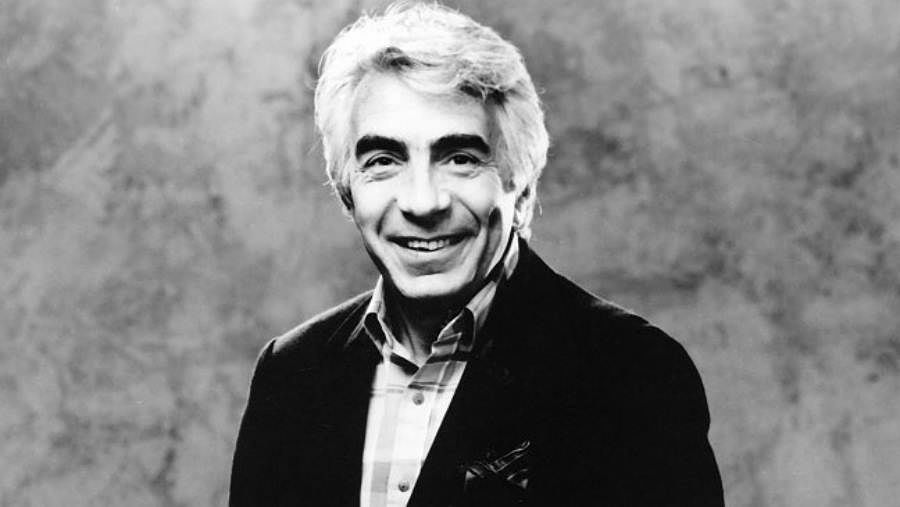

On Sunday, October 2, Gordon Davidson, the founding artistic director of Center Theatre Group in Los Angeles, collapsed and died unexpectedly at a Rosh Hashanah family dinner. For those of us who knew him, it was a shock. Gordon was just 83.

I say “just” with intent. If you knew Gordon you expected that he would live forever (which, in a way, he will). Dan Sullivan, my colleague, best friend, and best boss for 18 years in the theatre department at the Los Angeles Times, put it this way: “Why a shock at 83? Because [Gordon] always seemed so young and receptive.”

And what he seemed was what he was. There were no surprises. Gordon, the son of a respected professor of theatre at Brooklyn College, embraced theatre seriously when became the stage manager for the Theater Group at UCLA. Led by John Houseman, the Group was intended to take up residence at the Music Center once the 750-seat theatre, the drum-like Taper, was completed. Houseman’s personal recommendation anointed Gordon as its founding artistic director.

One of Gordon’s most distinctive traits was a kind of naïveté that sometimes got him into trouble—such as scheduling a production of The Devils, a dark John Whiting play about sex and demonic possession in the church of 17th-century France, based on Aldous Huxley’s The Devils of Loudun. It was his choice as the inaugural offering at the brand new Mark Taper Forum, despite rumblings from the hierarchy of the local Catholic church. Everyone who was anyone in Los Angeles attended the opening, including Gov. and Mrs. Ronald Reagan, who went scurrying away, along with appalled board members, after Act One. Gordon’s career threatened to be over before it ever began.

Fortunately he had the support of smart people in positions that mattered. He not only survived the crisis, but went on to run the Taper by always listening to his own instincts. His 38 years in that job—1967 to 2005—were an uncommonly long time. He was not immune to the toll of that longevity, but the scope of his achievement (prior to his less defining later work) changed the face of Los Angeles theatre forever.

It was my good fortune to be in on what would prove to be Gordon’s best years. I remember that whoosh of fresh air known as New Theatre for Now (NTFN), an inspired mini-festival of experimental work such as Los Angeles had never experienced before. With the capable Ed Parone at his side, Gordon treated a famished L.A. public to a banquet of new playwrights, actors, designers, and directors. If NTFN’s large demands eventually killed it, the flow of fresh talent in all aspects of production did not vanish. It became the hallmark of the Taper.

After his initial stumble with The Devils, Gordon grew savvier but never drifted far from plays that spoke to him socially, politically, humanely —plays that displayed exuberance, conviction, muscular writing, wit, and imagination.

