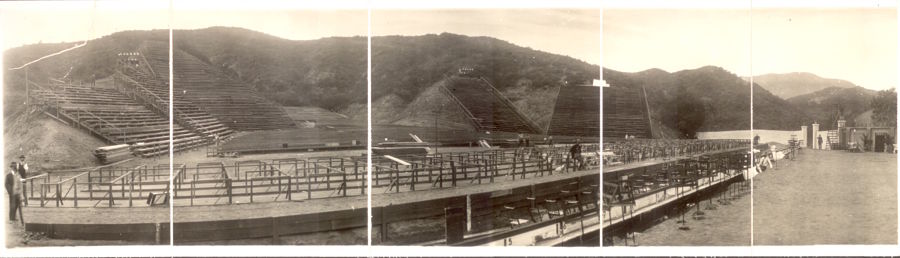

A cast of thousands—5,000, to be exact—gathered for Hollywood’s biggest production of the year. They were not there to make a movie, though. Instead, they were assembled for an even larger live audience of “thirty-five thousand persons, including notables from everywhere,” who had come to witness a “stupendous open-air” performance of Julius Caesar as part of the commemoration of the tercentenary of Shakespeare’s death in April of 1916. The event evoked the world of a romanticized Rome in every detail: Artisans created realistic representations of Roman buildings, performers dressed as Roman soldiers to take tickets from patrons, “sentries” guided audiences to their seats before standing guard on the hills, and a chorus of “fifty barbaric dancing girls” performed before the show. To ensure that elaborate battle sequences could take place, teams of laborers actually leveled off the earth on the surrounding hilltops. A Los Angeles Times headline boasted, “Los Angeles to Outdo World in Tribute to the Bard of Avon.”

This year’s celebrations in the U.S. marking the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death are part of a long history of Americans claiming the English playwright as central to our culture. Since the early 19th century, each generation has called upon Shakespeare to reinforce, define, or challenge existing norms, creating celebrations of the Bard that can be read as constructions of U.S. identity as much as explorations of the author’s work. In his great 1835 book Democracy in America, Alexis de Tocqueville remarked on Shakespeare’s popularity in the U.S., writing, “There is hardly a pioneer’s hut that does not contain a few odd volumes of Shakespeare. I remember that I read the feudal drama of Henry V for the first time in a log cabin.”

While there does not seem to have been outpouring of national sentiment for the 1816 bicentenary of his death, the 19th century did not lack for public celebrations of Shakespeare’s American-ness. In 1833 novelist James Fenimore Cooper observed: “Shakespeare is, of course, the great author of America, as he is of England, and I think he is quite as well relished here as there.” As historian Lawrence Levine has written, Shakespeare was widely performed on professional stages at the same time that he was playfully lampooned in parodies and minstrel shows that depended for their humor on a wide knowledge of his work. Shakespeare, in short, was America’s most popular playwright.

The sense that Shakespeare belonged in and to the U.S. grew throughout the 19th century. By 1864, the tercentenary of Shakespeare’s 1564 birth, the U.S. was all in on the commemoration business. Private literary clubs in Philadelphia, Cincinnati, and Boston celebrated Shakespeare by presenting scholarly papers, reading passages from the plays, or writing poetic odes and elegies. More public commemorations took place in Chicago, Detroit, and Lowell, Mass. The Century Club’s efforts to erect a statue of Shakespeare for New York’s Central Park (where it still stands at E. 66th St.) foundered until a group of prominent actors, including Edwin Booth, took charge of the effort. Funds were raised by an 1864 benefit production of Julius Caesar starring all the brothers of renowned Booth family: John Wilkes as Marc Antony, Edwin as Brutus, and Junius as Cassius. A year later John Wilkes Booth would paraphrase a line from Julius Caesar, “sic semper tyrannis” (“thus always to tyrants”), after murdering President Lincoln at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C.

