Relations between the United States and Russia have lately been a bit, shall we say, tense. And the strain apparently extends beyond political leaders, as the State Department and United States Embassy in Russia found out from a recent survey; when Russians were asked what they liked about Americans, they answered, in essence, “Not much.” But when asked what Americans do well, oddly, one of the top answers was “musicals.” (Russians obviously missed Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark.)

So America’s diplomats looked stageward for help and discovered Broadway Dreams, a decade-old nonprofit that runs week-long master-class programs throughout the United States and internationally, taught by actors, directors, choreographers and others with Broadway experience. In April, Broadway Dreams made history when the State Department and U.S. Embassy sponsored a 10-day trip to Moscow to work with Russians on musicals and, in the process, hopefully break down barriers between the two countries. There were workshops, two public panels on theatre, a private concert for diplomats and others at the residence of the U.S. Ambassador to Russia, and two mainstage performances featuring scenes from such shows as West Side Story, Cabaret, and Hairspray. These marked the first time professional American and Russian actors performed together in a Moscow theatre.

How did it go?

“We started a discussion,” said Annette Tanner, Broadway Dreams cofounder and president. “I think we improved the way Russians view Americans. When you come together to work like we did, you realize we all want same things and all have same dreams.”

Balint Varga, the group’s musical director for the trip, hails from Hungary and speaks some Russian. He said the felt this kind of exchange is “perfect” for improving relations between the countries. “Culture is neutral territory—people don’t care where you come from, they just want to share the art.”

Broadway Dreams Foundation was born in 2006, evolving out of for-profit theatre classes started by Tanner and three friends. “Seeing the students and faculty learning from each other, I realized that this education should be about talent, not just who could afford it,” said Tanner, a New Zealander, who tries to provide scholarships for anyone who needs them (last year, 42 percentof all students received full or partial scholarships). Most who sign up are aspiring actors at the start of their career, and many have landed professional acting roles in New York or on national tours afterward; students have ranged in age from 7 to 67. Primarily, Tanner said, “We are teaching arts education and life skills.”

The intensive master class program started with just actors as teachers, until Tanner realized she needed choreographers to create moves for the performers, and then that she needed directors on board as well. Later she began working with composers, so there are now also new shows in development being workshopped at the weekly programs and industry showcases. “This year we have workshops in New York and Atlanta and fully produced shows in Toronto and Philadelphia and Los Angeles and outdoor concerts at other classes,” Tanner said.

It was while she was leading a workshop in New York last year that she got a call from the State Department. She initially thought they were requesting a program for Washington, D.C., until they mentioned a different time zone. “Then I said, ‘Wait, where are you talking about sending us?’”

Tanner said she initially thought the plan was to teach theatre to college students there. Then she found out they’d also be working with professionals, including the casts of current Russian productions of Phantom of the Opera and Singin’ in the Rain. She soon learned that despite Russia’s long and storied cultural history—Moscow Art Theatre, Bolshoi Ballet, et al.—Broadway-style musicals are “a new part of the culture there,” she said. Indeed, it was only in 2002 that English-language musicals began appearing there. The first, 42nd Street, had its run cut short when audiences shied away from theatregoing in general after Chechen terrorists held a whole theatre hostage during a Russian musical called Nord-Orst (about 170 people died during that crisis).

Still, slowly but surely musicals have grown in popularity in Russia, and maybe because most, including Phantom and Singin’, are performed in Russian (actually, some have Russian dialogue while the songs remain in English). “The quality of the productions is exceptional, and they play to huge houses with 4,000 people,” she said. She realized that collaborating on this level “was an incredible, historical opportunity.”

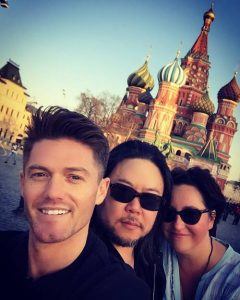

The team Tanner put together included Varga, the musical director, along with directors Stafford Arima and Dan Knechtges, choreographer Spencer Liff, and performers Ryann Redmond, Quentin Earl Darrington, Matthew Scott, and Tyler Hanes.

