On May 16, 2016, hundreds of alumni of the University of Michigan’s musical theatre program gathered at the August Wilson Theatre on Broadway to celebrate Brent Wagner, the department chair, on the occasion of his retirement. Many months of planning went into the two-and-a-half-hour evening of songs, sketches, and speeches dedicated to Wagner’s three-decade career at the school. Spearheaded by Gavin Creel and Celia Keenan-Bolger, the gala concert brought alumni and current performing arts students together to perform onstage and work in the wings to honor Wagner.

“What was valuable about that was that people were coming together to celebrate their relationships,” says Wagner. “I may have been the catalyst for bringing it out, but they were sharing their love for each other. That made me the most proud of anything I’ve ever done, because it shows that all the things I was hoping to pass on to all of them had value.”

The evening was more than an homage to Wagner, who built the BFA musical theatre program when he arrived in 1984. He said it was the first time he truly recognized the impact he’d had on his students and on the field.

“That was transformational to me,” he says. “I thought: If that is the impact—which I didn’t realize was so big—then I maybe shouldn’t leave it quite so soon.”

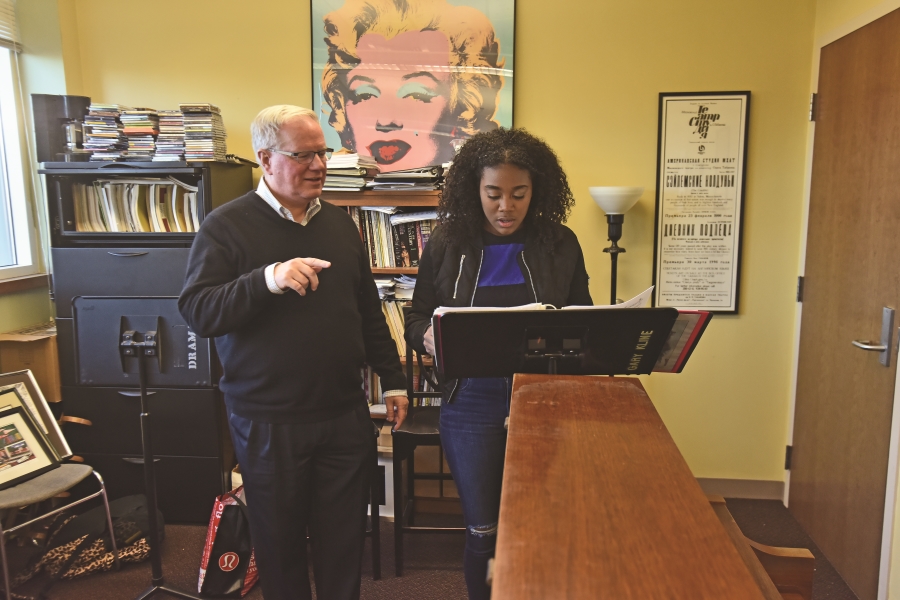

So he didn’t. Wagner has stayed on part-time, welcoming the class of 2020 this fall and teaching his favorite course, an introductory class for first-years, for the 34th time.

In building the BFA curriculum all those years ago, Wagner fought for musical theatre to have a rightful place in higher education. At the time, not even all music professionals and acting professors deemed musical theatre worthy of a place in academia. But now that thousands of hopeful high school students vie for coveted spots in musical theatre programs at colleges across the country every year, hundreds of schools all over the U.S. are offering musical theatre degrees, both B.A. and BFA. And behind these triple-threat students is an army of theatre educators who lead the programs.

Gary Kline, assistant head of acting and musical theatre at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, helps with CMU’s college audition process. When working with young performers interested in auditioning for the program, he says, “I like to tell them that the best thing they can do is believe that there is some kind of a plan and that they will end up where they belong. Not everybody is going to get into CCM [the University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music], Michigan, or Carnegie Mellon, or whatever ranking there is out there with top schools.”

James Randolph, an assistant professor at New World School of the Arts in Miami, has worked with students in the program’s high school magnet training arm and as part of NWSA’s performing arts training at Miami Dade College.

“In the pedagogy of it all, you only have so much psychological and intellectual development at the age of 16,” he says. “It’s about helping them to ground themselves and get ready to go into a world of more exclusion rather than inclusion. High school is inclusive, college is exclusive, as a general rule in America.”

Even on top of that, college performing arts programs can hold super-exclusive status. And the pressure of attending schools with such a high reputation only adds to the challenges for students adjusting to a new environment. The formative college years are very different for performing arts students than for typical university students, as faculty in performing arts training programs take on a role well beyond teaching, often working with students ’round the clock in both classrooms and rehearsal spaces.

“It was Sondheim who said teaching was really about awakening curiosity in other people,” says Wagner. “He felt that art itself is teaching, because we all learn, in whatever stage in life we are, from the arts.” In addition to awakening curiosity, Wagner feels he has an obligation to instill in his students standards of professionalism and respect, and to teach them to leave the field better than when they entered it.

