Blood on the Field

We work in a field covered in blood and it’s affecting my appetite. We often use the metaphor of a battleship to describe our theatres, usually while explaining why the change we desire hasn’t been enacted yet. In these conversations I then counter with a metaphor about farming or gardening. It’s easier to imagine our solutions when the metaphor posits theatres as living ecological systems.

August Wilson used the central metaphor of the ground: “I stand myself and my art squarely on the self-defining ground of the slave quarters and find the ground to be hallowed and made fertile by the blood and bones of the men and women who can be described as warriors on the cultural battlefield that affirmed their self-worth.”

Anniversaries are invitations to reflect. Twenty years after “The Ground on Which I Stand,” I survey this landscape of American theatre and feel disappointment at our failure to take Augusts Wilson’s suggestions, even as I acknowledge that his vision did not include all of me. His assessment of the field is as accurate today as it was then.

I feel impatience. We would be doing amazing things if we were not busy killing ourselves. I’m not speaking metaphorically. Wilson’s essay broke down the economic disparities of our field based in white supremacy with vicious, accurate poetry. I lack poetry. There is a quiet genocide happening in our country and we rarely speak about it directly.

Theatres are in the business of representation. Our bread and butter is reflecting and crafting culture. We say we value diversity instead of saying we will stop overvaluing white artists. We say we value inclusion instead saying will stop denying people of color or female artists access. We use metaphors. For so many years our theatres participated and supported white, patriarchal, heterosexist supremacy. This is done by appropriating, erasing, demonizing, and oppressing narratives and artists of all other cultures. This is what we have done.

I use “we” intentionally. As a queer female artist of color with a disability I get to the experience all the gaps, mistakes, and places where our large regional theatres reify toxic culture. I also get to own the responsibility of what we do together. POC artists invest in our organizations. We stand upon this ground made fertile, and denying this field is covered in blood is a double injury.

I find this metaphor of ground useful because it gestures towards the future. It is a group effort we are involved in. We are the ground, the blood, the seed, and grain we grow. We are the mortar, the pestle, and effort of the grind. This act of dismantling toxic, oppressive systems and biases fills the air with particulates, as in a grain silo. The atmosphere can be explosive, and we cannot underestimate the necessity and danger of this work. It’s how we create the flour we bake the bread of culture with. We have to eat or we will go hungry.

Claudia Alick, community producer, Oregon Shakespeare Festival

The Repeating Cycle

“The Ground on Which I Stand” is a seminal speech. Everyone should read it. Wilson spoke with such veracity to indict both the theatre and funding community for the history of resource exclusion experienced by black theatres. As a playwright, he could address these issues in ways that those of us who are responsible for institutions cannot do as candidly. Sadly, the speech remains totally germane to contemporary American theatre.

Having studied black theatre history, it’s undeniable to me that black companies have been subsidizing the American theatre for a long time. We invest in black artists, and predominantly white institutions come along and skim off the top. That goes unrecognized and unaddressed. It is still more lucrative for white producers to produce black work than for black producers to do so. If we were entrusted with funding that could actually capitalize our companies, our potential would be great. In many theatres of color, the caliber of the art is excellent. Wilson knew that and lamented the funding ceilings black companies hit. Twenty years ago, he’d seen funders invest heavily in predominantly white institutions to diversify their audiences and programming, and he demanded the same investment for black theatres. Sadly today the cycle is repeating itself. Diversity and inclusion efforts do not end up serving theatres of color; in fact, I think they often imperil them.

Wilson identified himself as a “race man.” That still means something to many of us. He was unwilling to separate his blackness from his artistry. There are some artists who say, “I don’t want to be seen as a black artist; I want to be seen as an artist first.” August was not about that. He shifted away from a Eurocentric paradigm. He always connected his work to the historic presence of black folks in this country—all the way back to the slave ships—and when you don’t allow people to forget that, a reckoning must happen. For me, there’s great power in Wilson saying that we won’t be denied our history, our voice, our temper, or our anger about what’s going on in the world, especially today, when we look at the way black life is valued, or not valued. We cannot allow ourselves, our plight, our pain, to be part of someone’s grant application. Our bodies are still not for rent.

Theatres of color are not about the advancement of individuals; they’re about the advancement of communities. That’s a very different mandate than most white theatres. You can hire to fulfill your diversity quota inside a predominantly white institution, but that doesn’t mean you’re uplifting the community.

Wilson knew that people would come down hard on him, that he would be called a separatist, and angry. I’ve been criticized in the same way; I’ve been told, “You’re not for the greater good.” Those people miss the point. We must attend to the history of race and economics in this country. The world of theatre is not immune. We are susceptible to the same prejudices and structures of privilege and inequity visible in every facet of American life. We must right these historic wrongs.

Sarah Bellamy, co-artistic director, Penumbra Theatre

The Ground Then, and Now

Witnessing August Wilson’s “The Ground on Which I Stand” speech 20 years ago was a revelation and a call to arms. Our celebrated black warrior was throwing down the gauntlet and making the case to the field that it was time for a truly inclusive American theatre to hold its wealthiest institutions to a higher standard of genuinely embracing the perspectives and stories of black and other non-white artists. I remember sensing that this speech was a historic moment that would catalyze a national movement to end the racial inequities in the American theatre. As the crowd rose to its feet cheering and applauding I felt, for a brief moment, real elation and hope.

As we all filed out of the McCarter Theatre in Princeton I suddenly found myself cornered in a vestibule off one of the exits by 8 or 9 artistic directors of LORT theatres who seemed visibly shaken, confused, in some cases quite annoyed. They fired unfiltered and impassioned questions at me like rounds of bullets from police cars at an unarmed black man in the streets of [insert city of your choice]. I agreed with August’s dislike for “colorblind” casting, by which we pretend an audience doesn’t see race. Different than August, though, was my directorial commitment to exploring “race-conscious” or multicultural casting which, with careful study, could enhance and deepen cultural and political perspectives in certain plays. But chief among my agreements with August’s address were with his keen and uncompromising observations about historic, institutionalized racial bias in funding, which favors many of our nation’s largest and most privileged theatre companies, and which excludes many of our theatres of color.

