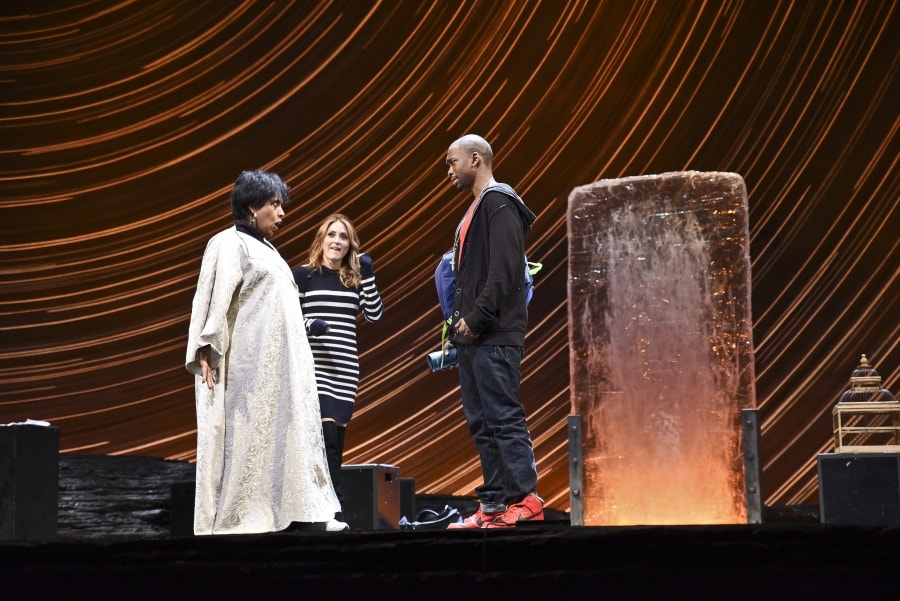

NEW YORK CITY: The 24 Hour Plays on Broadway kicked off with a meet-and-greet for performers, producers, directors, and writers. Celebrity stage actors, film stars, and legendary “Saturday Night Live” cast members—including some “repeat offenders” returning to the longstanding 24 Hour Company—sat in a circle at the American Airlines Theatre. The participants went around the room introducing themselves, presenting preposterous props and costume pieces, and sharing their special skills. Phylicia Rashad donned a fortune teller costume, complete with a fruit-filled headdress. Jason Biggs brought one broken ice skate he had found on the street. Kimonos, ukuleles, boxing gloves, and the sad remnants of a year-old Christmas tree topped the costume and props pile. Julia Stiles gave her best impression of her lookalike, martial arts star Ronda Rousey, and Jay Pharoah delivered an operatic rendition of Imogen Heap’s “Hide and Seek.”

This was more than just a fun way to spend a Sunday evening. The late-night gathering was the first work session of the now-standard process of the quick plays, intended to inspire an assemblage of celebrity playwrights to write six 8- to 10-minute plays that would go up on that very stage—in less than 24 hours.

This expedited creative chaos, however terrifying it may be, particularly for first-time participants, is by now a tried-and-true formula. The 24 Hour Play Company has been mounting events like these since 1995, and doing a celebrity gala version on Broadway since 2001. The company began when a group of friends on the Lower East Side wanted to make theatre but were short on time, money, and space. But Tina Fallon, the founding ringleader of the group, saw a way to turn the troupe’s lack of resources into an asset. She says she was inspired by Scott McCloud, a comic artist who challenged fellow comic book writers to spawn full-fledged drawings and stories in just one day. Fellow producers Lindsay Bowen and Kurt Gardner hopped on board.

Of course, the idea of ephemeral theatre made quickly is not a new concept. But the 24 Hour Company has turned it into an art. “It is miraculous on the most granular level,” effused Fallon. “And to have something that is so joyous be available to so many people–why else would you make art?”

