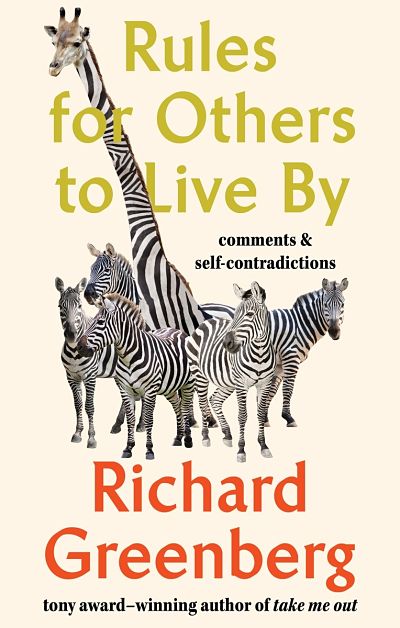

Richard Greenberg, one of the most produced playwrights of his generation, tries his hand at narrative nonfiction in an uneven new collection of anecdotes and essays, Rules for Others to Live By: Comments and Self-Contradictions. Not a tell-all or a primer on life in the theatre, nor a scandalous confession of addiction or abuse, the book instead depicts Greenberg’s life as a self-identified urban recluse. “I used to have a wildly exaggerated reputation for being a hermit,” he writes. “I still have the reputation, but it’s no longer so exaggerated.”

The book eschews chronology, and sometimes context, so when diving in it helps to already know the broad outlines of the 58-year-old playwright’s life: his education at Princeton and Yale; his coterie of friends and collaborators, most of whom get pseudonyms here; his health problems, including bronchitis, insomnia, and Hodgkin’s; his greatest hits, including Eastern Standard, Take Me Out, Three Days of Rain, and The Assembled Parties, and his flops, like A Naked Girl on the Appian Way.

The entries are mostly short—typically a page or two—and the gems are many. Greenberg is generally tough on humankind but can be unexpectedly empathetic, and many of his reflections on the city, on theatremaking, and on friendship in middle age resound with wisdom. “Very smart people’s opinions of art products should be taken with a grain of salt,” he writes at one point. “Often they believe that because a play or poem or novel has sprung fascinating thoughts in them, it is itself of high value. It isn’t. They’re just interesting people.”

Often his vocabulary is delightful; often his asides are wonderfully wry; often his character descriptions are vigorously animated. Take, for example, his hyper-professional friend Emma: “She didn’t fear poverty or illness or bad neighborhoods. What terrified her was the possibility of making a mistake. She saw error as a dissolvent; think Margaret Hamilton in The Wizard of Oz.”

Or, his “short, rotund, garrulous, friendly, neurotic, tacitly gay” high school friend Davey Prather, whose sisters were “soubrettes who tossed their hair and giggled and ate fruit in a lubricious manner.”

But despite his many gifts, Greenberg’s entry into the genre of narrative nonfiction is an uneasy one. The sometimes thorny ethics of memoir he addresses in a preface titled “Apology to Oprah,” a section which begins, “Everything in this book is true,” and ends, “This book is a work of fiction.” He acknowledges that he has changed some names and some locations, that a few of his characters “do not, in the strictest sense of the word, exist,” and that one or two of their stories may not have happened. Like Beyoncé with Lemonade, he’s going to let his fans wonder who’s who and how much of the book is exactly true.

And yet, with “Apology,” he’s at least offered an honest accounting of his dishonesty. To some readers this decision to occasionally fictionalize for the sake of privacy (his own and others), or for narrative cohesion, humor, enlightenment, or entertainment might seem like he’s copping out to the demands and consequences of nonfiction. Others will cut him some slack—I did—and recognize this is a work of art, not journalism, and he isn’t pretending otherwise.

As a playwright, Greenberg has been lauded for his command of structure, for creating alluring worlds where every character is fully rounded and every detail is essential. This collection of essays, which runs over 300 pages long, does not feel as rigorously assembled. A good quarter of the entries seem hastily drawn and do not make a case for their own inclusion. Often Greenberg starts on an interesting topic—rich people, or selling out, for example—and abandons it a few paragraphs later. The overall logic of the essays’ arrangement is elusive: Although the book is organized in themed sub-headings, sometimes these sub-headings achieve little (like “Things Are Looking Up, Maybe; and Back”), and the order of the essays does little to make the collection feel like more than the sum of its parts. The result is ultimately more like a yard sale experience, as if an editor pulled everything Greenberg was ready to dispense with onto the lawn for readers to sort through.

