Zelda Fichandler, cofounding artistic director of Arena Stage in Washington, D.C., died last week at the age of 91. Inarguably one of the pioneers and founding mothers of the American resident theatre movement, Fichandler, in addition to running Arena for four decades, headed of NYU's Graduate Acting program in the 1990s and served as artistic director of the Acting Company after leaving Arean. We asked colleagues, collaborators, and students for their thoughts about Fichandler's unique contribution and legacy. -Ed.

It Was Always Personal

As seen through the frame of American theatre at the midpoint of the 20th century, the idea of Zelda Fichandler as a producer was unlikely casting—or, perhaps, to use a phrase to which we’ll return, nontraditional casting.

Most producers back then were men, inflamed by the hip-hooray and ballyhoo of the commercial theatre. Zelda was as far away from the self-promotional solipsism of a David Merrick as you could be and still use the word “producer” to describe them both. She disdained interviews and couldn’t bear to have her photo plastered in the papers; she’d much rather devote her acute intelligence to a position paper than a press release any day. When a purely commercial opportunity beckoned from a northerly distance, she went screaming in the opposite direction. If, in the 30 years I knew her, both at Arena Stage and at NYU’s Graduate Acting Program, she ever hung around for an opening night party, toasting herself with champagne, I never saw it; I’m sure she spent the evening back up in her office, drafting a memo about not-for-profit funding or creating a burgeoning “to-do” list on a pad of yellow legal paper, late into the night.

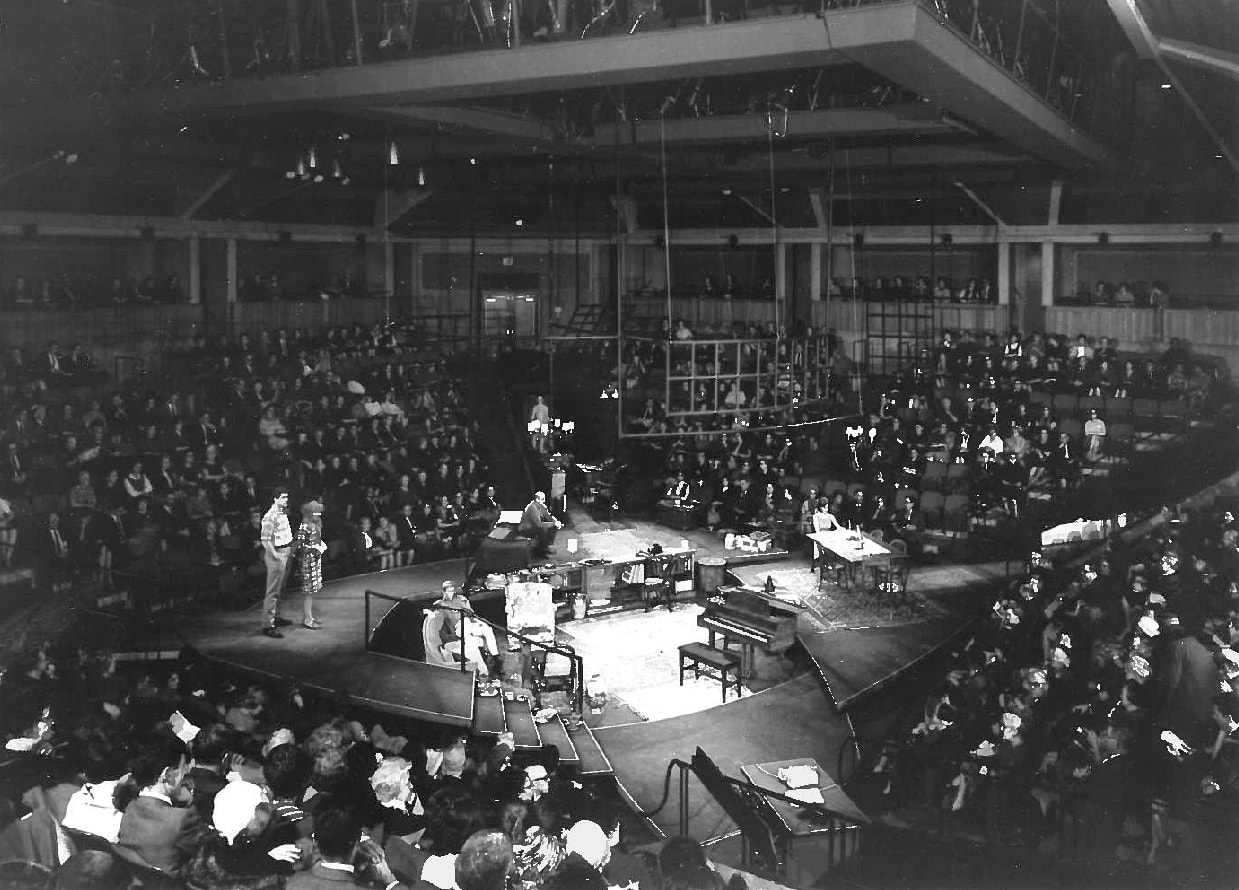

Not for her the bright marquees or gilded proscenium arches that enthralled the Broadway Bialystocks. Perhaps that’s why she embraced the idea of an arena theatre so passionately: nowhere to hide; the focus on dialogue and discourse; the rethinking of human interaction in cubic space, not the artificial choreography mandated by a box set. For Zelda, the Arena was, first and forever, an arena: a forum where conflicting ideas could be battled out until the last righteous man or woman remained standing.

At the center of those ideas was always the essential instrument for broadcasting passionate thought, the human being—or, in its quotidian representation, the actor. I say this not to denigrate the actor, by any means; I simply mean that Zelda loved people and their problems—their motivations, their contradictions, the “Shadow” that T.S. Eliot wrote about which falls between the motion and the act. She was obsessed with the human psyche, and actors were the best way to explore that vast, furrowed landscape. Had she to live her life over again (and it was three normal lifetimes worth), she’d have been a psychoanalyst. I think she was always more interested in actors than characters; characters were limited by even the best playwright’s imagination. Human beings, however, were infinite and circumvented neat or easy conclusions.

That may be why Zelda was always drawn to Chekhov, Miller, and Odets; they came closest, in her mind, to capturing the elusive conundrums that human beings bring to real life. She always loved Bessie Berger’s line in Awake and Sing!: “We saw a very good movie, with Wallace Beery. He acts like life, very good.” Her taste in playwrights notwithstanding, she was hardly grim or humorless to anyone who knew her; she used to say, “I love a good joke—but it has to be a good joke.” But Zel rarely tried her hand at Molière or Kaufman & Hart or musicals; those she left to the extremely capable hands of associates such as Garland Wright or Douglas C. Wager. I suspect that comedies or musicals simply didn’t intrigue her mind as much; by their very definition, they must always conclude—usually in a happy fashion—and Zelda believed that “real life” always held a next chapter.