In the company’s meager beginnings, the friends produced plays one after another, pumping out shows, merchandise, and luring crowds with beer. Bowen described that time as the company’s “Muppet Show phase.” Fallon recalled bringing the model to the first New York International Fringe Festival in 1997, where they produced productions back-to-back for a total of 240 hours. “It was hard to do it that much, but that moment was a real coming out for us as an event,” Fallon said. “We knew we were going to be able to attract enough talent.”

Indeed, while time and money will always be lacking for the plays, the company is never hard up for talent. “How is it possible that that concentration of talent is together onstage?” Fallon continues to marvel each year.

The company’s first play in 1995 happened also to be playwright Will Eno’s first play. Since then, the process has been a great way for writers to try their hand at writing for the stage, and for actors who want to get their feet wet; Chris Rock, for one, appeared in the plays before making his Broadway debut in The Motherfucker with the Hat in 2011.

Now, 20 years later, the plays have been produced in 10 countries, and the company licenses the concept, as well as how-to guides, to universities and community theatres. Fallon and company also travel around the world to help theatres produce their own plays in less than 24 hours.

The international forays have helped to inform the development process of the plays, and cultural nuances help to create new experiences. The 24 Hour Plays in Dublin, for instance, yielded more dramatic plays than in the U.S., and in Athens, Greece, theatre artists relied more heavily on stock characters.

“The goal is the same, but the manner in which people get to that point can vary quite a lot,” said producer Philip Naudé, who leads the international component of the company.

The plays haven’t only pointed up cultural differences; they’ve also brought people together in times of conflict. The first celebrity gala on Broadway, in fact, occurred just two weeks after 9/11. The 24 Hour Plays event in 2005 at the Old Vic in London, organized by its artistic director, Kevin Spacey, took place a week after the 7/7 bombings. In 2004, riots and street demonstrations disrupted the development process for the plays in Athens. And the most recent staging on Broadway happened to take the stage in the wake of the terrorist attacks in Paris.

“It is an opportunity to come together as a community and have a good, cathartic experience together at the theatre,” said Fallon. “I genuinely believe in the power of catharsis now—it doesn’t necessarily make its way into the content of the plays. There is just something about coming together and doing something.”

Though the company is now a global franchise, the initial group of friends and founders are still heavily involved, alongside several cohorts of volunteers who dedicate their time to help make the productions work. The company has also annexed a collective of producers, as Fallon puts it, to help mount the shows around the world. The core team is now made up of Fallon, Bowen, Gardner, Naudé, Mark Armstrong, Kelcie Beene, Sarah Bisman Storm, and Lou Moreno.

But after all these years, the concept has not changed, nor have the day-to-day operations of the 24 Hour Company. It still runs without office space or a phone number, and generates all income from licensing and production fees. Bowen said the company didn’t feel great about asking actors in the 1990s to donate their time while the organizers received a paycheck—so they never did, and they still don’t.

The company’s primary business model is the celebrity gala; it’s annual Broadway event helps raise funds for arts education programs such as the Urban Arts Partnership in New York City. “If you are raising money for charity, everybody gets on board,” said Fallon.

By Monday morning, and the American Airlines Theatre was filled with the many people who’d climbedon board. Jesse Eisenberg, who couldn’t participate in the performance, showed up unannounced to unload a beer truck for the theatre’s concessions and stuff programs. Actors were scattered around the lobby learning lines, practicing blocking, and anxiously awaiting their first and last tech rehearsal before the show.

“Our big fear 15 years ago was that this thing would just be a fad—that it would just have its lifespan and then go away,” said Bowen. “I feel like now we can finally say that it is not going away!” he said, as repeat offender Rachel Dratch walked by and excitedly waved.

The theatre buzzed with the excitement of a high school theatre cast, where the opening night jitters are fused with the bittersweet sorrows of closing night. That energy that also fills the audience.

“You have your opening night audience, your closing night audience, and none of that middle of the run when nobody comes,” quipped Fallon.

The energetic audience is a comfort to the writers, as the audience doesn’t expect the work to be polished or finely honed.