I was held beseiged by the outcries of denial, excuse-making, counterattacks, and interrogation of this impromptu throng for 20 minutes or so before I finally excused myself. This was only the beginning of a dialogue that still continues today. As I walked away I remember feeling that the improvised “caucuses” that many of us “artists of color” had held under the trees at these TCG conferences, starting back in the early days in the mid-1980s, had finally been laid at the feet of the white power brokers. Decades before Ta-Nehisi Coates wrote Between the World and Me, August uttered this in his keynote: “Assaults upon the body politic that demean and ridicule and depress the value and worth of our existence …must be met with a fierce and uncompromising defense.” When I recall August calling out “All God’s children got talent,” it rang in our souls like today’s clarion call: “Black Lives Matter!”

Twenty years later there is certainly some hope, as diverse plays and artists of color are finding their way onto more stages throughout the country bit by bit. Less encouraging are the stagnant numbers of women playwrights being produced and the gross underrepresentation of people of color in executive leadership positions in LORT theatres across our nation. Only when we truly stand our ground in these areas will real and lasting progress manifest.

Tim Bond, outgoing producing artistic director, Syracuse Stage

The Stages on Which We Do Not Stand

I am a white woman. I fully acknowledge whatever privilege that may afford me and recognize that I cannot begin to understand the lived experience about which August Wilson spoke in his seminal address. Yet his powerful words resonate with me more deeply than ever. Why? Because I am also an artist with a disability. Like Wilson and those who came before him, we bear the scars—physical, emotional, personal, professional, old, new, and yet to come—that compel us to fight for the opportunity to take our rightful place on that ground.

Wilson spoke passionately and forcefully about the need to break down the social and artistic barriers that American theatre tradition erected around black artists. His speech was a call to action, and while much progress has been made with respect to the representation of artists of color in our theatres, there is still much work to be done. Last month, a full 20 years later, Asian American artists in New York delivered their own powerful manifesto against yellowface and Orientalism, and transgender artists have begun to tell their stories accurately and authentically.

Why then do disabled artists and our stories remain virtually invisible on American stages? Physical access for audiences with disabilities has by and large become standard procedure, but the stages themselves remain predominantly off-limits—both literally and figuratively—to artists with disabilities, out of both ignorance and fear. And while the advancement of Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion initiatives across the country is to be applauded, those efforts typically focus on gender, race, and sexual orientation. Disability is often an afterthought, if it’s included at all—despite the fact that it crosses all lines and is a group anyone can join at any time. Disability still carries with it the stigma of being considered physically or intellectually “less than,” in society and on our stages. These perceptions and assumptions continue to go largely unchallenged, and thus unchanged. Until we are given, as Wilson suggests, “meaningful avenues to develop [our] talent and broadcast and disseminate ideas crucial to [our] growth,” disabled artists will continue to be denied the opportunity to tell both our stories and the universal stories that reflect our shared humanity.

Disabled artists are standing, sitting, walking, rolling, and signing on the shoulders of all those who have come before us. As Wilson said, “We want you to see us…We are not ashamed.” What will it take for the American theatre to recognize that all life is valuable, all experiences are human? Why must we continue to lurch forward, one underrepresented group at a time, reinventing the wheel every time? We are the theatre. We proudly declare that we are fearless, fierce visionaries, truth tellers. But as Oskar Eustis stated plainly in 2006 during an introduction to a performance of late playwright John Belluso’s unfinished last work, “If we do not accurately and authentically represent the lived experience of disability on our stages, we are lying.” Until we embrace the telling of all stories, with all bodies on every stage, we are holding a proverbial mirror up to nothing—falsely reflecting a world that has never really existed.

Christine Bruno, disability advocate, Alliance for Inclusion in the Arts

The Grind on Which I Live

Anyone who has the gravitas—cojones, really—to rattle the status quo about race, inclusion, and entitlement, and to challenge the American theatre to look at itself in the mirror, deserves my praise. But as an Asian American, a member of the LGBT community, and someone who has led a theatre of underrepresented voices and artists for the past 23 years, this speech still makes me feel invisible in the theatre community. To be fair, Mr. Wilson states at the beginning of his speech, “I do not have a mandate to speak for anyone,” and, “I speak only for myself and those who may think as I do.” And perhaps he did not want to give the normative mainstream the ability to lump us all together and write us off. I was not present at the conference where Mr. Wilson spoke, but I recall his speech 20 years ago sending shock waves through the theatre community, and I admit that East West Players has benefited from his remarks.

Was it perhaps the “white fragility” of 20 years ago that made this speech so controversial? To our newer members, was it “white fragility” that caused a stir once again at the TCG Conference in San Diego a few years ago when specific affinity groups for people of color came together for one 90-minute session?

Today, as I read Mr. Wilson’s words, my mind automatically edits the speech for today’s audience, today’s artist, today’s arts organization. We are a nation of individuals who choose not to be defined by any one category. We are a nation heading toward majority minority status by 2042. We are a nation where it is no longer a black-and-white issue (even if the 2016 Oscars failed to get the memo). The normative mainstream would push toward simplistic thinking and targeting, instead of the true complexity that is the American fabric. We no longer aspire to live in the mainstream because we now live in a many-stream society. We need to advance equity, access, and inclusion collectively as a field…now.

East West Players has been exploring these issues for the past 50 years—the economics of surviving as a theatre of color, non-traditional casting, season subscriptions—and we’re still here grinding it out every day.

Mr. Wilson’s speech didn’t refer to practices such as “yellowface,” which is happening more often today along with the whitewashing of Asian-specific roles so that non-Asian actors can play roles originally designated for Asians. But my community will no longer be invisible. Mr. Wilson states at the end, “The ground together: We have to do it together.” Let’s tell our stories in our most authentic and powerful voices.

I spoke to a leader of a major arts organization with one of the largest operating budgets in the country, who said, “We need to stay ahead of the game in everything we do because it’s too expensive to play catch-up.” Precisely. What are we waiting for?

Tim Dang, outgoing artistic director, East West Players

Multiplicity

I was in college, my sophomore year at NYU, when the article hit; I remember reading it, I guess in class. And then I went to see the debate with Robert Brustein, which was even at that point fascinating, bizarre—and fruitless. It was an important conversation but it didn’t really seem to go anywhere. They were both intractable in what their points were, and understandably so. It was eye-opening for me—a fascinating thing to have that kind of intellectual debate in Times Square and have so many theatre folks there.