Few things made her happier than gossip: She loved it when I, or one of my colleagues, walked into her office and spilled the beans on some post-opening-night tryst or an ongoing affair between classmates that had escaped her attention. These were secret chapters in the lives of people close to her—and the more incongruous the assignation, the better. She always embraced the unexpected as the best possible turn of events.

Her great pleasure was in the unexpected revelation of people. Zelda would kvell her deepest kvells when an acting student made an unforeseen breakthrough in a production. “Wasn’t she amazing?” she’d ask rhetorically (she was big on rhetorical questions), like a career botanist observing the bloom of an exotic flower.

When I first interviewed with her in 1988 for a job at Arena, we attended a visiting production of the Abbey Theater’s Juno and the Paycock, directed by Joe Dowling, on Broadway. (True to form, Zelda loved it and immediately hired Joe—whom she hadn’t met before—to direct the production with the Arena company.) As we walked to a restaurant on West 44th Street afterwards, I nattered on about my meager achievements in the theatre, and I could see Zelda’s eyes glaze over; a recitation of my résumé had clearly not provided enough to spark her prodigious curiosity. A polite but semi-opaque film had been drawn between her and my ambition to work at a great theatre. But, as we were seated at the restaurant, I asked her if we could switch seats, as I was (and am) completely deaf in my left ear. “Really?” Her ebony eyes swelled behind her immense designer frames. “Since when?”

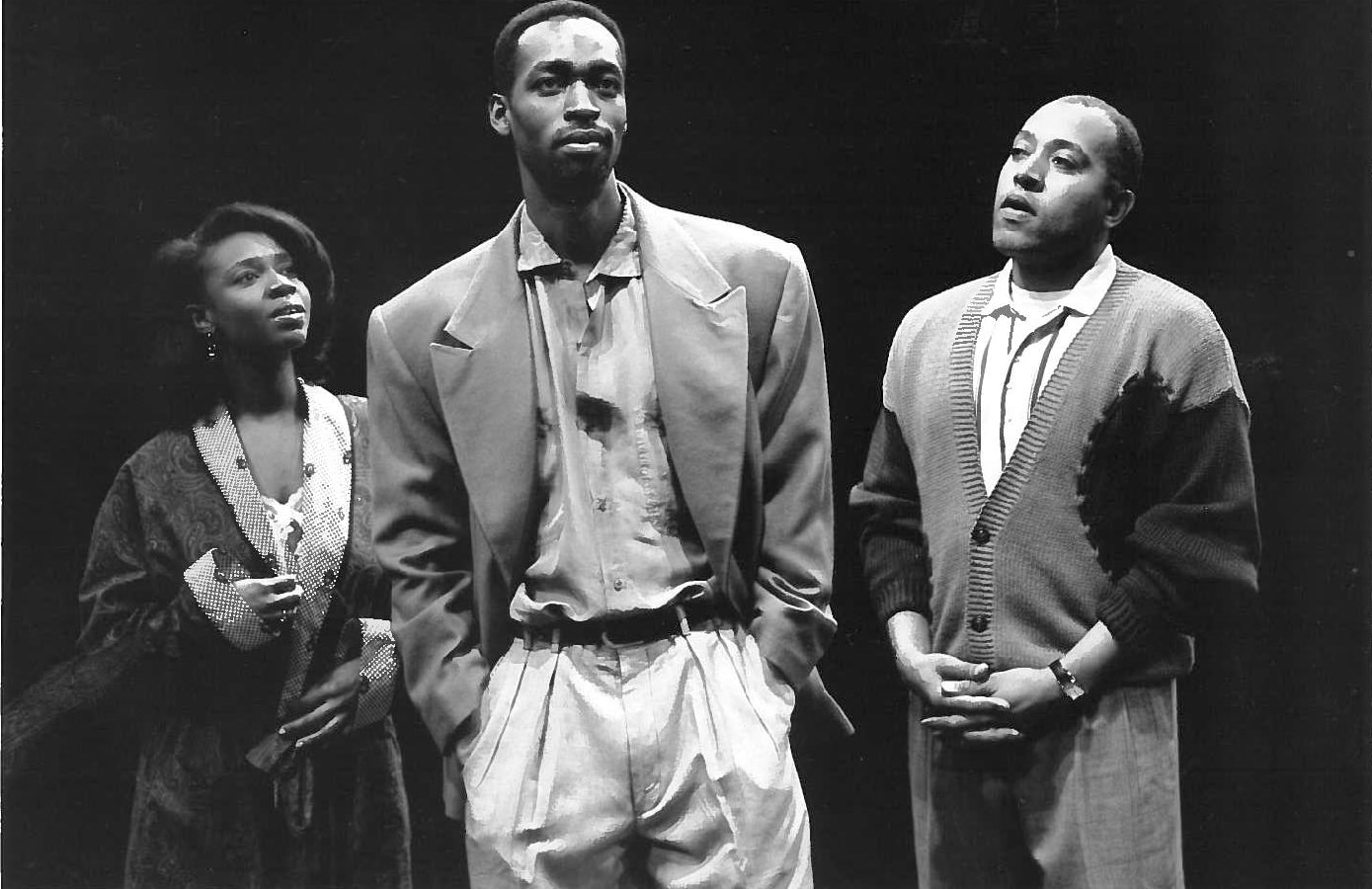

The one area that, in my opinion, stymied her was the terrain of multiculturalism. Zelda believed in the flowering of human potential as much as any human being I have ever met. Her efforts in giving opportunities to actors, students, writers, directors, designers, producers of color were second to none during the time in which she had opportunities to wield at her disposal. As early as 1968, she tried to create the first “nontraditional” ensemble in the American theatre. In the 1980s, she took on the challenge with renewed vigor, diversifying the Arena company once again, hiring associate artists such as Tazewell Thompson, commissioning plays by diverse writers with diverse stories, and digging deeply into the ranks of aspiring actors for the graduate program to produce an ensemble that looked like America. Working in tandem with lighting designer Allen Lee Hughes, she created a fellowship in his name at Arena Stage, an incredible program that has encouraged and developed the next generation of theatre artists of color.

And yet, somehow, I believe Zelda never felt she had done enough in this regard. Ironically, for someone who enjoyed the irresolution of an ambiguous dramatic message, Zelda couldn’t quite bring herself to believe that the diversification of an American art form was—and always will be—a process. Zelda’s can-do resolve wanted to make sure this mission was definitively concluded, but, in this one arena, even Zelda, with her immense will power, couldn’t knit together the warp and woof of human history. It’s an ongoing experiment, and to my mind Zelda has never been given enough credit for what she did manage to achieve in diversifying the American theatre.

