On March 14, Soho Rep in New York City held its annual gala. This year’s honoree was actor/writer/director, and Soho Rep board member, Tim Blake Nelson. With the theatre’s permission, we are reproducing an excerpt of his comments from that evening here.

The question naturally arises, with all that’s wrong in the world, and the array of not-for-profits organized against each challenge: Why give money and time to a tiny theatre in lower Manhattan—which is to say, to an increasingly esoteric enterprise in an esoteric neighborhood?

Now that question rides its way to us on a complex sentence—the first and conditional clause of which I’ll return to in a moment, because to my mind, many of the predicaments we’re in socially are in part caused by fundamental changes in our attitudes toward art. And in accepting this honor tonight I want to speak briefly not only in defense of what we do at places like Soho Rep, but in full-throated advocacy of it.

I started out in theatre with no abiding intention of acting in so many films, and certainly little hope of getting to make them as a writer/director. Within the theatre, my four years of conservatory training—after four years studying classics at college—was the most conservative available. My wife Lisa, whom I met at Juilliard nearly 30 years ago, called our school the Catholic Church. And though our time there well predated the references, she meant of the Ratzinger variety, not the Pope Francis. The training centered on Shaw, Chekhov, the Jacobeans, and most of all Shakespeare. Cameras and screenplays simply weren’t allowed in the building, and the works of living playwrights were slotted in carefully, with stern admonitions as to the inherent and lethal corruptions of any writer still drawing breath.

It might surprise you, given my devotion to new work, to hear that for me this was fantastic training. Put succinctly, the idea was: “If you can act Shakespeare and Chekhov and Shaw, you can handle any material in any medium.” Our oldest son now studies music composition in Juilliard’s pre-college [program], and the paradigm is largely the same: Become learned and articulate foundationally in advance of pushing the art form forward.

The best avant-garde theatre work, from well before the term’s early 20th-century origins when applied to art—and I mean from Plautus in ancient Roman theatre, who referenced the works of the Greek playwright Menander when he brought street Latin onto the stage, through Shakespeare’s astonishing invented vocabulary and innate sense of structure that found roots in Sophocles and Aristotle, all the way through Ionesco in the early stages of the last century, to Sam Sheppard, John Guare, and Suzan-Lori Parks toward the end of it—there has been vital attention paid to foundational traditions. The works therefore were, and are, articulate, lucid, captivating, timeless, and utterly immediate, even while manifesting constant reference to the greatness of the form.

And when groundbreaking work took place, whether in theatre or other artistic media, its power had phenomenal meaning. Think, if you will, of early abstract painting and the audacity at the beginning of the 20th century, and just over 50 years after the first photograph, to put a non-representational work of art before a public. Or of the premiere of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring at the Theatre des Champs Elysees in 1913, where rioting broke out in an audience unprepared and half-baited by the dissonance of the music and the percussive assault of Nijinksy’s choreography.

Now I’m not saying this relevance has abated entirely. In our own we have works like Hamilton, and I’d also argue The Book of Mormon, that break through and matter because they inflect a mainstream sensibility with conceits that are utterly new. But such work has become far too exceptional in the popular sphere, even while folks like us can seek it out and find extreme versions of it in venues such as the one we’re here to celebrate tonight: Soho Rep.

Generally, and here I get to sound even older than my 51 years, we have a culture less and less interested in a patient, educated, and learned approach to what it is we do. This permeates everything. I have no conceptual issue with Times Square as a far safer place than when I arrived here way back in 1986. But go to 42nd and Broadway and look up: We’re in a time devoid of nuance, subtlety, patience, and any sort of real aesthetic space.

Now before you groan, I have no doubt that some sententious, over-inflated, and insufferable boob like me has been decrying the deficiencies of his age like this in every decade. What was Times Square like during the era of bebop or the ’60s or the ’80s? Surely there were billboards and noise aplenty. And that’s true. But was there ever so much of it, and were the debasements ever so manifold, repetitive, and mind- numbing? Because so much of what we want can now be delivered so quickly, so cheaply, and so prodigiously, our experiences can be endless, yet our memories of each far more fleeting. We have virtually everything, but actually less and less that truly lasts. It’s just too gorgeously easy to hold our attention before that next bigger and immediate distraction. Am I a consumer of much of this? Absolutely. In spite of best efforts, has my attention span been reduced? My sensitivity dulled? My rude and caustic impatience sharpened? I believe so.

