For more information about the actors in this story, scroll to the end or just click on their names.

Carrie Coon sat in the corner of her apartment wearing a slip, heels, and pearls. She sipped her brandy and made her grocery list.

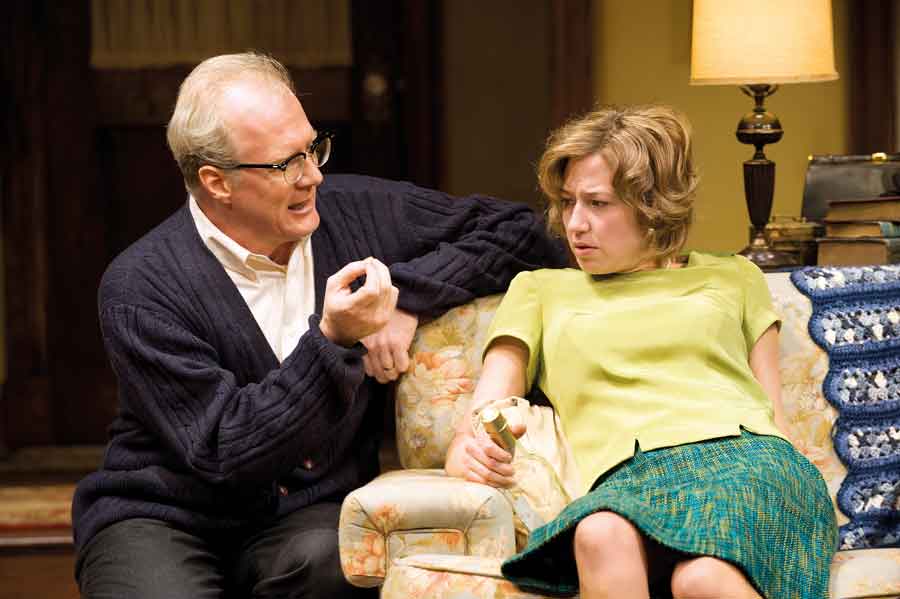

Coon wasn’t actually going shopping. And brandy wasn’t really her thing—she had never drunk it before developing this little ritual. Coon, who would earn a Tony nomination for her role as Honey in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, was still a long way from the Broadway stage and wasn’t even yet in the rehearsal room for the original Steppenwolf production that would make her a star. This was Coon preparing for the audition.

“I was learning to be idle,” Coon says, all the better to get into the mind of Honey, a woman of a certain era, living a life “with nowhere to go.”

Acting is about finding the spontaneity that makes a character and the play come to life front of the audience. But getting there takes years of practice—from classroom training to research and text study to rehearsal to physical and mental exercises before and during the actual performance.

“Everything is preparation so you can get to that point where you are living in the moment,” says Stacy Keach, whose meticulous preparation throughout his career helped him earn four Drama Desk, three Obie, and three Helen Hayes Awards, plus a Tony nomination. “Bad acting comes when you are indicating, when you are aware of what you are doing. All the preparation is needed because once you are onstage you don’t want to be acting; you want to be expressing yourself as the character.”

Preparation starts in school but the lessons last a lifetime. Keach points to an idea he was taught at the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art, that “in rehearsal you should research as many alternate ways as possible to express yourself. The more choices you have at your disposal the better your performance will be, because you can be spontaneous and the other actor will respond spontaneously.”

Stephen McKinley Henderson says his education began in high school, when his instructor Gloria Terrell taught him that he could not play Karl Lindner in A Raisin in the Sun as a villain—that he had to find a way into the character’s mindset.

“She taught me that no matter the size of the role, every character is the lead in his own life,” Henderson says, adding that these lessons were later reinforced when he studied Meisner with Bill Esper, who emphasized that “your character came from somewhere and is going back to somewhere—they are not just briefly appearing on the stage.”

Terrell also taught him to find “the living roots inside of you, that thing that is uniquely you—your life, your history—that you can bring to the role.”

At Juilliard, Henderson recalled, Marian Seldes stressed that “an artist can have style and not be false—that style is the incantation of the poetic,” a maxim that would prove invaluable when he prepared for the many roles he tackled in plays by August Wilson, “the poet-playwright of my own culture.”

