War as a racial and sexual fantasy that negates the war’s political significance and Vietnamese subjectivity and agency.”

Oof. Playwright Qui Nguyen, whose play Vietgone is being produced around the country this season and which tells a version of his own parents’ Vietnamese refugee story, echoed those comments even more pointedly. “I hate Miss Saigon,” he told me. “I wish that wasn’t the case. I wish that it was a piece of art that felt empowering and complex and beautiful to me as an Asian American, but it’s not. It’s melodramatic white-savior fantasia claptrap that’s barely more than a modern-day Mikado.”

Much has been written about Miss Saigon, primarily by white writers: about the yellowface controversy, about the actors involved. But very few Vietnamese-Americans have weighed in. We are the sixth-largest immigrant group in America, numbering 1.3 million. And yet popular narratives of the Vietnam War typically exclude us. And as Miss Saigon tours the country next year, the most popular narrative of all will continue to shut us out.

As Viet said on NPR, America may have lost the war in Vietnam, but “wherever you go outside of Vietnam, you have to deal with American memories of the Vietnam War.” And those memories center on American guilt and self-flagellation. As Chris in Miss Saigon moans, “I’m an American, how could I fail to do good?!” Miss Saigon’s guilty-American tropes don’t exist in a vacuum but in the context of films like Apocalypse Now, Platoon, and Full Metal Jacket—properties in which white men are the anguished protagonists trapped in a hellish foreign landscape and the most iconic line from a Vietnamese person is “me love you long time.”

Whatever their various merits, these films essentially reduce the Vietnam War to a narrative about whether or not America should have been involved, and they make the Vietnamese background players, bystanders in our own country’s history. It’s complicated because there are three sides to this story: the South Vietnamese side, the North Vietnamese side, and the American side. But one thing is not complicated: Westerners have been at the center of this narrative for too long.

Miss Saigon‘s Americans feel the need to “do good,” to live in “a place where life still has worth,” while the Vietnamese, according to the Engineer, “thinks only of rice and hates entrepreneurs.” We are portrayed as primitive villagers, prostitutes, and pimps—as the self-hating Engineer puts it, “greasy chinks.”

The most damaging part is this: In Miss Saigon, Vietnam is a place not worth saving, and America is a holy grail worth killing and dying for. We hate ourselves because we are not white (the Engineer), and we will even shoot ourselves in the name of America (Kim). Why would you want to be with a Vietnamese man when you can be with a white man? Why would you want to be Vietnamese when you can be American instead?

Is it any wonder that I, and so many other Vietnamese people, hate Miss Saigon?

When I was in grade school, I had to write an essay about a woman that I admired. I wrote about my mom. I wrote about how, when the war ended, my father was jailed and placed in a gulag-style labor camp. The American narrative of the Vietnam War would have you believe that it was America’s unfortunate duty to save the poor Vietnamese villagers from the evil communists. Except they conveniently forget that there were strong Vietnamese men who fought the Viet Cong too. Those men didn’t dream of being Americans; they wanted their own country to be free. And unlike the American soldiers, the South Vietnamese soldiers could not go home. After the war, either prison or refugee status awaited them. My father suffered the former.

In his absence, my mother made a living selling goods on the black market while taking care of her two daughters. Then, every two months, she would travel more than 156 miles, a two-day journey, to visit her husband at the labor camp, where he worked 10 hours a day in the fields. He was being fed just one bowl of rice a day. She would bring him food, and medicine. They would talk for 15 minutes. They would repeat this ritual for six years. “It was hard,” she recalls simply. “But he would have starved without me.” Her love saved him.

Asian women like her are rarely presented in American culture—as people who are resilient, resourceful, strong, not victims. Instead, in Miss Saigon, Kim, a woman with no last name, sings about her longing for a man to save her. She says nothing when she is abused by the men around her but suffers silently, beautifully. And when living in America isn’t an option, she kills herself; for her, being dead is better than being Vietnamese. And the largely white audience has a good cry and feels like they’ve had an educational experience.

Except what have they learned, really? That Vietnamese women are victims, Vietnamese men are villains, and Americans are well-meaning buffoons. Perhaps if I were being generous with Miss Saigon, I could read it as a cautionary tale for Asian people: Don’t depend on whiteness; it will kill you.

Many actors have defended Miss Saigon for the jobs it’s provided for generations of Asian-American actors. But what kinds of jobs are these? Playing stereotypes, people who hate their skin and idolize whiteness to the point of suicide? Almost 30 years after Miss Saigon first premiered, whitewashing, yellowface, and the white-savior narrative are still huge problems for Asian-American actors and audiences. And if there is no Miss Saigon or King and I on Broadway, Asian-American actors rarely get cast as leads, or at all.

Asian Americans are still fighting an industry that would rather cast white actors to play us and would rather we play sidekicks and prostitutes—stereotypes that narratives like Miss Saigon have only helped perpetuate. Properties like Miss Saigon offer a way for white producers to feed us stereotypical scraps while continuing to starve us. They profit off of our bodies while silencing our voices.

If there are signs of hope, they’re not coming from commercial producers or white writers. For example, more multifaceted stories about Vietnam and its people are coming from playwrights like Qui Nguyen and Don Nguyen, from novelists like Viet Thanh Nguyen, Thi Bui, Andrew X. Pham, and Bich Minh Nguyen. They’re coming from Vietnamese writers who are telling their stories and demanding to be heard.

As Qui told me, he will not let his two sons watch Miss Saigon. “Though this is one of the rare opportunities to see Asians onstage, there’s no way I’d let them see it,” he explained. “I don’t want them to ever feel like they’re the accessory to the dominant culture, which is what Miss Saigon makes me feel. I want them to know that they are the leading men in their stories. I’d honestly rather just have them watch cartoons in the meantime and wait for me and my fellow Asian-American artists to fill in the gaps still present in both Broadway and Hollywood.”

In Little Saigon, Orange County, there is a Vietnam War memorial with a bronze statue quite different from the one in Washington, D.C. Instead of a statue of American soldiers, it shows an American soldier and a South Vietnamese soldier standing side by side, equals. It is time that Vietnamese people are the heroes in our own narratives. It is time we take our stories back.