“Truth be told, the issue of ‘what to call ourselves’ has been around all my life,” the veteran Chicano theatre scholar Jorge Huerta told me via email last month as I surveyed leading voices in the field about an important style decision for this magazine: Would we get on the Latinx bandwagon or not?

You are forgiven if you haven’t clocked the emergence of this term, or the way our increasingly enlightened views of gender oppression and expression have collided with a convention inherited from a gendered Romance language. But these standards are changing fast, and we have felt compelled to respond. First, I’ll cut to the chase: We are adopting Latinx (variously pronounced Lat-in-ex or La-TEEN-ex) as our generic adjective for people of Latin American descent, and you’ll see the word throughout this special section on Latinx theatre in the U.S.

Why? Quick version: Latino, which has emerged in my lifetime as the preferred term over Hispanic (properly a language-speaking category, not an ethnicity) for people of Latin American descent, has since split into the courtly Latina/o as a way to recognize the women previously lumped under a male-gendered word, though it’s never taken hold as a style in most publications, including our own. More recently the predominance of the a/o gender binary, which admits only either male or female, has been challenged. Hence Latinx, which, though arguable from a linguistic point of view (more on that below), has emerged as the most inclusive adjective for people of all gender expressions. As director David Mendizabal put it to me: “By saying ‘Latino’ we continue to perpetuate a male-dominated machismo culture and patriarchal hierarchy. It allows for the continued erasure of women and gender-non-conforming people. ‘Latina/o’ is a step in the right direction, but it keeps language/identity and culture locked in a binary—this or that. For me ‘Latinx’ expands the ‘box’ and begins to open up dialogue around gender, sexuality, and identity in ways that the culture needs to be pressed forward.”

Though not everyone we spoke to agrees that it’s wise for American Theatre to rush into an embrace of what looks to them like a linguistic fad, and what for others raises more unresolved questions than it settles, enough of our respondents were positive about the change to tip the scales. Finally, the more I thought about it, the more it became clear that the inexorable logic of inclusion properly only goes one way, and that is ever wider; once you admit a new (if long overdue) definition or recognition, there is no going back.

As producer/manager Tiffany Vega put it to me, in a typical formulation:

I have decided to the use the term Latinx as much as possible. As I am learning more about inclusiveness I have realized that because the Spanish language only allows for feminine and masculine descriptions of people, it is leaving out a large section of our compadres that don’t identify with either gender. I cannot assume that just because a person may dress and look very feminine means that they are not gender-non-conforming…I decided a long time ago that I will no longer do or say things or make theatre that continues to harm and trigger people. Adopting Latinx into my lexicon gives me that ability to continue to be inclusive of all peoples, and in two languages at that!

Vega’s reference to “two languages” is salient, as one root of this argument is the very word Latino and the related category “Latin American.” If Hispanic has become dubious because it refers to language, not ethnicity, why is a word that seems to reference a dead European language (Latin) preferable? As Huerta explained to me, it derives from a colonialist impulse:

