Twenty years before the Internet would become routinely captivated by debates about representation, diversity, identity politics, and racial equity in culture—decades before the Vida Count or #OscarsSoWhite—there was “The Ground on Which I Stand.” August Wilson’s landmark 1996 speech dynamited the hardened crust of assumptions about what late-20th-century racial progress looked like, allowing subterranean tensions and conflicts to bubble up, and over, the surface. It also placed theatre—that often under-loved and under-discussed art form—at the forefront of a national conversation about integration, nationalism, assimilation, and power. For months the speech would be widely published, then hotly debated, then become the subject of a verbal sparring match at the Town Hall in New York City between Wilson and critic Robert Brustein that made the front page of The New York Times. Looking back from today, you can clearly see the moment when presumed certainties—such as the value of “colorblindness” or Benetton-style “multiculturalism”—fractured.

Before the explosion, however, before a word of the speech was written or delivered, there was just an idea: Invite August Wilson to speak at the 1996 Theatre Communications Group conference in Princeton, N.J. TCG was at that point in the midst of several transitions. For one, John Sullivan had taken over leadership from Peter Zeisler. And among those planning the conference, there was a spirit of wanting—needing—to shake things up. Recalled Sullivan, “I asked Ken Brecher, who had been an associate of mine at the Taper [in Los Angeles], and his wife, Rebecca Rickman, to come in and help develop the conference. One of the first things Ken and Rebecca did was put on the table that we should invite August. It was obviously a great idea.”

Sullivan said he wanted to address underexplored tensions in the field, specifically around “what we called multiculturalism. We just had to talk about it. People who had not been a part of the TCG world were pushing and wanting access, so this seemed like a great opportunity to get the issues on the table.”

At that point, the New York run of Wilson’s Seven Guitars had just finished, and Wilson was starting on a kind of sequel, King Hedley II, as well as tinkering with his earlier Jitney. Speaking engagements had become part of his career as a public intellectual. As Wilson’s widow, Constanza Romero, recalled, “August was asked to speak quite a bit at the time. He would speak at graduations or at events in Seattle,” where the couple lived and she still lives. “People wanted to know what he thought about in terms of himself and his country. He always brought up the topic of being more self-determining as African Americans. He always spoke up for having more funds and more resources available to black people.”

But he had never explicitly addressed theatre, his chosen art form, in these conversations. When TCG invited him to do just that, he did not take the opportunity lightly. Writing the speech entailed weaving together a number of Wilsonian themes and ideas, and also directly responding to the context of the time. In 1996, the predominant efforts to diversify the American theatre and increase racial equality revolved around foundations providing funding incentives to members of the League of Resident Theatres to program diverse work and do “nontraditional” casting. Actors’ Equity Association had been pushing the latter idea for a decade, holding the first Non-traditional Casting Symposium in 1986 and establishing the Non-traditional Casting Project, which, according to its website, “maintains thousands of active files to facilitate the casting of minorities and actors with disabilities with Equity’s active support.”

Although he had helped found a black theatre in Pittsburgh and developed many of his early works at St. Paul, Minn.’s Penumbra Theatre, the bulk of Wilson’s career as a major American playwright took place within the LORT system. As Romero put it, “As part of the process of developing his plays, he would go from one repertory theatre to another. As he traveled through these different theatres, he was welcomed by everybody, but he never thought that this was somewhere where he could, as he put it, ‘hang his hat.’ He never felt like he was at home. He always felt like a guest. An important guest, but a guest nonetheless.”

Romero said that Wilson had been asking why black people didn’t have a theatre. “Of course there was Crossroads [in New Jersey], but where were the theatres where the resources and the staff were black, not just the receptionist? He saw the inequality of resources, the difficulty black artists faced when developing a theatre of their own. It was a frustration—and a need—that had been growing in him.”

That urgency comes through palpably in the speech itself, first delivered as the TCG keynote on June 26, 1996. It is an oration as complicated, occasionally contradictory, thematically thorny, and lyrically stunning as any he wrote for the many African-American men (and a few women) seeking the dignity of self-determination in his plays. Reading it, you can hear Herald Loomis and Floyd “Schoolboy” Barton; you can sense the powerful imagery that would become the “City of Bones” in Gem of the Ocean a few years later; you are witness to the imagination that created Berniece’s piano. As in the best of Wilson’s monologues, you can also hear the speaker working to define himself for the audience.