I heard that Zelda was not well and that she was declining quickly during the last week of July. On Thursday night, I watched Hillary Clinton accept her party’s nomination as president and give a pretty darn good speech (Zel would have had a few notes for her, though). I went to bed and when I awoke early the next morning, I learned that Zel had passed away during the night—about half an hour after Hillary’s exit from the stage in Philadelphia. What timing! Did Zelda, in her serenity, muse to herself: “You know what? I created a major American theatre, the first resident company to send a play to Broadway, the first to tour the Soviet Union, the first to win a Tony Award, and the first to provide a platform for hundreds of major artists. I transformed an MFA acting program into one of the country’s finest. Let someone else crack a few ceilings for a change: Here you go, the torch is yours.”

And then, to paraphrase the end of one of Zelda’s beloved Chekhov’s plays: She would rest, she would rest, she would rest.

Laurence Maslon, arts professor and associate chair of NYU’s Graduate Acting Program

A Revolution, Lived Every Moment

Zelda Fichandler was, among so many things, a world-class quoter. Her brilliant, inspirational speeches, her capacious essays, even her letters to government officials and funders, draw quotations from poets, philosophers, physical and social scientists, novelists, lots of Russians, and, of course, playwrights. She wrote and spoke as a reader, because Zelda was forever reading the world, forever studying exactly what it means to be human.

She often quoted this Burmese saying: “The fish dwell in the depths of the water, and the eagles in the sides of heaven; the one, though high, may be reached with the arrow, and the other, though deep, with the hook; but the heart of man at a foot’s distance cannot be known.” This unknowable “foot’s distance” between one heart and another was, I believe, Zelda’s life’s work. She never lost track of it. In a world of mission drift and purpose distraction, Zelda’s genius was precisely her ability to keep her eyes trained on this infinitely small space, on what was most important.

Yes, the nonprofit art theatre would have grown differently (if it grew at all) had Zelda not shown us the way to realize Margo Jones’s dream of a regional-resident-repertory movement. Yes, the path of new plays into New York might have taken many more years to forge had it not been for Arena’s The Great White Hope in 1968. The acting company ideal—the body and soul of our field’s founding impulse—might have died aborning had she not zealously kept it alive for almost four decades. Yes, we would have needed someone else to integrate theatre in the nation’s capital; to fight for diversity at every level of a major institutional theatre; to inspire a generation of American actors (as she did leading NYU’s graduate acting program); to imagine the theatre field as a field, articulate its values, and then question, question, question the very revolution she incited. It may be too much to say that without Zelda the nonprofit theatre community wouldn’t be here; it’s possible, though, that without her leadership we wouldn’t know what we are here for.

It may be too much to say that without Zelda the nonprofit theatre community wouldn’t be here; it’s possible, though, that without her leadership we wouldn’t know what we are here for.

I have spent 35 years working in and mapping this movement she created, and, like so many people she influenced, I can’t say for sure whether she created me or just drafted me as an officer in her evangelical army. Have I adopted her sentence structure? Aped her turn of mind? What would my principles have been had I never crossed her path? The time we shared in recent years felt especially intimate. She had enlisted me to help her with a book of her collected speeches and essays, long in the works for Theatre Communications Group. Later, facing surgery with a difficult period of recovery (she ultimately opted out of the procedure), she asked for my promise to complete the work she feared she’d leave unfinished. It was the easiest promise of my life. For several years then, including from across the country, from D.C. to Seattle, we were surrounded by her extensive writing, reading Zelda together—the world according to Zelda. And what a vast, complex, humane world it is!

Art is our mostly doomed attempt to describe life even as we live it. (Here I imagine Zelda, who famously brought Our Town to Russia, quoting Thornton Wilder’s Emily: “Oh, Earth, you’re too wonderful for anybody to realize you. Do any human beings ever realize life while they live it?—every, every minute?”) I believe that Zelda—as founder, director, producer, teacher, writer, rabbi—sought to do just that: fully realize life while she lived it.

In her final years, she struggled to make sense of the “long revolution” she started. Not content to rest on her accomplishments, Zelda couldn’t stop rewriting. She refused to quote herself. She had to know what was happening now, what was most important now. The work was never done. She could never know enough, could never suspend her ceaseless commitment to realize the unknowable.

Todd London, executive director/professor at University of Washington School of Drama, who is working to complete Fichandler’s memoirs

The Encouraging Embrace

I came to Arena Stage in 1974 as an intern fresh out of Boston University with my MFA in directing, for a 10-week period to assist Alan Schneider on the world premiere of Elie Wiesel’s play The Madness of God. Those 10 weeks turned into 25 consecutive years.

Our world has lost a blessed, powerful, tenacious, inspired visionary.

Zelda gave us so many of us the chance to live and grow within the encouraging embrace of an amazing creative community of possibility. She worked from a deeply feminine understanding of the importance of allowing people working at every level of the organization to feel they could speak up and contribute, but you always knew she held the reins; you were working for an incredibly strong, willful, prodigiously gifted visionary leader.

As I came to know her more personally, I was surprised to discover that she was in certain respects quite shy and somewhat fearful of speaking in public. As a result, she never ever allowed herself to speak extemporaneously; she always prepared her remarks. And the careful thought she devoted to that exercise yielded some of the most amazingly effective, powerfully insightful, and inspiring public addresses, and a body of writing on theatre and its place in the world—theatre as an instrument of civilization no less important to the life of a community than a church, a major library, a museum, or a university.

Though she was inarguably a formidably gifted stage director, directing was never her first love. She derived far more personal satisfaction from shaping the image and the artistic culture of the company and defining its place in society, forever trying to solve the riddle of how best to consummate the artist-to-audience relationship, and of how theatre becomes indispensably important to the daily life of the community.

Arena’s ensemble of resident artists and theatre practitioners thrived within a challenging and rigorous culture of artistic expression fueled by passion and purpose—a collaborative collective of “storytellers” making theatre together, all imbued with her underlying humanistic sense of promulgating hope for the human condition. She touched and opened so many hearts and souls though her work, transforming the lives of artists and audiences alike, and indeed, theatre in America for all posterity.

Zelda defied and triumphed over the crass capitalistic assumption that the professional resident theatre movement she championed was easily dismissed as merely a commercial enterprise that failed to make a profit. She elevated the stature of the art form by prioritizing the centrality of the artist over the necessities of commerce. She pioneered a way to encourage the community to join her in recalibrating the precarious balance between fiscal stability and the pursuit of artistic excellence, reaping priceless profits, not in dollars and cents, but in the hearts and minds of audiences and artists.

