Welcome to the house of Basil.

Watch your step—you might run into a clothing rack, or a ship carrying a crew of human-sized puppets, or ghost marionettes hanging from the rafters. Or a camel.

It is September 2015 and renowned puppeteer and director extraordinaire Basil Twist has turned the Abrons Arts Center, a presenting house in Lower Manhattan, into a puppet-maker’s paradise, with rehearsal studios, build shops, and a costume shop all working around the clock to bring Twist’s newest show, Sisters’ Follies: Between Two Worlds, to life.

“I know it’s still pretty loosey-goosey, but it’s gonna be shaped like that,” Twist says, as the rehearsal breaks for dinner at 6 p.m. It’s 16 days until the first public preview on Oct. 1 (the press opening is Oct. 7). Today was the first run-through with all of the big backdrops, set pieces, and larger—albeit half-finished—puppets.

When I first poke my head in, the company is in the middle of the show’s final scene, “The Dybbuk,” based on the Yiddish play by S. Ansky that ran here in 1925. The scene is set in a graveyard full of cardboard tombstones and flying ghost puppets made of silk, where a Jewish wedding is underway. Twist is calling out cues via a microphone.

“We’re a little behind the build,” confesses build master/puppeteer Jessica Scott. “My main push is to get everything up to basic functionality, and the last week will be dressing everything the fuck up.” Scott lists what’s left to do: Dress the camel and finish its head, replace some joints and handles on some puppets, make heads for the ghost puppets, and build some birds. The ghosts, she notes wryly, “may not have heads in previews, but we’ll see where we get.”

Twist isn’t worried; Sisters’ Follies is about 50 percent complete, and that’s “par for the course for a Basil Twist show,” he says with surprising calm. It helps that his team has been building the show inside Abrons since late July, instead of at a studio off-site, then reassembling it onstage. It’s a rare treat for Twist, and it means he has plenty of room to indulge.

“So of course we’re just making this bigger and bigger and bigger,” he says over a plate of food. “I feel like I can push the capacities of the building to its max. And that’s part of what’s special about this building: to just have space for three months to prepare the show. I can pull the line sets myself. I can go up and down to the pit. I can play. It’s an inspiring building and situation.”

How did Twist, who has a studio but no resident performing home, happen upon this amazing real-estate coup? It began three years ago when Jay Wegman, artistic director of Abrons, approached Twist with the center’s first theatrical commission (they’d commissioned only dance pieces before). The occasion was the 100th birthday of the Abrons Playhouse, a 300-seat venue and the center’s largest theatrical space. The amount was $160,000—the largest Abrons commission ever.

“We wanted something with a broader appeal, and we wanted something incredibly original and unique to celebrate an incredible and unique building,” Wegman explains over the phone. Twist has done several workshops at Abrons, as well as the 2011 remount of his puppet/drag extravaganza Arias With a Twist. “Basil loves the space,” Wegman continues. This was a basic qualification for the job: “I wanted someone who loved the space and wanted to celebrate the space. He just was the obvious person.”

The Abrons Playhouse was founded in 1915 by sibling coal heiresses Alice and Irene Lewisohn. They named it the Neighborhood Playhouse, and for 12 years, produced and starred in a number of avant-garde theatre and dance pieces there, including an annual revue called “The Grand Street Follies.” Luminaries of that era who graced the playhouse stage included Martha Graham, Ernest Bloch, Kurt Schindler, Agnes de Mille, and Laura Elliott. Art aficionados may recognize Irene Lewisohn’s name, as she later founded the Costume Institute at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. In 1927, the Lower Manhattan site was renamed the Henry Street Playhouse, while the name Neighborhood Playhouse followed the Lewisohns to their next venture: founding the acting school on 54th Street that would one day be the home of Sanford Meisner and his famous technique.

But the theatre on Grand and Pitt streets kept presenting cutting-edge theatre and, in particular, music, including works by Aaron Copland, Philip Glass, John Zorn, and Lou Reed. More recently, theatre artists like Richard Maxwell, Pig Iron Theatre, and Taylor Mac have strutted their stuff there.

To explore the long history of the center, Twist originally planned to use the Lewisohn sisters as a framing device. But all that changed when he brought in two close friends and collaborators: drag performer Joey Arias and burlesque artist/dancer Julie Atlas Muz, who, like Twist, are downtown performance legends who have been onstage at the playhouse before.

