Twenty feet in the air, suspended by cords, an Angel slowly flaps her great wings inside a dark, billowing, parachute-like heaven. Onto its rippling surface is projected an image of Marc Chagall’s painting Garden of Eden.

The angel, played by Jeremy Louise Eaton, performs a deceptively simple dance: She is birthing something already dead now for 13 years. The heavens shake with an undulating pang as the angel flies out over the dark world below. Light separates the earth from darkness, and the 20th century is born. The great curtain on the world is opened and the gaiety of an early-20th-century village momentarily holds at bay the depth of the tragedies to come.

Double Edge Theatre’s Chagall-inspired new work, The Grand Parade, premiered in February at Arena Stage’s Kogod Cradle, a state-of-the-art 212-seat venue that is part of Arena’s recently transformed complex, the Mead Center for American Theatre, in Washington, D.C. The textless performance finds its theatrical style in the Russian artist’s kaleidoscopic vision of humanity at play, at war and at rest. Trapeze, circus, dance, projections and images from popular culture fill the height and breadth of the stage. Populated by people and animals in acts of grace and destruction, The Grand Parade depicts the history of the 20th century with a wealth of iconic sounds and images from film, television and photography.

Chagall’s Jewish experience fleeing Nazi Europe is not only on the minds of members of Double Edge, which is based in rural western Massachusetts. Simultaneous with The Grand Parade’s D.C. debut, an exhibition at Musée de Luxembourg in Paris portrays Chagall as a historian of the 20th century because of his proliferating images of the Russian Revolution, soldiers, war and Jewish persecution, juxtaposed with Judeo-Christian iconography.

Presenting Double Edge’s devised work at Arena is a new move for this venerable D.C. institution, but well suited to its remodeled home and to the sensibilities of artistic director Molly Smith. “Three summers ago, I saw Firebird, a work also inspired by Chagall, up at their farm in Ashfield, and it reminded me of the company-created work I saw in Europe in the late 1960s and ’70s,” Smith told me. “It was visual, emotional and environmental.” During that visit, Double Edge founder and artistic director Stacy Klein spoke to Smith about a new work she was thinking about, and Smith was intrigued. “I was captured by the boldness of the vision—to encapsulate every decade of the 20th century in music, movement, dance and aerial work. This was a century about flying. I like the strong focus on wars and revolutions, seen lightly through the eyes of Chagall.” The following summer, Smith formally invited Double Edge to premiere The Grand Parade in the new Kogod, and a period of two years of development at Double Edge’s 105-acre farm began.

Smith was right about Double Edge’s aesthetic roots. Klein studied in Poland with members of Jerzy Grotowski’s Polish Laboratory Theatre in the summers of 1976 and ’77; an especially important influence was Rena Mirecka, who, along with Zygmunt Molik, came as a guest artist to Double Edge in 1985. (Mirecka continues to teach at Double Edge, with her most recent residency in the summer of 2012.) Double Edge is an international company, whose members hail from the U.K., Argentina, Bulgaria and the U.S. What could be more American than this rich diversity of origins?

In making The Grand Parade—billed as a company-devised work with music by Alexander Bakshi—Double Edge began by researching American history and exploring what it would take to conjure the 20th century decade by decade; Klein led the process of selecting specific scenes and tracking emerging ideas. Because the 20th century still lives in generational memory, its scenes get played out somewhere between the physical stage and the stage of the spectators’ minds. Chagall’s recurring depictions of people and angels floating over and amidst the flow of history contributes to the work’s sense of an ultimate unknown, as do the piece’s “études,” short scenes that evoke both personal and national memories. The meaning is ours to discern.

The company engages in ongoing physical training, ranging from improvisation and voice work to plastiques, yoga, trapeze and work with large objects such as giant wooden spools, gym wheels and teeter-totters. Their theatrical skills go on brilliant display in large-scale open-air summer performances that utilize Double Edge’s farm environment as well as the upstairs loft of a barn rigged for theatre, and serve as the basis for classes at the farm and elsewhere. The tour of The Grand Parade—which the company will keep in its repertoire for the next five years—is supported by a $125,000 grant from the New England Foundation for the Arts. It played in March at the Golden Mask Festival in Moscow with additional support from the Trust for Mutual Understanding.

Inspired by Chagall’s reverie of life with a tragic core, The Grand Parade is a work about our experience of history rather than history itself. Sergei Eisenstein’s 1923 idea of “a montage of attractions,” so central to film, aptly describes The Grand Parade’s rush of events, personages, dance styles and images including urbanization, radio, World War I, ragtime, Stanford White, Houdini, the Keystone Kops, revolutions, the automobile, the Charleston, Amelia Earhart, the Roaring Twenties, the Great Depression, telephones, World War II, the Rosenbergs, television, nuclear proliferation, the twist, the Kent State murders, Martin Luther King, John F. Kennedy, computers, the Berlin Wall, Malcolm X, Bobby Kennedy, disco, the Internet and dial-up modems. In this mix, the individual is anonymous and specific, iconic and personal, dream-like and actual.

