In May, Pegasus Theatre Chicago celebrated the 25th anniversary of Charles Johnson’s National Book Award-winning novel Middle Passage with readings of a new stage adaptation by David Barr III and Ilesa Duncan, retitled Rutherford’s Travels. The novel tells the story of Rutherford Calhoun, a freed slave from pre-Civil War New Orleans who unknowingly boards an illegal slave ship bound for Africa and witnesses the capture and enslavement of the (fictional) Allmuseri tribe of West Africa.

Johnson, a MacArthur Fellow and established cartoonist, essayist, screenwriter, novelist, and an educator for 33 years before his retirement, talked with me in the faculty lounge at Padelford Hall at the University of Washington about the readings and about his long friendship with August Wilson (the subject of another Q&A). Pegasus’s full production of the play runs Nov. 2-Dec. 4.

Knowing the material as you do, what was it like to see a stage version of your novel?

It was a very intense experience. The staged reading went for three hours, and I saw it two nights in a row. It would be less time, because they were reading the stage directions—that would not be in the final play. But they have every important scene in the novel onstage, and it was interesting to see how they inventively blended certain things together to get a sense of flow. There was an intermission. I thought it was very intense.

What particularly excited you about the stage adaptation?

I guess for every novelist or short story writer, what you are always curious about is how well the lines—the dialogue that you wrote and the action that you have described—can be transcribed to the stage. I was rather pleased to see how easy a transition it was.

You have worn many hats: critic, literary scholar, screenwriter, novelist. You also taught creative writing at University of Washington from 1976 to 2009. How has your career prepared you to sit back and enjoy your work when it is in the hands of others?

How has it prepared me? [Laughs.] Well, you know, I can sit back and I can enjoy it because this is their baby. I think it is really nice that they chose the title Rutherford’s Travels, because that was my working title for the novel for six years. I decided on Middle Passage when I got to the last chapter. I even published an early chapter or two under the title of Rutherford’s Travels in literary magazines. I had that title because I wanted to invoke, or have the feeling, the spirit, of Jonathan Swift; he has his Brobdingnagians, Lilliputians, and I’ve got the Allmuseri. In other works, I wanted that Swiftian feel to the novel. They did a smart thing with the title.

How did your friendship with August Wilson prepare you to see an adaptation of your novel?

Well, I saw August’s plays here in Seattle. I don’t get to see much theatre. That is something I wanted to improve on in my retirement, but I have not had the time. But I would always see August’s plays, so I got used to seeing really finely staged theatre, and I guess that interest carries over to seeing Pegasus Theatre’s production.

I am really surprised that Middle Passage has not been turned into a movie. Any talk about that?

We have been at three studios; I have written screenplays at two of those three studios, TriStar and Interscope. I did screenplays when the project was carried there by Hudlin brothers. Warrington Hudlin wanted to direct it at Tristar, and then Reginald Hudlin wanted to direct it at Interscope—we did a screenplay there that was fabulous, and it is the basis for a graphic novel that is partly done, illustrated by Dennis Cohen. The third studio, was Warner Brothers, where John Singleton wanted to do it, but he did not make that much progress.

Since you are the original creator of all the characters in Middle Passage, did you offer notes to the adaptors, David Barr III and Ilesa Duncan?

Nope.

You are an advocate of philosophy in your literature. Do you think the philosophical aspects of your work came through in the stage version of Rutherford’s Travels?

Some of it, particularly a speech that Captain Falcon gives where he talks about how the mind was made for murder—a very important line in the novel. All of the philosophy is not necessarily there, but enough of it is there. You see, one of the things about Middle Passage that I think makes it work as a story are the ideas embodied in the action. They don’t come at you just through the dialogue—the ideas are embodied in concrete things, like the ship and the sea. The sea is the Buddhist void. The ship, the Republic, is this republic that we live in. The book is heavy on metaphor, and the various real concrete things in it actually body forth the ideas.

Two writers that you had a great deal of respect for were John Gardner, a novelist, and August Wilson, a playwright. If they were with us now, what do you think they would say to you about Middle Passage being turned into a play?

I think they would say that they are glad to see it happen—I have no idea what they would say beyond that.

I know that if I ask you where would like to see Rutherford’s Travels onstage, you would say you would like to see it on stage in Seattle, since you live there. So instead I’ll ask, since I’m from New York City, will we see a production of Rutherford’s Travels there?