While there was concern about pulling off such a cross-cultural project, given the logistics, political tensions, language barriers and the societal differences, Arima (Altar Boyz, Allegiance) said he was “not at all surprised it came to fruition. Annette has an enthusiastic vigor and an infectious desire to reach as many people as possible.”

For her part, Tanner said, “Everyone was skeptical about it actually happening right up to the week before I left. People were also worried there’d be no tech support or no translators or just cultural issues where they would say yes to everything even when they didn’t mean it.”

Others fretted about their hotel rooms being bugged or about being tailed by Russian intelligence, or worse. On the second day in Moscow, someone from her team asked Tanner, “How do we get to the embassy from here, just in case we need to make a run for it?”

These fears proved unfounded, as everything went well and the team even enjoyed their time away from work there, going to the theatre, ballet, and opera. “There was better coffee and cocktails then I expected, and it was so much cheaper too,” Tanner said, adding that while traffic could be “horrendous—it was always either stopped or moving like the Autobahn,” the Moscow Metro was fast, efficient, and beautifully adorned with mosiacs and other art. And, of course, as in the U.S., there was always Uber.

Broadway Dreams spent the first two days in Russia auditioning 400 actors for 70-80 slots, including the stars from Phantom and Singing in the Rain. Tanner said there was so much talent they ended up with a total of 103 performers.

“They are behind in terms of musicals, but they are open to the Broadway culture,” Varga said. “Many of them had the skills but just had had different training.”

Broadway Dreams worked with the performers on selections from Hairspray and Cabaret, which was performed in English, and West Side Story, in which Tony spoke English and Maria spoke Russian; they also worked on Annie with a children’s theatre, and Arima directed an excerpt of Nord Orst as a tribute to those who died and survived the siege of the Dubrovka Theatre. The shows were well received, including a performance for 350 VIPs at the ambassador’s residence, which ended with “everybody singing along in kind of a karaoke,” Varga said. “It was so cool to see everyone forget about their problems. Sharing that was the best night ever.”

There was plenty of learning on both sides along the way, as ingrained misperceptions were undone by reality. Tanner said that some Russians told her they “grew up thinking Americans are not very smart, and when they travel they are loud, obnoxious, and entitled,” but that the Americans they met in this exchange defied that expectation.

For his part, Arima said that as a director he went in striving “to understand and learn from them” as much as he was trying to direct them. “We were coming into their home as guests,” he says. “We’re not coming just to teach you ‘the way it should be done,’ because that would fulfill a certain stereotype and be counterproductive diplomatically.”

There were definite cultural differences. During a number from Ragtime, Arima was encouraging the actor to provide more of a “rebel cry, like when you want to protest something”—a quintessentially Western attitude that reportedly drew blank stares from performers raised in Soviet era and now Putin-run Russia.

Still, Arima was inspired by the actors’ desire to connect—they liked “how Americans are more open to discussing things and having a communal experience”—and impressed by their commitment to the text. “They always wanted to understand the motivation behind the lyric or the moment,” he said. “If I said, ‘Come down and be more centerstage,’ they’d want to know why—that often superseded worrying about the notes they were singing. That to me was beautiful.”

Eventually the performers from the two countries began having more casual conversations late at night about their countries and their differences. “Experiencing each other in the flesh and blood and not in stories was important,” Arima said.

Tanner said she’s in preliminary talks for a return trip and maybe even a second program in Siberia: “We are also discussing the idea of a full concert of Chess with a half-Russian, half-American cast that would be performed in New York and Moscow, possibly at the Kremlin.”

No one’s under any illusion that these performances will bring about world peace, or even soothe the renewed tensions in our post-Cold War world. Dmitry Bogachev, managing director of Stage Entertainment Russia, Broadway Dreams’s Russian partner, raved about “the unique experience of American and Russian cast and crew working together side by side on one stage selflessly and passionately,” calling it “an amazing demonstration of how theatre unites people and countries better than any politicians.”

For her part, Tanner said she’s all in. “Especially in a climate of such division, I think if we can continue to take small steps and bring people together we are really doing something amazing.”

Stuart Miller is a freelance journalist based in New York City.