Klein is an intuitive director. “You take a version of the past that may or may not have happened, just as prayer creates a vision of a future that is desired,” she posits. “We grow up with refracted memory, with cultural and familial memories. For many there is a sense of being innocent observers. Our research was driven by identifying recurring patterns of history. The rehearsal material we selected was more metaphoric than rational. We looked for things that were both real and dense with meaning; things that represent our world and something beyond it. Our research allows actors to create deep personal associations that are tied to a real past and a possible future.”

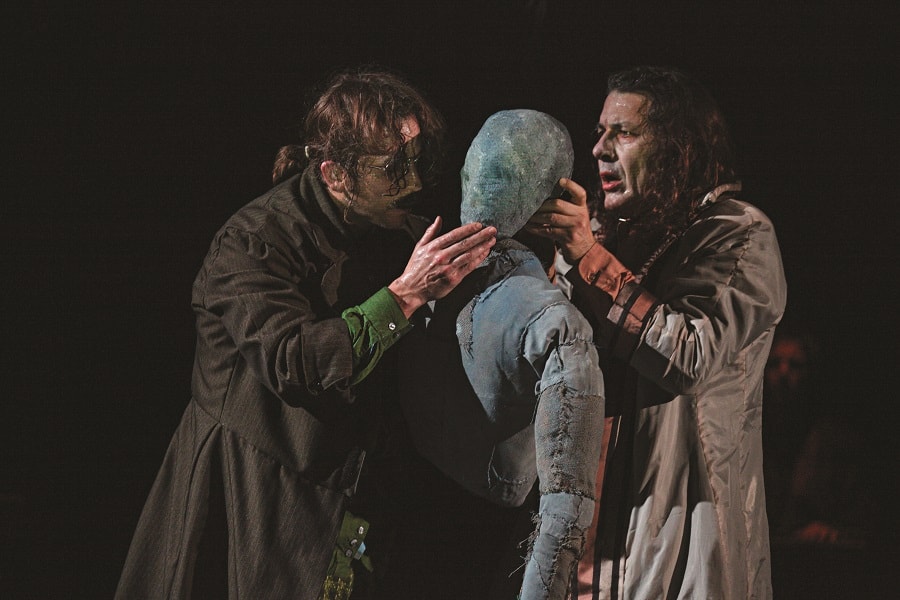

Our memory and understanding of the past century, as Double Edge portrays it, are connected to trauma, exhilaration and exhaustion. The Grand Parade tells a story, but not through dialogue: No one speaks. The narrative of history is conveyed by documentary footage and images projected on a screen mounted behind a bar, a powerful mise-en-scene that connects image and movement with metaphor. In an extraordinary moment after the carnage of the world wars—on the battlefield, in bombed-out cities and amid the Holocaust—performers Matthew Glassman and Carlos Uriona sort through the dismembered dead looking for loved ones. They find a torso and a head that they slowly assemble into one human being. Glassman lovingly and tragically holds the remains until they slip from his grasp onto a deadly mound.

Civilization is put to the sword and then given an autopsy. The Grand Parade implicitly asks us to consider the past’s persistence in the present and its projection into the future. What are the terms of memory, and what is memory’s relationship to imagination? What is the path from the official narrative of history to subconscious memory and understanding?

At the center of the stage is a rather antique-looking 1980s treadmill that (beyond being a symbol for running without getting anywhere—is this history?) becomes alternately the means of conveying soldiers to the front, a bus and an escape route. When actor Adam Bright jumps on the treadmill with renewed vigor several times during the performance, the contraption becomes a metaphor for time itself, and how it speeds up as we grow older. Like memory, The Grand Parade is simultaneously transparent and opaque—transparent in what it presents, and opaque in the ultimate meaning of the events presented. Milena Dabova, for example, portrays Hitler’s chilling desire to conquer the world by crossing the stage with determined mincing steps, balanced atop a globe in the manner of Charlie Chaplin in The Great Dictator.