I was incredibly fortunate to be selected as her successor following her decision to step down and focus the full force of her creative energies on leading NYU’s Tisch Graduate Acting program. I was both thrilled and incredibly intimidated by the prospect of even attempting to fill her shoes. I remember sharing a moment of self-doubt with her as to whether she was really in fact okay “passing the torch” to me. She thought for a moment—and forgive me for paraphrasing—she said not to worry: “Maybe you can’t pass the torch; you can only pass the fire.” So she did.

Douglas C. Wager, associate dean of Theater, Film, and Media Arts at Temple University

Wise and Questioning

Zelda was a beacon for me. When I completed my six-month active duty in 1957, I was anxious to start my career in the theatre in New York, of course. But something made me investigate what seemed to be a small awakening of theatres in cities around the country. I chose to write to Zelda at the Arena Stage in Washington, D.C., followed by inquiries to Nina Vance in Houston, Jules Irving/Herb Blau in San Francisco, and K. Elmo Lowe at the Cleveland Play House—about five or six in all. The rest replied with a form letter stating that no jobs were available, but Zelda’s answer was personal. Although no jobs were available with her either, she was positive in her encouragement to explore, reach out, and take chances.

We became good friends. She was always available, even after she took on the challenge of chair of the graduate acting and directing program of the Tisch School of the Arts at New York University. She was wise and questioning; she listened, and her responses to my questions were always enlightened and provocative. She was truthful and insightful and challenging.

Zelda was a pioneer and an artist of deep resources. She was special to my life and I am grateful for her wisdom and her caring. We were good friends, but she was much more than that to me: inspirational and brave.

Gordon Davidson, founding artistic director, Center Theatre Group

Truth in Contention

Copernicus tells us: “At rest, in the middle of everything, is the sun.” For me, it’s Zelda who will always hold that place.

Above all else, I think she valued ideas, and her nurturing radiance was her colossal intellect. When I met her, I was 30 and I believed that my quest, my purpose, was to discover the absolute truth of human existence—that I must uncover some coherent, unalterable kernel that would envelop all the contradictions of human experience. That there was a perfect, unshakable, immovable idea at the center of it all.

It was Zelda who made me understand that I was misguided in believing that the essence of human experience was a pure, indivisible, fixed thing. She taught me that any truthful perception of life would be contained in the creation of ideas, not in a simple thought or a pure feeling or an unchanging belief. An idea was something achieved, or created, by wrestling with experience and learning and was crafted, ever so carefully, over time. Revising, editing, deleting, inserting until it took its true shape. It must first and foremost contain active conflict, contradiction; it must hold opposite, contradictory forces, locked in a never-ending balancing act. She made me see the truth of the world in its contradictions, to be in love with paradox, to be suspicious of those who have answers, and to value those who eternally seek the ultimate truth in questions.

Though her intellect was vast and wide-ranging, it landed, ultimately and inevitably, on theatre. The essence of drama—the conflict of opposing forces or ideas—was how her mind naturally perceived human experience. Where else could she have gone but theatre? Her method of thinking was theatrical. It didn’t happen in solitary mediation; it was deliberation by dialogue. By engaging with other human souls, she found her opinions, her poetry of ideas. She tested her hypotheses on others, she collected her evidence by communicating with people. Of course she loved actors: They are poets who use their bodies and minds to convey ideas and imagery. Their practice of ritual reenactment perfectly matched her own instinctive means of grasping and then communicating the perception of living.

The essence of drama—the conflict of opposing forces or ideas—was how her mind naturally perceived human experience. Where else could she have gone but theatre? Her method of thinking was theatrical.

I think her greatest accomplishment might well be her articulation of the importance of the creation of spaces for artists and audiences to meet. Her life’s work of creating, inhabiting, and sustaining vibrant artistic institutions was in itself a distinct artistic practice, as significant as the practice of acting, writing, directing or designing. She made me understand that every last detail of an audience member’s experience of a space is an artistic question. To her, from the very first impression of a production that a potential audience member received to the parking of their car, from the experience of picking up a ticket to the ambience of the bathrooms—these were all vital concerns of the artistic director. And not in the customer-service sense, but in how these experiences impact the expectations and mood of the audience member as they sit down in their seat to experience the work of the artists at hand.

Ultimately she believed that human relationships based on true, deep listening to each other were not only the building blocks for creating art, but are the essence of all human endeavor. She believed that we only find the light and the truth in each other.

It’s hard to accept that my own personal sun, my Zelda, has set with some ultimate finality. I will have to believe that some of her essence radiates on still, and enlightens the dark world, in and by the many, many of us who were shaped by her, who must live on now without her.

James Nicola, artistic director, New York Theater Workshop

An Illuminating Force

I think continually of those who were truly great.

Who, from the womb, remembered the soul’s history

Through corridors of light, where the hours are suns,

Endless and singing. Whose lovely ambition

Was what their lips, still touched with fire,

Should tell of the Spirit, clothed from the head to foot in song.

And who hoarded from the Spring branches

The desires falling across their bodies like blossoms.

—Stephen Spender

It is very clear: I am a lucky so-and-so. I was born under a most propitious star. The planets were all brilliantly aligned. Jupiter was ablaze somewhere in the midheavens, rising in my tenth house of great expectations, as a comet’s tail passed over conjunct or trined or sextiled with mercury, making me a student for life, interminably conscious of receiving and filtering good news and glad tidings—birthed in double Gemini, with a new moon in Capricorn. This cosmic milky way formation would lead me on a life path journey that would connect me, in the still formative period of my life, to she who would shape mist into substance: Zelda Fichandler.

Zelda was a dear friend, mentor and mother figure. She brought me to Arena Stage in 1988. It changed my life. We wrote letters/cards/notes to each other—even though sometimes in the same building, on the same floor—for almost 30 years. We spoke by phone, endlessly or in short spurts on a wild variety of topics, several times a month, and in the last years, two to three times a week. She provided me with a reading list of plays and authors I must want to know. She entertained me with memorized lyrics of standards from the 1930s and ’40s. She read drafts of my plays, giving me incisive, perceptive, and cogent notes. She dramaturged all my productions while near at Arena Stage, from NYU or the Acting Company, and from as far as Cape Town and Tokyo. Despite a horrific argument many years ago over my wanting to work independently elsewhere and her insisting I stay within the company as an associate, we became deep close friends. I will love and miss her forever.

Zelda: complex, tough, tender, inspiring, imaginative, inventive, erudite, difficult, unique, caring, loving, political, brilliant, brave, bold, tenacious, remarkable, renegade, witty, relentless, stylish, classy, resilient, empathetic, fallible, uncompromising, vulnerable, visionary, vain, genius, magician, phoenix, soulful, radiant, transcendent, splendid.