I keep coming back to the speech itself. It comes up a lot in my teaching because of the colorblind casting issue, and the sense that he didn’t want to have white directors do his work—that only black directors could relate to the African-American experience in the U.S. Students seem to get really passionate about that, and feel real strongly about equity, diversity, and representation. What I teach are the opening five or six paragraphs, where he talks about the ground on which he stands, both the Western theatre and the black arts movement, and this idea of a dual identity, of multiple consciousnesses, multiple perspectives. I have my students read that and then make declarations about the ground on which they stand.

I’m a Puerto Rican kid who grew up in a Jewish neighborhood in an Irish-American part of New York. I grew up on hip-hop and professional wrestling. For a long time I had the sense that I had to divide them out, separate my high-culture and lower-culture interests. I didn’t speak Spanish but I felt beholden to that tradition. So reading that speech at that time in my life said to me: You have to declare who you are, where you’re from, and then you figure out, How does that translate into the art you’re going to create? My initial idea in following him was: He’s a proud African American, I should be that for Puerto Ricans, for Latinos. And there’s a part of me that’s that. But Latinos in the U.S. are fundamentally formed by dual or multiple consciousness. And the more time I spend with the speech, and I’m not sure if this is what he intended, but the way it speaks to me is: Just define all the traditions that define you, that make your voice unique, and be true to all those traditions in all their complexity.

I restarted a conversation like this when my son was born. Now I’m a dad, and probably 70 percent of my brain space is occupied by being a dad. My son is Puerto Rican and Filipino; I moved from Brooklyn to New Jersey. So I need to figure out how those new experiences interact with the old experiences.

We’re not all doing what August did, which was maybe most inspiring project of last 100 years, which was writing his Century Cycle. But even baked into that cycle was the idea of reinvention—of something different every decade. So whatever that is for us as writers, figure out how that fits into our experience.

Kristoffer Diaz, playwright

On Which I Stand

As August Wilson outlined in his speech “The Ground on Which I Stand,” work created by black artists has often fallen into one of two realms: Art “that is conceived and design[ed] to entertain white society, and art that feeds the spirit and celebrates the life of black Americans by designing its strategies for survival and prosperity.” The first time I encountered the work of August Wilson was in a college production of Fences. In watching the play, I saw how legacies of systemic racism impacted a family. I saw the ways that traumatized people enact their trauma on others. I saw disappointment, joy, love, and nuanced relationships. Most importantly, it was the first time I saw a family similar to my own depicted onstage.

Since Wilson’s speech in 1996, we have seen major strides in both theatre and other performing arts institutions. We have seen the emergence of black playwrights, actors, and directors who are creating innovative and crucial work. Where we’ve seen less progress is in how major regional theatres invest in this work. How these organizations allocate their resources has a direct effect on which stories are (and are not) told. This leads one to wonder what type of change can exist in the field where many black playwrights have to act as producers for their own work, while theatres continue to produce plays by European writers, albeit casting more people of color in the roles.

It is important to name that these dynamics are not happening in a vacuum: As much as our society pretends otherwise, race still plays a major factor in deciding the quality of life for people in this country. Consider this:

- Police officers murdered 305 black people in the U.S. in 2015

- Black people make approximately 43 of the incarcerated population in the U.S. despite comprising just 13% of the general population

- While black students make up 17 percent of all school-age youth, they account for 37 percent of school suspensions and 35 percent of all expulsions

We are still in a place as a society where the inherent value of black lives is questioned. It is for this reason that the statements Wilson raised in 1996 are still urgent. And this is why the equity work being conducted by so many theatres across the country is so crucial: It posits that marginalized people—those who experience severe systemic inequality—are just as integral to the health and sustainability of our theatres as our traditional patrons. As a part of my role as community engagement manager at California Shakespeare Theater, I have had the honor to see some amazing work taking place outside of our rehearsal rooms and apart from our stages. I have seen community members utilize theatre to tell their own stories in their own communities; I have seen performances that are created by and for marginalized communities. I have seen depictions of black life that look like my family and the families in my community.

As Wilson states, “We will not be denied our history.” Further, I would argue that we will not be denied the opportunity to craft the narratives for our future. It is simply a question of how theatres will support us in doing so.

Lisa Evans, associate director of artistic engagement, California Shakespeare Theater

How to Measure Success?

Reading the full speech in its entirety again—wow. As a black theatre artist, I was just so ignited. Has it really been 20 years? It’s like he just wrote it yesterday.

I think about two things in response. He cited the number of existing black theatres in the U.S. 20 years ago, and looking at the landscape—like he said then, there’s no shortage of black artists out there, but among institutions, there is a shortage, particularly at LORT theatres. That’s a situation that makes us have to stop and think: If it’s institutions that provide a home, provide space, provide development for artists, where are the black theatre institutions? Not only for artists but for audiences? During the Black Arts movement, they were talking about something like 400 black theatres—functioning theatres across the country. Now I can name maybe three. What is at play there? Is it the funding structure? What is the structural breakdown that is not allowing these institutions to thrive?

The other thing is his articulation of claiming of the black experience, not shying away from that in terms of telling our own stories. He focused then on colorblind casting, the buzzword of the day, and that hasn’t totally gone away, whether it’s revivals of Tennessee Williams or Shakespeare with black actors. And the question always is: What does that say, and what does that practice do to not necessarily validate a specific cultural expression?

When I first started reading the speech I felt: Wow, we really haven’t come that far. But there was something in me that forced me to check myself. I noticed that the theatre artists he cited were primarily men, and I started to think about the new crop of artists coming up; you look around and there are a lot of women’s voices. During the Black Arts movement and coming out of the ’70s and ’80s, you did not see as much representation of black women’s voices, certainly not as directors and even as playwrights. But now you look at something like Eclipsed on Broadway; there are examples that are really encouraging. There is a chipping away at systemic structures, but we still have a long way to go.