Most schools try to prepare actors by giving them as many different tools as possible. Crystal Dickinson says the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign incorporated everything from Laban to Meisner to clowning. Now teaching at her undergraduate alma mater, Seton Hall, Dickinson gives her beginners a taste of Stanislavsky and Laban and others, “since some students work outside-in, and some inside-out.”

While New York University places students in a particular studio, Jon Norman Schneider says that ironically this taught him the same lesson gleaned by actors who study in programs that take a “bigger toolbox” approach.

“I learned to gauge my own sensibility to see what was useful and what was not, and to not adhere to one style rigidly,” says Schneider, who spent three years in the Lee Strasberg Studio at school. Schneider continued using exercises he learned at NYU to prepare for parts by developing a strong sense of his character’s environment, evoking a sense memory of smell or touch. But while he found it effective to employ affective memory—using an intense memory from his own life similar to the emotion of his character to get to that place—during his school years, he confesses that he hasn’t used it once in his professional career. “I find other ways into my character or the moment,” he says.

The course at Cornell that Maria Dizzia found most valuable was actually one on directing. Seeing theatre from the other side showed her “how little ‘good’ matters—good is in the eye of the beholder, and as a director you just want something to be happening. Before that I had been unwilling to try something if I was not sure it was good. But I learned the best thing I could offer was to give it a shot and just keep doing it.”

For Daniel Duque-Estrada, the lesson that still resonates every time he goes onstage came from a class with Thom Jones at Brown. Duque-Estrada performed a monologue “but I was off my base, leaning forward, shoulders around my ears.” Jones asked if he could touch him. When the professor touched those tensed-up shoulders, Duque-Estrada “recoiled as if he was touching a hot stove.” Jones showed Duque-Estrada how blocked he was, and how breathing would let him feel all the way down to his feet, and how giving his conscious mind something to do—focus on breathing—would allow his subconscious mind to do its best work.

Duque-Estrada remembers Brian McEleney, the head of Brown’s acting program, telling him that when he was pushing too hard physically, “You think you’re acting the shit out of the part, but you are literally pushing the audience away from you. Vulnerability is a matter of breathing.” Duque-Estrada says he relearns those lessons every day. “Now my way into a character is through my technique. I focus on the tactical, and my subconscious does the creative work.”

A locked-up physicality is something Coon also faced in her training. American actors tend to lead from their head, she notes, and disconnect from their body; as a college athlete, she “had the body awareness but not the emotional connection,” which she learned in graduate school at the University of Wisconsin. “It is startling how much trauma we hold, and releasing it is a messy thing—it’s not fun, but it is liberating.”

Oddly enough, much of what still remains relevant to her from her training came from one teacher, Susan Sweeney, who emphasized the International Phonetic Alphabet. “When I went home to Ohio for Christmas after that, I thought my whole family sounded like pirates,” Coon says, “I had no idea. And I realized that dialect really connects to identity.”

Sweeney also stressed the importance of preparing properly to play stylistic or period pieces. “Nobody stands up straight anymore, but you can’t play a princess if you don’t stand straight,” Coon says.

Coon’s meticulous preparation for her Steppenwolf audition for Honey grew from those lessons. Her research included pulling out her trusty Timetables of History, a reference book that gave her a sense of what music was popular and what books people were reading in the period of the play. In addition to the pearls, slip, and brandy rituals, Coon walked around “exclaiming things” with a Honey-like effort at enthusiasm. “I wanted to find her voice, which I knew would be higher than mine,” she says, adding that she also watched Uta Hagen training videos online and learned “that the pitfall when playing a drunk person is that you don’t want to play drunk—that person is trying not to look drunk, and so they are being very careful.”

Coon sees this rigorous preparation as akin to her training in soccer or track. “The idea is the same in sports and acting: that discipline and preparation works so that when the moment comes, you are free and available to be in the moment.”