Kaitlin Hopkins, who helms the musical theatre department at Texas State University in San Marcos, recognizes that her teaching is about more than honing students’ technical skills.

“My responsibility as an educator incorporates many different aspects of their development,” she says. “I am responsible for developing their craft, their technical skill set, and their unique voice as artists.”

Peter Reynolds, the head of the musical theatre program at Temple University in Philadelphia, transformed the school’s musical theatre concentration into a BFA degree just this year, building on the school’s 50-year concentration in acting. “We’re about honoring what they bring to the table and where they come from, and training them to be the best they can be—training them to be soldiers for a really brutal, brutal profession,” says Reynolds.

Another way performing arts training can be different from other disciplines: Some schools require students to sign a contract to uphold the program’s standards. The 10-page document at Texas State, for instance, outlines the department’s definitions of professionalism and integrity. At NWSA, students agree that they will comply with the rules of the program and commit to working a set number of hours backstage and complete technical theatre duties. In all, students are acknowledging that they are part of an ensemble of sorts, made up of teachers and students alike.

But mostly students learn what’s expected of them by example. “I feel like we have an obligation to be role models for them, because we spend so much time with them,” says Wagner. “If we are going to insist on standards from them, we have to demonstrate those standards are a part of our lives and a part of everything we do.”

Perhaps the biggest responsibility for teachers is overseeing the development of a student over their four years of training.

“You can actually see the difference from year to year, that they are just growing and changing,” says Wagner. “That is a marvelous gift to be part of, and also I think it comes with tremendous responsibility on our part.”

Christian Borle (Something Rotten!, Peter and the Starcatcher) was 17 when he began at CMU. “I didn’t know what he would become—he was wildly creative but didn’t really have a major voice,” says Kline. “We worked for four years, and I felt like we created a voice in some ways with him. But he was so incredible with his imagination. I just didn’t know where it would go, and I didn’t hear from him for a while. To watch him from 17 to becoming this leading man—guys like Christian make me very proud.”

Borle credits Kline’s instruction for his success. “Gary Kline literally made me the performer and singer that I am,” says Borle. “I haven’t really studied voice since Gary—and my voice, because of the foundation he gave me and understanding of it, has continued to grow and change over the last 25 years. I learn something different with every new show because of the base that he gave me.”

Hopkins believes you can’t develop an artist’s technique unless you’re willing to help develop the person. “One must have a holistic approach to performing arts training,” she says. This can get very specific: When freshmen arrive at Texas State, they undergo numerous evaluations by volunteer specialists, including TMJ (Temporomandibular joint) exams, postural exams, and blood tests to determine possible allergies. They also get their hearing tested, and speech pathologists examine a vocal strobe. These tests help the staff to get a sense of how to work with each student before diving into four years of intensive training. “What if I have a kid with weak ankles?” says Hopkins. “I shouldn’t wait until they sprain their ankle two or three times in ballet class.”

Dance studios are also stocked with granola bars and apples to ensure that students are nourished before class. “I truly believe that the habits they create here are the habits they will take everywhere,” says Hopkins. “No matter how talented and how well trained they are, if they don’t know how to take care of themselves, what good is it?”

At Temple University, a nutritionist and wellness coach are on staff to help students stay fit and healthy. Seminars are offered on nutrition, and students can work with Maggie Anderson, the assistant professor of musical theatre and movement, to design a personalized workout regime.

In addition to physical wellness, performing arts instructors take on a responsibility to make sure that students are emotionally and mentally prepared for both their academic and performance obligations. The competitive nature of performing arts classes can take a toll on students.

“Their emotional centers are more exposed, and you want to try to keep them centered because of this wild thing of being an actor and taking on everyone else’s angst and problems,” says CMU’s Kline. “You have to really be able to disengage yourself and live another life also outside of this school. That is very hard, because Carnegie Mellon is incredibly intense and the intensity can get to them.”

Many of the universities have counseling programs on campus to help ease students struggling with transitional woes and school stressors. Texas State also offers relief in the classroom, mandating that each session in performing arts classes begin with meditation. Often the performing arts faculty can gauge when students are overwhelmed; individualized attention in selective programs leads to close teacher/student relationships.

“When they come in and they are depressed, I know it,” says Kline about his one-on-one vocal lessons. “When they are sad, I know it. When they’re happy, I know it. When the weather is terrible, I know it. When they’re overloaded and stressed about the workload in other classes, I know it. In a way, a singing teacher becomes a mentor, no doubt about it. It can become very close.”

Having an understanding mentor can certainly ease stress for students. “I always knew heading into our lessons what mood Gary was going to be in, and that he was always going to be incredibly gracious and supportive—so there was no guessing there,” says Borle of Kline’s voice lessons. “In this crazy world, consistency and constancy are my favorite things in a person, and he’s got them in spades.”

