Last weekend New York Live Arts presented a program of solo works by four women. This wouldn’t be news in itself, except that these were four writer/performers from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, most making their American debuts: Marie Al Fajr, Leyya Mona Tawil, Mona Gamil, and Amira Chebli. The program, which ran March 25-26, was part of NYLA’s Live Ideas Festival, which kicked off in February and has the full title of “MENA/Future: Cultural Transformation in the Middle East North Africa Region.”

According to Cairo-based artist and curator Adham Hafez, who partnered with NYLA director of programming Thomas Kriegsmann to program the festival, each solo piece raises issues that may not be expected of Arab female performers. There are no rallying cries against disempowerment, for instance, and no survival tales designed to engender empathy. This sets the evening apart, he said, from much of what is imported to U.S. venues from the region, which he characterized as “melodramatic work” that “just satisfies Orientalist expectations. I don’t find melodramatic work productive anymore. If ever.”

Marie Al Fajr, a French choreographer who has been documenting dying dance traditions in Egypt for more than 20 years, performed first with Shagarat Mussafira (Traveling Trees). She began slumped on the floor, face obscured, and took her time there in a kind of meditative state before commencing a range of movement sequences blending traditional Egyptian and contemporary dance. Her serene, assured presentation was set to a recorded score featuring the tabla, oud, rabab, and flute by Egyptian-Armenian composer Georges Kazazian. The net effect was enchanting and mellowing, a bit like taking a bath.

Syrian-Palestinian-American choreographer Leyya Mona Tawil’s Atlas, a collaboration with violinist Mike Khoury, followed. In the first half, Tawil, dressed in a knee-length army green coat and combat boots, rolled back and forth from stage left to stage right for what felt like an hour but was probably more like 15 minutes, thrashing, hurling at various speeds, as Khoury played a tense and urgent intermittent score. It was disturbing, uncompromising, and awe-inspiring. Tawil had earlier told me that the piece was about caving in to and pushing against the burden of knowledge. Viewing it called to my mind such turbulent visceral intensities as vomiting and rape. But it also evoked endurance. After the rolling sequence, Tawil lifted herself up and into the pose of Atlas holding the heavens—a balance made more majestic given that she’d been unfurling there, disorientated and discombobulated, so recently and for so long.

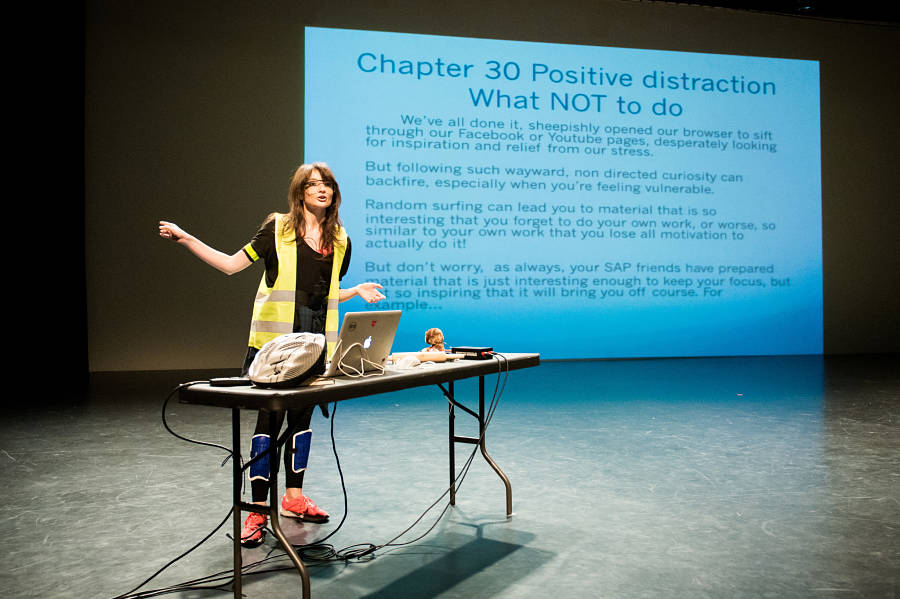

The next piece, SAP: Safe Art Practice, provided comic relief. Donning a bicycle helmet and shin guards, Irish-Egyptian performer Mona Gamil delivered a PowerPoint presentation selling a how-to book on “safe” art making. Gamil, a clever and beautiful polymath gifted in visual arts, dance, video, and comedy, has clearly strained under the pressure to define and market herself in more narrow terms for curators and grantors. There was evident glee in her satire of the commodification of art and artists, and the New York Live Arts audience, an international and intergenerational mix, joined in, laughing often.