“I just had a hunch that they’d be great together as the sisters and as ghosts—they’d be flying and it would be so cool,” Twist recalls. “At first I thought maybe they would be the emcees of some sort of revue of all the history. But as soon as I got Joey and Julie together and I felt how great they were together, I said, ‘Oh, this is all we need: the story of the sisters. It’s rich enough to just focus on that.’”

The show, which covers just the formative years of 1915 to 1927, opens with Arias and Muz as the ghosts of the Lewisohn sisters, flying on wires in long white dresses and singing Irving Berlin’s “Sisters.” What follows is a sort of revue inspired by the “Grand Street Follies,” with seven scenes that recreate (and spoof) seven different shows mounted at the playhouse in those 12 years. During scene changes, Arias and Muz appear in prerecorded projections, giving historical background and verbally sparring (as sisters do). There’s also a certain amount of physical sparring, with Arias and Muz on wires whacking each other with giant hammers and gamma ray guns. It’s historical, it’s cartoonish, and above all, it’s grand.

That ambition and irreverence is fitting for an experimental venue that holds special significance for many. “I have a very strong connection to this theatre,” says Muz—who plays the younger, goofier sister, Irene—from an aisle seat on a rehearsal break. Her husband is performer Mat Fraser, with whom she performed an acclaimed burlesque adaptation of Beauty and the Beast that ran at Abrons in 2014. “I live just down the street. I got married on that stage.”

A few others feel a slightly different connection to the theatre: They frankly think the place has ghosts. “I always feel there were ghosts here,” says Arias. “I thought they were two children, but maybe it’s the sisters. There was one upstairs one time years ago, about five years ago, and one downstairs. I didn’t see them; I just felt them. That was crazy.”

When creating a puppet spectacle, you’re always in tech. “You cannot move forward if the string is too long on a puppet,” explains Twist. “So you stop, you shorten the string, and then you move on. It’s like tech—even though it’s low-tech.”

Also, you’re usually working on multiple things simultaneously. While most plays have script and music largely completed before visual elements are added, for Sisters’ Follies, puppet construction, music, text, and staging have been moving on parallel tracks simultaneously since early July.

Twist usually builds a scene by quickly constructing props and puppets out of cardboard, then playing around with blocking. Then “we may stop in the middle of staging it and say, ‘We need to build three more of these cardboard things,’ and we take five minutes and we build them.” Then, after a bit more staging, he may think: “Oh, wouldn’t this be cool if it was on strings?” Lather, rinse, and repeat for three months.

It’s similar for the writing process, which would not be alien to those well-versed in the world of devised theatre. “[Julie and I] started ad-libbing, [Basil] would tape it, listen to it, and pick what he thought he liked,” explains Arias, who previously starred in and co-created Arias With a Twist. Arias plays the older, calmer sister, Alice Lewisohn. Twist, he says, would include “bits from Alice’s diaries, and ad-lib it with our words. We tweak it still as we go along.”

Twist describes the resulting show as “less of a pure puppet show [and] more of this bizarre play/musical that has a lot of puppets and stagecraft in it.”

After all, Twist is an auteur with a predilection for singular stage spectacles: Berlioz’s “Symphonie Fantastique” staged in a fishtank, the mechanical-box theatre of Dogugaeshi, assorted operas and ballets. In Sisters’ Follies, the seven scenes run the gamut in style and scope. “The Queen’s Enemies” is set in Egypt. During the climax, the stage floods with “water”—an expanse of silk stretched over half the stage, which is then pulled back to reveal dead Egyptian puppets (made to look like hieroglyphs) and flopping fish on wire. The more postmodern “Salut au Monde,” inspired by Walt Whitman, features dancing boy puppets, a Clavilux (a “light organ”), and Arias and Muz in full song-of-myself drag.