He introduced L.A. to the anti-establishment work of Václav Havel and Athol Fugard. There was also Brecht’s Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui, In the Matter of J. Robert Oppenheimer, Murderous Angels, and The Dream on Monkey Mountain. Fugitive priest Daniel Berrigan’s antiwar Trial of the Catonsville Nine brought rumors on opening night that the FBI was in the house hoping to nab the author (which the author wasn’t, and they didn’t).

Gordon championed Anna Deavere Smith’s one-woman social studies, none more than Twilight: Los Angeles, her piece about Rodney King and the L.A. riots, because it confirmed his belief that theatre works best when its concerns are anchored in community. He embraced Luis Valdez and the stunning rise of Latino theatre in California by giving Valdez and his Teatro Campesino the opportunity to go mainstream with Zoot Suit at the Taper. If the production was met by blank stares when it transferred to New York, Valdez knew why. “New York is too far to go for a plate of menudo,” he said. (A revival already scheduled for early next year at the Taper may become a fitting memorial to the man who made it possible the first time.)

Over the years the term “a Taper play” became part of our vernacular. It was shorthand for something meaty, committed, liberally inclined. After Gordon staged Michael Cristofer’s The Shadow Box (about cancer) and Mark Medoff’s Children of a Lesser God (about deafness) and both transferred to New York, Joe Papp scoffed, “I don’t do disease-of-the-month plays.” But Oskar Eustis, a man mentored by Gordon and Papp’s successor at New York’s Public Theater, suggests that Gordon saw theatre as a place “not to just reflect America but to expand our idea of America.” In 1977, Shadow Box earned Gordon a Tony for best director and the Taper one for outstanding regional theatre, while Cristofer nabbed a Pulitzer.

The Taper productions of Robert Schenkkan’s The Kentucky Cycle and Tony Kushner’s Angels in America remain for me the most vivid. One could argue that both were conceived and partly developed elsewhere, which is true; but one of Gordon’s other great gifts was to spot the work that deserved major development or exposure and provide it.

Clearly his achievements were many and significant, but they are not the main reason he leaves behind an indelible impression. What we miss when we miss Gordon is his transparency, his grace, his affability, and—to use a word that has fallen into odd disfavor—his sincerity.

His gift for schmoozing never descended into small talk. He could be naïve and was not immune to making bad choices now and then (who is?). But he was never a schemer—never duplicitous. Valdez aptly called him “supportive but not intrusive.” Modest by nature, Gordon gave credit where it was due, took chances he believed in, and seemed unaware of the life-changing nature of what he was doing. It was as natural to him as breathing out and breathing in.

Once, nonplussed by a string of unfavorable reviews the L.A. Times had sent his way, he invited Dan Sullivan and me to lunch. He wanted to talk. We were candid. Gordon was not angry; he was hurt. To this day I’m not sure he believed what we had to say. How could we not have liked what we saw after all the hard work that had gone into creating it?

You cannot resist someone who is hurt rather than angry. As we left Dan told me that in the interest of separating the critic from the criticized, he would agree to get together with Gordon only once a year and only for breakfast, “because Gordon is so seductive.”

I related this in a longer piece I wrote for the tribute-filled program of the gala hosted by the Music Center in December 2004, honoring Gordon’s achievement and retirement. Here’s what else I wrote:

During my reviewing days, Gordon had a habit of stopping by my seat to say hello. It was never unctuous. It was just something he did…I appreciated it. If once in a while he felt compelled to throw in word of explanation about the play I was about to see—well, it was meant to be helpful, it was not meant to tell me how to do my job.

When I began to ask for front row seats in the mezzanine at the James A. Doolittle Theatre in Hollywood [now the Montalban] because, at five-foot-one, I had trouble with sightlines in the orchestra, he was profoundly concerned. He feared I would not see the play as well from up there as from some more traditional spot downstairs. I’m not sure that I ever convinced him otherwise. It was all part of an inescapable Davidson DNA that was impossible to interpret as meddling or, heaven forbid, unwelcome. It was just Gordon being Gordon or a Taper play being a Taper play. Los Angeles was lucky to get its [38] years of undivided attention before the man with the perpetual spring in his walk and the shock of dark-hair-turned-white decided to move on.

This time for good. But what a legacy he left behind.

Sylvie Drake is a translator, writer, and former theatre critic and columnist for the Los Angeles Times.