After a recent pre-opening run-through of Young Jean Lee’s Straight White Men at Columbia University, the playwright and director, sporting distressed jeans and a leather jacket, posed questions to her audience. “Did you know what that character’s problem was?” she queried from a chair onstage. As onlookers replied, she listened intently and rapidly typed out responses on her laptop. “Did you think and feel beyond the family stuff? What did that scene make you question?” Lee pressed for answers with dramatic flair. At one point, an audience member was caught off-guard mid-response. “Forgive me,” said the accomplished monologist and veteran performer Mike Daisey. “I’m not used to dissecting a play in this way.”

In the theatrical universe of Young Jean Lee, unorthodoxy tends to be the rule, not the exception. Lee has made a name for herself by consistently tackling what she calls “the last show in the world” that she actually wants to make. These worst-case-scenario plays have included a solo show about depression and dying (We’re Gonna Die, for which she won an Obie award); a Shakespeare adaptation (Lear, complete with dazzling Elizabethan garb); and an assortment of identity-politics plays that subversively and overtly combust the form with adventurous aplomb.

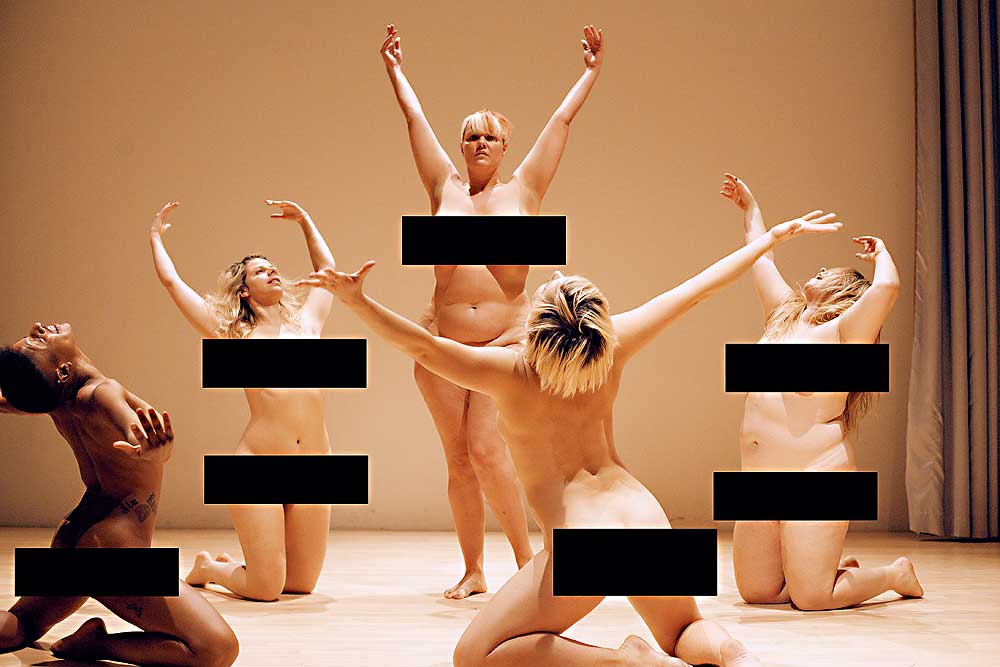

These latter works include Songs of the Dragons Flying to Heaven, which ingeniously addressed Asian-American identity (published in the Sept. ’07 issue of this magazine, it was Lee’s first show to tour internationally); The Shipment, a sly riff on black identity; and Untitled Feminist Play, a wordless show that featured nude dancers addressing issues in feminism. The latest of these identity plays with a twist, Lee’s Straight White Men, opens Nov. 7 at New York City’s Public Theater.

“She simply doesn’t shy away. From anything. It’s an incredibly fertile place to collaborate,” says performer Pete Simpson, who has worked with Lee since 2004, as well as with Blue Man Group and Elevator Repair Service. (Straight White Men is his fourth Lee collaboration.) “In the early days, amidst the stakes of her trying to establish herself, there was an all-or-nothing energy to everything—a giddy, apocalyptic humor.” That dark humor still pervades her work. The laughs one hears at a Lee play can sound explosive, then shocked, then apologetic and perhaps timid—as if the audience is wondering whether they should be laughing at all.

“She deliberately has these curve balls,” says Charles Helm, director of performing arts at the Wexner Center for the Arts in Columbus, Ohio, which has developed and presented a number of Lee’s shows, including Straight White Men. “You start to wonder, ‘Is this supposed to be funny? Do I have permission to laugh?’ And it forces you to question where you are relative to the questions she’s posing.”