And it hits me most of all in the field in which I work. With the admitted exception of premium television and some modern literature, so much of what we consume popularly as narrative these days takes for granted not our imagination and intelligence, but our stupidity. So much so that when I take my 11-year-old to a mythological or historical film, we can’t go 10 minutes without him enumerating the inaccuracies, and those not in service of heightened drama or narrative efficiency, but because the real events have been deemed too complex to handle.

Spectacle replaces meaning, noise erases nuance. Intricate and challenging melodies are replaced with ever more simplistic chords. We have less and less patience for anything more.

Now the easy argument against this is that it’s inherently elitist. Only the wealthy and highly educated would seem to have the wherewithal either to appreciate or create work in the spirit I describe. But I choose not to accept this insult both to artist and audience, which brings us to tonight. I’d challenge anyone in this room to name a successful production at Soho Rep that one would need a fancy education or a wealthy upbringing to appreciate.

To be groundbreaking and esoteric, novel and intoxicating, is the opposite of exclusion and insult. It’s an act of inclusion and love.

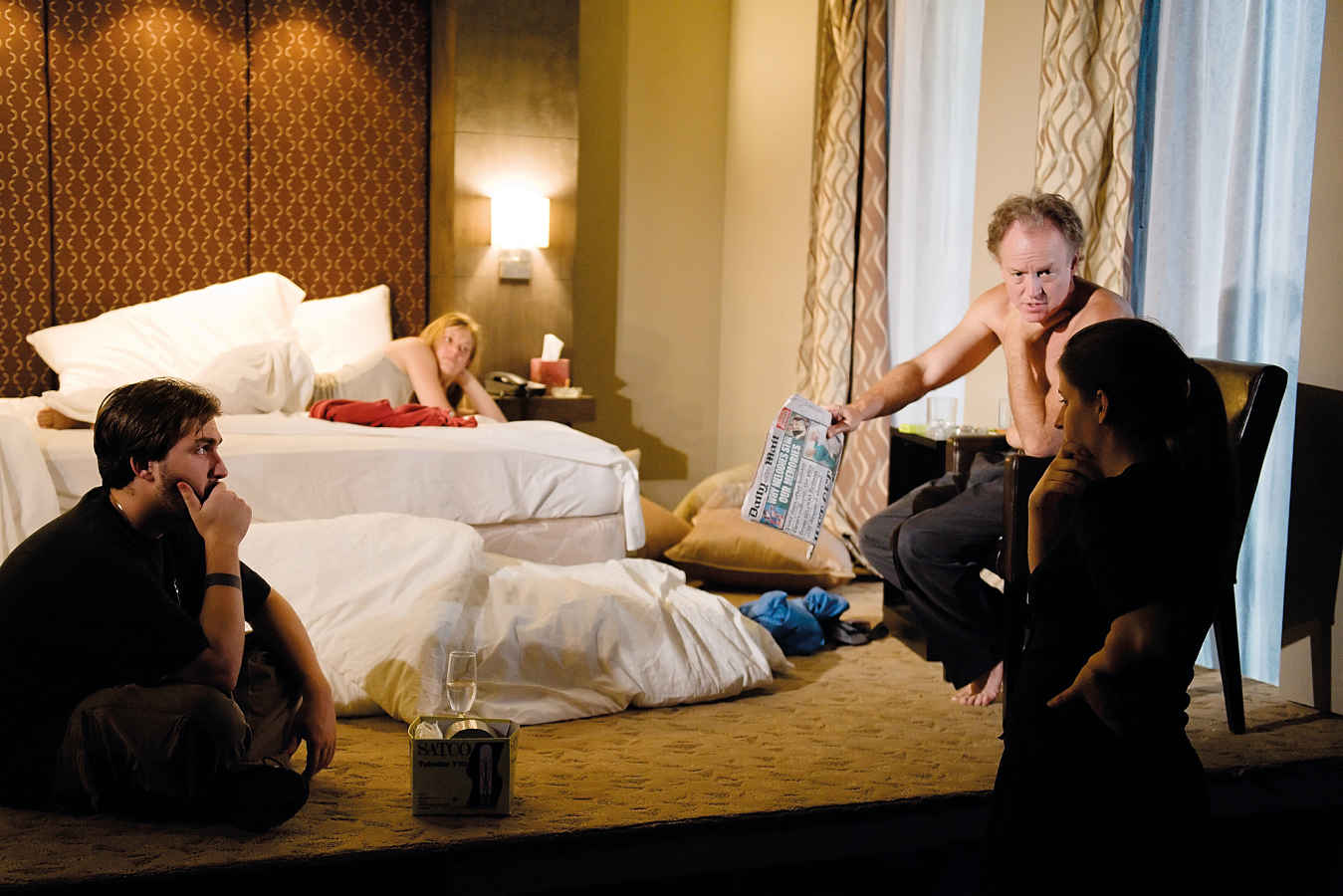

Blasted at Soho Rep was one of the most visceral experiences I’ve ever had in the theatre. Vanya exposed an intimacy and level of quiet and casual detail that made it feel as though audience members were experiencing upheaval in their own family, not one in late 19th-century Russia. And An Octoroon assayed its subject matter with such humor, intelligence, and theatrical inventiveness that if all high schoolers were given the chance to watch it, I guarantee you it would give birth to an entire new generation of playwrights in a decade’s time. Futurity was sheer and poignant joy.

And what did these productions have in common?

You just felt smarter, more enlightened, truly and simply better after a couple of hours, even while you’d been thoroughly and viscerally engaged. And these aren’t bad words—“enlightened,” “smarter,” “better”—though in the current climate they’re often stigmatized as such. Put aside the aforementioned impatience with anything that challenges; a cynical zeal to connect with anger related very little to what’s actually being discussed renders wealth—whether monetary, educational, or cultural—as something to be savagely and persistently reviled. And with it all the underpinnings of what has value in our culture.