And now the planets have clashed and the whole world has shifted. Out of a chaotic sky and the times teeming with lightning; leaning in sorrow, in the saddened aftermath of your passing, artists are left dashed, shocked and shivering, fending for ourselves, reaching for the eternal dream and the transitory light you left us. How are we to catch our breath again?

We receive you and with free sense at last, and are insatiate henceforward,

Not you any more shall be able to foil us, or withhold yourselves from us,

We use you, and do not cast you aside—we plant you permanently within us,

We fathom you not—we love you—there’s perfection in you also,

You furnish your parts toward eternity,

Great or small, you furnish your parts toward the soul.

—Walt Whitman

Tazewell Thompson, playwright/director, former artistic director of Westport Country Playhouse and Syracuse Stage

Words Well Chosen

I first met Zelda in 1985 when I joined the board of Arena Stage. We worked together for many years at Arena, then at the Acting Company, and then on the board of Theatre Communications Group. After she moved to New York to chair the graduate acting program at NYU, our professional friendship gradually evolved into a more personal friendship, nourished over many dinners where we talked about art, but also about love and marriage and the many complexities of human behavior that we experienced as women. We were both very private people, so it was a friendship that grew slowly as we built trust and a shared compassion for our own lives, as well as the lives of others.

As I got to know Zelda, I never ceased to be amazed at the integrity of her mind and spirit. In a field that feeds on words, she never used words carelessly. Every time she wrote a new paper or speech or even started exploring new ideas, her thinking was original. She started fresh, building on her past thoughts but never rehashing them. Her vision was wide, but she always spoke to the personal, particularly to the artists she cherished. For her, the artists and the art were one.

In the past few years, as her health declined, we talked on the phone or I visited when I was in Washington. We still talked about art. She was putting her papers together in book form and was reaching to understand the rapid changes in the field today. She read everything and was synthesizing it into her own long view of the field. She was not able to finish this work before she became so ill. But it was always on her mind, and she never lost her curiosity or passion for the theatre.

Zelda revolutionized the field of theatre and led it forward for many decades as our most articulate spokesperson. But she also touched peoples’ lives in very personal ways, inspiring students, sustaining artists, and engaging audiences. We have all been deeply enriched by her. I will miss her dearly as a mentor and a friend.

Jaan Whitehead, trustee emeritus and former board chair of SITI Company

Mayor of Our Theatre Capital

I got my book back from Zelda this week at her shiva. She left it waiting for me at the top of a pile in her study. It was a book that meant a lot to us both: Arthur Miller’s autobiography, Timebends. She asked me for it about four years ago, as she wanted to study it for her own memoir—to understand its associative structure, hurtling from memory to memory in psychoanalytic unity, threaded together by the writer’s intention to figure himself out, almost never in chronological order. It appealed to her in the profoundest of ways—to be psychologically true; to seek structural innovation—because the essential business of reflecting the world, her world, from the inside and out, required a form to fit the largeness of the vision.

Such was Zelda’s probing intention throughout her life: to question and to build, at one and the same time, a framework for celebrating and interrogating the meaning of life as rendered by artists; to build a civic center for world drama that might also be called a home, though it was much less “homey” than it was a capital, a cradle of theatrical primacy, where the actor, the writer, the director, all shared power in different ways, like a government—a little federal municipality of the arts. And Zelda was its president/mayor/presiding officer for half a century.

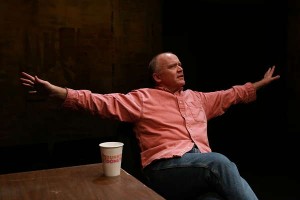

Around the apartment on Calvert Street yesterday were articles and cover stories of note about Zelda. The first that caught my eye was a major interview with her in American Theatre magazine from March of 1991, a month after the closing of Born Guilty, which she directed after a two-year development process—the only world premiere of an American play she would ever direct in her lifetime. I was the playwright. And as I’ve written before, we grew closer after the project’s workshop and premiere than we were beforehand or during the crucible of its launching (it’s often the other way around—relationships with directors can fade as everyone moves on). But she proved to be a mentor later rather than sooner, as I became a producer; her words grew wiser and more profuse as I matured in my ambitions. She only seemed to warm to those ambitions, and to me, more and more, and more and more personally in the writing that she shared.

And over these last years, as she continued to battle through pain and write profoundly, and associatively, in an often unwieldy way, we both kept wondering when I would get my book back; she would promise to bring it to the theatre, but then not be able to make it. I didn’t have the heart to ask for it on my last visit, with Howard Shalwitz, toward the very end. But three weeks later, we were back, and it was waiting there, at the top of the pile, my name inside the front cover, her primacy as an architect of the American theatre movement—and as a frequent partner to our other departed giant mentor, Arthur Miller—very much secure. All was in its place: her place in our lives, and hopefully, ours in hers. She knew she was loved, and she knew what she had achieved. What would last? Whither our direction? These were the continuing questions she would force us to think about for the rest of our lives.

Ari Roth, artistic director, Mosaic Theater Company

The Mother of Us All

Zelda Fichandler is the mother of us all in the American theatre. It was her thinking as a seminal artist and architect of the not-for-profit resident theater that imagined resident theatres creating brilliant theatre in our own communities—a revolutionary idea. Her thinking and her writing have forged the way we were created and the resident nature of our movement. She is irreplaceable, but lives on in every single not-for-profit theatre in America—now more than 1,500 strong. Her legacy stretches from coast to coast.

Arthur Miller wrote in the preface to Arena’s 40th anniversary keepsake book (The Arena Adventure) that Arena had the makings of a national theatre for the U.S. Without Zelda and Margo Jones and Nina Vance, there would not be this robust American theatre landscape. It was a vision like Zelda’s that could lead to a time where my vision at Arena for American work can thrive. She had a remarkable openness to new ideas, and most of all to always, always support the artist.”

Molly Smith, artistic director, Arena Stage

Persistence of Vision

A week after the opening of my production of Juno and the Paycock at Broadway’s Golden Theatre in June 1988, the phone rang in my Dublin office. “This is Zelda Fichandler and I have just seen your production, and I want you to direct it for our company at Arena Stage.” While flattered that she might consider me for such a task, I immediately refused, arguing that I couldn’t possibly recreate such an Irish production with American actors. Zelda never knew how to take no for an answer. For some weeks after that, she called regularly, and finally I agreed to visit Arena Stage with our set designer, Frank Hallinan Flood.

As soon as we entered that magical space, we knew that we had to create the production there. The Arena company, led by Tana Hicken and Halo Wines, were magnificent, and I had the pleasure of working closely with Zelda on a number of subsequent productions at Arena. I have been forever grateful to Zelda that she was so persistent in her pursuit. Because of her I had the chance to develop an American career that I could never have imagined in my wildest dreams.