August touches on the subject of mainstream theatres, their structures and how they serve their audiences, and their model around subscriptions. Yes, it’s fantastic for Danai Gurira to get her play produced at the Public and then on Broadway. But who are the audiences that’s serving? When I start to think about the demographics, what is the percentage of African immigrant audiences in New York, let alone black audiences? I don’t think that’s who’s going to the Public. We have to look at how we define success for theatre artists. Is it just having a production? I don’t think so. August touches on this in his speech: It’s about having a conversation with your audience. So if it’s about having a conversation, how deep is that conversation? How multilayered is it? And who did you write the play for? Though the big institutions are funded and well-resourced, how well are they equipped to reach audiences who are not primarily wealthy, upper-middle-class people?

So we have to ask how we define success, and we have to push back, not just accept the crumbs, like, “Oh, I got a play up, hallelujah!” We need to challenge the existing institutions, challenge our funders about who they’re actually funding, and challenge our own standard of success to include who is coming to the theatre, what is the experience around artists and audience. This should become our standard of a successful experience. There’s a lot of challenging that should be happening across the board.

Kamilah Forbes, cofounding artistic director of Hi-ARTS, future executive producer of the Apollo Theater

Both Sides Now

It took me several days to read the speech again. Starting and stopping. Walking away from my computer and back again. The moments I stay, there are little activists running around in my chest giving each other high fives, and then my brain turns on, in momentary descent, and questions; my skin crawls when he names truths unchanged. I feel defeated and lifted at once. I pull my hair over my face and hold it there wondering when I have been able to speak my truth with this level of abandon. Have I? Other than in the corners of my mind? Even now, as I send in this reaction, can I tell my truth?

Most of his speech gets a resounding, “Hell, yes!” from me. As artists of color, we know. I feel seen when he talks about how our histories as black people inform our present. “We have a voice and we have a temper.” And every time I read, “As there is no idea that cannot be contained by black life,” I just want to run around the room shouting, “Yes! Yes! Yes!” I mean, the first time I read King Hedley II was the first time I saw my father’s rhythms on a page.

There is a challenge for me though, in being a mixed-race woman in 2016 reading the speech, and it is not a negative one. The challenge is, that while August and I shared a near-identical cultural mix, I consider myself to be black, white, and mixed. He considered himself to be black, which is absolutely true; I have no objection to that. His clarity around voice and culture was unwavering and gave us a narrative gift that, with this speech, changed the cultural and theatrical landscape. But for me, in 2016, when he says:

The problematic nature of the relationship between white and blacks has for too long led us astray from the fulfillment of our possibilities as a society. We stare at each other across a divide of economics and privilege that has become an encumbrance on black America’s ability to prosper and on the collective will and spirit of our national purpose.

I consider myself on both sides of that divide. As a writer, it forces me to ask myself: How are you going to write your own cultural truth, Khanisha? What does the rhythm of your voice look like on the page? Can I be a “race woman” like Wilson and Garvey were “race men”? When Wilson says race “is the largest, most identifiable, and most important part of our personality,” and my race exists in multiplicity, what will I do with the possibility in that? The ground on which I stand—I need sit with that idea, to think of who made me and who I can be. I want to write with the abandon of truth.

Khanisha Foster, associate artistic director of 2nd Story, ensemble member of Teatro Vista

Survival Is in Our DNA

In 1996, I was temporarily living in Atlanta and working as the marketing director for the National Black Arts Festival. The imminent birth of my daughter was consuming my every other waking moment. AT&T was a festival sponsor and gave us all cellular phones; we felt like the Jetsons. The AT&T folks went on and on about something call the web, and how it would change how we do everything. Yeah, sure, I thought. That’s the world for my grandkids. We now know that’s our world too.

Word traveled to Atlanta: Brother August got them white folks up north all riled up—he went Garvey on ’em (as in Marcus Garvey, the charismatic black separatist leader who preached Pan-Africanism). But in all honesty, I didn’t give much thought to the speech at that time, as my hands were full trying to market the festival, coping with becoming a first-time dad, and facing the unemployment that would loom at the festival’s end. But I have revisited the speech several times over my career. The power of its poetry, prose, and prophecy are at my fingertips through the use of that “web” thing the AT&T nerds hailed back in ’96. Today “The Ground on which I Stand” remains a powerful testament to August’s legacy and artistry as well as his penchant for social justice.

Throughout the speech August hammers on about economic disparity, and at one point notes that of the 66 LORT (League of Resident Theatres) theatres in existence at the time, only one could be described as a black theatre; that was Crossroads Theatre Company, where I currently serve as producting artistic director. Today that number is zero out of 72, as Crossroads is no longer a member of LORT, though I’m proud to say that our contract with Actors’ Equity references the LORT agreement, which means our salaries are in line with other members in the League. We are proud of that. But navigating the tricky nonprofit funding model is the elusive prize.

The disparities he highlighted regrettably remain today. I was hired as Crossroads’s executive director in the fall of 2007, and we all know what happened a year later—I don’t mean the election of our first African-American president but rather the worst economic crisis in over 80 years (nice timing, huh?). People often ask: How was Crossroads able to survive the Great Recession? Most theatres point to generous increases in philanthropic contributions from individuals to make up the difference. But in most theatres of color, a solid foundation of individual support based on large levels of philanthropy just doesn’t exist. (Why? The short answer: centuries of systemic racism, and the fact that theatres have been unsuccessful in tapping into a cohesive funding model the way black churches have.) I tell people that the crumbs that were usually reserved for us no longer existed. They just weren’t there.

But like us, several theatres of color across the country survived the Great Recession because survival is simply in our DNA. August touched on the power of the hallowed ground on which he stood, “on which I and my ancestors have toiled, and the ground of theatre on which my fellow artists and I have labored to bring forth its fruits, its daring and its sometimes lacerating, and often healing, truths.” We’ve survived hundreds of years of oppression, slavery, Jim Crow, even unprecedented and insidious attacks on our First Family—what was a little old Great Recession going to do that we hadn’t already experienced?

Well, for one, it could expose the true extent of the great economic divide in this country. Indeed, the disparities are worse than 1996, as noted in a recent keynote by Aaron Dworkin, MacArthur genius grantee, dean of University of Michigan’s School of Music, Theatre & Dance and founder of the superb Sphinx Organization, which teaches classical instruments to underprivileged kids. Dean Dworkin cited statistics from the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy, whose study “Fusing Arts, Culture and Social Change” indicated that total foundation funding equaled $22 billion, and that of that, arts and culture Grants were $2.3 billion–of which more than half went to organizations with budgets of $5 million or more. Among other things, that means that Crossroads and our fellow theatres of color don’t have budgets that large, so we don’t see a piece of the pie.