“Young Jean’s also the only writer or director I know who has no problem posing textual and structural problems to the show’s cast, and employing those suggestions—which results in a high-morale ownership of the process,” Simpson says. Lee also often poses questions to her followers on Facebook, resulting in a kind of crowd-sourced dramaturgy. “This speaks to the high degree of confidence she has in her directorial/textual voice,” offers Simpson. “She approaches the culling of these extra-sourced ‘idea avalanches’ from a place of confidence and rigor-of-mission.”

Lee’s openness and rigor has paid off not only in international tours, commissions and a stack of prestigious awards—including two Obies, a Doris Duke artist award and Guggenheim Fellowship—but in widespread critical acclaim. Time Out New York has called her “one of the best experimental playwrights in America,” while the notoriously tough-to-please New York Times critic Charles Isherwood wrote in his review of Untitled Feminist Show, “Young Jean Lee is, hands down, the most adventurous downtown playwright of her generation.”

It’s hard to argue with that assessment—the title alone of Straight White Men indicates that Lee is up to something of considerable scope. American Theatre sat down with her to find out more.

Is it true that you started off in academia?

I was in a Ph.D. program at Berkeley, studying to be a Shakespeare professor. I had no artistic aspirations—I was training to be a literary critic. I went to a therapist because I was so miserable. She was like, “You’re not depressed. How could you be happy when you hate everything you do all day long?” She asked me to say, off the top of my head, what I wanted to do with my life and I said, “I want to be a playwright.”

That thought had never even really crossed my mind before. I was embarrassed, but she was like, “Well, let’s talk about this.” It turned out that I was only studying Shakespeare because I secretly wanted to be a playwright. It was like being a veterinarian who says, “I want to be a dog!”

Eventually you found your way to Brooklyn College, where your credo “to make the last show in the world you would want to make” kind of took hold. Can you explain that?

Yes. I was trying to write a play for [theatre professor and playwright] Mac Wellman, and it was such a disaster because of my background. If your brain has been trained for 10 years in theatre criticism, it becomes the stoniest ground for creativity. Everything I wrote was incredibly derivative. I was imitating Mac and Richard Maxwell and the Wooster Group, and I knew it was bad, because I was a critic.

So I was in despair. I called Mac at home and said, “I don’t know if I can be a playwright. Everything I write is so bad. I think I just can’t do it.” He said, “Well, if you’re such a bad writer, then let’s see how bad you can be! If you write the worst play you can possibly write, and it’s bad enough, then you’ll get a good grade and you won’t flunk out of the program.”

That assignment opened everything up—I was so full of self-hatred that it was easy. If I thought, “What would I love to write about?” I’d have nothing. But what would I hate? Everything was there.

I never really liked the Romantic poets, except for Blake—they were all really annoying to me. So I thought, “What would be more annoying than a historical-period drama of the English Romantic poets, talking about life and art in a cottage?” That sounded uncool and horrible on every level. I wrote that play [The Appeal], and it was like a kid playing really sadistically with Barbie dolls. You stick their heads in the toilet, you throw them out the window. The characters were really annoying, and I wrote as badly as I could. When I got bored, I’d restart the scene in the middle without throwing anything away, like a video-game reset. I just did whatever I wanted and followed every impulse, and then the play was done. I was scared to bring it into class, but when we read it, everyone was just hysterical. It turned out to be funny and interesting, because Mac had found a way to tap into my actual creative impulses.

His contrary nature has inspired many. How else did being in that program, with those playwrights, influence you?

Mac is one of the best teachers I’ve ever had, and the reason why is because none of his focus is on his own ego as a teacher. The only question is, “What is the best thing for the student as a writer?” Everyone in the program has to read so much—but I read almost nothing, because Mac said, “You’ve read too much. You need to write.”

Plus, your cohorts read like a greatest-hits list—you were with Thomas Bradshaw…

…Kate Ryan, Karinne Keithley Syers, Kelly Copper. I had never been in a functional situation in my life, and suddenly I landed in this completely healthy environment. I always tell people I had a totally happy artistic childhood because I started at 29. I haven’t had trauma around a project. Mac got me when I was a baby, and he was such a good parent that he trained my brain to expect healthy relationships—and I think that’s a big part of why my career has been so charmed. I still get blocked and have problems, but in terms of basic self-esteem and self-worth and not getting destroyed by things, I’m okay, and gravitate toward healthy people.

That’s kind of been the key to everything—just how good those relationships have been. I’ve never felt exploited or mistreated. That’s all thanks to Mac.

Your idea is to tackle the last thing in the world you want to make, but over time, does that flip and become the thing you want to make? If not, how do you sustain that discomfort?