Of course, an inherent challenge—and freedom—in publishing a collection of stories and essays is its untethered-ness to a unified narrative. Other recent essay collections by theatre artists embrace this challenge and turn it into a strength. In 100 Essays I Don’t Have Time to Write, Sarah Ruhl combines memories of early motherhood with thoughts on making theatre. In Intimacy Idiot, Isaac Oliver shares a series of laugh-out-loud observations on dating, riding the subway, and working in a box office. Both authors seemed free to abandon narrative, to make wild turns, to uncover what might be off topic or inessential, to change form or tone, and yet their books had a quality lacking in Greenberg’s: They felt urgently propelled by a genuine internal investigation. This quality produced a kind of trust that made me never question whose hands I was in, or whether the author had taken enough time with each essay, or if the stories were in the most effective order.

The most irritating of the underdeveloped bits in Rules are Mr. Greenberg’s various references to racism. In an early essay, “Selves,” he describes his extreme discomfort walking among the masses in Midtown. “This is where it would be helpful to have the skills of a good racist,” he writes. “Racism, historically, has been both a psychosis and a labor rationale, but more broadly, I think, it’s been a convenience. There is simply too much assaulting us, more to care about that we can possibly cope with. How better to deal with this than to lop off whole populations from the arena of public concern?”

Putting aside that there are so many ways to move through midtown Manhattan without going bananas, why would Mr. Greenberg want to write about racism in such a glib, reductive way? What appears intended to feel arch, urbane, and postracial instead comes across blithe and out of touch—byproducts, sometimes, of excessive privilege and solitude.

Later in the collection, in an essay titled, “My Racial Incident,” a black woman working the cash register at his neighborhood Rite Aid shortchanges him by five cents. When he returns to the counter to get his money back and hovers there, he interrupts another 40-year-old black woman being rung up. The cashier gives him a “slightly affronted, frankly questioning look” before giving him his nickel and telling him, “For the next time, you should know you’re being very rude to the other customer.”

“This threw me,” he writes. He apologizes to the women, tries to explain his justification, receives “a look of scorn and incredulity,” and apologizes again. He speculates that the woman being rung up is “tired of being asked to absolve white people.” He then steams that no one apologizes to him. “Here is the situation as I see it: I was shortchanged; I behaved properly; I did all of the apologizing.”

The lack of self-awareness here is baffling, as is the lack of empathy. Who, as he is writing, does he imagine is sympathetic to his plight in this story? And what’s he really getting at here? What’s so important about that nickel, about the power dynamics, or about the racial components of the story? He says that to have let the five cents go would have been “too dweebishly liberal”—is that what he fears becoming in life? How would he have wanted a woman working a counter to speak to him when he’s being disruptive and discourteous, and in denial of being so? What’s more, elsewhere in Rules, Greenberg gives elaborate descriptions of female characters; yet he does not describe the appearance of either of the women at the counter, the main characters in this story, beyond the color of their skin—why not?

In a subsequent section titled “On Liking Racist Things,” he begins with an affectionate description of a genteel white friend who confesses she has become romantically obsessed with videos of Al Jolson singing in blackface. He reassures her that her predilection isn’t evidence of racism or any other kind of character flaw and announces (to the reader) that he’s going to list the racist books, musicals, and TV shows that he likes. Swift, quippy entries follow about Rodgers and Hammerstein, Ernest Hemingway, Agatha Christie, and others, ending with “The Golden Girls,” an odd choice he explains thus: “Cunningly, the ethnicity being disparaged was Minnesotans, so it was possible to have all of the fun of racism with none of the blowback.”

Was I supposed to chuckle? Moments like these felt meant to be read in a certain context: white, liberal, urbane. It’s the kind of context that often permeates the American theatre. When I read this section, I happened to be on a tour of Alabama, seeing historical sites of decidedly un-fun things like slavery, police brutality, voter suppression, segregation, church bombings, lynchings. The casual and uncritical citations of racism in Rules could not survive this context. Is Greenberg trying to establish that he and his un-dweebishly liberal friends are above racism, beyond it? The end result does not feel amiably astute but grimly blind and deaf.

What emerges across the collection is that the solitary writer’s life that Greenberg has built for himself in the city is sometimes charmed and sometimes poisonous, sometimes responsible for protecting his sensitivity and observational prowess and sometimes responsible for blunting them. Near the end of Rules, Greenberg recalls the wedding of a close friends:

Even in the thick of situations, and very happy about it, I don’t generally feel a part of things. I have lots of friends and acquaintances who count on me to lend a sympathetic ear and give good counsel, but when I bother having a picture of myself, it resembles, funnily enough, the inaccurate picture I used to have of the New York City traffic tsar Janette Sadik-Khan—someone alone in a room, studying the computer simulation of the real world and, based on those researches, issuing commands as to how the traffic should flow. As much as I’d enjoyed the party—as I enjoy most parties—in the cab after, I felt, as always, that I was heading back to freedom.

It’s a clear, poetic, and complicated picture, embracing of vulnerability and toughness, humor and sadness, hopefulness and hopelessness. It’s one of many moments that kept me happy to return to the book and its requisite parsing through of dross and gold. For all its missteps, Rules finally got under my skin and redeemed itself, again and again.