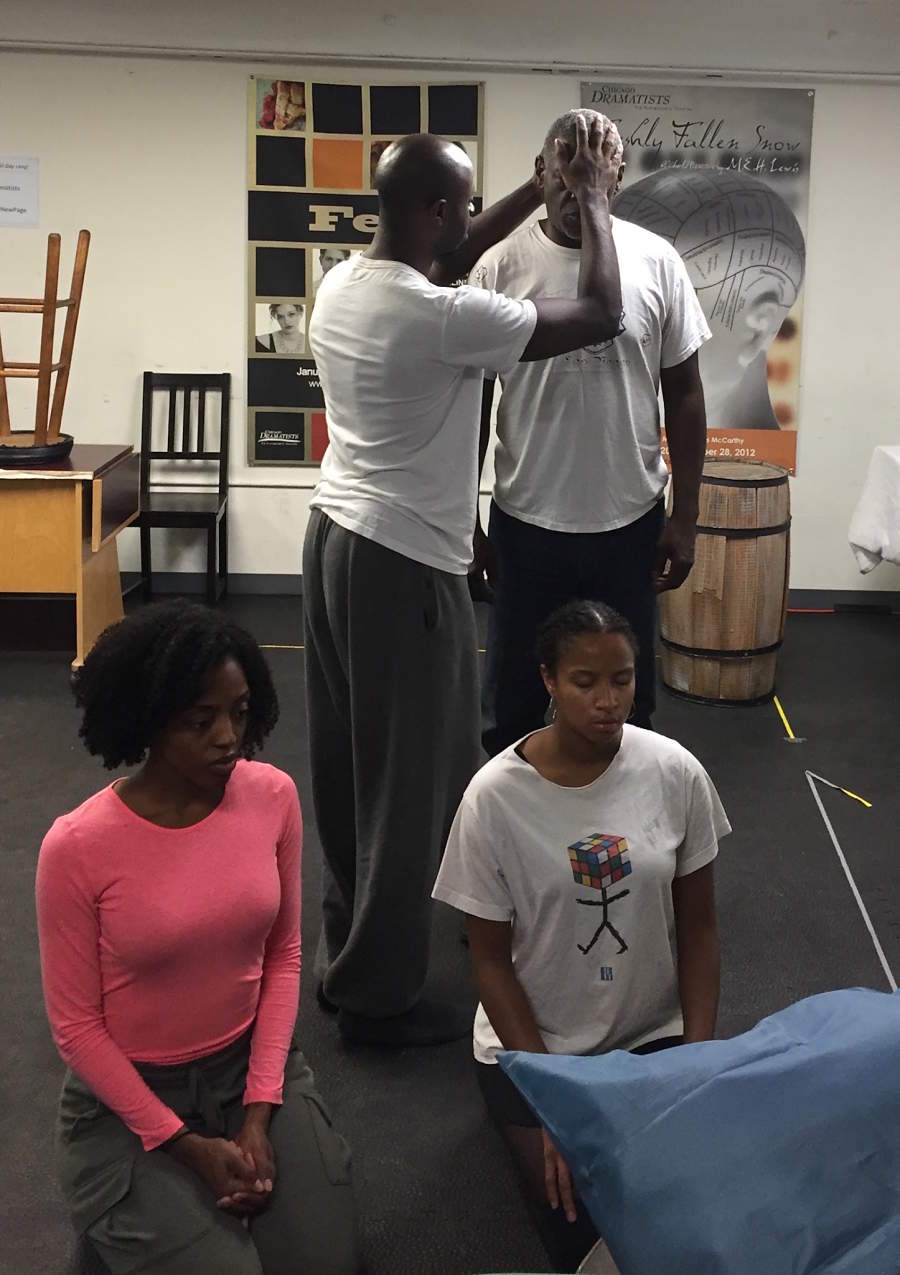

I would like to see it travel to different places. From what I saw—again, it was a staged reading, the actors were not in costumes, we did not have a set—when you have those things in November, the set for the ship and the actors in costumes, I think you will have a visually very powerful play that won’t be boring. It will be entertaining, and even riveting, in certain parts of the play. It will be worth going to the Rep here in Seattle or in New York. I wish them the best.