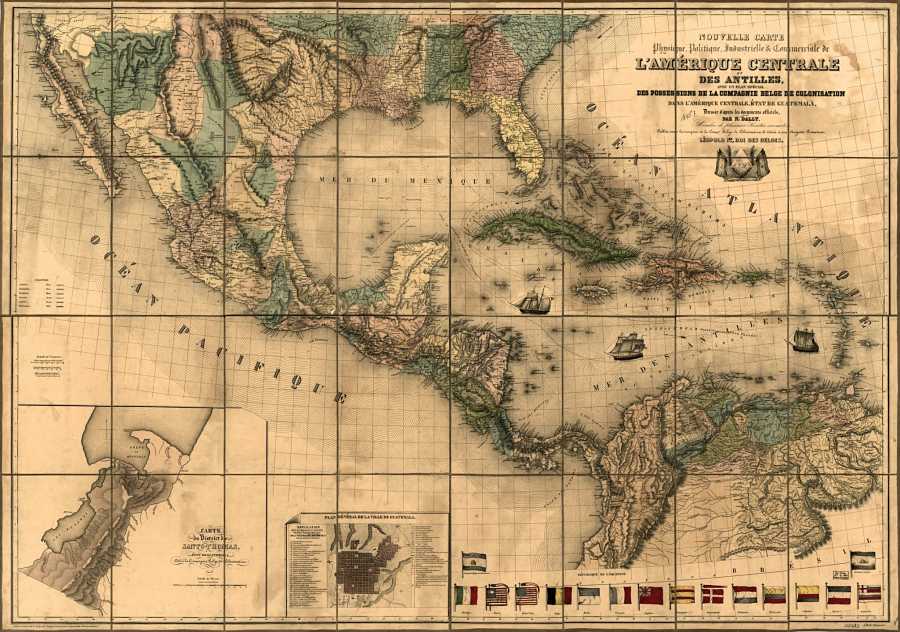

The very term, “Latin America,” translates from the French, Amérique Latíne, which was imposed by the French to define all of the cultures in their empire who spoke a Romance language, i.e., Spanish, French, or Portuguese. And “Cinco de Mayo” (a.k.a. “Drinko de Mayo”) celebrates a victorious battle in which the Mexicans defeated the French—so why not defeat the French terminology altogether?

One of the more compelling arguments I’ve heard against Latinx has been that it’s an inherently un-Spanish, Anglocentric solution to a problem that’s endemic to all Romance languages; to slap an “x” at the end of a Spanish word feels like a rude violation, a break with heritage. Are we now to refer to children as ninx? goes the logic of the objection. There are a few responses: Though it derives from Spanish, Latino is a word in English, and in particular in U.S. American usage; not only is English a promiscuous, carnivorous language, but usage in any language is a living, breathing thing, not a fixed quantity. Also: Spanish was not the indigenous language of the Americas*, to put it lightly, so to treat all its conventions as sacrosanct seems questionable at best. Finally, the imperialist roots of the term Latino itself should likewise leave it open to revision. As writer/director/performer Raquel Amalzan put it to me, “Latinx is a rejection of stereotypical representation and the limitations of the colonial past, and an attempt to move us into the future.”

Of course, a lot of the argument boils down to self-identification: What do people call themselves? Here it’s worth quoting Huerta at length:

The big question regarding self-identification for people of Mexican, Caribbean, Central, and Latin American descent born in or living in the U.S. has troubled folks for generations. Indeed, the question of identity has been around since the Europeans conquered the Americas. Further complicating the issue is the fact that we are not talking about one monolithic country of origin. In a word, it may come as a surprise to any non-Latina/o that Mexicans are not Puerto Ricans, are not Cubans, ad infinitum. So who or what are we? José Vasconcelos famously referred to the Mexican people as “La Raza Cosmica (“the Cosmic Race”), given the hybrid nature of the fusion of all races in Mexico and indeed the Americas: African, Asian, European, and indigenous roots. Ideally, then, the Mexican is Afro-Indo-Hispano-Asiatico-Europeo. But what do any of these distinctions reveal about a person?

I’m sorry for philosophizing here, but your question is vital and I am trying to be as inclusive as possible, and the historian keeps popping up in my head. It’s all about self-identification, period. And that means something totally different between groups and where they reside. Mexican-Americans began to use the term “Chicana or Chicano” in the 1960s as a form of rebellion; no longer living on the hyphen, as as it were. But traditionalists were appalled by this jargon—not a real Spanish term—and preferred Mexican-American or even Latin American…

Identification is always regional, as well. In Texas, many people prefer Tex-Mex; in New Mexico, many people consider themselves Spanish, as the descendents of the Spanish, Indian, Mestizo, and African colonizers who founded Santa Fe, New Mexico in 1612.

And I haven’t even begun to address what the Spanish-surnamed people of the Northeast and Southeast have called themselves all these years.

Huerta’s point about specificity is well taken. While we’ve chosen Latinx as our generic term for a more-or-less defined ethnic group, we are committed to as granular a specificity of usage as is possible given each instance in question. That means that you’ll still see Latina and Latino, even Hispanic, in these pages when they apply in their narrower senses (to Latinx men and women and Spanish-language literature, respectively). You’ll also not see us gratuitously edit people’s direct quotes or their organizational names (Latina/o Theatre Commons and Latino Theater Company, for instance).