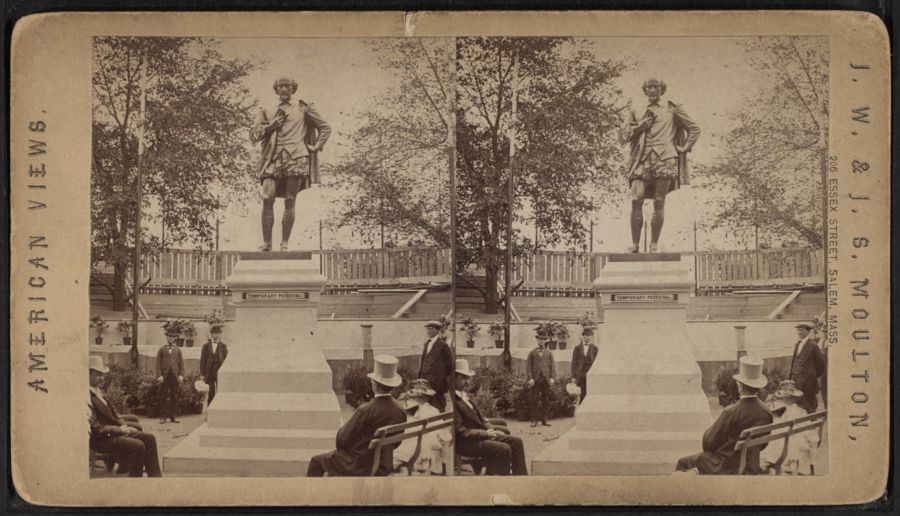

Edwin Booth also advised sculptor John Quincy Adams Ward on how Shakespeare should be dressed and laid the cornerstone when the statue was installed in 1872. At the commemoration event on Apr. 23, 1864, New York Judge Charles P. Daly highlighted the fact that the statue would be “executed by an American sculptor,” further distancing Shakespeare from his heritage by insisting that the dramatist “was a man who was too universal to be the property of any one age or nation.” The New York Times reported that the “desire is that the monument shall be purely American.” Historian Douglas Lanier has argued that the 1864 commemorations were a way of claiming “cultural sophistication on the international stage.”

Events on the national stage also made their presence felt. A tribute by a Boston resident, Rev. James Freeman Clarke, imagined a Shakespeare who was not only American but firmly on the Union side of the Civil War. (He was not alone, as Lanier points out; Oliver Wendell Holmes’s tercentenary ode similarly drafts Shakespeare for the Union side.) But the North did not have a monopoly on the 1864 commemorations; one Charleston, S.C., newspaper affirmed the South’s “rightful claim to our portion of the birthright in SHAKESPEARE.” The tercentenary celebrations of Shakespeare’s birth in 1864, then, both asserted American intellectual sophistication and staked out postwar national identities.

The 1916 celebrations were even more widespread, diverse, and extensive. Los Angeles may have wanted to “outdo” the world in its celebration of Shakespeare, but it was the New York presentation of Percy MacKaye’s Caliban by the Yellow Sands that has been best remembered by history. This masque, loosely based on Shakespeare’s The Tempest, involved 1,500 performers and was performed for 15,000 people a night. Like many of the commemorations in 1916, this New York showcase celebrated Shakespeare without performing any actual Shakespeare. As historian Margaret Knapp, who has studied the 1916 tercentenary extensively, puts it, “One of the most widely shared characteristics of the Tercentenary celebrations was that they were performances about Shakespeare, his work, and his world rather than performances of his work.”

In addition to the fact that few were up to the rigors of performing Shakespeare, there was also a widespread belief that much of his text was not appropriate for young audiences, and even many adult ones. It was an interesting paradox: Shakespeare’s work was universal but not necessarily suitable for all.

Dozens of cities and towns across the country joined New York and Los Angeles in the festivities. In Austin, 1,500 University of Texas students took part in a tercentenary celebration involving Morris dances, a Bartholomew Faire, and four productions by “players of national reputation.” A celebration in Fargo, N.D., featured eight Shakespearean plays, a 300-person chorus singing Elizabethan songs, a masque ball, and a huge pageant comprising “many floats made up of scenes from Shakespearean plays.” La Estrella, a Spanish-language newspaper in Las Cruces, N.M., advertised a celebration of “el trescentesimo aniversario de la muerte de Shakespeare” at New Mexico’s state college. Says Knapp, who has compiled an impressive list of the diverse ways Shakespeare’s death anniversary was marked in the U.S., “As might be expected, the anniversary was observed at schools and colleges, libraries, and museums. But celebratory events also took place in churches, department stores, symphony halls, women’s clubs, settlement houses, playgrounds, and even a Wall Street brokerage house. All across the United States there were Shakespeare concerts, recitals, and lectures. City fathers and other notables unveiled statues and memorial tablets, or toasted the Bard at lavish banquets. Students competed in Shakespeare oratory contests. Preachers extolled the Christian philosophy to be found in Shakespeare’s plays. Artists designed commemorative bookplates. Society weddings were planned around Elizabethan motifs. A Philadelphia astrologer contacted Shakespeare and Bacon on ‘the other side’ and reported that Shakespeare had indeed written the plays.”

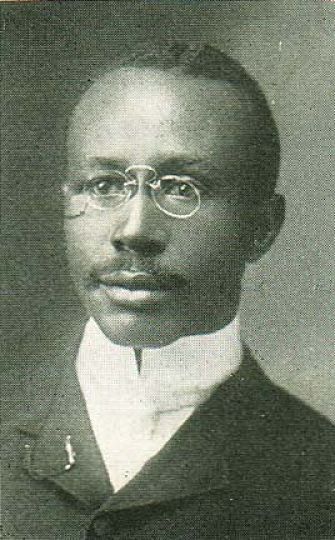

The Shakespeare tercentenary also provided an opportunity for African Americans to lay claim to Shakespeare and the cultural capital he provided. The Chicago Defender reported that in New York “twenty-five race societies, representing 8,000 members, have announced that they will take part in the citywide celebration of the Shakespearean tercentenary.” The newly recreated Lafayette Theatre in Harlem produced Othello with an all-black cast to celebrate the event. Edward Sterling Wright, who played the title role, told an audience before a performance, “The Negro people are Americans in the highest sense of the word…they are law-abiding, patriotic and as capable of being inspired by the plays of Shakespeare as any race in the world.” By performing Shakespeare and framing the author’s universality through a lens of racial justice, African Americans asserted their right to live in America as equals.