We need to focus on foundations. The Negro Ensemble Company established a remarkable two-decade span of some of the finest theatrical work of the century when it was buoyed by the Ford Foundation. To insure that culturally specific institutions don’t end up becoming a nostalgic relic like the Negro Leagues, foundations have the wherewithal to be game changers.

I’m hopeful for the future. August, too, concluded by saying, “I believe in the American theatre. I believe in its power to inform about the human condition. I believe in its power to heal. To hold the mirror as it were up to nature. To the truths we uncover to the truths we wrestle from uncertain and sometimes unyielding realities.”

Amen to that!

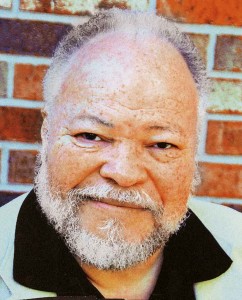

Marshall Jones, producing artistic director, Crossroads Theatre Company

Art and Practicality

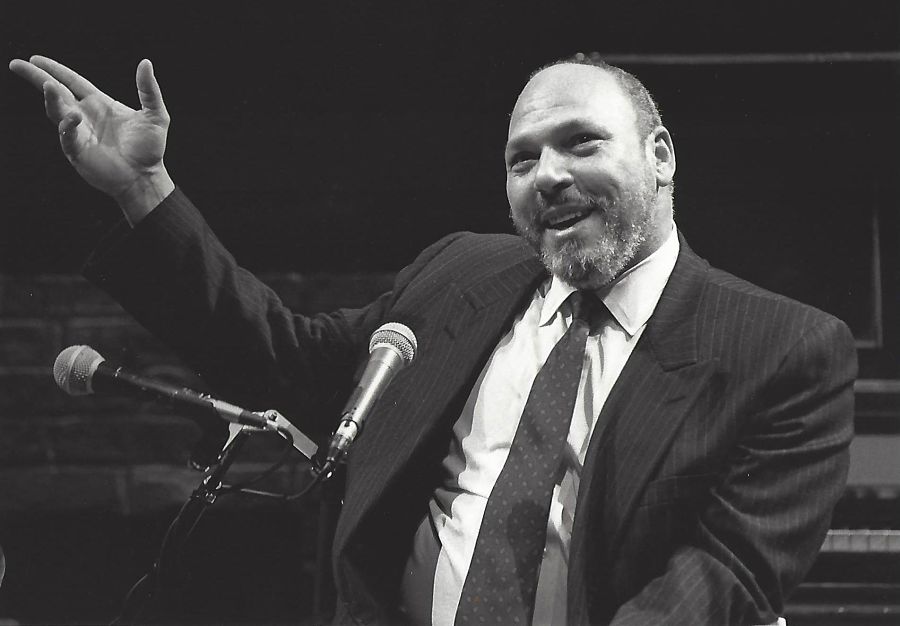

Out of all of us, August was the person who stood up and articulated a thesis statement about the state of the American theatre. It was very courageous of him; he didn’t have to do it, to stand up and say what was right and what was wrong, from his point of view. My question is: Who’s August Wilson now? Who is articulating the state of theatre in the way that he did?

I first met August when I was a TCG directing fellow at Center Stage, and I took people up to see Fences on Broadway. When I became associate artistic director of the Alliance Theatre in Atlanta in 1988, they had a play they wanted me to direct but I wasn’t interested. I said I’d met this great writer in New York named August Wilson, and he had a play that was about to go to Broadway, Joe Turner’s Come and Gone. I contacted him and he said, “You’re one of the only blacks working in theatre at that level; you can direct that play any time.” That’s how I ended up doing all 10 of his plays at the Alliance. The next year I was made artistic director, and every time I did one of his plays, he would come down.

When he delivered the speech, I had been artistic director for six years and we had produced four of his plays at that point. I was one of the few African Americans who was running a LORT theatre; George Wolfe was at the Public then. I had diversified the theatre’s mission statement and integrated the work that was on our stage. So I understood what he was saying. I disagreed with what he said about African Americans doing Shakespeare, but I didn’t see my disagreement as being against August. He was sticking the needle into places we needed to pay attention, and making the statement that it was a shame that the largest institutions were getting all the money and not putting money into supporting people of all colors. He was also talking about practical matters, about the financial end of it. It wasn’t just, “We can stand on the stage and act.” August was all about: Who’s getting a chance to feed their family?

We’ve come a little ways with some of this, but a lot of it has been circular. I love what’s been happening on Broadway this past season, with all these different kinds of diversity and different directors with different approaches. But I’m not sure what we’ll see in the coming years, if there’s a real commitment to that.

I agree with August in the sense of: Who is the custodian of the culture? If you’re a large institution like the Alliance, you are seen as a custodian of the culture, but a place like the Penumbra, which is also a custodian of culture, is not supported equally. At True Colors, where I am now, it’s still a challenge when it comes to the giving community to articulate: I’m the same artist I was when I worked at the Alliance. You have work really hard to get the respect; it’s just easier for them to give the money to an established theatre.

To my mind, it’s really about all 10 of his plays; all his plays are telling the same story. Whether you came to this country shackled and chained, or if you came here seeking cultural or religious freedom, or if you just came to seek a better life, America belongs to all of us. That’s what he was saying: Theatre should belong to all of us. And the money for theatre should go to all of us too.

Kenny Leon, artistic director, True Colors Theatre Company

Not Either/Or

Hearing August’s speech again 20 years later (and sitting in the same seat I sat in 20 years ago), I heard how beautifully written the speech was, how eloquent and galvanizing, as he called out his colleagues to hear the clear truth about the existence of the color line in the American theatre. August was in a position to make a brave stand, and he used the platform TCG offered him to deliver a groundbreaking speech (I’m using that term very deliberately, given the title of the speech).