Once the part is won, actors start preparing for rehearsal with a close read of the text. Dizzia says she prefers “to learn by doing—I’m better on my feet,” but she gained a knack for text analysis from her University of Caliornia—San Diego Shakespeare course. “That’s the way I read any script now,” she says. “I want to honor the comma a playwright put in, so I think, ‘Does it help me make sense of that line?’ Anne Washburn and Sarah Ruhl are poets—where Sarah has a line break is not arbitrary, and you can tell something about what the character is thinking if you can figure out what the punctuation is telling you. It’s the same with Adam Bock, who writes contemporary speech with people interrupting themselves and repeating themselves.”

This in-depth reading proves crucial once she is in rehearsal and onstage, as it gives her the self-confidence to let go. “It allows me to stand still and have thoughts as the character,” she says. “If I don’t do the work, I get antsy and think, ‘Should I just do something?’ But that is an impulse that is not related to what is happening in the play.”

Schneider confesses that he was “terrified” when he started reading Clifford Odets’s Awake and Sing! “Never in a million, billion years did I think as an Asian American that I’d be cast in an Odets play,” he says. “The language was so specific to this family. I was overwhelmed. But after my initial freak-out, I realized I had to go back to the text and work past my own insecurities and just remain open and curious.”

Lincoln Center Theater. (Photo by T. Charles Erickson)

Sometimes the text does not or cannot contain all the answers. Dickinson says she approaches acting more through the body than the mind, but knows you have to do the mind work first. “You have to learn the character and know their world, and then you can let it fly,” she says.

In the first act of Bruce Norris’s Clybourne Park, her character, Francine, doesn’t have much to say—which, she recalls, offended some people. But Dickinson, whose minor in college was African-American history and culture, wonders what would be appropriate for a maid in a white family’s house in the 1950s. “If you have an understanding of what the country was like at the time, you know that. My grandmother was a maid and knew what she could or could not say.”

So Dickinson decided she would invest Francine with “a life outside the door. I decided she liked picture shows,” says Dickinson, instinctively slipping into the period’s terminology. So she watched a steady stream of movies from the era, movies her character could have enjoyed with her husband. “Having an outside life gave me a dignity Francine needed to withstand that household and think, ‘This is not my life.’”

But an actor can prepare too much, Duque-Estrada cautions. He typically reads scripts before rehearsal, keeping a journal that will later “fill the well up.” But to play Elliot in Quiara Alegría Hudes’s The Happiest Song Plays Last at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival, he thinks he went overboard.

“I came in completely off book on the first day, which was a big mistake,” he says. He was nervous about joining the cast because it remained largely intact from an earlier OSF production of Hudes’s Water by the Spoonful, and because he had first visited the festival as a student. “Most actors want to get to Broadway, but Oregon Shakespeare Festival was that place for me,” he says. “I was jumping out of my skin about being there, and I knew the role was not a slam dunk for me and that I’d have to be diligent.”

Of course, memorization is often a crucial part of the pre-rehearsal process for Duque-Estrada, as it is for many actors, but he realizes now that it’s different for a small, secondary role. When you’re playing the lead, leaving room to grow may be important.

“At the first table read I thought, ‘Man, I got this,’ but quickly learned how wrong I was, and how I had wasted everybody’s time,” he says. “I thought I would stay open, but my brain had made choices.” Duque-Estrada says he’d placed Elliot’s voice “up here in the mask when he was excited,” and saw Elliot as someone who had hung back in the previous play, but “who very much engages here, to connect with people.”

He says he was playing Elliot “like a Roman candle, constantly bursting, pushing for effect.” Then director Shishir Kurup pointed out that the play is about Elliot finally connecting; though the character “does not go to the world, he has opened up if the world will come to him.”

Eventually it came down to breathing and staying in his body, but Duque-Estrada says he feels “silly” about the way over-preparation undermined his early work. “I had to work to reframe my mindset. I made my job more difficult.”