Persistence was one of Zelda’s most enduring qualities, among so many others. She was also fearless, wise, and filled with a passion for theatre, for writers, for actors, and above all for her Washington audiences.

Zelda was one of that amazing generation of artists who, seeing a huge vacuum in theatre outside New York, resolved to change matters themselves. The courage Zelda and her contemporaries showed is hard to imagine now, with the resident theatre movement spread from coast to coast. When Zelda, Tom Fichandler, and Ed Magnum began Arena in the early ’50s, there was no map and very little precedent to follow. As Zelda herself said so eloquently:

It was, as I say, miscellaneous, whimsical, as whimsical as falling in love: a something that you can’t evade, you can’t avoid, you can’t dodge, you can’t go around. You don’t listen to your parents. You think all obstacles are mythological and that you’re going to have this thing, love, this person you love, this idea, at whatever cost. Your life is made in those moments. It’s a moment of self-donation: “I give myself to this.” So in a very lighthearted but serious way, that’s how it happened.

However whimsical the beginning, the achievement was extraordinary and enduring. Her tenacity and courage, combined with her artistry, were the ideal characteristics to make her the leader of a vital national movement. Her appetite for new work, for reinventing the classics and for the ideal of an acting company working closely together over multiple seasons, made Arena Stage a leader in the burgeoning resident theatre movement.

Zelda’s promotion of young artists came from a deep passion for education and a real understanding of the need young artists have for mentorship. Her tenure as chair of the graduate acting program at the Tisch School at NYU was notable for the range of diverse and skilled actors she encouraged. Her artistic directorship of the Acting Company was a further example of her devotion to young talent. Like me, there are many people working in the American theatre who owe a great debt to this amazing visionary. Her legacy is to be seen in theatres throughout the country. We have all reason to be grateful for her work and her life. She was a unique spirit and may she rest in peace.

Joe Dowling, former artistic director of the Guthrie Theater

Her Leap of Faith, and Mine

Zelda would have us imagine. She would have us do it with courage, drive, and purpose, but she would have us begin there. And above all, she would have us take that leap with faith. She knew this was why humans need theatre: to give ground to our imagination, and in doing so to keep growing new iterations of ourselves in all our wild fragility. But she would go further: She would have what we experience in the harbor of the theatre inspire us to live better lives outside that harbor than the ones we lived before entering.

It was her mission to us whom she guided through NYU’s Graduate Acting Program between 1984 and 2009. In our first semester, we would have class with her. We would lie on the floor and finish the phrase, “As if…”—as if I were a carpenter, as if I were taller, as if I were to reinvent regional theatre, as if the color of one’s skin were irrelevant to one’s ability to play a part….things like that. In her speech at the beginning of each school year, clad in her tailored leather suits, hair perfectly colored and coiffed, this titanic spirit in the tiny frame would quote Apollinaire and invite us to “come to the edge,” afraid of falling, so that we might be pushed off, and only then find our wings—and in turn, our faith.

I had never had an acting class until after I’d been accepted into NYU midway through my senior year of undergrad; I was a science major but squeezed Acting 101 into my final semester so that I might not be wholly unprepared going into what Zelda had helped turn into one of the nations’ top actor training programs. I was very, very green. But for some reason I could feel her faith in me. In a way that is characteristic of great theatre, she used her eagle eyes to show me who I was with both a potentially painful yet ultimately uplifting honesty, saying things like, “You’re a woman now. You weren’t one when you entered this program, but you are now. It’s wonderful to see.”

She taught me to find the inner strength to ask for what I wanted, though I was accustomed to the opposite—to accepting whatever I got without complaint. So I took the lesson: At the end of my second year, I sat in her office and said, “I’d like to play a leading lady. I think I’m ready to do that now.” She smiled and said, “Okay,” or something to that effect. When I saw our casting for the third year, she’d given me exactly what I’d asked for: the lead in Romantic Roulette, Laurence Maslon’s adaptation of Marivaux’s The Game of Love and Chance. (If only it were still that easy…)

Her faith in me continued after I graduated in 1997. By the time we’d finished three years of school, my self-confidence had been painstakingly rebuilt—only to be broken again at the very end when I did not get an agent out of the showcase. I had very few meetings with casting directors, and hardly any auditions for months. I was despairing and terrified much of the time, full of questions with no answers, thinking I had no future in the American theatre. (I learned soon afterwards that if you don’t know what your future is as an actor for only a few months, you’re in great shape.)

And then, in late October of that year, Zelda was holding auditions for her production of Uncle Vanya at her seminal co-creation, the Arena Stage. I auditioned for Sonya, the part I had played in grad school, and she chose me. I could breathe again. Not only that, but during the run, Doug Wager, then Arena’s artistic director, pulled me into his office and said, “Zelda’s giving you an award.” I was deeply puzzled. I remember saying something to the effect of, “What? Why?” As green as I still was, she had given me the Rose Robinson Cowan Acting Fellowship, in recognition of my promise and potential as a future actor of the American theatre.

I was stunned. I did not thank her properly. To this day I have yet to thank her properly, though I’m grateful to this publication for offering me the chance to try. With Vanya, she didn’t just give me a job, or a part that remains one of my most beloved of all time. She didn’t simply give me my entrance into Actor’s Equity, the start to my career, or an award I’d barely had the chance to earn. She gave me something far greater: her faith. And by doing so she restored mine. Bestowed with the belief she had in me, I began to once again believe I might belong in the world I’d dreamt of inhabiting since I was a child. She imagined I might become someone worthy of this award, and she did it with the same matter-of-fact knowingness with which she seemed to do everything—as if she could see the preordained and knew how to will it into being.

A person like that is rare; a woman with the power to use these gifts for the greater good more so (though less and less rare these days). She seemed to both know this and disregard it at the same time. Because her driving force was the knowledge she sought to instill in all of us that in the end, no individual performance, no single accomplishment, is greater than that which it serves: the story which encompasses us all. Whatever work I continue to have in the theatre, it is in no small part due to Zelda. More importantly, I have been infused with the idea that my work is not mine to keep—that it is my responsibility and privilege to be an “actor citizen,” one whose artistic and civic efforts mesh in order to advance a deeper common understanding, and therefore a greater civilization. I take this privilege seriously, and it gives me great joy. (Aw, man—yet more ideas for which I wish I could thank this great lady.)

Though I imagine she can hear me.

Angel Desai, actor

A Lingering Joy

“Are you hearing me?”

Zelda used to say this, looking up from her notes behind fabulous glasses, as she delivered all-school speeches to us, her MFA students in the late 1990s. She wasn’t being stern. She was giving us a chance to configure ourselves in the present moment, something we were learning to do as actors too. Her speeches somehow managed to be inspiring orations and intimate ruminations at the same time.