One bit of usage that’s vexing: Latinx makes a poor noun; though we’ve certainly heard people try, “Latinx-es” doesn’t exactly roll off the tongue. What’s more, the indeterminacy of “x,” which can sound inclusive in an adjective, feels somehow inhuman in a noun (person = x?). So this new style is likely to force us to say things like “Latinx people” or “the Latinx community.”

As I noted, not all respondents were fully on board with us making this change, and I should account for their misgivings. Huerta was not the only one who joked that “Latinx” sounds like the name of a laxative (“Latinx—get all the shit out!” he quipped). Writer/director Guillermo Aviles-Rodriguez went further, voicing a common concern about inclusivity vs. specificity:

There is as of yet no word, term, or phrase that completely and perfectly articulates the mass of people who will likely be discussed in your issue. All the words (including “Latina/o” and “Latinx”) that I have heard to try and identify the groups in question as a monolith bring with them deficiencies. To solve this and for clarity, I take my cue from the artist or group I am describing. For example, CTG has commissioned me to write an educational guide for Zoot Suit by Luis Valdez, it would be bizarre no matter what the field may say, to call Zoot Suit and its author anything but “Chicano.”

Like many respondents, even those favorably disposed to Latinx, Aviles-Rodriguez urged American Theatre to take a “wait and see” attitude toward new usages. Jacob Padron, producer and cocreator of the Sol Project, had this to say:

I’m not a huge fan of Latinx, I think maybe because it further alienates outsiders from our community—it feels exotic, and the number of people who have asked me what this new word means or how to say is now in the double digits. That said, I think the Latino community is trying to be inclusive and issues of gender/self-identification, as you know, are complex. So I get why this word has emerged. And why people are using it regularly.

I still tend to use Latina/o and don’t plan to change to Latinx, but that’s my personal preference. Anyone who knows me knows that I believe in inclusivity.

Others pointed out that the recent introduction of Latina/o was a big deal that shouldn’t be swept aside lightly. Writer and dramaturg Isaac Gomez:

The establishment of the collective Latina/o was a hard battle won for the inclusion of the feminine Latin identity as a way to equalize the language to include Latina women as part of the conversation when discussing a group of both men and women. I mean—think about it. In the Spanish language, there could be a room full of 50 Latinas and 1 Latino, and the word Latinos will still be used due to the masculine default. Why is that?

Still, Gomez concluded:

I firmly believe the “x” expands and broadens our definition of what it means to be a man, what it means to be a woman, what it means to be neither, or what it means to be both. Throughout the years, there has been (and unfortunately remains to be) a history of violence against trans*, gender-non-conforming, and gender-non-binary individuals in the Latinx community. Though the use of Latinx may not cease this kind of violence and erasure, it further solidifies the intersection of non-binary-gender identities and Latinidad. It is a truly revolutionary exchange.

Director Lisa Portes provided us with a helpful timeline, from her point of view, of how the nomenclature has evolved:

May, 2012: the Latina/o Theatre Commons forms. We make two significant choices about our name:

1. That it is “Latina/o”

2. The “a” is first in the order

2012-now: In print we go by “Latina/o Theatre Commons,” and once the title is introduced we go to the acronym “LTC.” Some people begin using Latin@ in emails, etc., but all official written communication uses “Latina/o.”

2015: Last year was the first year that “Latinx” came into wide use within the mainstream theatre community. The LTC has begun discussing adjusting our name accordingly, but it is a larger discussion that requires consensus. We intend to come to a decision at our convening in New York in December.

The issue at the heart of fully adopting the term “Latinx” is that there are many women within the Latina/o/x community that feel that the “a” was hard and only recently won. Others (both men, women and non-gender-identifying) feel that Latinx is inclusive of all genders.

Early 2016: The Chicago regional network, ALTA, formerly the “Alliance of Latino Theatre Artists” officially changed its name this year to the “Alliance of Latinx Theatre Artists.”