Today, all that many people remember about the speech is that Wilson came out strongly opposed to “nontraditional” or “colorblind” casting. It’s true that he did, at length and with passion. Here is some of what he had to say about the issue:

Colorblind casting is an aberrant idea that has never had any validity other than as a tool of the Cultural Imperialists who view their American culture, rooted in the icons of European culture, as beyond reproach in its perfection…To mount an all-black production of a Death of a Salesman or any other play conceived for white actors as an investigation of the human condition through the specifics of white culture is to deny us our own humanity, our own history, and the need to make our own investigations from the cultural ground on which we stand as black Americans. It is an assault on our presence, and our difficult but honorable history in America; and it is an insult to our intelligence, our playwrights, and our many and varied contributions to the society and the world at large.

But to limit the conversation about “The Ground on Which I Stand” to the issue of colorblind casting—that is, to the issue that most directly challenged white theatres at the time—is to ignore the full scope and radicalism of Wilson’s vision, and the ways in which the speech was as much about Wilson defining himself as it was about the American theatre. Reading the speech today, it’s clear that Wilson is in part saying that, though the majority of his career was spent within white LORT theatres, he was not of them—he was not a “crossover artist” who, as he put it, “slate[s] their material for white consumption.” Instead, as he wrote, “I stand myself and my art squarely on the self-defining ground of the slave quarters, and find the ground to be hallowed and made fertile by the blood and bones of the men and woman who can be described as warriors on the cultural battlefield that affirmed their self-worth. As there is no idea that cannot be contained by black life, these men and women found themselves to be sufficient and secure in their art and their instruction.”

Self-defining. It’s a concept that comes up again and again in the speech; it is, in many ways, the speech’s mission. It means not only that Wilson claims the right to define himself; he is also speaking for what he feels black theatre artists require to define themselves. What they needed most, he concluded, was their own artistic homes.

As Ruben Santiago-Hudson, a frequent collaborator and friend of the playwright, put it recently, “He and I always had dialogue about the need to forge our own identity and our own theatres and not need and depend on other people to give us opportunities to do our art. He said: ‘Let’s take care of ourselves. Let us be the catalysts of our future and our images. Let us be the custodians of our culture, of when it’s dispersed, how it’s dispersed, when it’s disseminated, and to whom.’”

To that end, Wilson’s critique extended beyond casting practices to the influence of funders and critics. The former he castigated for spending diversity money to incentivize programming of works by people of color in white theatres and the casting of people of color in traditionally white roles in the classics, rather than supporting the work of theatres of color. The latter—represented by The New Republic’s Robert Brustein, whom he singled out by name in his speech—he criticized for mistaking the white experience as “universal,” then using that criterion as a pseudo-objective benchmark for evaluating all art. The universal—the experience of what he called “love, honor, duty, betrayal”—could be found, he said, as easily in the particularities of “a Mississippi farmer” as in those of “an English baron.” Wilson believed that white and black artists “can meet on the common ground of theatre as a field of work and endeavor. But we cannot meet on the common ground of experience.”

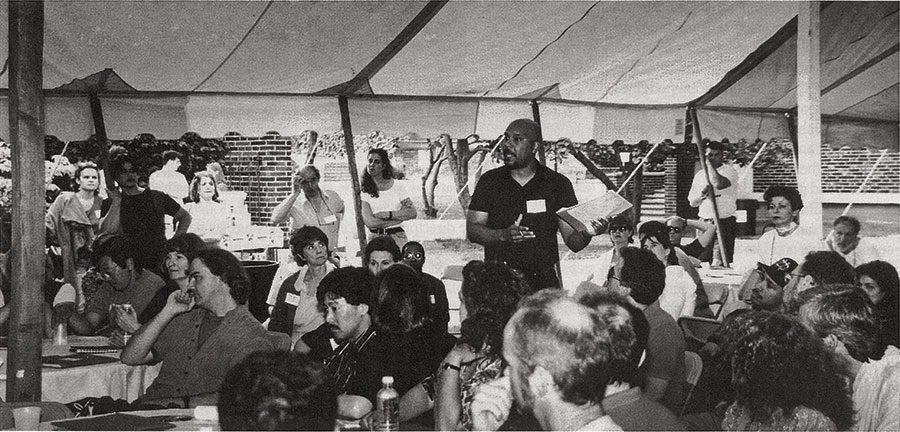

The response to the speech at the conference was immediate—and explosive. Recalled director Benny Sato Ambush, “It blew the conference up. Everything about the normal schedule took a back seat to the overwhelming importance of reacting and responding to that speech. You could feel everybody being set off while he was talking.” Soon Ambush and others at the conference organized a series of meetings under a big tent to discuss the speech. “I think we were there for three hours, going at it, 50 or 60 people, each getting a chance to talk about the speech.”