Her positive impression lingers in so many places and for so many people. For me one of the enduring joys of my attempts in the theatre has been to discover Zelda’s presence in my present moments, reminding me that acting is being private in public; that theatre, like politics, is local; and that a maroon leather suit is something to strive to wear when one is 70.

I heard Zelda again when I picked up the phone and called her about two months ago. I was working on Nora in A Doll’s House. Zelda’s former colleague, our mutual friend, and NYU’s resident smarty-pants, Larry Maslon, had generously given me some research material of Zelda’s from her production of A Doll’s House. I told her I missed her and that I think about her often. She told me that was nice to hear.

Maggie Lacey, actor

Falling and Flying

My first professional audition, in 1983, was a general call for Washington, D.C., area theatres, held at the Arena Stage. I had just graduated from college, and a hot summer of sweltering lawn care employment and living in my old bedroom in my parents’ house had made me start wondering if the world was going to be impressed that I had played Prospero and Falstaff at 20. Something told me they already had people for those roles out here in the real world.

I practiced my monologue over and over in the Arena parking lot (I can’t remember if I went with Prospero or Falstaff). In a frenzy of nervous energy, I climbed up onto an open dumpster sitting in the parking lot. Seemed like a thing to do. I sat up there, looking out upon the world, madly Shakespearing. I was feeling pretty good, until I saw the most forbidding human form I’d ever seen striding toward me. Zelda Fichandler, the queen of D.C. theatre, the leader of the pack, the Grand Duchess, the One. I couldn’t move. She walked past me—it turns out she wasn’t looking at me at all, but at the theatre. I was relieved. The last thing I wanted was to get in trouble with the Great Zelda on my first day of incipient professionalism. I thought I’d escaped her notice until I heard a clear, ironic voice: “Don’t fall in!”

During my high school years in the Virginia suburbs of D.C., I saw many, many plays at the Arena. I didn’t realize then that I was the beneficiary of Zelda’s groundbreaking work (along with Margo Jones in Dallas and Nina Vance in Houston), more or less inventing the regional theatre in America. I didn’t know that these three women had basically founded a real national theatre in America (I propose replacing “regional” in this case with “national”—less condescending, and more accurate), one that lives and breathes with the genuine voices and talents of the whole country, most of it far away from midtown Manhattan. I took it for granted that I could drag my mother or father to Southwest D.C. to see Shakespeare or Miller or Wilder, to have my life changed by great actors like Robert Prosky, Stanley Anderson, Halo Wines, Tana Hicken, and the great, anarchic genius Richard Bauer. That’s where I started forming the idea that my lifelong hobby might become my actual life. I was watching these people do it, gloriously, in front of me.