However, there were three points I disagreed with him on that day, and I continue to disagree with him on today. One was his position on so-called colorblind or non-traditional casting—his saying that black actors should not be performing in plays by Arthur Miller or Shakespeare or any other writer who was not of African descent. I think artists should be able to create whatever they want to, limited only by the power of their craft and the size of their imaginations.

Second: He not only rightly called out the major theatres for not supporting black artists, calling instead for the support of African-American theatres. But I disagreed with the either/or paradigm he set up. I believe strongly that there is a need for race-specific and gender-specific theatres for artists to speak to their own, or be given a leg up, or produce their riskiest work. I would not have had my work produced 30 years ago without the Women’s Project. But it is not binary. Like many, I wanted to work at the Women’s Project and have my work produced in the mainstream institutional theatres and on Broadway. We need both gender- and race-specific theaters and inclusionary institutional theatres to have a healthy national theatre.

The third issue I found troubling was that August left women out of his speech. We were left completely out of the discourse, though women of color—all women, for that matter—were then rarely produced on major American stages.

Yet, even with all its flaws, this one speech changed the national conversation on race in the American theatre. It was important to passionately and eloquently make the point that most of the national theatres at that time were in fact segregated and not supporting work of color. Ever since this speech, the issue of inclusion is consistently part of the national conversation. And if you look at the numbers, August made a difference. Things are better now than they were then.

I’m forever grateful to my dear friend and colleague for his courageous words, and I was honored to walk arm and arm with him then, as I continue the struggle now. However, we must all remember that August’s speech was 20 years ago. The big question is: Who now will pick up the blood-stained banner?

Emily Mann, artistic director/resident playwright, McCarter Theatre Center

Black Arts Ascendant

In 1996 Eddie Gilbert, then artistic director of Pittsburgh Public Theatre, invited August to revisit an early play of his he’d written in the 1970s. August accepted. He and director Marion McClinton assembled a cast. During rehearsals of Jitney, August would from time to time ask a few actors about their experience with “non-traditional” casting. Paul Butler, Leland Gant, Anthony Chisholm, and I had worked the most in this capacity, and shared with him our various views. It was most often simply a way to have a job rather than be unemployed, but on occasion it was artistically fulfilling, even revelatory. We genuinely felt that the term “colorblind” was dishonest and insulting. It was best when no label at all was applied and you felt you were cast because of your audition.

I had been a company member for five years in St. Louis at the Rep in Webster Groves, and it was merely a condition of employment. It’s what an actor did. To be in at least five plays of a six-show season, you were going to be cast non-traditionally. It was no great social justice statement. More black professionals in every area of life, including other jobs in the theatre, would be more progressive than having actors of color doing roles in the plays that were traditionally produced. We had been schooled in the Black Arts movement and were making a living the best we could. Amiri Baraka had left footprints on all our paths.

August saw it differently. Major funding targeted to include diverse cultural voices went to traditional repertories only because of the change in casting. When he left us for a few days and returned after the TCG conference, we realized he had been forming his speech while immersed in the ’70s reworking Jitney. Upon reflection, I recall snatches of several of Baraka’s poems being shared, particularly a line from “Evil Nigger Waits for Lightnin’’: “who for the understanding intended, the love withheld.”

In 1996 August found it necessary to reflect upon the origins of the Black Arts movement from more than 20 years prior. Now 20 years hence, the irreversible sweep of history has brought us Barack Hussein Obama exiting the White House. The continued outpouring of minority artists has not lowered but raised the standards, and Hamilton is in the heights. The Signature Theatre, a playwrights’ theatre, is also an all audience-accessible theatre because of its ticket prices. Every theatre now has some form of “diversity” outreach. Playwrights of every background are produced on and off Broadway and throughout the regionals.

August would love all this. But how long before the theatres for minority voices he wanted to nurture are integrated out of existence? Without the support of our own patrons, entrepreneurs, and artists, could black theatre could slowly go the way of Negro League baseball? Amiri told me in his last year that he was now a “revolutionary optimist.” And optimism is a revolutionary act only when you act on it.

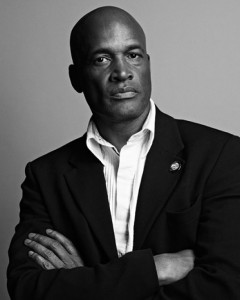

Stephen McKinley Henderson, actor

Holding Up Our Own Bar

Before live-streaming and “tweet seats,” I recall huddling next to my kitchen radio tuned into NPR for what felt like a welterweight match of the world. It was the winter of 1997, and playwright August Wilson was going toe to toe and head to head with director Robert Brustein at a hothouse Town Hall in New York City; the Pittsburgh lefty southpaw versus the Great White Hope eager to shed white guilt faster than a silk robe falling off a boxer’s back!

Oh, man, it was heaven: Wilson’s elegant articulation dissecting the institution of American theatre, with Brustein no less articulate; nor did any corner come off as shrill. It was muscular, robust, and—for young theatre minds like mine, still idealistic about our regional theatre—a plain fucking mind-blower. I didn’t pretend to understand the nuances of the debate, but rereading Wilson’s landmark “The Ground on Which I Stand,” I can see the storm that brewed. I miss his restlessness and his brilliant intellect.

His Century Cycle, his prose—there was no equal. Yet Wilson could be a patient teacher for we Culture Clash students; luckily he liked our work. While he was in rehearsals and rewrites for Gem of the Ocean he slunk into Chavez Ravine at the Mark Taper Forum not once but twice! We knew he was intensely busy, but over a Scotch he told me he may have to “borrow” our “abuela with a shotgun” beat. A year later, true to his word, Phylicia Rashad held a shotgun like a Mexican! I had borrowed the image from stories of my grandmother from the mountains of New Mexico who ran off mafiosi looking for my bootlegging grandfather already doing a “nickel” at Leavenworth. We regaled him with such stories over dinner in Seattle.

Our brand of docutheatre may not have fit neatly into his argument; I suppose we were riding the multicultural wave that made Brustien bristle. But our stories were real and characters raw and true, and he appreciated that we dealt with race front and center.

Following Wilson’s example, I began to refer to myself as a “race man.” I was riding coattails I had no business reaching for—but I’m glad I did.