While everyone at the conference seemed to register the shock waves of the speech, Romero said Wilson wasn’t surprised. “He knew it was going to be big,” she said. “He knew the weight of it. I read different versions of it, and I would say, ‘Are you sure you want to say that?’ He would revise it and say the same thing again, but even more firmly! He was like that. That was part of his backbone—the way he believed in his ideas more than anyone else.”

It didn’t stop there. For months after the conference, American Theatre magazine featured responses to the speech from everyone from performance scholar Richard Schechner (“The interactions among the world’s marvelously promiscuous people are myriad and…to be celebrated”) to playwright Eduardo Machado (“The full expression of talent is anarchistic, the real enemy of institutions, society, capitalism, showbiz, and political correctness”) to Penumbra founder Lou Bellamy (“Most of the stereotypical constructs under which my community labors are created by white institutions”).

“The Ground on Which I Stand” clearly brought to the surface conflicts that had simmered underground for years: “Colorblind” casting, levels of funding, the way black artists were treated at LORT theatres, whether art could be evaluated without bias, and more. Reading over the chorus of responses today, you can see assumptions being shaken, turned over, reexamined: Is there such a thing as a theatre for everyone? And if so, were the LORT theatres of the time that thing? Could a majority-white theatre do justice to black works? And, perhaps the most provocative and fundamental question: What is American culture?

The most forceful response to the speech came from the very critic Wilson had called out by name: Brustein. Writing in the pages of American Theatre, Brustein took Wilson to task for speaking for what he called “the language of self-segregation.” Perceiving in Wilson an “ambivalent sense of American identity,” Brustein responded to Wilson’s nationalism with what we would now call an appeal to a “post-racial” consensus. Reflecting on the controversy via email, Brustein returned to this theme: “What I objected to in his speech was the element of self-segregation. If this had been followed we would have lost many great Shakespearean performances.”

In what would become a familiar refrain years later during the Obama presidency, Brustein ended his American Theatre essay with a plea for colorblindness, pegged to Martin Luther King Jr.’s oft-misunderstood quote about judging people not by the color of their skin but by the content of their character. Brustein also wrote that he himself was “not at all certain anymore what constitutes a ‘black’ or ‘white’ theatre,” and added that Wilson “is displaying a failure of memory. I hesitate to say a failure of gratitude,” pointing out that all of Wilson’s plays were developed and produced within the ostensibly white LORT theatres he was speaking against.

All of the various dynamics that would come to shape our ongoing national conversation about race in the ensuing decades—and not only in the theatre—were here. In Brustein’s argument that earmarking funding for specifically black theatres amounted to a “reverse form of the old politics of division,” we can see echoes of the fight over affirmative action in hiring and higher education that led Chief Justice John Roberts to declare that “the way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race.” In Wilson’s insistence that “doing a black play or allowing blacks to have roles not written for them does not change the nature of the institution or its mission” because “our visitor pass expires,” we can hear the arguments over the slow progress of racial justice even during the tenure of the nation’s first black president.

And Brustein’s assertion that Wilson’s vision of black identity proceeds “as though everyone with the same skin color had the same culture and history” reads today as if it presages our now-daily Twitter spats about the meaning of race and the value (or lack thereof) of identity politics.

After all, there’s no getting around it: Identity politics are at the heart of what Wilson was demanding, and of the kind of theatre of which he was dreaming. As he would later write in response to Brustein, “To have a theatre that promotes the values of black Americans, our hard-won survival and prosperity, that addresses ways of life that are peculiar to us, that investigates our personalities and social intercourse and philosophical thought, is not to be outside of the American theatre or Western theatre any more than Ibsen and Chekhov’s explorations of Norwegian and Russian culture make them outsiders—or David Mamet’s insightful and provocative explorations of white American culture make him an outsider.”

Wilson’s response in American Theatre did not revisit the colorblind-casting issue. Indeed, one of the great misperceptions of the time appears to be that that issue was what he cared most about. As Romero put it, “It wasn’t so much that he didn’t want to have people working—like black people working in Shakespeare, for example. He was more asking, Why can’t we have our own plays? Yes, these black actors are being hired, and they’re able to pay their student loans and their mortgages, but why can’t there be something like the O’Neill Center but for black artists, so that these black actors can be representing their own race onstage?”

Said TCG’s Sullivan, “I think the two men had different points of view that reflected issues that were much more than racial. August was calling for a culture that was more horizontal and less vertical—a culture that recognized the need to empower creativity in every community, that the standard of our art-making needed to be the breadth of our ability to empower creativity.” Brustein, Sullivan said, “comes from a different place, a sort of vertical, rigorous hierarchy of thought as a place where one develops one’s standards. It’s not that either is wrong. It’s that those are very different worldviews.”