In a prior interview, Gamil said that calls for Middle Eastern art in the U.S. tend to prioritize work that proposes solutions to sociopolitical issues.

“If the goal is to educate and emancipate, the kind of works selected will be very different from those selected based purely on aesthetic,” Gamil said. And while she wasn’t making a case that one is inherently superior to the other, she was concerned that “many artists are being marginalized and pigeonholed into the former. This limits what could have been a potentially rich artistic exchange into a monotonous debate that circles around a few key hot topics while everything else falls by the wayside.” Art, she said, should be a space that gives people the room to ask new questions, “rather than going back to the same ones over and over again.”

The final piece, In-Situ, belonged to Tunisian choreographer Amira Chebli, a dazzling young stage presence. Mixing boxing with virtuosic bellydancing, it was perhaps the most polished of the four pieces, with supertitles, sleek lighting, and a kind of self-awareness of star power. In an interview, Chebli called it a “dance play,” and said she was exploring how memories transfer to stage. “I take them out of their context and rewrite them the way I felt them, like a dream, a nightmare, or a fantasy, with the sounds and the lights that correspond to what they represent in my memory data.” She is also investigating what it means to be an Arab woman performing internationally—as she put it, “How does it feel to be in it, and what I see when I observe from abroad.”

None of the solos, nor any of the work appearing in the Live Ideas festival, was made specifically for American audiences. And since artists from the MENA region are underrepresented in U.S. venues, many of us who watch these pieces are doing so without much reference—a problematic Catch-22 that can keep new audiences at a distance. I asked Hafez an admittedly overwrought question about whether it was a barrier to fully appreciating the work if one was not sufficiently in command of the many current and historical political, social, and aesthetic contexts surrounding the works. He answered in one word: “Absolutely.”

Still, he said, “There is an expectation that art produced in the West is universal and that art produced [in the MENA region] is not. This is a flaw in how art history is constructed.” He suggested that festival performers are “bringing their own boxes”—their own categorical structures, not ones established in the West. “Let’s be aware that there is cultural hegemony. Look at the work with a fresh eye. There are set frames of contemporary curatorial practices, and it will take years to deconstruct them.”

I wondered, though: Is creating a program grouped by the artists’ gender one way in for American audience members who may be new to work from the region? It’s hard to say. Audiences hoping to come away from the evening with a unified feminist point of view or agenda would not have found it.

“They’re not there to talk about gender, but obviously it stems from a feminine and feminist perspective,” said Hafez. And, as there is a prevalent American media depiction of Middle Eastern women as disempowered, audience members who entered the venue drunk on that spiked Kool-Aid were likely to leave sobered up by the diversity and evident power of the performers. Said choreographer and NYLA artistic director Bill T. Jones, who conceived the festival with Kriegsmann, “We think [women from the MENA region] are oppressed or deluded. Then we see these women expressing themselves as individuals. That’s important for us to see.”

Another way to ask the question: Does a grouping by gender help or hinder the artists and their work? Among the quartet I spoke to, Tawil was the most critical of the idea. When we met a couple of weeks before the show for an interview at the NYLA offices, she admitted feeling conflicted that her piece would be marketed as a female solo, as she sees it as a collaboration with her (male) violinist. She wondered aloud abut the purpose of isolating women onstage in solos, rather than presenting each choreographer’s group work.

Ultimately Tawil was wary that any grouping—by gender and by solo work— might be a kind of “sub-marginalization” that changes who will choose to see the work and how it will be seen. “Instead of [the work] appearing in the wide open world of art, you’re going to be reading through the lens of MENA, and then reading through the lens of women, and then reading through the lens of solo. It puts a ceiling on the legibility.”

These are concerns she’s discussed at length with Hafez, whom she considers a great champion of her career. Theirs is a relationship—and this is a festival—that welcomes these tensions and conversations. Tawil noted that Hafez has presented her work in the Middle East in settings that have put their own physical safety and careers at risk. So however heated discussions and considerations get around this New York presentation, they seem tame in comparison.

“I can get behind [an all-female program] and I can critique it, equally,” she concluded. “There is an experimental voice, a future-thinking, future-building voice, coming out from the program. If you look at it in an ensemble way, the accumulation will have a big impact to represent the plurality.”