I would learn later the realities of subscriber-based audiences, donors, critics, even technicians, who articulate and determine a bar of excellence that has little to do with how good we are or not. We can only continue to challenge these notions of excellence and hold up our own bar. Some major critics to this day do not possess the yardstick to properly review our work, or even care to. They tolerate African-American work but when arriving at us, there is fatigue: Fuck the Mexicans. (Trump is not the only one saying this!)

These are things I am only beginning to understand now, thanks to a genius with a blue-collar work ethic guided by principles I abide by today: I’m still yearning to be planted in our creative spiritual core, unwilling to enthrall ourselves in colorblind casting of the classics we may or may not have any business doing. I have nothing to prove in that arena, only the colonial ghosts yet to shake off my back.

Richard Montoya, playwright/performer with Culture Clash

New Ground on Old Land

Five hundred words (which is what I was asked to write) couldn’t even capture a burp of this profound essay on which many of my writing principles have been based. August Wilson gave us language to define what we feel when we instinctively share our cultural aesthetics in art, and are then told to “colorblind” ourselves in order to satisfy a privileged majority that feels uncomfortable with their privilege and everyone else’s race. What do we call this conundrum? August Wilson calls it “maiming.” He declared that we artists of African descent will not be maimed.

I further declare that neither will we as women. Neither will we as children of immigrants and multiple languages and patois and Kreyol. We have been given permission by this essay not to be squashed in our cultural specificities. We actors do not have to accept that being cast in a role originally written as a white character somehow means we have shattered a glass ceiling rather than potentially being culturally neutered.

The ground that August has built, and upon which I now create art, demands that we do not ignore cultural difference. That our common humanity exists not in neutralizing everyone’s unique expressions and practices, but by embracing it all. This ground challenges those who walk timidly on eggshells and feel confronted by phrases like “black theatre” and maybe even reject being identified by their culture. It says that “black theatre” exists and is a thriving practice deserving recognition.

While I further acknowledge that not all black people practice black culture, nor is black culture accessible only to black people, it no less exists. There is music and food and expression and language and rhythm that has been specifically cultivated by a people and passed on through generations. None of us is obligated to it. There are no prerequisites for all people of African descent. But a culture exists that is commonly practiced, and like all forms of humanity, it has value in the American theatre.

We revisit this speech during a wave of national political unrest. The time to agitate these uncomfortable circumstances and inspire social change and collective human understanding is now. Theatre has always been at the forefront of new ideas and innovative ways of thinking. It is the bedrock of human connection and healing. It has a huge responsibility to be the leader of evolved thinking. We can no longer practice the same marginalization in theatre that is destroying our national humanity. Theatre practitioners cannot be as fearful as broken Americans who seek to “make America great again” by silencing people of color and reverting to cultural, racial, and gender oppression. We have to make our audiences as balanced as the art we seek to produce.

The new ground on which I stand is built with compassion and fearlessness. We don’t have time to apologize for our truths. We only have time to speak, evolve, and agitate complacency so that theatre becomes not just another vestibule for white privilege and supremacy but a true mecca for all people.

Dominique Morisseau, playwright

Up From Violence and Empire

Theatre has traditionally been and continues to be an unbalanced and unjust arena for artists of color and women.

When I mentioned the 20th anniversary of Wilson’s speech to an academic theatre colleague, he queried, “Do you agree or disagree with Wilson?” How strange. It was like being asked if one agrees with freedom or the right to vote. Too many liberal elite theatre professionals and academics think themselves so progressive, that prejudice and racism are not possible within their ranks. Such self-righteous superiority is a main target of Wilson’s speech and antithetical to the artistry of the theatre.

Everyone is prejudiced. People form opinions about “others,” including ideas with which they have little or no experience or information; it’s how they face the world. Prejudice becomes racism when people cling to prejudices after being presented with contradictions to their timeworn beliefs. As the world becomes more interconnected, those who believe themselves educated are faced with a growing body of evidence and information that contradicts old “ideas,” some held by theatre and entertainment professionals. As the presidential campaign demonstrates, crowds are ready to turn racist hate into power by leveraging bigotry into populist mandates. That is fascism. The “civilized” world has fought many wars over fascism and is poised to repeat this history.

The United States was built on the labor of dark-skinned people, more than 10 million of them enslaved. Land was taken through war; a government was created to conduct ethnic cleansing; more than 15 million indigenous people were murdered, tortured, and raped, while well-funded governmental systems attempted to annihilate their culture. Race-based violence and actions are core American practices.

That legacy bears fruit daily. Race too often defines one’s opportunities in the world. Data sets accurately predict children’s life trajectories born into particular zip codes, known in academic circles as a “preschool-to-prison pipeline.” The impact of American-style violence, beyond the particulars of the gun debate, lies in empire-building, high suicide rates among military service personnel, and the mass incarceration of our citizenry. The social ills resulting from this violence are appalling. We people of color must band together with women and the LGBTQ community to confront this history of violence.

While some of Wilson’s predictions of progress have come to pass, much is still the same in terms of resources and opportunities. His speech is clearly from a black perspective, arguing for black aesthetics that are equal in “excellence” to “white” definitions. While I absolutely agree with his desire, I believe we are beyond black/white debates.

It is good to celebrate “the mountaintop” and it is good to remember “The Ground On Which I Stand.” It is also good to remember both were once Indian land. I love August Wilson’s plays. While revering his actions and his words, we must simultaneously embrace today’s agents of change in American theatre. Let’s read and rejoice in Wilson—then buy tickets to new productions. While celebrating Lin- Manuel Miranda, lets also delve into the works of Dominique Morisseau, Marcus Gardley, Lynn Nottage, Luis Alfaro, Qui Nguyen, David Henry Hwang, Chey Yew and even some Native American playwrights. Can we write plays? You bet your ass we do.

Randy Reinholz, co-creator and producing artistic director of Native Voices at the Autry

Lift Every Voice

August Wilson’s speech, “The Ground on Which I Stand,” resonated with me upon my first hearing in how Wilson was able to articulate his vision of a beautiful marriage between life and art. Life for a black man with dreams in America is a very specific experience. Wilson came up weaving the American fabric that exists today in his social influence with the Black Power movement of the ’60s and his artistic influence of writing the Century Cycle. I find his passion and emphasis on race enlightening; he was not interested in dismissing color, a fact of life in America, for the sake of comfort. He was more interested in acknowledging, accepting, and celebrating that difference. Wilson was redefining the black man as he relates to society by building a better conversation, shifting the linguistic environment around black theatre in America. Common ground was the only way to achieve this.