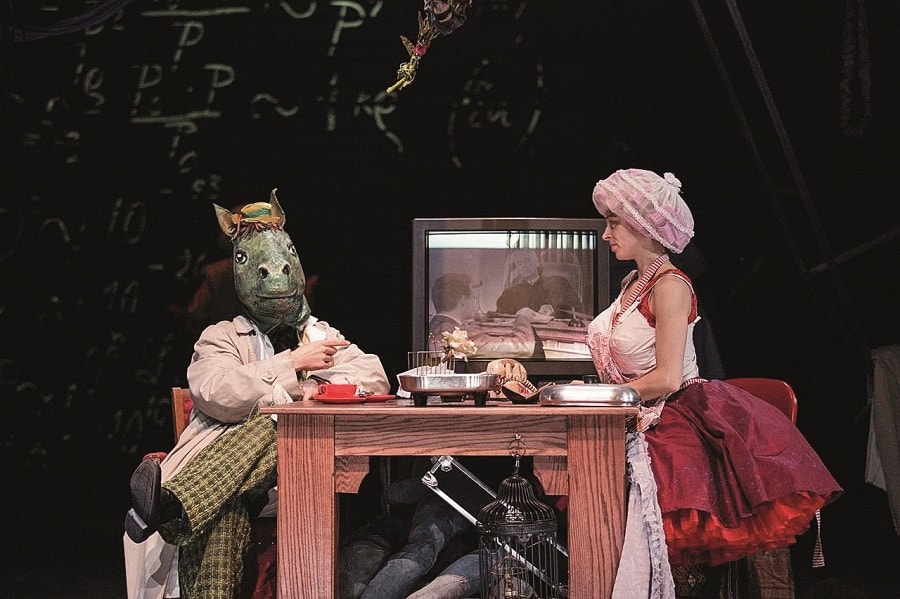

In addition to the tent-like parachute hung in the center of the stage, the bar and the treadmill, The Grand Parade’s set consists of a trapeze and large geometric shapes; there are period costumes as well as strange creatures that are half-human, half-rooster or half-horse. “Chagall has ways of seeing in terms of opposing realities,” Klein says. “These include color and multiple ways of telling a story. Chagall lived nearly 100 years. His vision embraces personal experience, mythology and history, all of which float above reality in his paintings.”

Several weeks before the premiere in D.C., Double Edge presented 12 workshop performances of The Grand Parade at the Baltimore Theatre Project, sponsored by the newly founded Baltimore Performance Kitchen. This allowed the company to complete the work in conversation with audiences—in this case (as John Barry reported in the Baltimore City Paper), a remarkably diverse mix of hipsters, kids, old folks and artists who eagerly participated in discussions about the making of the work. After Baltimore, Double Edge was in residence at Columbia College Chicago, thanks to faculty member Jeff Ginsberg. There they taught a movement-based theatremaking course for the college and a special training session for 18 Chicago theatre practitioners, performed two sold-out previews at the Dance Center, and participated in such ancillary events as a family dance workshop for 35 parents and their children.

As is typical, Arena also did targeted outreach related to the show. Double Edge members taught workshops for D.C. artists and students; the Phillips Collection hosted a conversation between curator Elsa Smithgall and Klein about Chagall’s aesthetic; talkbacks and post-performance panels followed the Arena showings. Arena literary manager Amrita Ramanan sees presenting Double Edge as “a great opportunity to engage with the imaginative aesthetics of storytelling—their rehearsal process has always involved a wide range of artists, from musicians, visual artists and landscape artists to scholars, producers and presenters, and even local restaurants and bakeries.”

For Smith, “bringing The Grand Parade to Arena helps open up our audiences to different ways of seeing theatre—work that does not have to be narrative in the sense of being driven by text. Younger audiences come from a visual world, one that is less literary and text-based—although I must say some of our older audiences are the most sophisticated, because they have seen and experienced all forms of theatre.”

In the last analysis, it is imagination that unites us through time and space. Early in her career, Klein saw Tadeusz Kantor’s The Dead Class (1975) in Krakow, a work that included mannequins as representatives of the masses and the dead. In The Grand Parade, mannequins hover on the edges of the stage—they are the dead and wounded of history standing silently at the periphery of our consciousness. Kantor, Jewish like Klein, told the group of students of which Klein was a part that they would probably never amount to anything “more than shit” unless they came to understand that life was more important than they were. This lesson Klein learned. At the end of The Grand Parade, we are returned to four live musicians, led by an evocation of Chagall’s indelible violinist, a lone figure playing in the Jewish ghetto, and an archetype for Fiddler on the Roof. It is as if he, like us, has survived it all and lives not only to tell about it but to understand it, know it and even to celebrate it.

In the final moments of The Grand Parade, Chagall’s painting The Triumph of Music, with its swirling dancers, children and half-human animals presided over by an angel, is projected on the parachute-like heaven, whose gates are open. Suspended high above, a woman in a red dress sits quietly. She is motionless and contemplative, as if waiting…for something.

New York University Professor Carol Martin is the author of Theatre of the Real (2013) and editor of Dramaturgy of the Real on the World Stage (2012), both from Palgrave Macmillan, and editor of In Performance, a series of plays and performance texts distributed by the University of Chicago Press.