It’s clear that, as with the tercentenary of Shakespeare’s birth in 1864, the tercentenary of his death in 1916 was another opportunity to recreate Shakespeare in the image of the age’s anxieties, hopes, and struggles.

So, much as Shakespeare was pressed into service on the Union side of the Civil War, in 1916 he was seen through the lens of the ascendant Progressive movement, which believed that civic reform would transform the U.S. into a better, fairer country. The Drama League of America (DLA) was particularly active around these commemoration. Founded in 1910, the DLA was the most influential theatre organization of the 1910s and ’20s; within its first five years its membership grew to 100,000, with groups in almost every state. The organization’s mission was to “stimulate interest in the drama” and promote “worthy” plays. That the DLA would invest so much time and focus on commemorating Shakespeare should come as no surprise, as the much-vaunted “improving” qualities of his works fit their agenda perfectly.

The DLA invested much of its resources in providing leadership for educational activities. They appointed a “special committee” which produced a free, comprehensive 60-page guide for possible K-12 and “normal school” events to commemorate the tercentenary. With detailed descriptions, the guide offered multiple pageants, dances, and concert plans for everyone from small children to students well into their 20s.

The guide’s author, Percival Chubb, was a recent British immigrant who came to the U.S. because, as a lifelong utopian, he believed that society must be reconstructed “in accordance with the highest moral possibilities,” and he saw his new home as having the potential to achieve the goals he prized, above all “a spiritual alternative to an individualist society dominated by commercial values.” The guide he authored accordingly reflected Chubb’s investment in moral reform and improvement. “Merely as a matter of educational policy,” he wrote in the introduction, “there is an urgent need of the influence which should emanate from these festivals. They are needed to give new tone and quality to the literary, creative, dramatic, and recreational interests of young people—and, indeed, of the public generally.” All these efforts were to support the idea that, as the guide emphasized, “This is the great Shakespeare year; join the League in making it a great national renaissance.”

More troublingly, Shakespeare’s greatness was also taken as evidence of the superiority of whiteness. In Great Britain the tercentenary commemorations, occurring against the death and dislocation of World War I, set about to reaffirm community and continuity. But they also, as historian Coppelia Kahn notes, generated a story “of origin in which Shakespeare becomes the icon of a racial purity that lends itself to a sense of imperial mission.” That racist idea resonated across the Atlantic as well. While the U.S. had yet to enter the Great War, it was caught in its own national struggle over immigration policy. Since the 1880s immigration to the U.S. was no longer coming primarily from Northern and Western Europe but from Southern and Eastern Europe and Asia. Nativists, who saw this influx as a sign that whiteness was under threat, latched onto Shakespeare to make many of the same arguments their counterparts were making in Great Britain. Frederic Morgan Padelford, an English professor at the University of Washington in Seattle, for instance, explained to readers of The South Atlantic Quarterly that Shakespeare was a “Gothic” or “Teutonic” poet. “In him the spirit of the Gothic builders was reincarnate…the spirit of a race.” Thus was Shakespeare recast as the “universal” playwright—for non-immigrant white people.

Responses to non-white commemorations during the tercentenary only served to underscore the ways that Shakespeare was used to serve notions of white supremacy. Like James Hewlett, the great black Shakespearean from the 1820s, and like countless black actors since, the actors in 1916’s Harlem production of Othello were criticized for not speaking Shakespeare “correctly.” When the production toured to Philadelphia, The Philadelphia Inquirer complained about the actors’ “lack of the technique,” which led to “much slurring and disregard of the meter of the blank verse, and on the whole a too casual and commonplace and low-pitched performance.” And at the Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pa., an “all-American Indian” cast performed Shakespeare scenes in celebration of the tercentenary, and the Inquirer marveled at the “copper-colored Indian youths and maidens” whose tribute demonstrated “the hitherto unsuspected powers of dramatic characterization possessed by the aborigines.”

If in the 19th century, Shakespeare was seen as proof of growing literary and artistic sophistication in the U.S., in the 20th century he was used to demonstrate that the U.S. belonged in the first tier of nations. Two years after that lavish Julius Caesar in the Hollywood hills, the U.S. was mired in the global conflagration, an equal of its European allies and rivals. Now, 100 years later, as we celebrate the anniversary of his death with productions, Facebook memes, a hashtag (#Shakespeare400), and as he continues to top TCG’s list of most-produced authors, what are we trying to make Shakespeare say about us and our place in the world? The fault, dear readers, is not in the plays but in ourselves.