In their back and forth, Wilson’s and Brustein’s very different worldviews kept getting further apart. It was writer/performer Anna Deavere Smith who first had the idea of trying to put them back together.

“A reporter called and asked me to talk about it, and I declined to comment because I hadn’t spoken to either Mr. Wilson or Mr. Brustein,” Smith recalled. When she finally called each of them, she learned that neither man had spoken to the other through the whole controversy. “I asked: If I could get them in a room together, would they talk? They said yes, if I would moderate it.” At the time, Smith had a residency at NYU, and initially tried to craft an event that would feature both men discussing their viewpoints for a small gathering of students.

“I turned it over to the office of that institute at NYU, and the administrative assistant in the office was in charge of the logistics,” Smith recalled. And there the idea almost died: The assistant “called Mr. Brustein ‘Mr. Bernstein’ on the phone, and he refused to participate because she got his name wrong. I thought, Well, this is unfortunate. So I called TCG.”

Soon, what Smith envisioned as a small conversation in front of students ballooned to a sold-out, heavily promoted event. The choice of venue—Town Hall—changed everything. Steven Samuels, who worked at TCG at the time and helped produce the event, recalled, “Tickets were not available. It was an invited audience. We had to issue the invitations to these extraordinary cultural figures, and then figure out how to seat people. It was worse than a big wedding.”

Said Ambush, who also worked on the event, “It was the hottest ticket in town. There were practically street fights outside to get in. It was absolutely packed to the rafters. People were willing to sell their firstborn to get in.”

For Smith, this is when the event’s nature changed for the worse.

“I knew I was in trouble when a P.R. person called me up and was talking about it like it was a boxing match,” Smith said. “There were bets that Wilson would take it. I was horrified. At the time, 20 years ago, I still believed that you could have substantive conversation. Even now when we talk about race, we use that word, conversation, but it’s pretty impossible—it’s not the right word. Conversation is something that happens between a few people; it can’t really happen in a country or in a city or at a big event.”

The pugilistic metaphor was apt, in a way. Said Samuels, “Mr. Wilson had a punching bag in the basement near his writer’s room. He was a boxer to a certain extent. I don’t know that he ever fought, but he was like a boxer.” Romero said that while Wilson was never literally a boxer, he was a huge boxing fan, and that when she thinks of her late husband, “One of the images I always have of August Wilson is him being alone in a boxing ring. That was August Wilson’s life. He was always in his own private boxing ring. Sometimes he hit the canvas, but he stood back up. He felt like a warrior. He loved boxing as a metaphor for many things.” August Wilson, in other words, came ready to fight for his beliefs.

You can still hear an abbreviated version of the Wilson-Brustein debate on NPR’s website; it was archived for “Fresh Air.” Even in the excerpt you can hear the precise moment when any hope that Smith’s original goal—that the two men could reach beyond their own strong points of view to have “what we could call a conversation”—becomes impossible. It’s immediately after both men have delivered their opening remarks, and Brustein, referencing A Raisin in the Sun, says to Wilson, “I have nothing but the utmost respect for what you said. I think you have probably the best mind of the 17th century.” Brustein chuckles a little under his breath as the audience emits scattered laughter, then hisses.

Ambush primarily remembers the two men talking past each other. “They weren’t quite face to face,” Ambush said. “They were on the stage together, but the conversation didn’t so much go back and forth to each other. It was rather that one would state a position to the crowd, the other would state a position to the crowd. I was hoping that they would turn in and go at it; I don’t recall that really happening much. It may be because I don’t think they were necessarily warm and fuzzy about each other.”

According to Sullivan, “Anna brought a great deal of subtlety to try to get them to engage. They came loaded for bear and shot everything they could. The energy was very, very masculine.”

“When the argument started to go south, neither Mr. Brustein nor Mr. Wilson seemed particularly interested in budging,” Smith recalled. “People wanted a big theatrical splash; I don’t think they were looking for consensus or ways for this to move forward. It became something that stands in history, but I think we had an opportunity to do something that was better, deeper, more useful.” Instead, she said, “When I went backstage in the break before we had questions, the fever pitch of the people back there—you would’ve thought I was in a boxing match, like I was thrust into a chair and water was shoved in my throat and I was told what to do because I was missing the drama of the event.”

During that short break, Samuels, Smith, and Ambush worked to select questions from the audience that would be asked during the second half. “I felt that if the questions were live, it would be chaos and their quality would be questionable,” Samuels said. “Instead the audience wrote down questions and we had this team of runners that would gather them and bring them to us. We didn’t have enough time to go through them all; Anna went back upstairs with the first set and then we stayed downstairs for another 15 minutes going through them, and then I had to walk onstage at Town Hall to hand Anna the second set of cards and then slink away. I’m glad I was wearing a three-piece suit.”