Wilson points out that while we both decorate our houses, we do it differently, for we have different values. We both offer guests refreshment albeit with different foods, for we have different culinary values. We have different social values. We practice different manners. But we must work to find common ground, to develop a view that doesn’t make the distance between races so vast. Because it isn’t.

Wilson asserts that our common ground is American theatre as we build it: a new fabric in progress, where every voice can speak in its purest form, with its purest heart, with the clearest understanding and definition of self. But for the success of a “ground together,” the assault on black theatre must cease, just as “other assaults upon our presence and our history cannot continue.” About mid-speech Wilson reminds his audience that “black theatre in America is alive…it is vibrant…it is vital”; this has become a pillar of strength for me. As a young woman of color experiencing similar social shifts in 2016, I can only hope to live art and life as seamlessly as Wilson. Inseparable. Indistinguishable.

Ireon Roach, winner of the 2016 August Wilson Monologue Competition

At the Stream

In today’s shocking climate of intolerance, with federal judges subject to accusations of bias because of their race, where hatred creates violence, language continues to feed the ignorant. I cite, as Mr. Wilson does, Webster’s Third New International Dictionary (with my added italics):

MINORITY: a number or amount that is less than half of a total; a group of people who are different from the larger group in a country, area, etc., in some way (such as race or religion)

MAJORITY: a number that is greater than half of a total; a number of votes that is more than half of the total number

The usage of “less” and “different” versus “greater” and “more” insinuates one is less than the other. Rejection of this language is a necessary step in repositioning our community’s psyche to embrace the fact that we are the mainstream. To define:

MAINSTREAM: a prevailing current or direction of activity or influence

The mainstream. We all drink of the same water, at the same river.

Let it be clear: No one is mainstreaming us. We mainstream ourselves. We are a prevailing current, and we determine the speed and the direction where the stream runs.

A month ago, the Latino Theatre Commons, a national movement that uses a commons-based approach to transform the narrative of the American theatre, met in Seattle to organize the local Northwest Latino theatre community and to encourage their participation in the Commons. We heard of their decades-long legacy of bringing theatre to their community. Maria Irene Fornes found an artistic home and directed many of her works there. Ruben Sierra was an artistic connector and invigorated the theatrical community with his talents. Jose Gonzalez founded the Milagro Theatre Company in Portland and it remains vibrant today. From Tucson to Dallas, from Chicago to Los Angeles, from Washington, D.C., to Miami, from New York City to San Francisco, Latino theatre stands on the shoulders of a 50-year-old legacy of activism by telling our stories on our stages. The Commons has reversed the dominant narrative by acknowledging our history and unifying us to create a powerful group that champions equity through advocacy, art-making, convening and scholarship.

In the summer of 2015, we came together at De Paul University and 12 of our playwrights were featured in a festival. Eighteen of our theatres committed to producing plays by these playwrights by 2017. We are doing this for ourselves and plans are in the works for the next five years.

In 1996, Wilson told artists of color that we needed to “alter our relationship to the society and to alter the shared expectations of ourselves.” In 2016, Latino artists in the Commons, as well as so many of our theatre workers, are in the process of changing that relationship. We embrace those allies that champion this cause and we work on multiple levels to create equity.

No more fighting to be at the table. That table will come to us. No more victimization when we face closed doors. We’ll open the doors ourselves. Now we have our own table and it’s a big one. We have our own seat, and it’s the driver’s seat. So what are we waiting for? We’ll give you a ride.

Diane Rodriguez, director/writer/performer, member of National Council on the Arts

Doing It for Ourselves

I remember August Wilson’s speech very vividly, as well as the controversy that it created. I thought it was an amazing speech from one of our great American writers, and I appreciated the courage of someone who was so accepted in the establishment holding an uncompromising mirror up to it. In all honesty, I didn’t expect any major changes at the LORT theaters to come about because of the speech, and ultimately, I do not think enough change has happened since. I do believe, however, that Wilson’s speech reached out to artists of color and said to them: You are not alone. Wilson proclaimed to us that what we were feeling about how the American theatre viewed theatres of color was not in our minds but was in fact a lived reality for many.

Wilson’s speech ignited a spark within artists of color that has not been extinguished. Two years prior to Wilson’s speech, I left a prestigious position at a LORT theatre, in part because of many of the issues Wilson spoke about, and committed myself to providing a space for Latino artists and all artists of color—a space where our work would not be relegated to perpetual development and where we could be at the helm of our own storytelling.

Taking a cue from Wilson, the ground on which artists of color stand today is unabashedly their own, as they have moved out of the margins and created their own movements, no longer waiting to be recognized or validated by the establishment. We are telling our own stories, honoring our ancestors, staging our histories unapologetically and with our own frameworks. Our audiences are growing; tired of not seeing themselves on regional stages, they seek out artists and companies that reflect their realities. At this point, radical change to the institution of the American theatre is the only way to ensure its survival. Demographics are rapidly changing in the United States; our streets are alive with vivid colors, languages, and experiences, but our stages are not always so beautifully realized. While diversity has become a buzzword and community engagement is all the rage, our artists still struggle to find work at the LORT level, and ugly stereotypes still mar the casting and hiring process for many.

I wholeheartedly agree with Wilson when he stated, “To pursue our cultural expression does not separate us. We are not separatists…We are Americans trying to fulfill our talents. We are not the servants at the party.” Unfortunately, many artists of color still feel like “servants at the party,” and it has become my life’s work to throw our own parties where everyone has a seat at the table. The ground on which I stand is beautiful, it is powerful, and it runs deep, a rich network of roots connecting me to my cultural and artistic ancestors. As we honor Wilson’s candor and bravery, may we always continue to fuel the spark he ignited within us.

In the words of our indigenous ancestors: “Do not forget that, above all, you have come from someone, that you are descended from someone, that you were born by the grace of someone; that you are both the spine and the offspring of our ancestors, of those who came before us, and of those who have gone on to live in the great beyond.”

Jose Luis Valenzuela, artistic director, Los Angeles Theatre Center