Sometimes a teacher’s best intentions for students go unnoticed at first. When Peter Reynolds cast Da’Vine Joy Randolph (Ghost the Musical) in Temple’s production of Stephen Adly Guirgis’s Our Lady of 121st Street instead of Ragtime, she didn’t talk to him for a month.

“He wanted me to have the experience of being an actor in a straight play—I didn’t know that at the time, and I was so angry with him,” confesses Randolph. “I was blinded by my own ambition or what I thought I needed or wanted.” A good teacher, she’s come to realize, “will pull you out of your comfort zone, but there is a method to his madness.”

Another approach is to allow students the freedom and flexibility to explore on their own. Kline says he tries to inspire students to widen their outlook on pursuing a career in the arts. “I try to encourage young people [to understand] that being an actor is not the be-all, end-all, there are other things to do,” he says.

Likewise, Wagner built the University of Michigan BFA program to allow theatre students to take advantage of the university at large. He makes sure that students are able to get away from the rehearsal room and experiment, because “once you get out of college there is no time to experiment,” he says. “You are on a pathway to a career.”

In NWSA’s magnet program, Tarell Alvin McCraney choreographed two ballets, starred in a musical, directed plays, and wrote short plays before receiving his high school diploma. Though his concentration was in musical theatre, McCraney’s exploration helped him to narrow his focus to playwriting (which has worked out well for the author of The Brother/Sister Plays and Head of Passes).

“I did everything that was legal to do,” McCraney says with a laugh. “To me, that’s an experience that I don’t think a lot of young people get in the arts.”

McCraney took heed from James Randolph, his teacher and mentor at NWSA, who juggled administrative tasks with directing, teaching, and organizing competitions for the students. “I always remember watching him thinking, ‘Wow, he has so much energy to do all these things—he clearly loves to teach,’” says McCraney.

Besides the flexibility to explore different postgraduate pathways, theatre educators are diligent in preparing students with material for their senior showcase, and in educating them with pragmatic information on everything from navigating contracts to filing for unemployment and paying taxes.

And even after students receive their college diplomas, the learning and the relationships often continue. “When we accept someone, we are not accepting them for four years—we are accepting them for good,” says Kline of CMU’s group of alumni.

Wagner says he’s excited when former students return for a visit, especially to work with current students. “That’s one of the most thrilling elements: to have guided students for four years, they go out and start their own careers, and then they come back to work with the students,” he says. “It is so marvelous to see how they’ve taken all the things we’ve taught and all the things they’ve learned since they have left, and put them all together in one big picture to pass on.”

Amy Rogers, who heads the musical theatre program at Pace University in New York City, says the evolution of teacher/student relationships reflects her life’s work. “It goes from teacher to mentor to friend. Watching that cycle grow has been spectacular.”

For McCraney, the roles have been reversed for him and his mentor, James Randolph. In 2015, Randolph played the character Headmaster Marrow in a production of McCraney’s play Choir Boy at GableStage in Coral Gables, Fla., and McCraney directed him as Claudius in a production of Hamlet that toured for high school students in the region.

“He was just so generous in becoming a colleague,” says McCraney. “He respected me and the vision I had, and kept everything collegiate.”

Says Randolph, “Even though we are divided by age and generation and by [the roles of] professor and student, we try to be affable and supportive, almost like surrogate parents or extended family members—ones that have tough love.”

Things have also come full circle for Borle, who counts himself lucky to have remained close with Kline. “It is always incredibly lovely when you shift out of the teacher/student dynamic into realizing that you are both now just adults in the world who have this dynamic,” says Borle, currently starring as Marvin in the Falsettos revival on Broadway. “He introduced me to Falsettos in 1991, and handed me the sheet music to ‘What More Can I Say?’ I can’t believe he is coming to New York City to sit in the audience and watch me do it in this arena.”

Rogers can add “cheerleader” to her long list of theatre educator duties: She recently watched her former student Cathryn Wake make her Broadway debut in Natasha, Pierre & the Great Comet of 1812. “My years at Pace were the most formative of my life,” says Wake. “I became the person I am today during my time there, and I was overjoyed to have my teacher and friend share this experience with me.”

Undoubtedly, theatre educators are proud of students who make it to Broadway and have a shot at giving an “I would like to thank…” speech at the Tony Awards. But they are just as proud of students who work consistently in the theatre field, both onstage and off, as they are of those who use their training in other fields.

“I think if we are creating the visionaries of tomorrow, we can’t be too focused on how they are going to use this training,” says Wagner. “They may be the ones who are the next generation of Lin-Manuel Mirandas, who take what we are giving and find all-new ways of performing, writing, and creating that we want to make sure we are guiding them to. All that really matters is that they benefit from the work we are doing, and value it however they go on to have careers.”