Schneider agrees that having a director who is both patient and assertive is helpful. In Awake and Sing!, he says he was “too timid at the start” in his handling of the Depression-era Bronx Jewish dialect. “I still felt inauthentic and the rest of the cast was more confident.” Director Stephen Brown-Fried “wasn’t afraid to steer me in a different direction or to say, ‘Knock that off,’ so I could get out of my own way and serve the story,” Schneider says, adding that the biggest lesson for him in readying himself for this play was not to have preconceived ideas about expectations and results.

Henderson emphasizes that there are not rules that apply to every play, every role. “I know principles, but I don’t get locked into rules,” he says, adding that at SUNY Buffalo, where he’s a professor in the department of theatre and dance, “I teach my students to take the principles with you but leave rules behind.”

For Henderson, finding his way came from the six questions that director Lloyd Richards taught him to ask as he prepared for each scene: What experience was his character coming from? What was he coming to? What was he coming to do? Why? Why now? What did he expect to happen?

“As I answer those questions, I get further away from being an actor asking objective questions, and then I can make subjective character decisions,” Henderson says. This is helpful both for what’s on the page—and what isn’t. “If the text does not have the answer now, I can create that, as long as I don’t betray the text. Lloyd said, ‘You fortify yourself with justified reality.’”

Henderson says he also often goes beyond Richards’s questions as he prepares, sometimes reflecting on what Harold Scott, who headed the MFA directing program at Rutgers University, taught about following the money: how it gets spent in the world of the play, who pays for things, and how those things get used. “There are so many options to help you go deeper and deeper,” Henderson says.

For the role of Abby in Amy Herzog’s thriller Belleville, Dizzia found some answers in her own dreams, aided by a coach named Kim Gillingham, with whom she had worked previously. Dizzia found it “easy to get into Abby’s body but difficult to stay there,” calling Abby “a creative person without any roots or confidence to hold her together.” While the anxiety caused by that restless creative energy was “very recognizable,” Abby was too relentless. Dizzia was helped by what she had learned from Earle Gister about how to stop acting—“to stop thinking where the character was going to end up and to say to yourself, ‘I need to lose it here,’ and concentrate on the minutiae: ‘How do I feel when I’m saying this and when the other person says that back to me?’ Those little things will add up, and the moment will just happen and won’t have anything to do with you.”

The dream work provided a vital extra layer, finding images and associations in her subconscious that might be like Abby’s. “It helped me access those feelings in a more oblique way with images and sensations without having to narrativize them from my own life, like in substitution exercises,” she says.

Eventually it’s time to put the play up on its feet, but the preparations never stop. Still, Henderson says, “On the night you can’t be in your head. Anything that is valuable should now be in your pulse, in your bloodstream.”

To that end, final preparations are closer to athletic warmups than intellectual exercises. Keach does three or four minutes of vocal exercises before every performance “to get my jaw loose and limber and to get in touch with my emotional centers,” but he also does stretches for his hamstrings and his back. Feeling loose physically makes an actor relaxed and confident, he says, “and that’s the most important thing.”

Dizzia found a new warmup during Belleville, thanks to her Linklater voice teacher, Andrea Haring. “Without her I would have been mute,” Dizzia says. “She helped me to relax vocally so I could save my voice, and helped me find all the different ways Abby expressed her anxiety and fear and rage.” The key was that Haring made sure Dizzia focused on speaking as a physical act. While Abby is used to being up in her own head, cut off from her breath, as the play progresses she needs to be able to take a deep breath and feel her feet, to find the breathing needed to express herself to show that she can “be in her own body and see the truth of what is in front of her.”

Dizzia first encountered this favorite new exercise on a day when she was tired and run down. “Andrea had me stomp through the aisles of the theatre and repeat lines from the first scene,” she says. “It helped to see that your voice goes where your body does, and the more alive your body feels your voice will follow. I loved warming up near the [seats] instead of doing it onstage. It’s also nice to touch the chairs and know that someone will be there.”

Henderson points to one way that his training helped him prepare for his role as Turnbo in August Wilson’s Jitney, a role he played in numerous productions from 1996 through 2002 (Henderson was joined in the run, he points out, by “the great Anthony Chisholm,” Paul Butler, and Willis Burks). In the second act, Turnbo needs to deliver a load of exposition in the form of gossip, his character’s favorite pastime.

