The sounds inside the Music Box Theatre on a recent March afternoon were hard-edged and piercing: tap shoes clicking out a tattoo on a stage decked out like a 1920s-style Harlem supper club, and then, once the actors cleared out for a dinner break, a drill wielded by a crew member, applied to the same stage. It was tech week for Shuffle Along, the old/new musical from writer/director George C. Wolfe and choreographer Savion Glover that will open on April 28, and both the show and the set were busy hammering their final pieces into place.

That may be why Wolfe himself also seemed a bit hard-edged, even prickly, that evening. Tech week is the time when every last decision counts, that precious private preserve before audiences make their entrance. And the stakes are high. It’s not just a matter of professional pressure: The lavish production, which stars Audra McDonald, Brian Stokes Mitchell, and Billy Porter, is Wolfe’s first Broadway musical since Caroline, or Change in 2004, and only the second* in which he’s served as a writer as well as a director since his last collaboration with Glover, the brilliant 1996 dance-ical Bring in ’Da Noise, Bring in ’Da Funk.

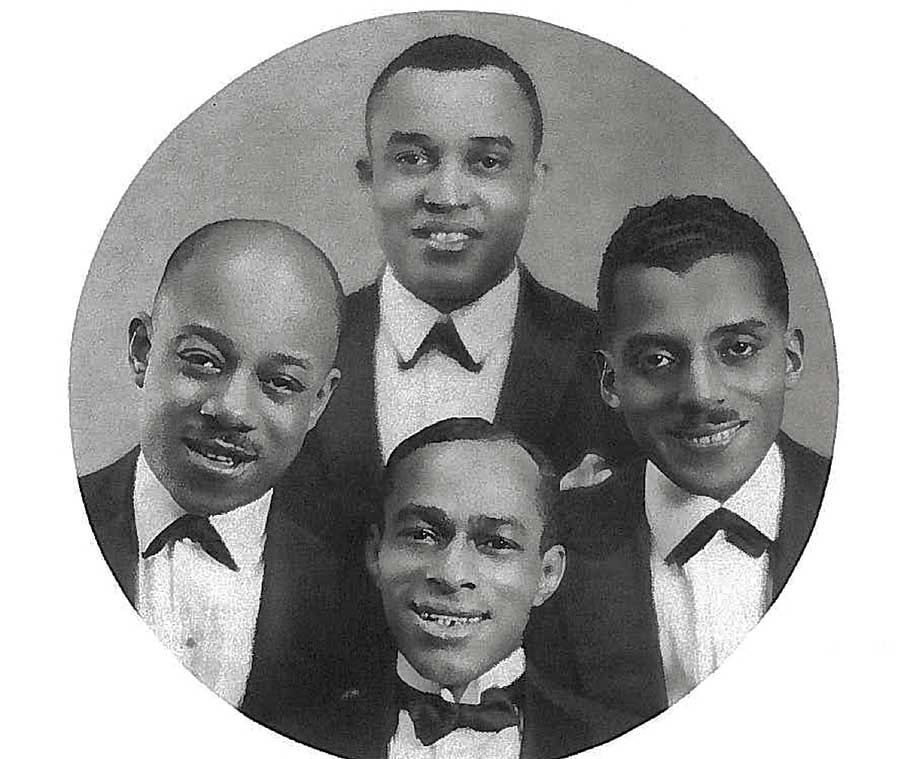

For Wolfe it’s also a question of wanting to do justice to the material: Shuffle Along is a nearly forgotten, never-revived-anymore 1921 hit that was Broadway’s first all-jazz musical, and as such one that did more than simply change the sound of musical theatre—it essentially gave us the classic showtune as we know it. Authored by two black vaudevillians, Flournoy Miller and Aubrey Lyles, and two black musicians, Eubie Blake and Noble Sissle, Shuffle Along also effectively popularized the Harlem Renaissance and ran for 484 performances before it toured, making stars of many of its performers and creators along the way.

So why isn’t it more widely known? (Good luck trying to find a cast album.) Wolfe has a few ideas why, which is part of what his show is about—though, as the subtitle he’s given it, “Or the Making of the Musical Sensation of 1921 and All That Followed,” indicates, the show promises in large part to be an original backstage drama that repurposes the score of the original Shuffle Along to tell the story of its creation and of the remarkable real-life figures who made it.