October 2016: In my own writing, I use “Latina/o/x.” In oral discourse I now say “Latinaox” and I pronounce it much like one would think, but with an emphasis on each of the two ending vowels.

That was extremely illuminating, as were these nuanced thoughts from Princeton scholar Brian Eugenio Herrera, who wrote in part:

Speaking only for myself, I do not see “new” terms or formulations as necessarily replacing prior ones. Instead, I embrace this constellation of terms as providing options for greater specificity and inclusivity…

In terms of respecting identity, I believe that to impose “Latinx” on everyone carries risks of presumption. For gay and trans Latinos—and perhaps others for whom claiming and affirming a masculine gender identity has often obliged a measure of personal risk, struggle, and triumph—it feels disrespectful to elide that hard-won gender identity with an ostensibly inclusive term. We can flip this for lesbian and trans Latinas as well. In short, Latinx seems more gender-inclusive but—if someone (even someone queer) wants to affirm a Latina or Latino identity—it can feel like yet another way in which one’s specific gender identity is being erased or disregarded.

It’s an excellent point, and one we took seriously in our consideration, though when we write about a hypothetical “someone” who “wants to affirm” a particular gender expression, we are equipped for that level of specificity. At issue is finding a larger, maximally inclusive term for the larger community. Herrera brought up another point that’s harder to answer but is also worth a second thought:

Additionally, I believe that Latinx is not only a term of identity but also one that suggests a political stance. In this way it reminds me of terms like Chicano (especially as used in the 1970s) and queer (at least in its early 1990s application). When the term Chicano came on the scene, to claim “Chicano” as an identity meant to say that one had a different politics than Mexican Americans. Likewise, when queer first came along, it was device to signal political solidarity across sexual orientations for those who wished to resist the assimilationist stances and “acceptance-seeking” stances of mainstream lesbian/gay political organizations. Latinx seems to me to be doing similar work—underscoring the politics of identity and demanding respect for the work that remains to be done around gender diversity and inclusivity. So it therefore strikes me as suspect to call an individual or organization or anything “Latinx” when it hasn’t clearly prioritized (or even engaged) in the political project that the term demands.

We’re going to keep that objection in mind going forward. But as an editor I had a few specific choices in creating a style preference to use for the larger group identity. It can be argued whether there should be a generic word at all for such a large and internally diverse group—and as I’ve said, we take to heart the competing claims for specificity and self-identification—but given that we’ve just created a whole themed issue about Latinx theatre, we felt the need for a single word to do this larger work. My three choices were:

- To stick with “Latino,” which in Spanish assumes an officially gender-neutral status, much as “he” allegedly does in English.

- Pick either “Latina/o” or “Latina/o/x,” which look to my editor’s eye a bit like “his/her” or “s/he”—in other words, typographical anathema (I’ve long embraced the gender-neutral “they” on grammatical grounds, and more recently for roughly the same reason we’re embracing Latinx).

- Latinx, which effectively moots the word’s gender.

We at American Theatre felt the arguments for each of these choices strongly, if not equally. We also heard very clearly the caution against jumping too eagerly on a linguistic flavor-of-the-month. But after much reflection, it’s our feeling that we can’t afford to simply wait and see; the case for a new word is strong on linguistic merits, and in social-justice terms, it’s even stronger: Those whose gender identity has been erased by language have already “waited and seen” for far too long. We have need of words today that both honor our history and describe our current reality as best we understand it. So we’re not going to hesitate. We embrace Latinx now not merely as a compromise between a series of tough choices but, per Herrera’s last point, as a political stance. We are taking a side here.

We also recognize, in all humility, that we are late to this discussion, and that it builds on the work and struggle of many before us, and that it’s an ongoing one that won’t be settled by a single editorial decision. But we have joined the discussion, and joined it on the side of greater inclusion. The world only spins forward.

*This piece fails to mention another factor behind the “x”: Far from being a random character, some use it to invoke the indigenous languages of the Americas, particularly Nahautl. For more on this angle, see #3 here.