“One thing Juilliard really helped me with was understanding that long passages cannot be a speech—it has to be a joy for him to say, like a delicious meal,” he says, adding that the Meisner technique he learned from Bill Esper further refined that idea. “The other person is the most important person in the scene. So even though you’ve got all those sentences, you can’t just play the punctuation the way it looks on the page. You are looking at the other person for a reaction; you want what you are saying to have an effect on him.”

This means that the scene is not a matter of speaking for five minutes straight but of playing off the other person’s reactions, “even if it is just something in his eyes that says, ‘Go on now,’ or ‘Temper this here.’”

Those reactions are something an actor cannot prepare for, which makes that interaction crucial, even when words are not exchanged. “Acting is a craft, but acting with an ensemble raises it to an art form,” Henderson says.

Keach adds that there is another variable involved in the listening-and-reacting part of acting, and another important component for which an actor cannot truly prepare: the audience. A line may get big laughs one night and none the next, he says, but an actor must not waver. That’s when all the study, preparation, exercise, and expectation in the world must take second place to the primary truth of the actor’s calling. As Keach puts it simply: “You have to stay in character, in the moment of the play.”

Stuart Miller writes frequently for this magazine.

CRYSTAL DICKINSON

Hometown: Irvington, N.J.

Undergraduate: Seton Hall University

Graduate: University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign

Major credits: Seven Guitars, Two River Theater; Clybourne Park, Playwrights Horizons and Broadway; Broke-ology, Lincoln Center Theater

“My only acting in high school was in musicals, which I just did to make friends,” Dickinson says. “It was a posh school, so we had good production values, but we just watched the movie version of a show and copied it.”

Dickinson was an education major at Seton Hall, planning to become a kindergarten teacher, when she saw signs for The Colored Museum, the school’s first all-black show. The professor, Diedre Yates, not only cast Dickinson, she nurtured her career there and ultimately told her to drop her teaching plans. “She even coached me for the URTA audition on her personal time and drove me to it,” she says.

Yates got Dickinson started, but she still had a lot to learn when she got to graduate school. “Seton Hall only had a theatre in the round, so I didn’t even know what stage left and stage right were,” she says. “I was very raw.”

DANIEL DUQUE-ESTRADA

Hometown: Hayward, Calif.

Undergraduate: UC Berkeley

Graduate: Brown University

Major credits: Sense and Sensibility, Dallas Theater Center; Antony and Cleopatra, Shakespeare Dallas; The Happiest Song Plays Last, Oregon Shakespeare Festival

Duque-Estrada initially skipped college to become a writer. Eight years later, he was a bartender. He decided to go to community college. At Diablo Valley College, he saw signs about an audition for Macbeth. “For a long time I had thought Shakespeare was irrelevant until I read Hamlet while helping a friend prepare for a role,” Estrada recalls. Having acted in high school, he decided to give theatre another try, figuring community college was good “because I could fall flat on my face and there’d be nobody really watching.”

He auditioned with a soliloquy from Othello (“I rehearsed in Golden Gate Park screaming Iago into the wind”) and got the lead. “From there I didn’t look back.”

MARIA DIZZIA

Hometown: Cranford, N.J.

Undergraduate: Cornell University

Graduate: UC San Diego

Major credits: Drunken City, Playwrights Horizons; Belleville, New York Theatre Workshop (Drama Desk nomination); In the Next Room, Broadway (Tony nomination)

Dizzia spent the summer after third grade at the Westfield Summer Workshop under Jan Elby, doing acting, set design—a little of everything. One day in the parking lot she proclaimed to her mother, “I want to be an actor.”

But it took a little encouragement before Dizzia really believed it. At Cornell, acting teacher Alison Van Dyke had the most impact on Dizzia as a student advisor. “At that age, I was uncomfortable with the idea of becoming an actor,” Dizzia recalls. “The idea seemed so loaded and such a mystery, as if you were supposed to be born an actor.”

Van Dyke, however, always talked to Dizzia as one actor to another: “She would always say, ‘As an actor, Maria, you…’ She treated me like an artist and that meant so much to me.”