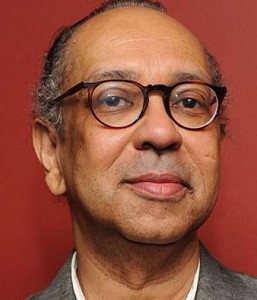

As he scarfed down takeout pasta in a stairwell at the Music Box, the polymathic director—a Kentucky native who, in addition to directing 18 shows on Broadway, ran New York’s Public Theater for a pivotal decade (1993-2004) and served as chief creative officer for the Civil Rights Museum in Atlanta—explained how and why he set out to reclaim this piece of Broadway history.

ROB WEINERT-KENDT: Your first major work was The Colored Museum, and you’ve since created an exhibit at an actual museum. Does Shuffle Along fit into a lifelong project of reclaiming or reframing history?

GEORGE C. WOLFE: No. Not in the least. The only thing the shows have in common is that The Colored Museum was about black people. Beyond that it doesn’t have anything to do with it—they’re completely different.

Okay. So this isn’t strictly a revival of Shuffle Along; you’ve written a new book. What’s the original book like, and how does yours relate to it?

It’s challenging. The book for Shuffle Along is like a lot of 1920s musicals. There’s the equation of operetta in it; there’s the equation of vaudeville; hints of burlesque. They’re beginning to tell structured and complicated stories, and then they’ll just stop for a musical interlude. I found the structure really fascinating because it’s sort of chaotic, but in a theatrically exhilarating way. It’s chaotic because a new form is finding itself. It doesn’t have the cohesiveness of what Show Boat figured out, but Show Boat couldn’t have figured it out were it not for Shuffle Along. It’s a form that’s based on a whole series of other forms, and something is starting to emerge that’s really interesting.

The song “Shuffle Along” appeared in Shuffle Along back in 1921 at the top of Act Two, so I figured out a way to configure it so it appears at the top of Act Two in my show, though it’s not being sung by the person who sang it then. So there are all these seemingly haphazard structural elements that Shuffle Along in 1921 had, and it’s been fun trying to preserve them and have that haphazard nature—to invest in those incongruities so they have an emotional texture to them and a storytelling dynamic as well as a thematic thing. So this is Shuffle Along; it’s inspired by Shuffle Along; it’s dissecting Shuffle Along; it’s an homage to Shuffle Along. I don’t think it’s just one way or the other.

It’s not like you’re trying to fix it and turn it into a well-made musical.

Exactly. That which is discombobulating about it I find exhilarating. The characters are really interesting thematically, but the people who are playing the characters are even more interesting. That’s always the case. I mean, save for certain roles—Mother Courage and Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? or Hamlet—chances are the actor is 50 times more interesting than the role. And the places that they went to in order to deliver these people—that’s also very interesting. I was intrigued by how Aubrey Lyles, who went to Fisk University and was studying medicine, ended up being an incredibly successful blackface vaudevillian on the Keith-Albee circuit. That’s fascinating to me. How did Eubie Blake, whose parents were both slaves, end up having a deep, deep desire to write musicals? He could write rags. He could write pop tunes. What he really wanted to write were Broadway shows. It’s astonishing to me that the child of slaves said, “I want to write a Broadway musical.” That’s an extraordinary thing. Why would he want to do that? Why would anybody want to write a musical? That ambition was startling to me.

And each one of the characters—there’s no reason that they should have formed a collaborative dynamic and decided to create a musical on Broadway. There is nothing logical or…

Inevitable.

Or inevitable about that. It’s like going A, B, C—X. It’s astonishing. If you view it as inevitable you’re lessening what was heroic about it, and also you’re missing the point of how this thing, which was jumbled, should have been jumbled, given the disparate personalities of the people who created it. You take Aubrey Lyles and Flournoy Miller and Noble Sissle and Eubie Blake, and James Reese Europe, who organized all the black musicians in the ’20s in New York City, so that when society people hired them, they all had to pay a certain thing; he was a surrogate father to Noble Sissle. You take Florence Mills, who was the greatest American star from 1922 till she died in 1927, and Josephine Baker, who became this exotic creature, and all these disparate energies. And Lottie Gee, who Audra is playing—who is this woman, who by the time she was 21 had toured three continents? Paul Robeson was obsessed with Shuffle Along, and was hired to be in it. How did this many brilliant people pass through there? When all those people were for some reason able to find creative expression and success inside of this seeming trifle of a show, that tension is extraordinary.