It’s gone away from the thing that I hate, and now it’s more the thing that I don’t know how to do at all, or the thing that’s really hard to do. So with Untitled Feminist Show, I was never like, “Ah, I love making a show about feminism”—these projects are very masochistic. Sometimes I wonder if it’s unhealthy, because I don’t get to build on prior skills. Every show I have to learn a new skill set from scratch, which basically requires me to work nonstop. For Straight White Men, I had to teach myself how to write a naturalistic play—which is a really hard thing to do if you’ve never done it before. So every play has this horrible, growing-pains, learning-curve aspect to it.

How did you teach yourself how to write a naturalistic play?

You just read a bunch of naturalistic plays and you dissect them. I have a genius dramaturg, Mike Farry—he’s worked with me on every play that I’ve ever written. None of my shows would be the way they have been if it weren’t for him. There’s a lot of trial and error and a lot of rewriting.

It sounds like there’s a stark contrast between the happy artistic childhood and the masochistic constant reinvention of the wheel. How do you manage the masochism?

Um, alcohol? [laughter] I’m having to force myself to do things like cook and exercise and sleep, so that I don’t get really sick. That’s a constant struggle for me—“Do I need to do this every time?” I see what happens to people sometimes—to artists—who just start doing easier and easier things, and it’s like all the power goes out of their work. I feel that the torment I go through gives the shows an energy. There’s a desperate quality to all of my work.

Your shows are super alive, like live, raw nerves.

Exactly. And I think that for my process, the key is to have enough scaffolding around me—like my company and the theatres I work with—so that I can sustain that level of pain. Every show involves so many people putting in so much work to make things happen—I just have this little part in the middle of it, where I’m just like…

That sounds rather modest.

But it’s really true! I’m more of a central cog. It’s really a collective endeavor.

Do you generate dialogue with actors and performers and then sculpt it?

Normally we talk about stuff in rehearsal, and then, based on what we talk about, I go home and write. I come in, once I’ve written the thing, and that’s when everyone pitches in. Straight White Men was a little different, because I didn’t know how to write naturalistic dialogue. The first draft of it, which we did at Brown University, was built out of improv with the actors.

The scripts are really collaborative. I’ll bring in a line and ask how to fix it, and everyone in the room just screams out stuff. My dramaturg is involved in the writing—it’s a team effort. There’s no way I could have written any of those plays on my own. That’s an important distinction between me and other playwrights—it’s never me alone in a room. It’s not springing forth from my brain. It would be interesting to give my texts to everyone who has been on an artistic team and ask, “Tell me what things in this play were your idea.”

Because it would be such a jumble?

Absolutely. Most of it originates with the actors and dramaturg. That could be a worst-nightmare scenario: Me having to write something completely on my own. There’s also audience feedback. I get constant feedback, and when someone shares an idea, that trickles into the writing. I’m sort of like a curator, where all this information is coming in all the time.

How does your process intersect with social media?

I’m in front of my computer all the time writing. And every now and then a question will come up, and my collaborators aren’t there and I need instant response. If I finish a draft of something and I need someone to read it, I’ll ask, “Who can read this by the end of the day today?” I’ll have six people read it and e-mail me feedback. It’s hugely helpful as an immediate resource. People have told me it’s a genius marketing strategy, but, I mean, I pay people to do marketing for me so…

You weren’t plotting and scheming.

No. It’s not my job to do the marketing. I only post stuff when I wonder how people will respond.

In an interview you did with Richard Maxwell for Bomb magazine you said, “Failure is basically my M.O. in everything.” Let’s talk about that.

I think failure is connected to masochism. For a lot of writers, there’s a pleasure in mastery: You’re a master of this form, and what you’re writing isn’t shit. For me, during most of the process, what I am writing is shit, in my opinion. But it’s like, we have to go through that in order to get to where we want to go; 90 percent of the process is just sucking and failing. I don’t think that’s an exaggeration. Everybody is failing, and it’s hard, but there’s always forward momentum—it’s always getting better as we go along. Still, that’s what makes the beginning of the process almost unbearable.

We’ve had presenters say, “We don’t want this piece anymore,” based on the workshops, which are so terrible—not “false modesty” terrible, but so terrible people pulled their funding. That’s why failure is so essential—we couldn’t do it without that part, the part where we’re failing and we throw it away and start from scratch.

I remember a marvelous early iteration of Untitled Feminist Show at the New Museum that was full of text, and I couldn’t believe the show eventually became wordless. In the same Bomb interview you said, “The hardest thing for me in making theatre that is political is trying to trap the audience so they can’t escape through ways of their dismissive loopholes—by saying, ‘I don’t want to be preached at.’” And yet your plays never feel preachy.