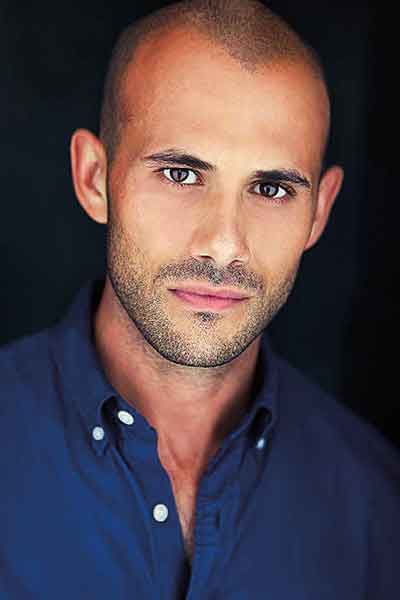

JON NORMAN SCHNEIDER

Hometown: The Bronx

Undergraduate: NYU Tisch School of the Arts

Graduate: University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign

Major credits: Tiger Style!, Alliance Theatre in Atlanta; Awake and Sing!, National Asian American Theatre Company* at the Public Theater; Edith Can Shoot Things and Hit Them, Actors Theatre of Louisville

Schneider was going to be a veterinarian. “I loved science and animals,” he says. But after a move to New Jersey as a teen, he caught the bug in high school choir. “I knew I had an affinity for performing,” he says.

There was nothing available nearby, so he persuaded his mother to let him take summer acting classes in New York. Schneider’s research led him to HB Studio, which had a class for teenagers, even those who were “totally green.”

“My second summer it crystallized that this was what I wanted to do,” he says. “What I learned there laid a foundation and had me hungry to find out more about the process.”

CARRIE COON

Hometown: Copley, Ohio

Undergraduate: University of Mount Union in Ohio

Graduate: University of Wisconsin–Madison

Major credits: Placebo, Playwrights Horizons; Three Sisters, Steppenwolf; Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, Steppenwolf and Broadway (Tony nomination)

Theatre wasn’t part of Coon’s life until one day, when, while waiting for soccer practice, she decided on a whim to try out for the high school play, Our Town. She wore shin guards to her audition and was cast as Emily.

“It was terrible but I had a great time,” Coon recalls. (Years later she made her professional debut as Emily.) An English major in college, she continued acting, though sports still came first. “My grandparents would pick me up at soccer practice and I would go into play rehearsal in my sweaty uniform,” she says.

Planning to study linguistics after college, Coon decided to give the URTA auditions a whirl. Her mother, aunt, and grandmother drove her to Chicago, and while they enjoyed “a vacation weekend with martinis,” Coon changed her life.

“Ignorance is bliss,” she says. “I saw other students doing exercises like blowing through their lips and stretching and all I thought was, ‘This seems really serious.’ Erica Daniels of Steppenwolf did my audition but I was not intimidated, because I didn’t know who she was.”

The University of Wisconsin–Madison welcomed Coon, though not with open arms. Professors later confessed that she was a “desperate last choice” to fill an empty slot. By far the youngest actor in her program, she learned more than just acting technique. “I was able to pay attention to myself during my early twenties—those desperate, damaging years—in a safe place where I could take risks.”