David Lindsay-Abaire, a repeat offender of 13 years, contributed another overnight play this year. He said he even managed to fit in a nap and a basketball game with his son before returning to the theatre. “I’ve done this before, I know what to expect, and I know how it goes,” he said. “That is all there, and that is reassuring, but the terror never goes away—that is always fresh and new.”

Lindsay-Abaire, like many of the playwrights this year, took inspiration from the set for Old Times currently running at the American Airlines Theatre, where a spiraling vortex wall and ice sculpture take center stage. “I embraced the set—there was no way around that set and the giant ice sculpture,” he said with a laugh.

In his years of doing the plays, Lindsay-Abaire’s most memorable mishap was when one of the actors went up on a line, and each of the actors onstage thought it was the other person’s line. “From the audience, I yelled out the line, and got the biggest laugh of the night!” said Lindsay-Abaire.

That’s the spirit of the event. The six plays on this year, penned by Lindsay-Abaire, Jonathan Marc Sherman, Lucy Thurber, Rachel Axler, David Cross, and Dipika Guha, all included elements from the Sunday night meet-and-greet. Pharoah got to show off his operatic range, Stiles proudly portrayed Rousey, and Vanessa Williams portrayed a rough-and-tumble character, per her request.

Ticket prices for this year’s charity performance started at $500, and 750 people attended raising nearly $650,000 for the Urban Arts Partnership.

The whirlwind experience, which Cross described as “daunting, gratifying, and exhausting,” concluded with an epic after-party featuring DJ QuestLove. “What could be better?” said Fallon. “It’s everything I love about theatre, and none of the things that are soul-crushing. It also helps to have QuestLove as your DJ—you just can’t stop dancing!”

What’s next? The company is branching, with musicals taking the stage in the spring and its Nationals program going up in the summer. When looking back at the company’s two-decade history, Fallon and Bowen are most grateful for the working relationships that the company have fostered.

Fallon described the 20th anniversary year as “the year of Mark Armstrong,” referring to the company’s first paid staffer, who is now taking the reins as executive director to tackle the day-to-day organizational tasks of running the company. Armstrong’s job, in Fallon’s view, is to take the 24 Hour Company S.W.A.T. team and turn it into a police force.

Armstrong has been involved with the company for the past 12 years in varying leadership capacities and as a director. He also spearheaded the publication of The 24 Hour Plays Anthology.

“One of my challenges is diversifying revenue streams, so that we are not subsisting on the income from one big show,” says Armstrong. Accordingly, the company is lining up partnerships around the globe, and will be moving into its first in-kind office space at the New School this month (with an actual phone number!).

Armstrong’s goal, he said, is to stabilize and grow the organization so that it can continue for future generations, just as it had been a great support system and creative resource for him as a young theatremaker. One way the company is fulfilling that mission is through the Nationals program, which brings together theatremakers 25 and under to the New School to create plays with the 24 Hour Company. Kelcie Beene, now a producing member of the company, got her start in the Nationals program. Steve Wody, a 2014 Nationals acting participant, appeared alongside Edie Falco in this year’s Broadway performance.

“The process wins and everybody is able to do it—students do it the same way we are do it for celebrity galas—-the cycle is the same,” said Fallon.

The company has come a long way from the Lower East Side, and so have its founders: Fallon fills her time as a real estate agent, Bowen is now an entertainment lawyer, and Gardner works as a union stagehand. What spare time they do have is dedicated to their passion project.

“I am able to walk away from a lot of the day-to-day operations of the company, and focus on becoming more of an advisory role and letting the next generation of new artists, which includes new producers, rise up through the ranks and run the show,” said Fallon. “That’s what needs to happening in the American theatre, and it starts at home.”

Correction: An earlier version stated that Rainn Wilson and Aasif Mandvi appeared in Will Eno’s first play at the first iteration of the 24 Hour Company’s plays. Wilson directed and Mandvi performed in early productions of the 24 Hour Company, but neither participated in the inaugural production.