Our audience is so jaded and slippery that pretty much everything that I do can be dismissed, left and right. With Straight White Men, all of the feedback, up until this point, has been getting less and less dismissive. But that’s why I am constantly testing.

Tell me more about Straight White Men.

When I was at Brown doing the first workshop, there was a room full of students, people of color and queer people, a very diverse room. And they started talking very harshly about straight white men. I said, “Okay. Now I know all the things you don’t like about straight white men. Why don’t you give me a list of the things you wished straight white men would do that would make you hate them less?”

So they told me all these things, and I wrote down the whole list, and then I wrote that character. And they all hated him. They hated him.

You wrote the character that was supposed to be the embodiment of a good straight white man? A utopian version?

Yes, and they hated him because he was a loser. And that’s what made me realize that, in spite of all these social-justice values, in our peer group, being a loser is worse than being an asshole. It kind of revealed our continuing investment in the patriarchy. So that became interesting to me in the play, and this character became a litmus test.

The play is about a family of straight white men who come home for Christmas together, and they are super P.C.—not in an annoying way, just very politically aware and sensitive. They’re not assholes. They aren’t like David Mamet or Neil LaBute or Adam Rapp characters—they are cool guys, and they really love each other. They are very straight white male, but very loving.

So they are in this family situation, and one of them is the utopian character based on the feedback from the Brown students—he’s a son, and the play is about how his two brothers and father are driven insane by him being the way that he is, which exposes their actual value systems. That’s the movement of the play, and I want the audience to kind of get caught in that bind of, “Oh, well, we say we want straight white men to be like this, but we actually want them to be like this. And that says something about my investment.”

Can you give me an example of this?

Everyone at the workshop was like, “I want a straight white man to sit down and shut up. I want him to take a back seat, to take a supporting role. I don’t want him to be aggressive. I want him to be passive and sit there and take it. I want him to listen. I don’t want him taking the head role or the biggest job or to be going after the biggest stuff. I want him in a supporting role to me.” And like…I don’t want to date that guy! Do we actually want that? No, not according to our value system.

So the audience is supposed to get trapped in this kind of bind, this disjunction between the desire for social justice and the desire for things to stay the same, and for people not to be losers, and to be aligned with power. The audience can say, “Oh, this play is about straight white male assholes. I am completely distanced from it and dismiss the utopian character.” But they’re not assholes. And they’re also trapped if they say, “That character is lazy. That’s his problem,” because he’s not lazy. There are loopholes that the audience is using so that they don’t end up trapped by their own hypocrisy.

Doesn’t your company have a T-shirt that says, “Destroy the audience”?

Yeah. That’s because every play has malicious intent against the audience—not so much malicious as destructive. I think this comes down to the fact that the thing that I hate the most is complacency. I don’t like it when people think that they know everything and they’re right and they are satisfied with themselves. One of the things I believe in most is self-critique and self-awareness. So every show is a challenge to myself, even in the way I approach it—even if it’s the last thing in the world I want to do, I’m forced to change.

What I am going for with every show is to get in the way of the audience’s self-complacency, or to put a little piece of gravel into their brains that irritates them. That’s my goal with every show, and that’s what “destroying the audience” is about. Correspondingly, every show I’ve ever done has forced me to change and become a different kind of person and a different kind of artist.

How has each show changed you?

With Straight White Men, it’s really prevented me from feeling totally self-righteous as an Asian female. I mean, “I’m a woman of color! I can scapegoat the straight white guy! I’m not a person of privilege! I’m doing great things for the world just by totally selfishly pursuing what I want, because I’m making the world more diverse!” A straight white guy can’t do that. He can’t say, “I’m making the world a more diverse place by just doing whatever I want”—there are expectations on him that require him to do something. So working on this show has sort of forced me to confront my own hypocrisy and challenge my sense of how committed I am to social justice—how big a hypocrite I am. It’s also forced me to stop being so snotty about naturalistic theatre, you know? It’s really hard to make.

It’s really hard to make anything—and it’s really hard to make good theatre. Period. No matter what kind of theatre it is. I think I’ve been more generous toward experimental theatremakers in the past because I know what they are trying to do—and now I’m realizing naturalistic theatre is really equally difficult, if not moreso, because you’re constrained in more ways—there’s less freedom. So working on a naturalistic play is probably going to change me. My brain has been rewired to think in terms of character and plot. I don’t know if I can just get rid of that, you know? I’m sure I’ll be able to write nonlinear things again, but I’ll be writing them with the knowledge of what the linear version would be.