Consider politics. In all likelihood one of our major parties will nominate a name-calling vulgarian who has helped push policy debate into a kind of theatre that used to be the stuff of afternoon shout shows. “Telling it like it is” as a sole virtue, if logically developed as an idea, means that to push language in rhetorically interesting ways is to insult or dissemble. The result is a kind of collective willful ignorance in which not to know, to be disinterested in elaboration and insight, is not only excused, but preferred. It’s a culture in which a 140-character offering constitutes the viable and preferred record of a person’s experiences, broadcast to a world ravenous for easy and disposable amusement.

The impact is exponential, because the noise that erases nuance, subtlety, texture, and challenge supplies its own inexhaustible justification for more of it. How else to be heard, watched, bought, or sold if not by being louder, more brash, more offensive, more violent. More…

And with this steady intake we become less patient, less sensitive, less imaginative, more easily distractible, maladroit in every way. We walk down the street and we see less. We confront tragedies and we feel less. We’re asked to help others and we’re less patient, less steadfast in our devotion.

Art, and specifically theatre, forces us to stop, to devote a few hours with others in the dark, many of them strangers, and to contemplate patiently—sometimes raucously, and often rigorously—versions of ourselves and our lives. These are often stylized and refracted almost beyond recognition, or distilled to such essential verities that you simply can’t stand a moment more. Or perhaps you never want it to end. But the aim, since its earliest iterations, has always been the same: not only to help explain and elaborate on our world, but more importantly, to sharpen our abilities to experience it fully.

With occasional exceptions uptown in the bigger houses, the places where this sort of work happens are small, and the runs often limited, yet the impact can be enormous. The plays I’ve mentioned tonight, along with many others we’ve produced over the years—including Mac Wellman’s Dracula (in which I got to appear as my own introduction to Soho Rep), or the work of Len Jenkin, Melissa Gibson, or David Lindsay-Abaire, to name just a few—inspire not only audiences but the people who work within these works.

Actors like Kevin Spacey, Marin Ireland, Reed Birney, Michael Shannon, performance artists like the Blue Man Group are but a smattering. Audiences and artists—and quite frequently we are both—who gravitate to and support small theatres like Soho Rep carry the experience out far into the world, which is wildly paradoxical because of our resolute intimacy.

And it’s that oxymoron with which I’d like to leave you tonight. That our little theatre, doing groundbreaking work in perspicuous continuity, with a tradition that goes back millennia, can—amid the noise, the clutter, the rage, and the impatience—make more of a difference now than ever.