So why don’t we know more about it?

It got trashed by history.

Do you mean neglected?

No, it was actively trashed, actively dismissed, and reduced to something—some people called it a revue. It had revue-like elements, but it also had a book; there’s the story of Sam and Steve running for mayor. But it got dismissed and disregarded. That felt personally wrong to me, and I got very fascinated as to why that happened.

So it’s not just one of those old ’20s shows like Lady, Be Good, which has a ton of great songs but isn’t revived because the book is flimsy?

Well, before Shuffle Along there was no syncopation. There was no jazz score. There was no woman’s hoofing chorus. It integrated theatres in New York, and then when the show toured to all these cities, it integrated them. Sixty-Third Street went from a two-way street to a one-way street because of Shuffle Along, just because of the traffic. White people from downtown started going to Harlem because of Shuffle Along. So it’s not Lady, Be Good. You know what I’m saying?

It’s not just another one of these ’20s shows.

Precisely, with a great score and nothing else. It was in its day a cultural phenomenon. And how does something go from a cultural phenomenon to “Yeah, it happened”?

Isn’t one of the reasons it was subsequently dismissed is because of some of the racial tropes in it? It used blackface, for instance.

For two characters; everybody else was not. See, I get really angry about that. Someone said to me, “Oh, but there’s a song in there called ‘If You Haven’t Been Vamped by a Brown-Skinned Gal,’ and that’s racially offensive.” That statement is intrinsically stupid, because in 1921 the predominant entertainment aesthetic is light-skinned black women, and a song is coming along saying, “If you haven’t been vamped by a brown-skinned gal,” so it’s doing the exact opposite. It’s celebrating the full complexion and texture and colors that a whole culture has, a whole race has.

I mean, there’s this incredible cultural naïvete, incredible innocence to the piece. Flournoy Miller was sort of like, for lack of a better word, a low-level anthropologist. He’s not quite—he doesn’t have Zora Neale Hurston’s eloquence of language, but when he would tour around from city to city, he would hang out at barbershops and black places, and he would put some of that language in the show. There are some things colloquially that if we look at it with a level of judgment from now, we view it a certain way. Again he didn’t have the artful ear of a Zora Neale Hurston, but he was attempting to embody, honor, and embody Southern colloquial language. It’s very challenging and complicated to judge what is based on what was.

So I don’t think that’s why this show was dismissed. One of the reasons I think this show was dismissed is because it was so influential. Certain things come along and they’re influential and they live unto themselves. Some things come along and they’re trailblazers, and then people extract the juice of that which was unique about it and then move on. That’s what happened with Shuffle Along. I think that which was startling and unique got absorbed by the commercial landscape, and then in turn was discarded. Florence Ziegfeld hired Will Vodery, who did the vocal arrangements and some of the orchestrations for Shuffle Along, to come and work for him at the Follies, and then in turn he did the vocal orchestrations for Show Boat. He then hired the chorus girls from Shuffle Along to teach his Follies girls how to dance. I think the juice of Shuffle Along got extracted and inserted into the popular culture and whatever remained, remained, and whatever didn’t, didn’t.

Do you see that in racial terms, though—as another case study in the story of how black culture, black music, has been appropriated by mainstream white culture, then tossed aside?

I think that’s part of it; unquestionably it’s part of the equation. It’s also what happens when Fanny Brice performs at the Ziegfeld Follies; what portion of her ethnicity can survive, and what part does she have to tone down to be accepted by the larger culture? It’s the ongoing conversation of America: How do you hold onto who you are once America discovers you? How much of you gets to survive and how much of you gets diluted? That’s the same thing I think happening with Shuffle Along.

We think a lot about theatres of color and their future at American Theatre, and I know you started out at Inner-City Arts in L.A. I wonder if you see Shuffle Along partly as a case of a heritage not being handed down, a success not being built upon. Audra has spoken about how this piece of black Broadway history feels like an inheritance she didn’t even know she could claim till now.