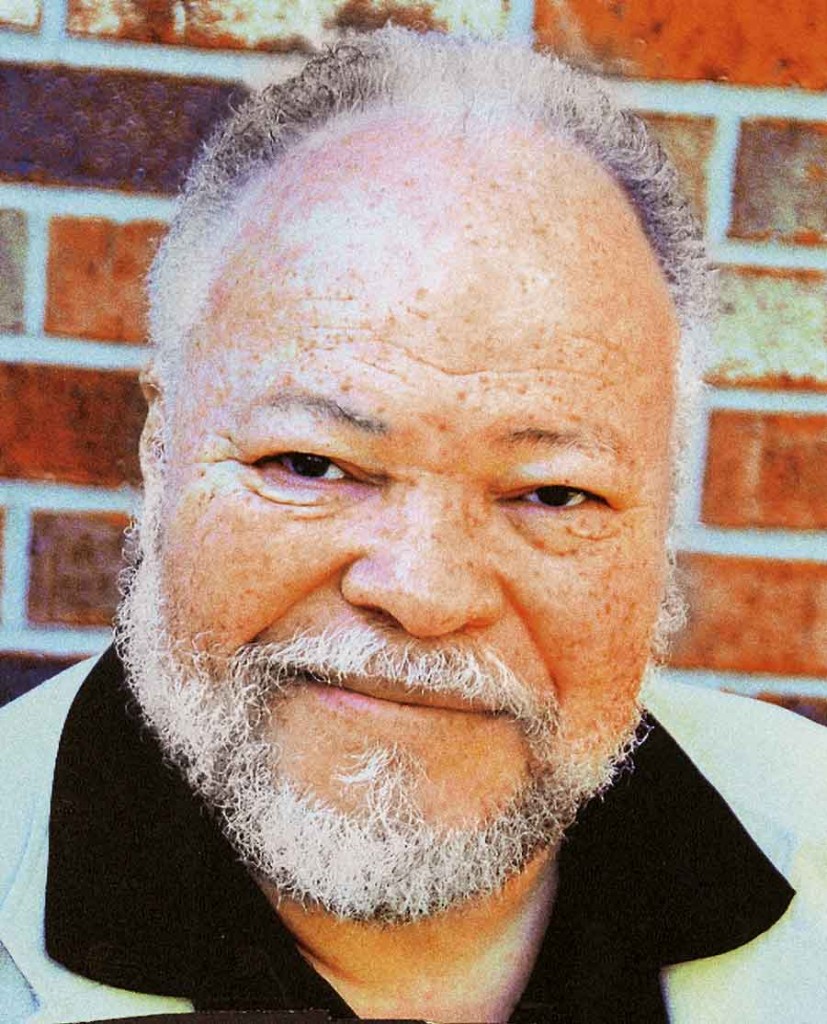

STEPHEN MCKINLEY HENDERSON

Hometowns: Kansas City, Mo., and Kansas City, Kan.

Undergraduate: Lincoln University, Juilliard School, North Carolina School of the Arts

Graduate: Purdue University

Major credits: Jitney, Pittsburgh Public Theater, Second Stage Theatre, Union Square Theatre (Obie and Drama Desk Awards for Ensemble Acting); Fences, Broadway (Tony nomination); Between Riverside and Crazy, Atlantic Theater, Second Stage (Obie Award and Lucille Lortel Award winner, Drama Desk nomination)

When Henderson was 7 and his older brother was 12, an aunt took them from church to church to raise money for Henderson’s brother to attend a school for the deaf. Henderson would recite Psalm 23 and the Lord’s Prayer while his brother signed it.

“I just was doing it by rote memorization when we practiced,” Henderson recalls, as was his brother. But in that first church, Henderson’s brother began signing with a passion. “I didn’t know it then, but he had what Stanislavski would call a super-objective. You could see it in his eyes.” Wanting it for his brother, Henderson found “that I couldn’t just say the prayers—I started performing them, too.”

Later, at segregated Sumner High, Henderson ecided to try acting. The drama teacher, Gloria Terrell, decided this light-skinned freshman should play Karl Lindner in A Raisin in the Sun. Henderson resisted, saying he’d be teased for playing a white man. “She said, ‘I know you—I’ve seen you in the neighborhood…you are cool. You’re the one who can handle it,’” Henderson says, then laughs. “She really did sell me a bill of goods.”

When Terrell was doing graduate studies at the University of Missouri, she imported Henderson, then a math major at the historically black Lincoln University, for a college production of Raisin, this time casting him as Walter Lee. The role got him spotted by John Houseman, who recruited Henderson for the first class of Juilliard.

“A professor at Lincoln said, ‘You’re the first student I’ve said this to, but you should leave. Go to New York. This is what you love.’’’

*A previous version of this article miscredited the producing theatre of Awake and Sing! It is the National Asian American Theatre Company, not Ma-Ya Theater Company.