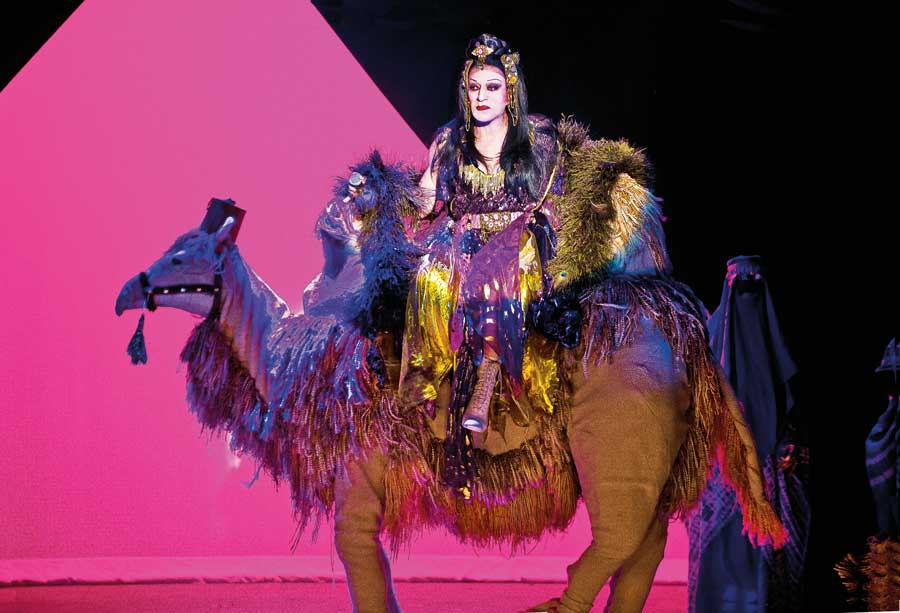

There are musical numbers, of course. “Arab Fantasia” takes place in an Egyptian marketplace, with Arias entering the stage atop a camel puppet (operated by two male puppeteers). The concept may have a whiff of cultural appropriation, but it’s rooted in the playhouse’s history. Says Twist: “[The sisters] took a sabbatical for a year and closed the playhouse. They were in Egypt and India and Burma, and the piece was inspired by that.”

In Twist’s vision, of course, the emphasis is on camp; at one point, Arias busts out a microphone and sings Maria Muldaur’s “Midnight at the Oasis,” while the camel does a shuffle, a rattlesnake wiggles along, and puppet monkeys fling poop at Muz. The song was Arias’s idea.

For Muz, on the other hand, breaking into song was the last thing on her mind. When Twist told her early on that she would be singing Jefferson Airplane’s “White Rabbit,” she says she replied, “What the fuck are you talking about? No one goes to a show to hear me sing. They go to a show to hear Joey sing—they go to a show to see me dance naked!”

Several weekly voice lessons and daily vocal warm-ups later, Muz is singing “Go ask Alice” while sitting on a boat amid a sea of blue silk (while a shark fin eerily swims past). But she does get a half-naked dance solo in a wordless, Druid-inspired scene called “Kairn of Koridwen.” She’s also the show’s choreographer; the show’s 12 puppeteers also doubled as backup dancers and singers (talk about triple threats).

“It’s very overwhelming,” concedes Muz. “You can’t be on the outside giving notes. And I start looking at too many things and then I’m like…what’s my part?”

As the three collaborators tinker with the script, Twist is talking to the show’s music director, Wayne Barker, about creating original arrangements for the songs. Indeed, Sisters’ Follies has turned into something like a full-blown Off-Broadway musical, with Twist’s own production company, Tandem Otter, coming up with an additional $42,000 to hire five live musicians, bringing the show’s total budget to $202,000.

In addition to arrangements of all the show’s cover tunes, Barker is composing incidental music for Sisters’ Follies. Two weeks before previews, half of the underscoring is finished, and while the cast rehearses in the evening, Barker sits in the lobby composing on a keyboard and laptop. He explains that Sisters’ Follies is not like a typical musical in which music is composed, then the performers figure out how to move to it. “A lot of this project is more like scoring a movie,” Barker says. “You let Basil and the puppeteers figure out their own rhythm.”

Says Machine Dazzle, the show’s costume designer, “I think this is turning out to be a much bigger show than they ever thought.” Dazzle is doing the job of an entire team, sewing 95 percent of the costumes and fashioning the wigs (during the show’s run he’ll also hand-wash Arias and Muz’s intricate dresses). He lets me try on one of Arias’ wigs, a long brunette number with flower and feather pieces the size of a person’s head. It’s pretty heavy. “It’s selfie time,” he says. (Sorry, not sharing that pic here.)