If you don’t know the stories, then you can’t claim them. I wouldn’t call it a tragedy, but one of the consequences of Shuffle Along is that it was the first—the first monumentally successful black musical in the commercial landscape. So what book or article or owner’s manual could they read on how to protect it and honor it and make sure it was preserved? They invented something new, and it took off. They weren’t expecting it to take off the way it took off. So they’re enjoying not being poor, enjoying having touring companies, enjoying being invited to write scores, and Paul Whiteman and everybody is recording their songs. So they’re in the middle of this euphoria. They don’t know that they need to be keeping an archive of this work.

They weren’t thinking about building institutions or running a theatre, as you did.

Precisely. Always with success, you think successes Numbers 1 through 27 are going to follow. And they don’t always. Sometimes it’s just one. Sometimes it’s one and a half. All of that to me just makes it really, really fascinating. Because they went, “Ta-da!” and the world said, “No.” They had no opportunities, so they made an opportunity. I find that astonishing, that they just went, “Well, I guess we gotta. We can either run away or we can just do it.” And they did it, and then they struggled ridiculously hard, then it turned into a success, and then in the next year, 1922, there were five hit musicals like it; white producers prior to that time didn’t think a black show could be successful. Between then and the early ’30s, there was a plethora of those shows. Then they abruptly stopped, because, as Langston Hughes said, to paraphrase him, white people discovered Noël Coward and moved back downtown, and then the talkies came along. Also by that time, you have Gershwin, you have Irving Berlin, you have these incredibly successful and brilliant white composers writing, for lack of a better word, colored music. So what happened? The more you dig into it, it becomes richer and richer, because it becomes a story of the passion and the ferocity and the skill set and the cluelessness that is required to tell a story.

The cluelessness?

Because you just do it. My first Broadway show, I put in seven new numbers. People said, “That’s amazing!” I went, “It just had to be done.”

This was Jelly’s Last Jam?

Yeah. I wasn’t being brave. I was just doing it because it had to be done. The degree of sophistication I had was spent on making the number; there was no sophistication about Broadway or the institution or how I protect myself. You just do what you do. And they did what they did and it was astonishingly successful, and then time and life and history took over. And I just find all of that really incredibly very moving.

You know, I still have people come up to me and say, “I saw Noise/Funk 10 times. It was the most extraordinary thing I’ve ever seen.” And then you walk up to other people and they say, “What’s that show?” It’s gone. Theatre is fragile that way. Theatre is incredibly fragile. Unless the right people write about it, it becomes somebody’s distant memory.

Since you mention Noise/Funk, I want to ask about the way that show treated vintage tap dancing—in particular, the Bill Robinson character didn’t fare too well.

The character was named Uncle Huck-a-Buck. It was not Bill “Bojangles” Robinson. People have written about it as if it were. Your question seems to imply that you’re about to get on that same train as well.

I’m only asking because I feel like it goes back to—I don’t want to hit this point too hard, but about the way in which entertainment from that period can look wrong to contemporary eyes. And I’m asking whether something similar is involved here, and if that’s part of the context you’re trying to bring in—to show us what performance styles were like at the time, to put them in the context of their time, as opposed to criticizing them, as Noise/Funk did Uncle Huck-a-Buck.

Well, let me just tell you briefly where Uncle Huck-a-Buck came from. Savion spoke very specifically about tap dancers versus people who were hitting—who could hit. That was the whole phenomenon. You seem like you’re asking something about stereotypes, so what are you asking?

I’m talking about the image of a line of tap-dancing black folks in period costume, on Broadway, for a largely white audience—I feel like we’ve been schooled that there’s something not right about it, or that we need to put quotation marks around it, you know?

No, I don’t know. Say it one more time. I’m trying to figure out what you’re saying in terms of Shuffle Along.

Even the title Shuffle Along has a connotation to some people as referring to expected modes of black presentation or black performance.

I know what you’re saying, but I don’t understand where there’s a question in it.

I guess I’m not putting it in question form. Does your show confront these things, or approach them from a different angle?

I still don’t understand the question. I understand what you’re saying. I’m trying to understand what you’re trying to ask me in relation to Shuffle Along.