Given the difficulty of getting the opponents to give ground, Smith said, “It was up to the audience to move the conversation.” One place it swiftly moved is beyond simply dichotomies of black and white, as an audience member asked, for instance, if it was okay for gay people to play straight characters; the speakers demurred from answering. Then the following exchange happened:

ANNA DEAVERE SMITH [reading an audience member’s question]: I am an actor of mixed cultural heritage. My mother is Jewish, of Austrian-Polish descent. My father is black, mixed with a bit of Scots, Irish, and Native American Indian. Both of them were highly involved in CORE in the 1960s, and my father is currently president of a chapter of the NAACP. I was raised in a predominantly Chicano neighborhood in Los Angeles [laughter, applause]. Where does someone with my type of background fit in the American theatre?

[Whooping, applause.]

WILSON: I have just sat here and said in no uncertain terms that I make my own definitions. However that person wants to define themselves, fine. If they define themselves as black, then I think, personally, that it is wrong for them to participate in the theatre acting as someone other than as a black person onstage.

At the debate’s end, Smith asked both individuals to talk about what they learned that night; Brustein said that he was surprised to find that Wilson was “a teddy bear” (Wilson was not amused). Both agreed on one thing: that foundations shouldn’t be using funding incentives to get LORT theatres to program work by people of color. Left unsaid was that this “agreement” papered over one of their fundamental differences—namely, that Brustein felt that funding should go to the “best” work, and that we were sufficiently evolved as a society that questions of racial bias need not be taken into consideration—that a naturally occurring multicultural theatre absent discrimination was possible, if not already extant. Wilson, meanwhile, felt that only black artists and companies could do justice to black characters, black writers, and the black experience, and that he would prefer that black actors only play black characters written by black writers.

According to Romero, Wilson was happy with how the event turned out because “he voiced what needed to be voiced.” Still, many were disappointed. Writing in The New York Times, Frank Rich—who echoed the sports analogy by saying the night “promised to be the intellectual version of extreme fighting”—pronounced it little more than “two humorless and often petty egomaniacs intransigently reiterat[ing] their familiar positions…The sad fact is that more and more Americans would rather see (and financially support) a stage sitcom like Beauty Shop (on the chitlin touring circuit) or proliferating stage spectacles like Cats (on the Broadway touring circuit) than anything either Mr. Wilson or Mr. Brustein produces. Both men narcissistically fiddle (and bicker) while the world of serious culture they share burns.” In a sense this objection presaged another debate from our last decade about whether racial justice could be attacked on its own, or whether there were other issues (to take an example from the current election, class) that should be considered alongside it. In a recent email, Brustein wrote that he feels “somewhat misrepresented regarding August Wilson,” with whom he said he became “rather closer in his final years.”

Looking back, it’s hard to gauge fully the impact of “The Ground on Which I Stand.” Smith suggested some possible measures: “Are there more artistic directors of color now than then? Are there more managing directors of color now? What is the status of diversity in the major nonprofit theatres in this country? How many producing directors, how many people who run the scene shop? Have we delivered an increased number—not just actors—but playwrights, designers, directors, people behind the scenes? To what extent do theatre artists of color feel welcome and supported by the major theatres?”

For his part, Santiago-Hudson said that “very little has changed. What is encouraging to me now is that, while there are only a few artistic directors who aren’t white, there are still more white artistic directors who get it, who say, ‘Hey, this shit’s got to change,’ and they’re trying to change it. But if you look at the really major nonprofits, the ones that produce on Broadway—I mean, what work are they doing?”

Samuels thinks we should look at individuals to see evidence of change. “There’s someone who was 15, 16, 17 years old at the time, and this moment was a seminal moment in their development. That’s where you can find hope of meaningful change.” Meanwhile, he said, “The structures are almost impossible to shift, and I don’t see much change there at all.”

Perhaps it is too much to expect radical change of funding priorities, boards, and artistic directors to issue from one speech, a passel of letters to the editor, and a highly publicized debate. Instead, perhaps, we should look again at the speech itself, and at what August Wilson felt called to do:

I have come here today to make a testimony, to talk about the ground on which I stand and all the many grounds on which I and my ancestors have toiled, and the ground of theatre on which my fellow artists and I have labored to bring forth its fruits, its daring and its sometimes lacerating, and often healing, truths.

Isaac Butler is a freelance arts writer based in New York City.