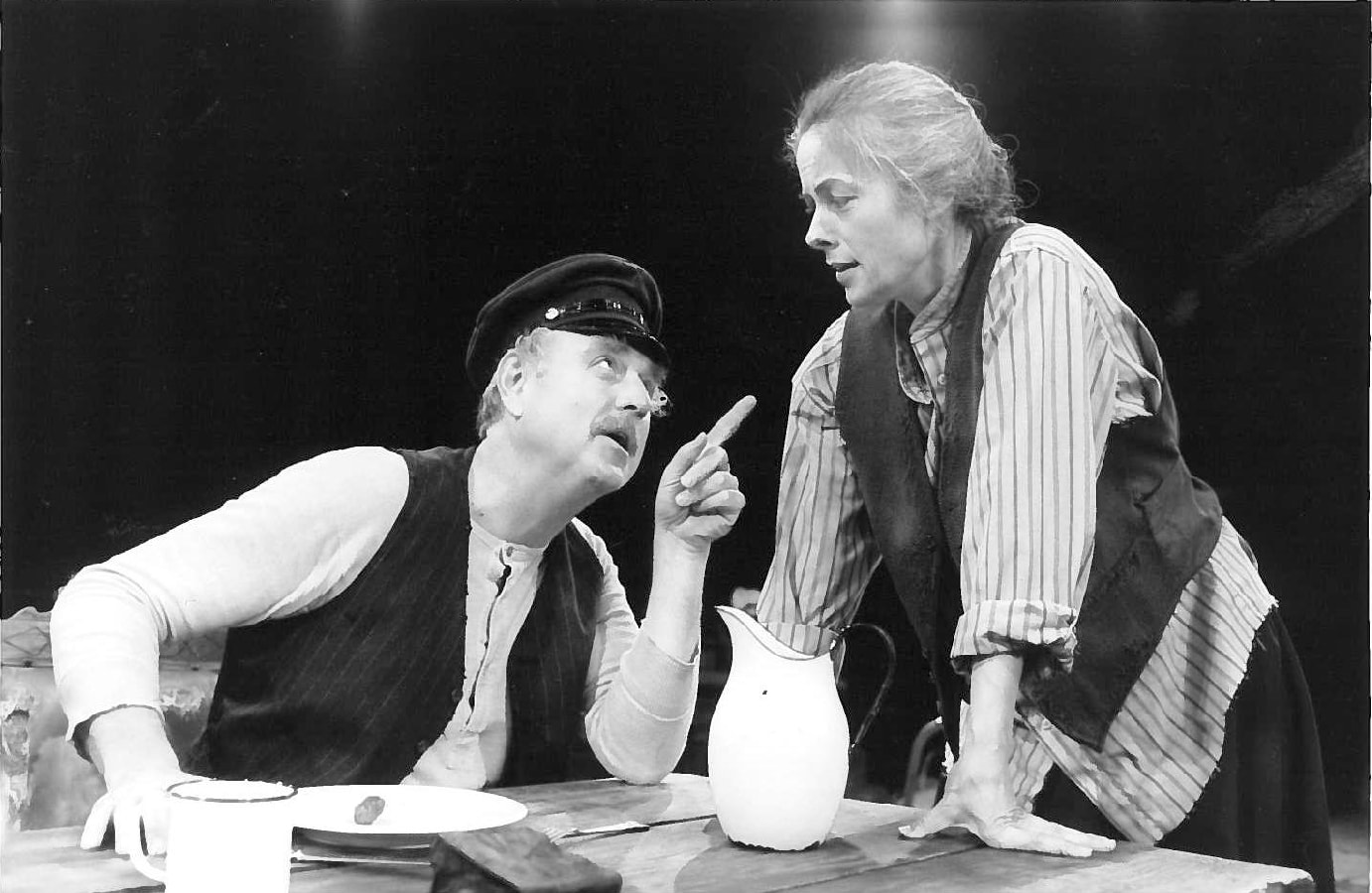

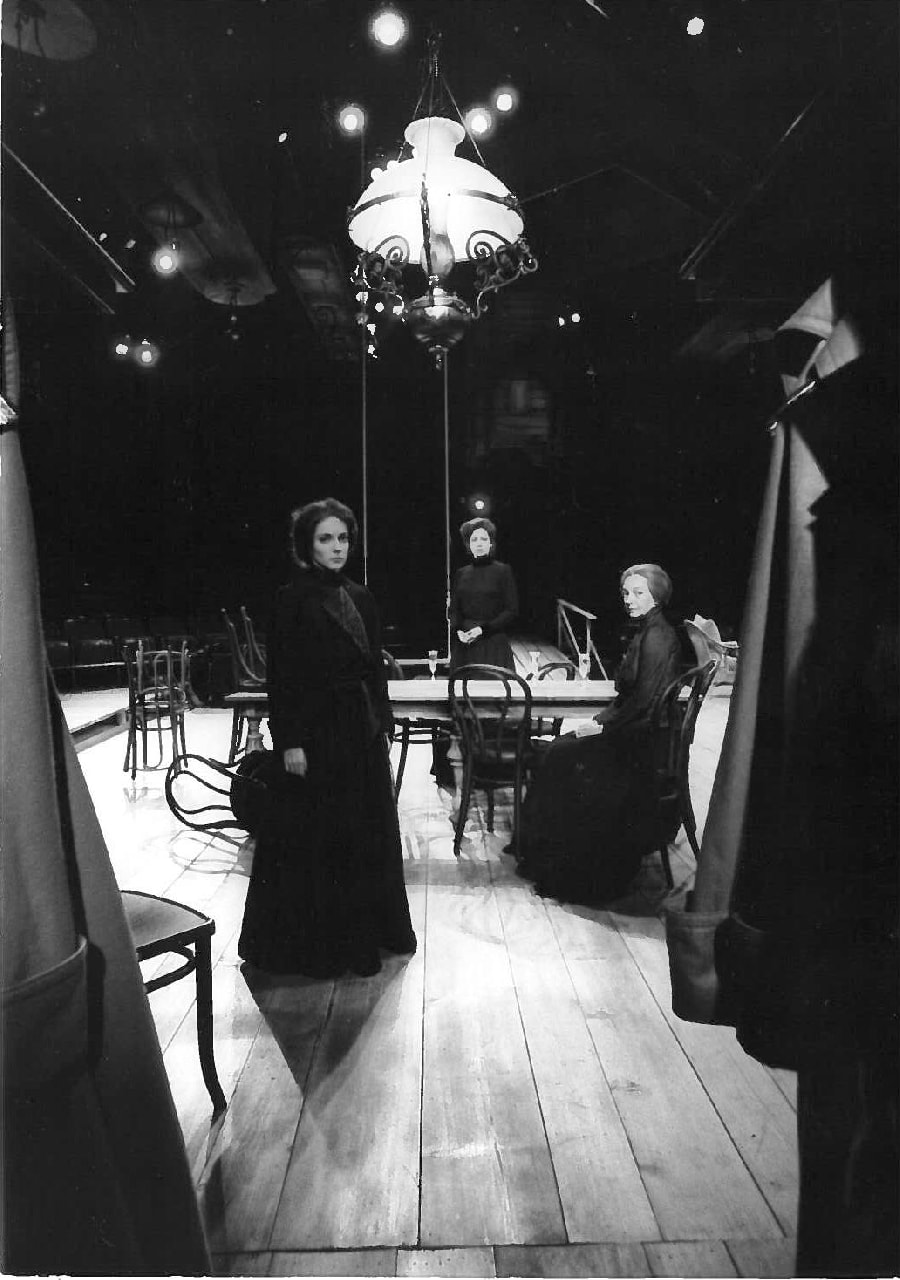

And I got to see Randy Danson fly. The first Chekhov play I ever saw was Zelda’s luminous production of The Three Sisters, in the early 1980s. The production was hilarious and heartbreaking, comforting and shocking. Alexander Okin’s environmental set was like a crazy, intricate country of its own. I happened to be sitting near the corner where Mark Hammer’s Chebutykin lazed and laughed and drank and cried in his little “room.” Unforgettable. I vividly remember Marilyn Caskey’s hilariously self-absorbed Natasha, Henry Strozier’s dutiful and sad Kulygin, Henry Stram’s tortured Andre, Halo Wines’s rock-of-Gibraltar Olga. But what I really remember is that Randy Danson flew. In the final act, when the soldiers are saying goodbye to the Prozorov family, Randy (as Masha) was quietly weeping in one corner of the vast Arena space, comforted by her sisters. Her life—or that part of it that held passionate possibility—seemed over. Now on the other side of the huge stage the solders came in for one last goodbye before moving to another camp. The stage got quiet as Stanley Anderson (Vershinin) stood looking across at the women. No one spoke. I didn’t breathe.

Suddenly Randy Danson was running—and I mean running—across the stage toward Anderson’s Vershinin. He was standing frozen. And while still far away from him—in my memory it’s half the stage, but how could that be true?—she leapt. She flew. And on the other end of that flight, Vershinin caught her in his arms. The world, my heart, time itself—all seemed to stop. When they embraced, I remember an audible, involuntary collective shout coming from the audience, a communal expression of joy and sadness and recognition. I’ve never seen anything like it in the theater, before or since. Maybe it was different from how I remember it, but hey, as Williams said: “The play is memory.”

She spent her life making people fly through the air, making sure there was someone to catch them, and making sure there were people to witness it all, so we could all live through it together.

Some years later, long after I didn’t fall into the dumpster, I got to work on The Three Sisters with Zelda and the brilliant Paul Walker with the Acting Company. I told Zelda about seeing that Arena production and its impact on me. She seemed moved that I’d been so taken with her Three Sisters. “Well, that’s what these great plays do for us. That’s what they’re here for.”

But someone has to understand those great plays, and take the care and effort and sweat and love to bring them forward. Somebody has to understand that they are essential, and that when we put them out there, and do it well, somehow the world is changed. Zelda knew. She famously said that she had started the Arena with an envelope full of index cards listing the people she knew in Washington, D.C., who might want to put on plays: actors, writers, designers, stage managers, possible patrons. She opened the envelope and got to work.

She spent her life making people fly through the air, making sure there was someone to catch them, and making sure there were people to witness it all, so we could all live through it together. Thanks to Zelda and a few other pioneers, the American theatre—the American national theatre—is busy doing its work, and making itself known all over the country in big venues and small, pushing and prodding and striving every day to reveal and celebrate the essential, aggravating, joyous, sad, exalted truth of our collective humanity. Zelda strove her whole life to illuminate that humanity. To paraphrase the great woman herself, that’s what she did for us. That’s what she was here for. And I’m so grateful to her for opening that envelope.

Andrew Weems, actor and teacher