Well, having not seen it, I can’t ask it as specifically as I’d like. I guess, if you understand what I’m saying, if you could just comment on it.

There’s a line from Sunday in the Park With George, “Stop worrying if your vision is new; let others make that decision, they usually do.” So I really don’t waste a lot of time thinking about other people’s perception of what the work is. You do the work, and you try to extract—it’s acting. You don’t act a negative. You act a choice. So the thought process isn’t, “Shuffle Along is perceived as a stereotype, so how do I make it not a stereotype?” Then you’re not making a choice. Then the work isn’t fun or smart or inventive. You’re trying to not make a choice. As opposed to, if you have a choice and you mine it with truth and rigor and veracity of commitment, the crap that has been put on top of it gets exploded.

So you don’t make a decision to not do something. You make a decision to tell a story, and you tell that story as ferociously as you possibly can. What happens after that, happens after that. And all the crap that someone who wrote a bad book, or someone who wrote a blog explaining away a piece of culture, gets blown up in the process. But you don’t think about those people when you’re doing the work. That’s why when I have three people say to me, “Oh, ‘Brown-Skinned Gal’ is an offensive song,” and I put six stunning women onstage while people are singing those flawless harmonies—end of conversation. You don’t waste time discussing what it isn’t. You explore what it is, and in the making of it, hopefully you illuminate something inside the material that has a degree of truth or honesty or rawness or wit or fuck-you that makes the moment vibrant.

The Wild Party was done in Austin, and all these black students staged a die-in. And I was going, “Really? I’m sure you were passionate about it, but you spend your time attacking a musical? Really?” You know what I mean? I understand why without a context they could have been to think that was important, and I respect that. But it’s like, “Oh, I’m not going to do Othello—Othello gets duped by a white man and he gives up all his power for a handkerchief.” Okay, that’s one way of looking at it.

It’s a pretty narrow reading.

That’s what I’m saying. It’s true: A black man gets duped by a white man, and he’s in love with a white woman, and he surrenders all of his power over a handkerchief. That’s a very specific way that you can dismiss Othello. Or if you go inside it, maybe you can unearth something that’s 80 times more complicated than that. So you can dismiss Shuffle Along based on what the title says, and all that other crap, or you can go inside and figure out why all these brilliant people attached themselves to this project. Why did the smartest black people uptown, and why did the smartest people downtown find themselves exhilarated by this material? Now you can, from your narrow perspective, say, “Oh, well, because it was serving up to white people what white people wanted to see.” The people were just trying to make the rent. They were just trying to make the show. They didn’t have time to engage in some sophisticated, crappy, “Well, this is what white people like, so I’m going to do it.” Any of those things that we impose upon the material have nothing to do with the intrinsic nature of the material. Shakespeare wasn’t writing a play in which he was celebrating the stupidity of a black man functioning inside a white culture. He was working with something else. So that’s what I have to say to that.

I’m glad you gave that answer.

Does it make you understand what I’m saying? Really, I get very angry about these questions. Because any time anything black is done, it has to serve every single purpose. This much black stuff gets done [indicates small amount], and this much white stuff gets done [large amount].

There’s more scrutiny.

It has to serve more needs. Billy Porter, who’s in the show, said that when he was at Carnegie Mellon, he and his friends used to joke and mock the show. “Oh, let me go shuffle along.” You know. Clueless people with intellectual arrogance love dismissing anything that doesn’t look like them.

I feel like a lot of your work has been at the intersection of entertainment and discomfort.

Precisely. While I love applause, I don’t give a shit. I don’t. I’m just in awe, completely and totally in awe that two teams of vaudevillians got together in 1920 and substantively changed the American musical.

And we don’t know about it.

We don’t know about them, and we need to know about them. We know about West Side Story. We know about Oklahoma!. We know about Show Boat. We need to know about Shuffle Along. End of all other conversations. When you are willing to put West Side Story, with its view of Puerto Ricans, and Show Boat, with its clearly questionable view of all the characters in there, to the same level of scrutiny, you can have this conversation about Shuffle Along. You understand what I’m saying?

*This story originally stated that Bring in ‘Da Noise was Wolfe’s last Broadway effort as both writer and director; in fact, he cowrote the book of 2000’s The Wild Party with Michael John LaChiusa.