For Dazzle, the toughest costumes have been the 12-foot-long ghost dresses that Arias and Muz wear during their wire scenes. Such ambitious visions aren’t always practical when there’s so much to be done and you’re the one doing all the sewing—especially when two dresses turn into several more. It turns out, Dazzle says, that the full-length dresses don’t work in every scene, “so then they had me make medium ones. And Julie wanted to be acrobatic, and she’s doing all these twists and turns and flips during the ghost battle scenes, so she needs a shorter one, so I’ve made yet another one.”

He also has yet to distress the dresses to make them look old, as well as drip-dye and bejewel them. And it’s just two weeks till first preview. “Technically, I’m sort of halfway through, at least with working costumes,” Dazzle says. “Nothing has truly been fitted; none of these have even been tried on. They’re not going to have finished costumes until probably opening night.” He chuckles good-naturedly.

It’s the first dress rehearsal, three days before first preview, and it has just been announced that Twist is a 2015 MacArthur “genius” grantee. It comes with $625,000, dispersed with no strings attached over the span of five years. When I ask him what he plans to do with the money, he shrugs and says, “I don’t know. When I’ve won awards before, they go right back into my work. Bigger puppets.”

For now, Twist is pulled in multiple directions. A typical morning for him includes checking on the puppet build backstage, helping draw backdrops in the garden, and going over paint swatches. Come evening, he switches to director mode, whispering suggestions about the projections to the technicians, and giving notes to Arias and Muz. These range from, “Just keep the story between you two” to “You guys look fucking amazing.”

With just three days before an audience sees Sisters’ Follies, there’s a new ghost puppet in “The Dybbuk” that Twist dubs “the BBG” (big black ghost); it’s almost as tall as the stage. There are no sound cues, and Arias and Muz finish the last half of their show in working costumes. Meanwhile, Twist is fielding phone calls from reporters about the MacArthur prize.

Amid the frenzied atmosphere of activity, there’s still room for levity. “I haven’t played a man since 1989,” quips Arias as he takes off his Walt Whitman beard. “It feels weird.”

Reviews are mixed after the show opens on Oct. 7. Ben Brantley, who has gushed about Twist’s work before, writes in the New York Times that the lead performers “are surprisingly static,” and that in general the performers are “upstaged by the supporting puppets.” At the same time, Brantley gapes in awe at the visuals. His closer: “In the best of all possible worlds (or two worlds), New York City would give Mr. Twist an unlimited budget to do up the town for Halloween in haute-scary chic.”

Time Out New York’s Adam Feldman is more blunt, characterizing the show as “imaginative but muddled,” and singling out the script as filled with “bland, stodgy exposition and lame special-material lyrics.”

Twist, who sits in the audience for most of the run (one weekend, he steps onstage as a puppeteer), chalks up the critical brickbats to the downside of the short preview period for downtown shows, in which changes are still being made after the show opens. “There were a few video cues that were added [after opening],” he says. “Downtown, we don’t have the ethic of ‘the show is locked.’ We could keep adding little things, playing with it. That was part of the joy of that.”

The show is apparently review-proof, though, extending for an additional week; its closing date is Nov. 7. For her part, Muz wishes it could run longer.

“If [the show] could have been what it had been at the end of the run on opening night, I would have been thrilled,” she says. “This was at the level of a big, huge Broadway show. It was all of the set changes and the live music, and all of that was so ambitious. Because this was in the milieu of experimental theatre and we did it very quickly, we did not have time to gestate. I wish that we had had a month of previews, which is common in Broadway shows, and then a run.”

Still, Sisters’ Follies did what many commercial productions aspire to and few actually do: It recouped its expenses, as audiences grew steadily as the show progressed. To Wegman, the show was a success beyond what he could imagine when he commissioned it. “I’ve been here for 10 years,” says Wegman, who counts Sisters’ Follies “in the top three favorite things that’s been in there” during his time.

And both Wegman and Twist believe they got raves from the critics who really matter: the ghosts of Lewisohn sisters.

“Obviously, it was a huge, ambitious show, and it had this volatile and messy quality to it, as it should in a downtown show with a bunch of freaks,” says Twist. “How thrilling it was to think about this theatre and to celebrate it in a fresh way. The ghosts, the history, and kind of recreating those original pieces and informing people of the history they didn’t know about. We all who work downtown stand on the shoulder of these fierce ladies in more ways than one.”